[do_widget id=search-2]

Interview: James Mary O’Connor FAIA (Winter 2017)

Playing the China Card: The MRY Example

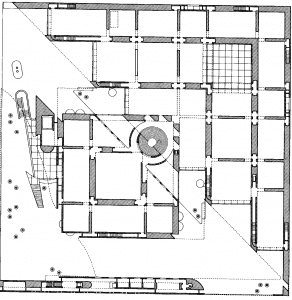

Chun Sen Bi An Housing, Chongqing (competition 2004; completion 2010)

COMPETITIONS: Moore Ruble Yudell (MRY) has had a reputation as an international player since the 1980s. How did you manage to become involved in China?

James O’Connor: We were first invited to take part in a (developer) competition in Beijing in 2002, the Beijing Century Center. We won, but the project was never built. The client was not that serious, and we never got paid. After that, we said that we would never enter another competition in China. But, what turned out to be a real clientele kept after us to participate in one of their projects. After turning them down several times, we finally relented. That was a competition for the Tianjin Xin-he New Town Master Plan and Housing in Tianjin—which we did win.

Chun Sen Bi An perspectives (above)

Chun Sen Bi An Housing Master Plan

COMPETITIONS: Once you have become established in China, it would seem that you almost can pick and choose between competitions and projects.

O’Connor: Right before the time of the Olympics, there were few foreign firms working there so we were interviewing clients as opposed to clients interviewing us. And every time we would go out, we would be involved with another project, or another competition. It all started in kind of a shaky way; but that’s kind of how it evolved.

Interview: William Pedersen FAIA (Winter 1996/97)

333 Wacker Drive - view with Chicago River in foreground (photo: ©Barbara Karant)

COMPETITIONS: When you are called on to design a ‘foreground’ building for a corporate client—although it’s usually an office building, it could be any number of building types—how do you balance the private and public interest beyond the usual zoning regulations?

left and below

Gargoyle Club Prize

Best Architectural Thesis, University of Minnesota School of Architecture (1961)

Theme: Hospital Project

Images: courtesy William Pedersen

Pedersen: The interest of the client as it relates to the quantity of the construction they wish to place on a site is perhaps the most difficult issue, particularly during the 80s, when a tremendous amount of construction was taking place in the United States, and one more office building was not hailed by anybody as a contribution to society. The situation has changed rather dramatically in the 90s, when almost none of them are being built; so the issue is not as pressing. But there always is the question, ‘Is a building, given the bulk proposed, appropriate for its specific condition?’ One’s ability to deal with that issue is somewhat limited because zoning establishes what is of right, and not of right. Therefore, the battle has largely been fought prior to our entrance on the scene.

Past that point, the relationship of our buildings to a specific context has been a fundamental issue of our architecture. This is particularly how we take tall buildings, which are in themselves somewhat insular, autonomous and discrete, and bring them into a more social state of existence. That’s been the subject of our study for the last twenty years. We’ve developed strategies for doing that, of which I’ve spoken at length. The preoccupation of making the tall buildings—part of a more continuous, overriding fabric—that’s been central to our architecture.

COMPETITIONS: The most obvious argument against contextualism—as many people understand it—would be the Pompidou Centre in Paris, which has turned out to be the most visitied and popular building in that city. Wouldn’t that seem to give architects a good argument for doing something different? Was that even a lesson?

WP: Juxtaposition is a fundamental contextual strategy; but it has to be used sparingly and has to be introduced at exactly the right moment for it to have a powerful effect. For example, the Seagrams Building on Park Avenue—before any of the other buildings followed suit—was exceedingly powerful and very successful as a result of the juxtaposition at that particular place. I would argue that our building in Chicago (333 Wacker Drive) is an equally successful contextual building. It’s on the only triangular site of the Chicago grid at a bend in the Chicago River, and it sits within a context of totally masonry buildings, largely of the classical derivation. Somehow the relationship between those very distinct parts works. We were asked to build a building right next to 333 Wacker Drive, which did not occupy a unique geometric piece of property, but in fact became more of a continuation of the street wall leading up to 333 Wacker. We elected there to utilize a more Classical language in total juxtaposition to our own 333 Wacker in an effort to try to achieve the continuity of the wall that we thought was necessary, but also to maintain that poignancy of a juxtaposition to 333 Wacker Drive to the rest of the context. It would weaken it tremendously if it had been reproduced next door.

The same is true of the Pompidou Centre. If one were to tear down that section of Paris around it and build a number of Pompidou Centers there, it would lose its impact, because ifs impact is an object set within a very careful framing in that traditional neighborhood. Without the dialogue between the two, the game is over.

AAL Hqs. building addition (1971), Appleton, Wisconsin

COMPETITIONS: Most people seem to believe that 333 Wacker is the best building you have done. Maybe it was the time and unique site. It was one of those projects where one announces, ‘Well, here I am.’ Sometimes it’s difficult to top a wonderful building like that, though you may believe your next building is the one you like best.

WP: I think that 333 was a product of my sensibility at that point in time. It was a building that tended tobe an intuitive response to the site. In terms of it language, it came out of a couple of other buildings I had done immediately prior to that—one being the Aid Association for Lutherans in Appleton, Wisconsin, the other being the Brooklyn Criminal Courts Building, which had very similar geometric ideas in terms of its relationship to context. The very conscious attitude of trying to make the tall building part of a larger urban contet preoccupied us for the next five years. As a result, we used a more classical language to try to develop connecting strategies, because a Classical language is largely built on ideas of connection of pieces and parts, one to another…buildings connect well because they have parts that are combined and are part of a central language.

Interview: Axel Schultes (Spring 1997)

with Stanley Collyer

Bundeskanzleramt Berlin Competition (1996); Completion (2000) Photo: courtesy Schultes Frank Architekten

COMPETITIONS: In our last conversation, we talked about the whole issue of Berlin's identity and what approach one should use in reconstructing the urban fabric between East and West—where the wall used to be.

Axel Schultes: Maybe I learned something during a recent lecture I gave in Palermo (Italy). Afterwards, some German specialists in philosophy and German thinking—brilliant people, I must say—came up to me and said, 'What you said about Berlin and what you are doing there with the Federal Chancellery (Bundeskanzleiamt), for us is what Ernst Bloch and Walter Benjamin talked about, especially when they looked at Italy and the cities in Italy. We noticed immediately in your work that (same) issue of porosity.' Both used this term: Benjamin wrote a small article on Naples, and Bloch wrote about Italy as a whole.

We always had a tendency to avoid the term, 'transparency.' Transparency is usually the use of glass to make buildings less alienating to someone outside. But for us, glass is no material to create spaces; so transparency as we see it is depths of spaces or layering. Porosity is something much more precise—what we strive for. We wanted the same effect in Friedrichstrasse (Interior Mall): it should not be this close-up thing of the Galeries Lafayette (Jean Nouvel) or Ungers, where you only have some holes in it. Porosity for us is like a sponge—to enable a building to fill up with life, to turn a private space into a public one by penetrating it with a public space. The old buildings in Berlin are examples of this, with two, three, sometimes even four interior public spaces.

Berlin Baumschulenweg Crematory (1993)

COMPETITIONS: You are referring to the interior courtyards (Hinterhöfe)?

AS: Yes. Nothing of this sort exists anymore in Berlin. Most buildings (at the street) are flat, sometimes elegant, sometime ugly. The Galeries Lafayette, with all its glass, is as closed (to the outside) as one of Unger's sandstone buildings. It's the same issue in the construction of every building. Take, for instance, the Berlin Schloss (the palace in the center of Berlin), which was completely demolished after WWII, and which some people think should be resurrected. This has been on our mind constantly.*

It would be such a contrast to urbanism—needing to punch holes in it to get inside—open to all the people and all walks of life. I can give many examples of this, for me very northern, very restrained, very alien to everything which infuses a culture with life. All the people here like Kohlhof, Ungers, Kleihues, etc.; all have that tendency of closing. Even Libeskind—and maybe he doesn't think about it or want to have it appear in such a manner—does it with the Jewish Museum where there is no penetration. There is always this hiding, this animosity to the urban fabric. They are not interested in breaking it up.

Interview: James Stirling (Spring 1993) with Jorge Glusberg

Nara Convention Center Jurors James Stirling with Jorge Glusberg (right)

GLUSBERG: What do you feel are the basic components necessary for good design?

STIRLING: I think every building must have at least two good ideas. I don’t see the design process as a sudden blinding flash of insight. That might be true for a structure that has one main purpose, like a stadium or an office building; but, in my opinion, it won’t work with a multi-functional building. That, in fact, is what most of the projects in our office tend to be.

GLUSBERG: Then how would you describe your process?

STIRLING: We really try to be careful and conscientious in our analysis. We work in a very linear fashion so that the final design reflects the path of decision-making.

GLUSBERG: You just said that few of your buildings have a simple program: but what about the Science Center in Berlin?

Berlin Science Center (photos: Stanley Collyer)

STIRLING: Yes, you’re right. That is an office complex, but it also incorporates an existing Beaux Arts building that was remodeled into several lecture halls. In the office building we had to provide three hundred similar offices for researchers. We were looking for an architectural solution, rather than for a solution to the program which would have been very repetitive. So we created a group of five adjoining buildings surrounding a courtyard. The space between the administration, the sociology and the environment departments, the library, and the archive helped us to overcome the monotony of the program.

Interview: Arthur Erickson (Fall 1997)

Cover of the 1997 Fall issue of COMPETITIONS (left), showing the phase one completion of Erickson's University of British Columbia Library. Photo: Stanley Collyer

Vancouver Civic Center/Robson Squre (right) Photo: courtesy Arthur Erickson

Interview: Ralph Johnson of Perkins+Will (Fall 1995)

COMPETITIONS: you have been in both open and invited compe-titions—both as a juror and as a participant. Which type do you prefer and why?

RALPH JOHNSON: I think both are viable. For a young architect, open competitions are great, because they are not going to get invited. It’s a way for young architects to break into a bigger scope of work. It’s an oppor-tunity for someone who doesn’t have the experience in that particular building type to get into a new area.

Shanghai Natural History Museum Photos: courtesy Perkins and Will

An invited competition usually involves some kind of portfolio or resume of the firm’s work, and you usually get selected on experience in that particular building type. In the latter case, you are probably dealing with fairly extensive presentation requirements and a big outlay of money. It often also involves a couple of stages. If the compensation is adequate, which is usually six figures—$100,000-$200,000—it’s great. Most of the time, it’s inadequate. For the recent (Beirut Conference Center) competition, we did in Lebanon, it was $200,000, and that was enough to cover (our) costs. So there are benefits for both types of competitions.

COMPETITIONS: And as a panelist?

RJ: It’s much more difficult to jury the open ones because it takes longer. I was on the Astronaut Memorial jury, and there were over 600 entries. You normally don’t interview the architect; it’s single-stage. It’s more a process of winnowing out inadequate submissions—which is easy to do—and getting down to the ten percent after the first cut. In the case of an invited competition, you have five to ten submissions from very qualified firms. I think it’s good if you can actually interview firms and have a question and answer period. In an open competition, it’s almost inevitable that you wonder who is actually doing the project, how qualified the architect is. It’s hard to keep that out of your mind.

Shanghai Natural History Museum Photos: courtesy Perkins and Will

COMPETITIONS: In other words, the presentation isn’t necessarily an indication of the qualifications of the designer?

RJ: I wasn’t on the jury in the case of the Vietnam Memorial, which was a famous competition. There were very sketchy charcoal drawings (by Maya Lin), which really didn’t indicate anything other than conceptual design capabilities. How could you possibly come to any conclusion of technical competence based on those drawings? You really have to read into it and assume a lot in terms of the person. In that case, of course, it was a great success as a non-complex building type. As a laboratory or something else, it’s a different story.

COMPETITIONS: There are a number of anecdotes concerning jurors speculating about the author behind a competition entry—the one in Paris resulting in the Grand Arch is an example. Richard Rogers, a competition juror, supposedly remarked to another juror, Richard Meier, that the author of what eventually turned out to be the winning design, “might be a nobody.” Meier reminded Rogers that, before Pompidou, he was a “nobody.”

Interview: Joe Valerio (Fall 2004)

COMPETITIONS: As has been case with many architects, your career got a very big boost by virtue of winning a competition — Colton Palms Senior Apartments. Was that the very first competition you participated in?

VALERIO: No. It wasn’t the first, and it wasn’t the last. It was interesting in that we won, and also won a PA Design Award for it and an AIA Honor Award for the project when it was finished. It covered the gamut of awards that one could win with a project. And it got built almost exactly the way it was designed for the competition.

COMPETITIONS: Was the competition open or invited?

VALERIO: It was open, and there were about 140 entries from around the world. There were five finalists in the 2-stage competition, and we were selected at the end of the second stage.

COMPETITIONS: Do you recall who ran that competition?

VALERIO: Michael Pittas, who did a very commendable job. The two key jurors were Rob Quigley and Don Lyndon. In hindsight, it was one of those things where all the stars were alligned and there was a very dynamic city manager (Frank Benest). This was his first job as city manager. He went on to become city manager in Brea, California, a wealthier suburb. Now he is city manager of Palo Alto. He recently said to me that one thing he was always trying to get communities to do was to invest in their downtowns. ‘Here in Palo Alto, nobody wants any more investment in downtown.’ Frank was very innovative, in that he used the competition process to get something to happen that probably could not have happened any other way. California in the early 90s had a law which said that, ‘if you set up a redevelopment district, you could capture the increase in real estate tax revenue in that district and use it to help finance the development.

So it was a kind of bootstrap sort of approach called tiff financing, which is very popular all over the U.S., including in Chicago. You have to set aside 20% from that funding mechanism for

affordable housing. So everybody set up these greenbelt districts and this set-aside fund. But nobody wanted affordable housing, because affordable housing equated with subsidized housing. It didn’t matter that the people that really wanted to use the affordable housing were seniors from the community who didn’t want to leave, or policemen or firemen who couldn’t afford to live in communities they were serving. People were just against affordable housing.

Colton Palms Apartments (Competition winner 1988) Colton Palms, California

Photo: courtesy Valerio Dewalt Train

Colton Palms Apartments (Competition winner 1988) Colton Palms, California

So Frank came up with the idea, if he could create enough buzz about the project and really make it into this event, he could get the city to build affordable housing projects. It turned out that they had an abandoned grocery store in their old downtown area, which covered most of a city block. The city had taken control of the property. So he had the money and the set-aside. He had this piece of property which had to be redeveloped; but he couldn’t get the city to just do it. So he came up with this idea of doing a competition, hired Michael Pittas to organize it, and it worked. There was all this publicity and notoriety; this competition was like a city festival. It was a very public event where people showed up for the presentations. So not only was it an architectural event; but it had a real social underpinning that was really admirable. Without that mechanism, I doubt if Frank would have been successful.

COMPETITIONS: In retrospect, would you have any clues as to why you won?

Interview: Will Alsop (Winter 2002)

with George Kapelos

Swansea Literature Center (competition 1993)

KAPELOS: What led you to architecture?

ALSOP: I want to start by saying that I never remember not wanting to be an architect. Why that should be I have no idea. I grew up in England in Northampton near a Peter Behrens house. It was one of the first modern movement houses in the UK, built around 1926 and it had an interior done by Charles Rennie Mackintosh. As a child you were always aware of this house. My parents had different views on this house. My mother thought it was incredibly ugly, while my father, who was 64 when I was born, hated Victorian architecture. Their views influenced me. I got to like the house—I even found it fascinating—it was comfortable and I responded to its ambiance. Plus it had extraordinary furnishings, so I guess this is where I started.

KAPELOS: What were your earliest experiences with architecture?

ALSOP: My father died when I was quite young—I was 15—and I went to work for a local architectural firm. This office was not what I considered to be ‘architecture.’ I measured buildings and did rudimentary working drawings. The practice was disappointing. One of the partners, Brian Pennock, thought of the design process as first getting the plan right and then designing the building’s elevations. It struck me curious that you wouldn’t think of the building as a whole. The plan and the object were one, in my thinking. Pennock was trained along the lines of ‘form follows function.’ In this line of thinking everything would come from the plan. Pennock, in my opinion, was deliberately obscuring his sensibility. I have been suspicious of this or any methodology ever since. You can teach people to build, but ‘architecture’ is something else. That’s what I want to be paid for. The something else, that’s where you put the most value.

Second Place, Centre Georges Pompidou competition (1971)

KAPELOS: What about your early exposure to art and sculpture?

Interview: Cesar Pelli (Summer1995)

Miami Performing Arts Center with Sears Tower in center; Competition (1995), Completion (2006)

COMPETITIONS: What was the first competition you participated in?

PELLI: I believe the first was during my third year in school as an undergraduate. It was a sketch competition for completed designs. It was run by Ernesto Rogers, an Italian architect (an uncle of Richard Rogers), who was teaching in Tucumán. I won it, and, as the first prize, he gave me Space, Time and Architecture, a book that I still have.

Petronis Towers (1992-1996) Photos and images courtesy Cesar Pelli Associates/Pelli Clarke Pelli

COMPETITIONS: There have recently been design competitions, which consist only of sketches. For instance, there was a sketch competition for the Getty, won by Machado and Silvetti. How do you feel about this kind of competition, which requires less work than a normal design competition?

PELLI: It depends how you look at it. In terms of effort and investment in time, money and energy, it’s very fair. The problem with a sketch competition is that it tends to exaggerate the problems of architectural competitions, particularly when architects judge them. What is being chosen is an image. Buildings are much, much more than images. Buildings have to fit a place, have to fit a function, have to be built within a certain budget. The sketch may be wonderful and lovely, but one may end up with the wrong building. I would never advise a client that is trying to select an architect to organize a sketch competition.

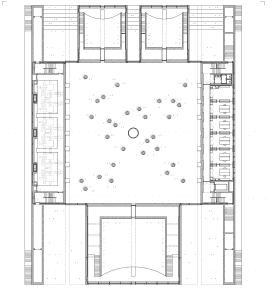

San Francisco Transbay Terminal- aerial view (left); upper level park view (above) – Images courtesy Pelli Clarke Pelli

San Francisco Transbay Terminal- Images courtesy Pelli Clarke Pelli

San Francisco Transbay Terminal – Competition (2007) Completion, Phase I (2017) Images courtesy Pelli Clarke Pelli

COMPETITIONS: Going back to your first competitions….

PELLI: The first competition I did after I came to the states was the Crane Competition…the firm that makes sinks for bathrooms, etc. I did not win first prize, but I won a second or third prize—$100. The subject was ‘a bathroom.’ Of course I have participated in many competitions since then. With some I have problems; but I enjoy the act of designing and competing.

COMPETITIONS: This ‘bathroom competition’ brings up the subject of how young architects gain access to the next level. Aren’t smaller competitions like this possibly the way for young architects to advance their careers?

Interview: Weiss Manfredi Architects (Spring 2003)

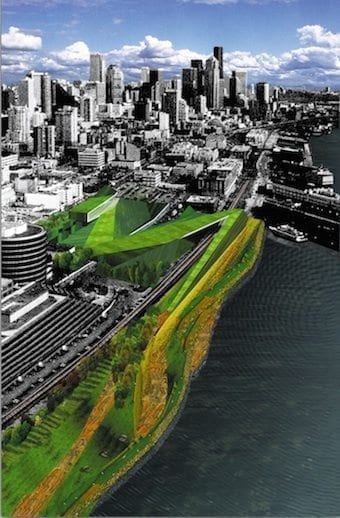

Seattle Olympia Park Sculpture Gardens – opening day (photo: Ben Benschneider)

COMPETITIONS: What were the main program challenges you had to solve in designing the Seattle Sculpture Park? The project is now in the development phase (2003); so has your approach changed somewhat, or are you sticking pretty much to your original plan?

WEISS: We invested an enormous amount of time exploring a number of strategies. We ultimately focused on a strategy of inventing an entirely new topography, wandering from the city to the water’s edge, over highway and train tracks. That proved to be a rather supple strategy. In fact, the current design right now is very much an elaboration of that scheme, but with a more richly developed palate, with landscape, urban, infra- structural, architectural, artistic agendas shaping it.

MANFREDI: The scheme was resilient enough, partially because the proposition of building a sculpture park in an urban setting had no models that we could fall back on. So we did look at a very large range of ways to envision the site. We talked to many artists and sculptors about what would constitute an interesting and dynamic sculpture park. A lot of adjustments went on prior to legally receiving the contract. But the scheme was ultimately able to undergo change without being radically different.

Original schematic proposal: Olympia Park Sculpture Gardens

WEISS: The strategy itself is incredibly simple on one level. The strategy can be drawn with one hand. That kind of clarity on one level has been able to accommodate a number of adjustments and change—the just right 20’6” clearance for the federal highway, the 23’6” clearance over the train tracks , etc; very approximate assumptions become more definite in development.

COMPETITIONS: To what extent do you want to be intrusive in designing this Seattle landscape, and to what extent do you want the sculpture in the landscape to do the talking?

MANFREDI: The thing about this site is that there is nothing natural there. It is actually a brownfield site, which has been excavated. What fascinates us is the opportunity to rethink what an artificial landscape might be; we don’t have the usual split between what is natural and what is artificial. This is all an artificial landscape within a very interesting city with topography, train tracks, a shoreline with boats—this is about as artificial as you can get. Everything is invented; so that kind of schism isn’t present on this site.

WEISS: In this case, one has to think of the landscape as a kind of partner for art. Here the surrounding itself is so much larger than the site with the views to the south of the city and the views to the north of the water and mountains. The site feels as large as the sound or as large as the city. We create a brand new topography, which navigates that forty-foot drop from the city to the water’s edge. If it were just a flat landscape, it would be a pretty uninteresting setting for art. So we have hyper-articulated the ups and the downs within certain areas, whereas the primary armature is very gentle over a slow path. If anything, we wanted to heighten the understanding of where it is highly topographically charged, and where it is neutral. So really it is both.

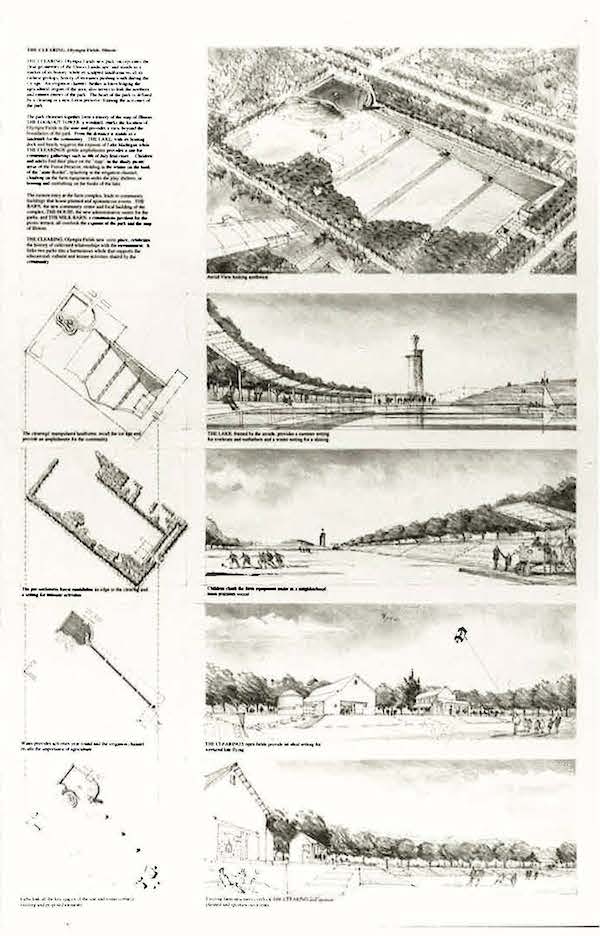

COMPETITIONS: The Olympia Fields Park competition was undoubtedly a milestone event, which opened a lot of doors for you. What prepared you for winning that competition?

MANFREDI: This sounds like a glib answer, but I think that a little naiveté helped. We always enter a competition with a little bit of innocence and a very high degree of optimism. Those are some of the virtues that still sustain us as we take on other competitions. If you have an optimistic frame of mind, you can be freer to propose solutions that you otherwise might be concerned about, given the program, site, or jury. You have to be somewhat fearless about that and have a certain amount of optimism and innocence.

WEISS: We actually initiated our practice by collaborating on a couple of pro bono projects in Harlem—one for a school community center, the other for low-income housing. I think what drew us together initially as architects was the conviction that architecture should be taking place in the public realm, where funding is so often elusive.

What prepared us to win may be harder to answer than what prepared us to enter

(Olympia Fields). What made that interesting was that it was asking how to create a center or a ‘there, there’ in an undifferentiated suburban landscape, a realm that didn’t have a common ground. The Olympia Fields project was clearly one which had a strategic budget. But they had very real resources to realize the client’s aspirations—to create a center where there had not been one for the community. It was interesting because it involved architecture and landscape; engineering and art.

MANFREDI: When you enter a competition, it has to ask the kind of question that is inherently fascinating. The competition for Olympia Fields asked not only social and formal questions, but posited the opportunity to explore a whole range of disciplines that are often segregated—like landscape architecture and ecology, architecture and civil engineering.

COMPETITIONS: The Olympia Fields site was very compact for a park. The space between the buildings on one end and the beginning of the terraced activities areas is separated by a depression in the landscape which leaves the viewer with the impression of the space being larger than it actually is. This is an old trick employed by landscape architects. Since you are both architects, not landscape architects; I wondered if this was a calculated gesture on your part?

The American Green – Olympia Fields Mitchell Park Competition board (courtesy: Weiss Manfredi Architects)

View to Mitchell Park entrance with meeting facilities (left) and administrative offices (right) Photo: Paul Warchol

WEISS: That touches on the observation that Michael made earlier about our frustration with these disciplinary boundaries—they’re really just administrative boundaries. Who is to say that a landscape architect might not have profound views about making architecture? Similarly, why shouldn’t an architect have views about what it takes to make a setting for architecture? Our background is such that we grew up in environments where the landscape was in many ways formative to our understanding of what we loved about architecture—Michael came from Italy, Rome to be precise; I grew up in northern California, in the apricot orchard district in the hills. In all cases the architecture was a participant, in a much larger landscape or setting, but never the sole presence. All of those have been about shaping settings as well as shaping buildings. You can say that it is the purview of the landscape architect in the traditional sense; but arguably, I think we have been keen on straddling a whole series of disciplines.