Whereas international competitions for real projects have become a rarity lately, Korea is a welcome exception. Among the plethora of competition announcements we receive almost weekly, several have ended with foreign firms as winners. But the history of welcoming international participants does go back several years. One notable early example was the Incheon Airport competition, won by Fentress Bradburn Architects (1962-70).

Among the more recent successes of foreign firms was the Busan Opera House competition, won by Snøhetta (2013-) and the Sejong Museum Gardens competition, won by Office OU, Toronto (2016-2023).

Busan Opera image courtesy ©Snøhetta

Sejong Museum Gardens Image courtesy ©Office OU

Heatherwick Studio claimed first place in the Global Art Island invited competition (2024) where the international jurors included Tom Mayne (USA), Bjarke Ingels (Denmark), and Ben van Berkel (Netherlands).

Global Art Island Competition Images courtesy ©Heatherwick Studio

Herzog de Meuron was awarded first place in the Seoripul Open Storage Museum competition, which was covered by us in detail (see: https://competitions.org/2023/12/seoripul-open-storage-museum-in-seoul/). Of the five expert jurors in the latter competition, Grace La (Harvard GSD, Professor), Cambridge, and Fernando Menis (Menis Arquitectos, Architect), Spain were two foreign jurors included on the five person panel. The winning team of the important Banpo-Hangang River Connection Park and Cultural Facility competition in Seoul was led by LEEON Architects, a firm with strong history and connections to Paris. The two outside jurors in that competition were Michael Speaks, Dean of the Syracuse University School of Architecture, and Jung Hyun-tae of the New York University of Technology (more on that later).

We find that the inclusion of foreign jurors to be a significant sign that outside participating firms can rest assured that their entries receive serious consideration.

One website that lists numerous competitions, mainly located in Seoul, is Project Seoul (https://project.seoul.go.kr), where one can find any international competition also available in English.

The Changdong Station Transit Center Competition

Although not limited to local participation, foreign presence in the Changdong Station Transit Center competition was hardly of consequence based on the list of the five finalists—all South Korean (A requirement that international firms collaborate with a local Korean firm to participate was not unusual).

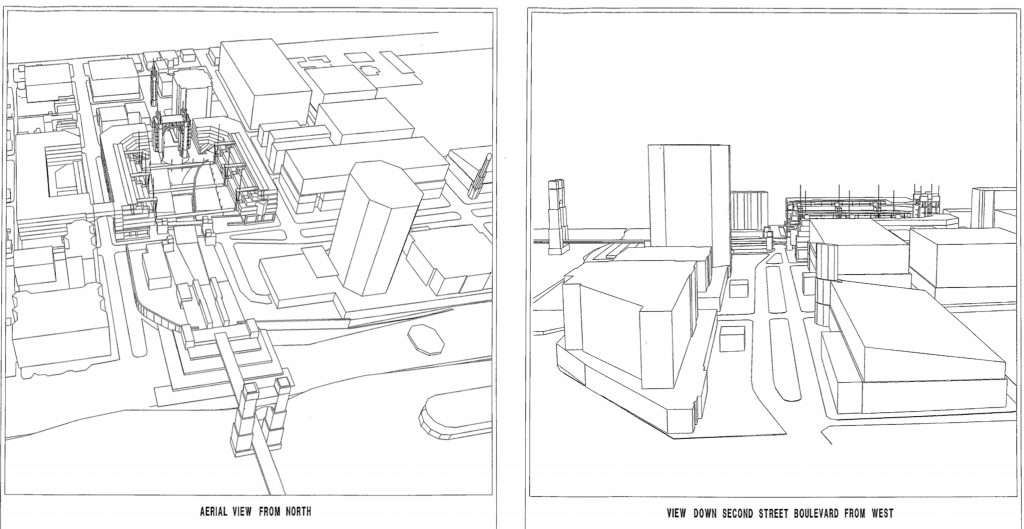

Aerial view of Changdong Station competition site

To any outside observer, mention in the competition brief that the names of jurors would not be released until the expiration of the registration period would certainly have given outsiders pause. Despite all this, the competition appeared to be well administered and the five finalists did reveal some solid, creative responses to the challenge, focusing on a mixed-use program in addition to its infrastructure requirements.

[eme_events order=DESC limit=100 scope=future showperiod=monthly category=1]

[eme_events showperiod=monthly category=2]

One thing about competitions, and having the fortunate experience I’ve

had, I’ve really learned that being ambitious for your client and society

is hugely important. – James Cheng

This is Thursday, April 11, 2024, and I am in the office of emersion DESIGN with architect James Cheng and J.T. Spence, the latter the former planner of the City of Covington, Kentucky, who was responsible for initiating the Covington Gateway Competition in 1993, won by James Cheng. -Ed

Architect James Cheng (left) Prof. John T. Spence (right)

COMPETITIONS: A question I almost always start off with: At what point in your early life did you decide to become an architect?

James Cheng: It really all started when I was in junior high and high school and really loved my art classes. So I told my dad, who was a chemical engineer, that I wanted to become an artist, and he said, there is no way I’m going to pay for you to become an artist. He had just come back from New Orleans where he saw all these starving artists painting and trying to sell their paintings. So he suggested that I try architecture. We did have a family friend who was an architect. So he had me talk to him, and my dad then found a program for rising high school seniors at Cornell—a little like a summer camp for architecture. This happened to be a wonderful fit for me; but I would not have known about it otherwise at the time. Having been involved in the Arts community, such as the Contemporary Art Center, I can see how difficult an artist’s life is. So I feel really fortunate that I ended up in the architecture profession.

COMPETITIONS: After Cornell, was the Covington competition the first one one you ever entered?

JC: No, I believe I entered a competition for Spectacle Island with some friends; and then there was a small house competition.

Model of Covington Gateway competition winner ©James Cheng

COMPETITIONS: As for the Covington competition, besides our announcement of it, it was pretty well publicized, even internationally. At that time the National Endowment for the Arts had begun to support competitions and may have provided some support for the Covington competition.

J.T. Spence: Jeffry Ollswang (competition adviser) may have somehow been involved with that; but the City of Covington was responsible for the entire support of the competition. It was well publicized: we did posters and mailings, and we received 110 entries globally, from Australia, Japan and seven countries.

JC: I often went to the DAAP library (University of Cincinnati) and may have seen it in COMPETITIONS magazine there.

COMPETITIONS: We never met when you won the competition in Covington. But I was quite familiar with it as we had published an announcement about the competition in our magazine and I was present when the entries were set up for judging. I wondered that the Mayor of Covington never showed up for the events I attended, and thus thought this might be an unfortunate omen for the further development of the project.

JTS: That’s not as impactful as you might think, because Covington has a weak mayoral form of government. Moreover, our mayor had just returned from spending two weeks at the Mayors’ Institute of Design (in Washington) with its founder, Charleston Mayor, Joseph Riley. So he was very supportive of the idea of a competition. It was the other four elected officials that had no outward appreciation for what it meant. So I think they were less motivated to have the Mayor get credit for something in the city and (give the appearance of) diminishing their leadership role in the city.

COMPETITIONS: I was very aware of the mission of the Mayors’ Institute of Design. We were in continuous contact with the people who were running it at the time.

JTS: They gave us a very different vocabulary about what we were trying to get across to the elected officials, which was a vision of Covington’s future.