After receiving his Diploma in Architecture from the Dublin Institute of Technology and BS in Architecture from Trinity College in Dublin, James received his Masters in Architecture from the University of California, Los Angeles while a Fulbright Scholar in the U.S. Shortly after his time as a student in Charles Moore’s Master Class at UCLA, he joined the Moore firm in Los Angeles, now Moore Ruble Yudell. Beginning in the late 1980s, he was involved in the firm’s many projects in Germany, many of which dealt with masterplanning and the construction of large housing, primarily in Berlin. Subsequently, he was involved in the Potatisåkern Master Plan & Housing, as well as the Bo01 Housing Exhibition, both in Malmö, Sweden.

James was MRY’s point person in its subsequent involvement with the firm’s many projects in the People’s Republic of China, beginning with their winning competition proposal for the Century Center project in Beijing. Although unbuilt, it didn’t escape the notice of the Chinese, who invited the firm to participate in a competition for the Tianjin Xin-He large neighborhood masterplan—which they won. This was followed by the 2004 Chun Sen Bi An Housing Masterplan competition in the city of Chongqing, located in central China—completed in 2010. This high profile project resulted in a number of affordable and high-end housing projects throughout China. The firm’s most remarkable sustainability project was the COFCO Agricultural Eco-Valley Master Plan project outside Beijing, envisioned to become the first net zero-carbon project of its kind in the world.

In the meantime, the firm’s focus in China has evolved from its concentration on housing to institutional projects, such as the Shanghai University of Technology‘s research buildings. In the meantime MRY has been noted as a leader in the design of campus projects in the U.S. and abroad, as well as numerous government projects—courthouses and embassies.

Playing the China Card: The MRY Example

Chun Sen Bi An Housing, Chongqing (competition 2004; completion 2010)

COMPETITIONS: Moore Ruble Yudell (MRY) has had a reputation as an international player since the 1980s. How did you manage to become involved in China?

James O’Connor: We were first invited to take part in a (developer) competition in Beijing in 2002, the Beijing Century Center. We won, but the project was never built. The client was not that serious, and we never got paid. After that, we said that we would never enter another competition in China. But, what turned out to be a real clientele kept after us to participate in one of their projects. After turning them down several times, we finally relented. That was a competition for the Tianjin Xin-he New Town Master Plan and Housing in Tianjin—which we did win.

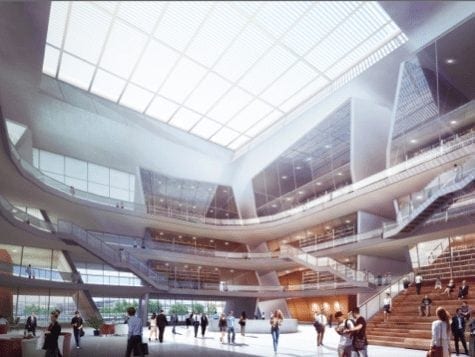

Chun Sen Bi An perspectives (above)

Chun Sen Bi An Housing Master Plan

COMPETITIONS: Once you have become established in China, it would seem that you almost can pick and choose between competitions and projects.

O’Connor: Right before the time of the Olympics, there were few foreign firms working there so we were interviewing clients as opposed to clients interviewing us. And every time we would go out, we would be involved with another project, or another competition. It all started in kind of a shaky way; but that’s kind of how it evolved.

Amber Bay Resort Development, Dalien, China (2005-)

COMPETITIONS: MRY is not a mega-firm like SOM or Perkins+Will. So competing on such an international scale as MRY does would almost seem to be an anomaly.

O’Connor: When I joined the firm, it was a medium-sized studio firm known for high-end design. Back then the big firms didn’t have so much focus on design, and the small firms didn’t have so much capacity or experience. That has changed now. We were very nimble—we only had the one office in Santa Monica, whereas we now have two offices, Santa Monica and Shanghai.

China has been a big piece of our experience. But earlier on we worked in Japan, in Sweden, the Philippines, and, at one point, sixty percent of our practice was actually in Germany. When the wall came down in Berlin, we undertook a huge amount of work in Germany.

COMPETITIONS: I’m familiar with your Tegel project in Berlin when Charles Moore was still leading the firm—a result of the Berliner Internationale Bauaustellung (International Building Exhibition). Was all this a result of Charles Moore’s doing, or how did that happen?

O’Connor: John Ruble was the lead partner on the Tegel housing project, and he worked closely with our founding partner Charles Moore, who contributed much of the design in the early stages. When the wall came down, there was a huge demand for housing, particularly in Germany. Tegel was already built, and the Germans obviously wanted something different. We brought something a little bit different from the German firms—that kind of California experience: the indoor, outdoor, the landscape. So we were included in shortlists for a lot of competitions. Things were going very fast. Social housing was a huge part of the need. That work was built on our reputation in Berlin. So people knew of us.

COMPETITIONS: So was Sweden the next stepping stone?

O’Connor: Yes. We didn’t do any marketing. Actually, we didn’t do any marketing for any of these. One day we got a phone call from the Planning Department in Malmö. They had seen one of our projects in Berlin, and asked, ‘would we come up to Malmö.’ We said we would, got off the phone and said: Where is Malmö? So just from that phone call we started a collaboration, working in Malmö and in Sweden.

Potatisakern Housing and Villas, Malmö, Sweden (1988-2002); Perspective and plan

Tango: Bo01 Housing Exhibition, Malmö (back to back in interior block parcel) with

bridge connecting Sweden and Denmark seen in right background

Work came from a number of people who had seen our work over the years. Clients in the Philippines, others in Japan had seen our social housing project in Berlin. They wanted to do high-end housing. I remember that the German architects weren’t too fond of Tegel, and I asked them once why they didn’t like it? And they said, ‘well, it’s not honest. It doesn’t look like social housing.’

COMPETITIONS: Shortly after that was built, one of my Berlin architect friends said it had a reputation of being ‘a good address.’

Going back to China, after your first competition in China—Century City— you started getting more work in Asia: in Hong Kong, the Philippines, Taiwan. But after that first project in China, what came next?

O’Connor: That was the first one in Beijing; but the one that really put us on the map was Chongqing. It was a competition for a very large housing project—and mixed-use. At that time, there was a huge demand for housing in that part of China. When the real estate end of it was launched, it became very well-known. They had sold more units in one day than anyone else—I believe it was over 300 units. That was out of 5,000 total! Apparently, you could even sell your place in line as a buyer.

China, although a big place, is also kind of a small place. So at the end of the Chongqing project, we got many offers to do projects. In those early days, before the Olympics, a lot of it was housing and mixed-use. After that, we wanted to bring some of our practice from Santa Monica to China—meaning we do a lot of higher education and masterplanning for university campuses. So now we’re doing more of that there. Shanghai Tech University Campus was a huge project for us. It was an international competition in which we were shortlisted and won. But instead of just winning the masterplan, we ended up designing about 85% of the buildings. The reason we didn’t do more was that we didn’t have the capacity to do any more. Originally it was just supposed to be the masterplan; but then the client decided they wanted us to do everything.

Every member of the Shanghai Tech Campus Masterplan design team, which included Buzz Yudell, John Ruble, Michael Martin, Anthony Wang, Chris Chen and Ann Shu, brought vitality and insightful thinking to the competition process. Buzz Yudell’s invaluable understanding of humanistic and cultural forces contributed greatly to our direction in the Campus planning. Michael Martin’s in-depth lab and research experience set the stage for a 21st century research campus

Following on our win, we opened the Shanghai office. Chris Chen and Ann Shu now lead the MRY Shanghai office.

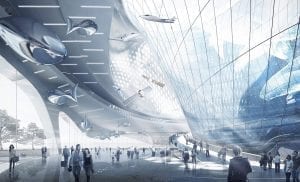

Shanghai Technical University: Plan, library exterior perspective, library interior view

COMPETITIONS: I recall that you once mentioned that what also helped in getting projects in China was lecturing at the Institutes.

O’Connor: That kind of happened by accident. In China you are always teaming up with an Institute (on projects) and, although they didn’t know of us at first, when we gave talks there, it was huge exposure. I also gave lectures at the Chinese architectural schools as a way of getting feedback; because it was very difficult to get feedback from the Chinese client—there was no dialogue in terms as to how it relates to Chinese culture, Chinese living. By giving talks at universities, students were very vocal, open, and questioning. So that was a way to relate to Chinese culture.

Beihang University Qingdao International Science and Education New Town, China

Town master plan (above)

Beihang University library (exterior, left; interior (right)

Beihang University Qingdao

International Science and Edu-

cation New Town competition

Team : MRY – ECADI with Arup

engineering and Lützow landscape design.

“Our concept for the project is to connect several separate sites to form a cohesive campus without barriers. We seek to offer learning spaces without physical boundaries.” – James Mary O’Connor, FAIA

COMPETITIONS: Do you think by virtue of so many Chinese students studying in the U.S. that they are getting better at planning. So I’ve asked, why aren’t the Chinese now capable of doing good planning? So many foreign firms are still involved in the planning process in China. The answer I still get is, ‘well, they aren’t very good at that.’

O’Connor: That’s still kind of true. It’s more because of Chinese emphasis on the building, the object. That’s probably true in other parts of the world as well. Urban planning takes a different kind of skill. Chinese architecture has all kinds of great firms doing all kinds of architecture; but I think that’s our way to continue there. There isn’t a huge amount of expertise in master planning: it tends to be quite mechanical and less about the experience of the place. I would say that is one of our fortes.

And there are different scales. The thing about Chinese masterplanning is that it’s colossal. We have a difference in scales of masterplanning from a district to a campus to a piece of a city, to regional planning. I think American training is very good for masterplanning. I would agree totally; I haven’t seen that. We’re no longer doing many housing projects at this juncture. We have segued into campus planning and education masterplanning.

COMPETITIONS: You have also done projects in Hong Kong. Hong Kong is part of China; but is it different working in Hong Kong?

O’Connor: It’s completely different from (mainland) China. When I went there, our local firm in Hong Kong was asking me ‘What’s it like to work in China?’ Some don’t do any work in mainland China. So it’s quite different. They have some aspects of China; but generally it has its own set of criteria.

Fire and Ambulance Services Academy, Hong Kong – Entrance (left), Aerial view (right)

It also has a speed of construction. We won an international competition there for a first Fire Training campus in Southeast Asia. We won that with a local Hong Kong firm, AKLF. Just about a month after the competition, I went down to see the site and couldn’t believe that they had already started construction. We hadn’t even gotten into schematic design; we had just won the project. They told me, ‘Well, the schedule is so short that we had to get a jumpstart on the construction.

COMPETITIONS: Were they doing that without construction documents?

O’Connor: They were building retaining walls, basing it on our competition. It’s funny, because when we win a large competition in Europe or in Ireland, that’s the beginning of the process. In a competition in Dublin for a new Grangegorman campus master plan, it took about two years with all the different teams, the client, and the community participation process. In Hong Kong for this project, they were saying: ‘Well, Mr. O’Connor, how much concrete do we need?’ The programming stage didn’t appear to exist.

COMPETITIONS: Have you also noticed a glut in the present housing market in China?

O’Connor: It has certainly declined these last couple of years. Especially on the east coast there was a lot of speculation, leading to a lot of empty buildings. That may be adjusting now.

Emphasis there has changed. Now it’s gone to educational buildings, campuses; and our work has changed with that. In the early days, everyone wanted to have that California building, with that lifestyle. The style was very important. But now we are doing a lot of research buildings, like with Shanghai Tech University. What they want now is the real thing. When I say ‘real thing,’ we have a lot of expertise in research and lab buildings. They want the core of that, the intelligence of highly efficient research buildings, not just the look of something to sell.

COMPETITIONS: One project mentioned was the EOFCO Eco-Valley projet.

O’Connor: That was another interesting competition—for about 3,000 acres. One of the largest agricultural companies in the world EOFCO wanted to build an experimental town, highly sustainable, about an hour off the seventh ring road outside of Beijing for research, but mainly agriculture. As a demonstration project, it could be built in a number of different places.

It was interesting how we won that, because we had never done an agricultural project before. Because of this, I thought we would really need some help; so we contacted the University of California Davis and asked them to be partners with us. So we worked with them, and when it came to the presentation, we asked to present first, so we could watch the presentations of the others who followed us. So when it came to the presentation, I said that this was so technically involved with agriculture that we had to include UC Davis’ Colin Carter, our Agricultural expert. As a result, we had them do the entire presentation.

At the conclusion of our presentation, I said that you couldn’t do a project like this unless you had agricultural expertise; thus we included UC Davis as the experts. It was interesting, because in every presentation after us, they were interrupted and asked, ‘Well, where’s your expert?’ And none of them had any experts or expertise in agriculture. So it turned out that this was the criterion that helped us win the project.

COMPETITIONS: MRY’s reputation for expertise and creativity in masterplanning competitions is well established. So having grown up in Dublin, you must have known the site of the Grangegorman campus there like the back of your hand. This must have given the MRY team a certain advantage in that competition, where the firm came out on top. To incorporate the scattered departments of a university into the site of an abandoned mental hospital is in itself a work of art.

O’Connor: The team, including John Ruble, Buzz Yudell and John Mitchell were vital to the insights and thinking that led to the proposed Masterplan. We each came to the process with experience and knowledge of other projects we’d undertaken worldwide. My own intimate knowledge of the specific locale made it easy to share with others the natural pathways and links to the city. John Ruble’s insights into the challenges faced by a twenty-first century campus were enormously important to our thinking and process.

Grangegorman campus Masterplanning Competition

Grangegorman masterplan team

MRY – DMOD architects

with Arup engineering, Healthcare – Bryan Lawson, Conservation Architects – Shaffrey and Lützow landscape design

Images from top: aerial view, model, view to green, interior pathway perspective

“The goal of the Masterplan design team at Grangegorman has been to create a place full of vitality and architectural value which will enrich the city fabric and serve the needs of not only the immediate users of the new urban quarter, but indeed the entire community of Dublin and Ireland in the twenty-first century and beyond.” -James Mary O’Connor FAIA

For a descriptive audio narrative about Grangegorman by James O’Connor:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F9YLrORepk4

Note: all images provided the courtesy of Moore Ruble Yudell.