333 Wacker Drive – view with Chicago River in foreground (photo: ©Barbara Karant)

COMPETITIONS: When you are called on to design a ‘foreground’ building for a corporate client—although it’s usually an office building, it could be any number of building types—how do you balance the private and public interest beyond the usual zoning regulations?

left and below

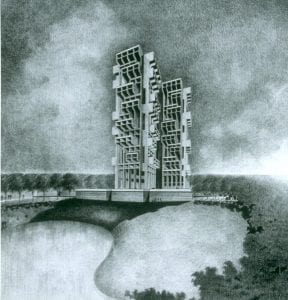

Gargoyle Club Prize

Best Architectural Thesis, University of Minnesota School of Architecture (1961)

Theme: Hospital Project

Images: courtesy William Pedersen

Pedersen: The interest of the client as it relates to the quantity of the construction they wish to place on a site is perhaps the most difficult issue, particularly during the 80s, when a tremendous amount of construction was taking place in the United States, and one more office building was not hailed by anybody as a contribution to society. The situation has changed rather dramatically in the 90s, when almost none of them are being built; so the issue is not as pressing. But there always is the question, ‘Is a building, given the bulk proposed, appropriate for its specific condition?’ One’s ability to deal with that issue is somewhat limited because zoning establishes what is of right, and not of right. Therefore, the battle has largely been fought prior to our entrance on the scene.

Past that point, the relationship of our buildings to a specific context has been a fundamental issue of our architecture. This is particularly how we take tall buildings, which are in themselves somewhat insular, autonomous and discrete, and bring them into a more social state of existence. That’s been the subject of our study for the last twenty years. We’ve developed strategies for doing that, of which I’ve spoken at length. The preoccupation of making the tall buildings—part of a more continuous, overriding fabric—that’s been central to our architecture.

COMPETITIONS: The most obvious argument against contextualism—as many people understand it—would be the Pompidou Centre in Paris, which has turned out to be the most visitied and popular building in that city. Wouldn’t that seem to give architects a good argument for doing something different? Was that even a lesson?

WP: Juxtaposition is a fundamental contextual strategy; but it has to be used sparingly and has to be introduced at exactly the right moment for it to have a powerful effect. For example, the Seagrams Building on Park Avenue—before any of the other buildings followed suit—was exceedingly powerful and very successful as a result of the juxtaposition at that particular place. I would argue that our building in Chicago (333 Wacker Drive) is an equally successful contextual building. It’s on the only triangular site of the Chicago grid at a bend in the Chicago River, and it sits within a context of totally masonry buildings, largely of the classical derivation. Somehow the relationship between those very distinct parts works. We were asked to build a building right next to 333 Wacker Drive, which did not occupy a unique geometric piece of property, but in fact became more of a continuation of the street wall leading up to 333 Wacker. We elected there to utilize a more Classical language in total juxtaposition to our own 333 Wacker in an effort to try to achieve the continuity of the wall that we thought was necessary, but also to maintain that poignancy of a juxtaposition to 333 Wacker Drive to the rest of the context. It would weaken it tremendously if it had been reproduced next door.

The same is true of the Pompidou Centre. If one were to tear down that section of Paris around it and build a number of Pompidou Centers there, it would lose its impact, because ifs impact is an object set within a very careful framing in that traditional neighborhood. Without the dialogue between the two, the game is over.

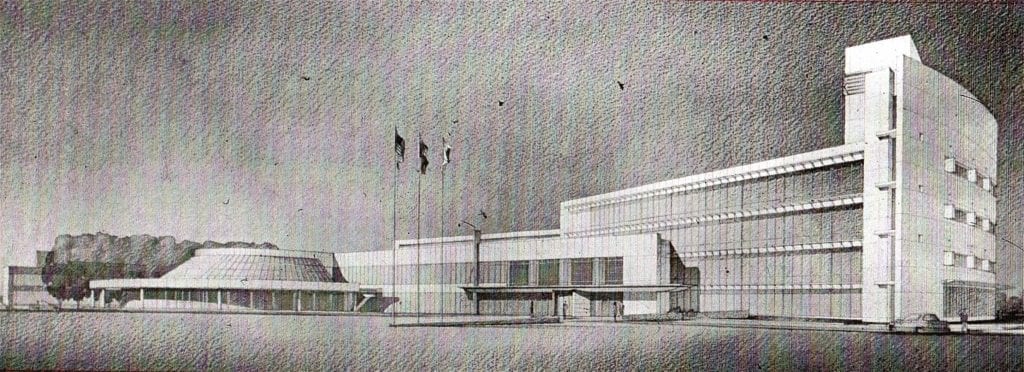

AAL Hqs. building addition (1971), Appleton, Wisconsin

AAL Hqs. original building (above images courtesy William Pedersen)

COMPETITIONS: Most people seem to believe that 333 Wacker is the best building you have done. Maybe it was the time and unique site. It was one of those projects where one announces, ‘Well, here I am.’ Sometimes it’s difficult to top a wonderful building like that, though you may believe your next building is the one you like best.

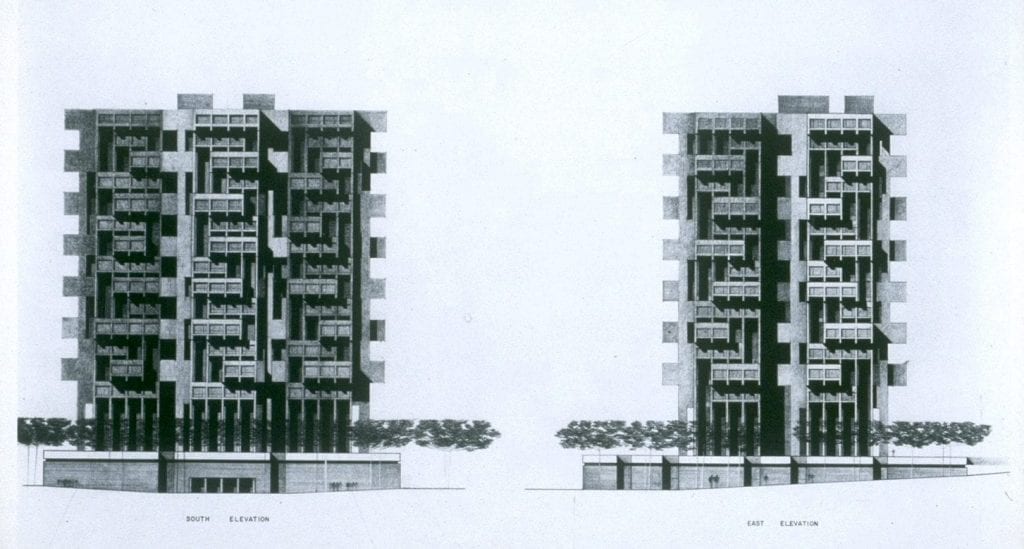

WP: I think that 333 was a product of my sensibility at that point in time. It was a building that tended tobe an intuitive response to the site. In terms of it language, it came out of a couple of other buildings I had done immediately prior to that—one being the Aid Association for Lutherans in Appleton, Wisconsin, the other being the Brooklyn Criminal Courts Building, which had very similar geometric ideas in terms of its relationship to context. The very conscious attitude of trying to make the tall building part of a larger urban contet preoccupied us for the next five years. As a result, we used a more classical language to try to develop connecting strategies, because a Classical language is largely built on ideas of connection of pieces and parts, one to another…buildings connect well because they have parts that are combined and are part of a central language.

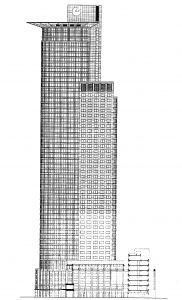

However, that was not a productive period for my/our work, and about 1986 we were asked (to take part) in Germany for the DG Bank building in Frankfurt. I ahd been teaching at Yale a semester previous to that competition and had been thinking about some new strategies—of ways to fuse the more Classical language with the Modern through the penetration of volumes. So the combination of a language, which tended to be more dynamic on one hand and less formal on the other was, I think, realized in our Frankfurt project. While people may like the 333 building the most, I think that of all of the work that I have done, the DG Bank building is the most provocative. Contrary to 333 Wacker, it develops a series of parts, each of which has a very specific urbanistic role. I call it a building of three parts. It is the reconciliation of a bifurcated context—the other to the residential. The tower tries to reconcile those two conditions, the two parts of which are pulled together by a third part, which is a vertical skewer representing the core of the building.

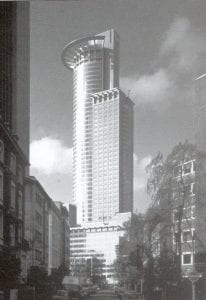

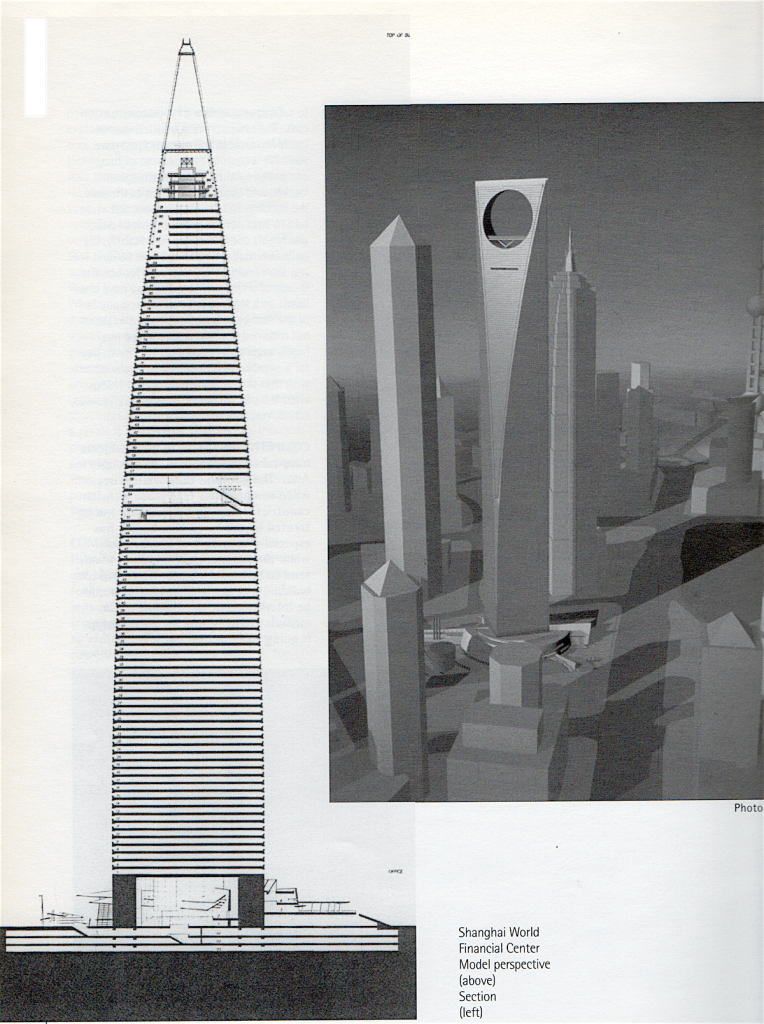

My work more recently has perhaps come closer to 333 Wacker Drive—the Shanghai project, or the competition which we just won in Pusan, Korea, the DaeWoo project. Thse two are monolithic buildings, buildings of a single part. By virtue of their incredible size, their ability to fit into a context is limited; therefore I try to dal with them on a more abstract sense.

DaeWoo Tower project, Pusan, Korea (1996) Image photo: ©Edge Media

COMPETITIONS: In the case of the DGBank building, it is easy to recognize the two main parts; but is this a simple matter of adding and subtracting? When do you know when to quit adding or subtracting from those two design elements. This is often a common problem in architecture. Here it would seem to be even more obvious.

DG Bank Building rendering (1986-93), Frankfurt, Germany Image courtesy KPF; photo: ©D.Gilbert

WP: Up until the time this building was introduced, the city of Frankfurt had a 150 meter height limitation on high-rise construction. The building at its base matches the other buildings on the street, which are all 22 meters in height, a height which is pulled over into the building itself, then steps up to 27-28 meters. Directly across the street (Mainzerlandstrasse) is a building of 46 meters, which is essentially the height of that lower bar.. The 150 height is marked by the back of the residential piece on the tower. So it is not an arbitrary height; it’s a height that tries to historically record that datum. The remainder of the building rises to 206 meters.

COMPETITIONS: Does it face out to the river?

WP: The crown faces to the old city, to the airport and towards the river. So every piece of the building has it urban strategy. I isn’t arbitrary.

COMPETITIONS: Gong back to your AAL building in Appleton, Wisconsin—your first big project. You worked out three different schemes to present to the client. Do you still try to come up with several ideas for each project? Is three somehow a magic number?

WP: We do work in a comparative process. We feel that a comparative method allows for the client to participate with us in the design process: it’s easier to explain why certain ideas were rejected through a comparative process than it is through simple explanation of a single scheme. To illustrate this, we were doing the Procter & Gamble Headquarters seeral years ago and presented four massing studies to (CEO) John Smale. He looked at them and side,, ‘For the first time, I understand what I am trying to accomplish here with this building. I want to be able to draw the old building (built in the 60s) and the new building together in such a way that together they represent a single World Headquarters for Procter & Gamble. Why you have shown me is interesting; but it doesn’t really connect to the old building visually in a way that symbolizes a single place.’ So we went back and developed the scheme which was actually built, which brought the old building and a new building into a single L-shaped figure. Both of those structures framed a large internal garden. As a result, it is our sense that Smale’s thought process triggered a response on our part. In a sense, we were co-authors of that design. Thus, we like to draw our clients into a comparative process plus it forces us to look at the project from all perspectives.

COMPETITIONS: The distinction between art and architecture sometimes get blurred. Thus, a lot of architects feel compelled to explain their buildings. But if a building is primarily sculptural, such as Frank Gehry’s, it’s so abstract that a client might feel reluctant—or even foolish—to ask for an explanation.

WP: It depends on one’s sensibility. For myself, I like to build a very clear rationale. As a result, the verbal explanation and the design itself tend to have a strong correlation, one with another. I do not believe, however, that architecture should rely on verbal explanation.

COMPETITIONS: The World Bank building, which was a competition in Washington, D.C., presented special problems, partly because building in the capital brings with it specific limitations, in this case it was the creation of a ‘block’ building. How did you approach this?

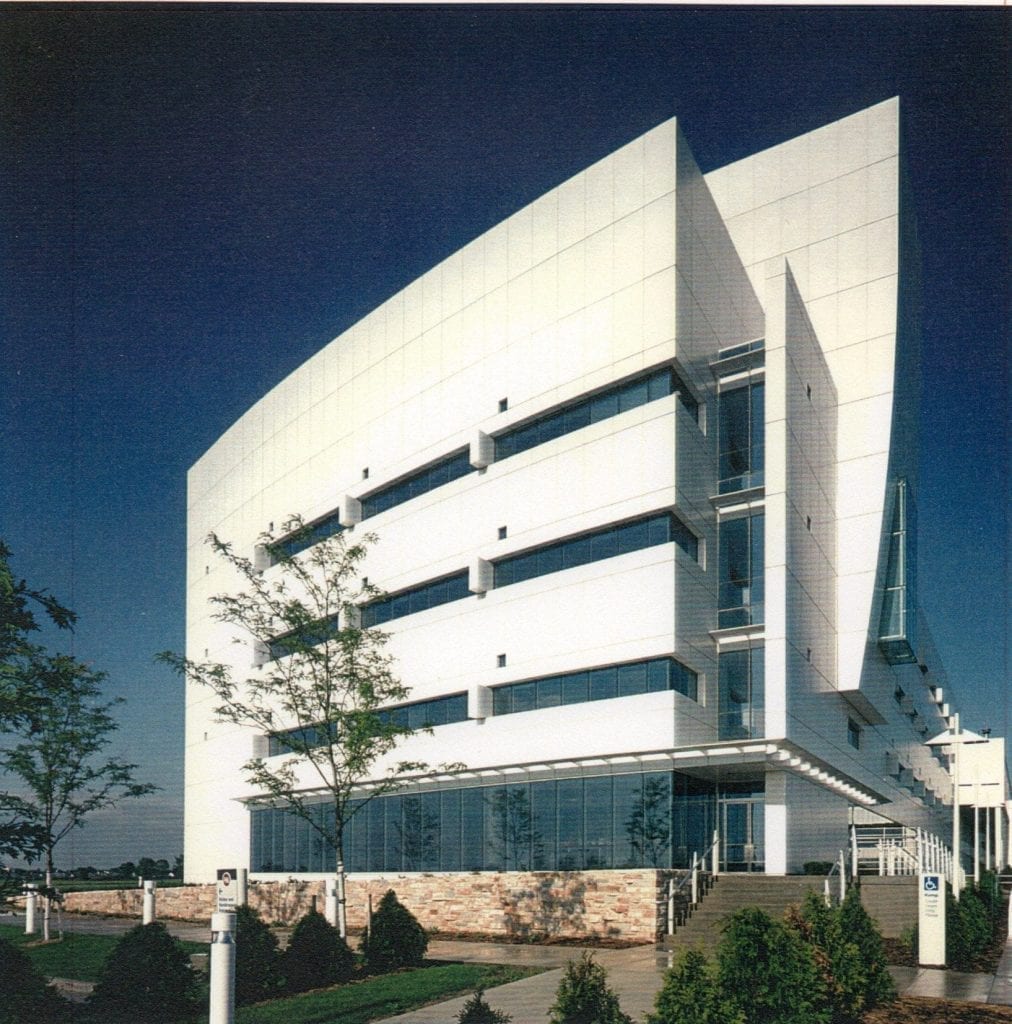

World Bank Headquarters – Competition (1990); Completion (1996) Photo: Pottie

WP: Our approach to the problem was key to our winning the competition. There are two existing buildings on the site that they wished to retain for a few years, but then ultimately to demolish in phases. These buildings are called the D and E buildings—built in the 60s, one by Gordon Bunshaft, and the other by Vincent Kling. We looked at those buildings and thought they were still serviceable. The Bank was in an overall more advantageous position if they could achieve their block masterplan earlier, rather than later. So we developed our scheme in a way that those two buildings were part of the overall master plan. The other point was that they wanted to build about 2 million SF on that site, and, as you know, Washington has a 130-foot height limitation. Twelve floors is about the maximum which will fit within that limit. So we challenged that and were ultimately able to get thirteen floors, which helped dramatically.

The biggest problem for the Bank was to be able to introduce enough natural light internally, such that they could allow the interior of those spaces to be fully illuminated by natural light. Given the density of the site, this was an immense problem. We decided to develop an internal space, having a sufficient dimension so that this could actually happen. Keying off the two existing buildings, we then took two other blocks and composed a pinwheel to frame a square, internal court. The court was essentially a cube in volume—150’ x 150’ x150’. When one goes into this space (the building is now finished), one is struck by the immensity of the space and the effect that natural light as internally within it. The offices facing into the courtyard are legitimately better than the offices facing out to the street. That really was the heart of our solution.

Ours was the only scheme to get internal light into the offices and down into the lower floors below grade. The manner in which we developed the pinwheel scheme allowed us to introduce two phases of construction. Also, that room is to reflect a sense of ommunity on the part of all the nations that are represented—surrounding that courtyard. The introduction of the architectural elements within that space was devoted to symbolizing the various cultures.

COMPETITIONS: There are a number of reports that the World Bank as a client initially overreached their budget substantially. How did that effect the design process?

WP: The building was built for about $125 SF. When you consider what is in that building—all the special functions etc.—everyone agrees that is a good number. What I think happened after the competition was that each of the competitors was asked to submit an estimate of their construction cost. The estimate we submitted was virtually identical to the number I just gave you. We were told that because of the competitive natures of the Washington market, and conditions present at the time, the building would cost a lot less. We were told to base our fee on that as well—which was highly contentious for us.

Frankly, that optimism that the building could be built for less than it ultimately was built for was the source of all the difficulty. It may have been based on a legitimate belief in the optimism of the market at a particular point in time; but it turned out that our estimate was highly accurate. It was a great price to pay for a number of people who were associated with that phase of the project; but we survived the process, and the Second Phase was, I think, run very well.

COMPETITIONS: Many of your projects have taken place abroad particularly in Asia. The question that often arises when competitions take place in Asian countries is: how will an outside firm will be treated by the home client? This has especially been true of China lately, while the Japanese, on the other hand, tend to be model clients. Since you are building a tower in Shanghai, it would be interesting to know who your immediate client is and how the relationship is going to this point in time.

Shanghai World Finance Center (1996-2008) Rendering courtesy KPF; Photo: Edge Media

WP: The client is a Tokyo-based, Japanese construction company. One has to select the client very carefully. To now, we’ve been lucky. We have had excellent clients, working from Jakarta, to the Phllippines, to Tokyo and most recently a tremendous amount of work in Korea. In every case, we have been fairly treated, and a large percentage of these buildings are some of our best work. It’s worth the pain of a long plane trip.

COMPETITIONS: Based on some of the projects, which have been built in the Far East recently, like the Tokyo Forum and some of your recent projects, one might assume that there is more freedom to design more boldly abroad than is presently the case in this country.

WP: One can counter that (argument) with specific examples; however, it is generally true. In the case of Viñoly’s Tokyo Forum, that was an international competition, a highly specialized project, and the reputation of the Tokyo government was at stake. It was also built and funded during the heyday of the economy. It was a remarkable achievement.

We have been able to build buildings (abroad) that are as interesting architecturally, mainly because they are looking in those countries for something special. In the case of Korea, the economy is very strong, their physical environment needs to be totally resuscitated, and they see this as an opportunity to present themselves to the world market in a positive way. So they want the architecture to speak for that.

COMPETITIONS: When you were deciding to become an architect, was it something that happened on the spur of the moment?

WP: Although my grandfather was an architect, and my father was involved in architectural pursuits, when I went to the university of Minnesota, I went not only to study architecture, but also to play hockey. I must confess that in the early years, my focus on hockey was a little stronger than it was on architecture. But it meant that I had to make a choice, and when I had made that choice, early on, it gathered momentum.

COMPETITIONS: You seemed to be able to make all the right moves at the right times. Do you think there is some way for the associations, i.e., AIA, to promote some system whereby young talent will get more exposure?

WP: I remember thinking as a young man about my future prospects as a professional—being tremendously dismayed about the possibility of finding a client and doing a building, because it all seemed so remote. There were certainly no clear-cut steps one could take to allow one’s talent to emerge. One had to make associations that would lead to a potential building; but all those steps were very unclear. Certainly the examples that we have in Europe, particularly in France, where a competitive system is established that allows young architects to enter and, in fact, to (enhance) their position at an earlier age. Also, it is enormously good for the vitality of the profession. Competition, in an abstract way, is the essence of life. You think of the good architects that have achieved their status as a result of the competitive system and wonder what would have happened had they not (had that opportunity).