with Stanley Collyer

Bundeskanzleramt Berlin Competition (1996); Completion (2000) Photo: courtesy Schultes Frank Architekten

COMPETITIONS: In our last conversation, we talked about the whole issue of Berlin’s identity and what approach one should use in reconstructing the urban fabric between East and West—where the wall used to be.

Axel Schultes: Maybe I learned something during a recent lecture I gave in Palermo (Italy). Afterwards, some German specialists in philosophy and German thinking—brilliant people, I must say—came up to me and said, ‘What you said about Berlin and what you are doing there with the Federal Chancellery (Bundeskanzleiamt), for us is what Ernst Bloch and Walter Benjamin talked about, especially when they looked at Italy and the cities in Italy. We noticed immediately in your work that (same) issue of porosity.’ Both used this term: Benjamin wrote a small article on Naples, and Bloch wrote about Italy as a whole.

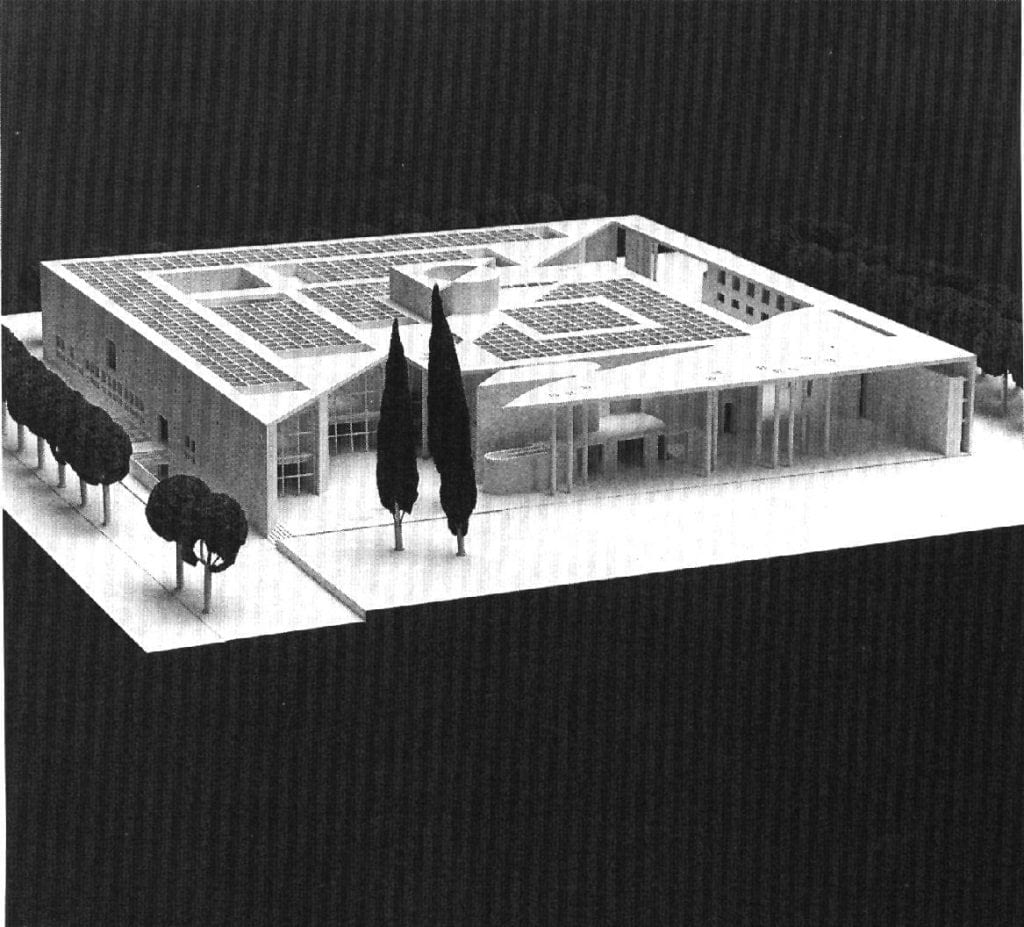

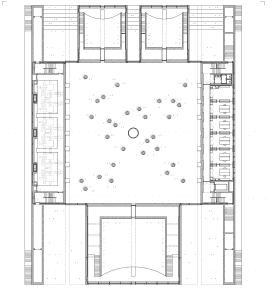

We always had a tendency to avoid the term, ‘transparency.’ Transparency is usually the use of glass to make buildings less alienating to someone outside. But for us, glass is no material to create spaces; so transparency as we see it is depths of spaces or layering. Porosity is something much more precise—what we strive for. We wanted the same effect in Friedrichstrasse (Interior Mall): it should not be this close-up thing of the Galeries Lafayette (Jean Nouvel) or Ungers, where you only have some holes in it. Porosity for us is like a sponge—to enable a building to fill up with life, to turn a private space into a public one by penetrating it with a public space. The old buildings in Berlin are examples of this, with two, three, sometimes even four interior public spaces.

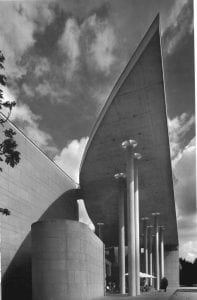

Berlin Baumschulenweg Crematory (1993)

COMPETITIONS: You are referring to the interior courtyards (Hinterhöfe)?

AS: Yes. Nothing of this sort exists anymore in Berlin. Most buildings (at the street) are flat, sometimes elegant, sometime ugly. The Galeries Lafayette, with all its glass, is as closed (to the outside) as one of Unger’s sandstone buildings. It’s the same issue in the construction of every building. Take, for instance, the Berlin Schloss (the palace in the center of Berlin), which was completely demolished after WWII, and which some people think should be resurrected. This has been on our mind constantly.*

It would be such a contrast to urbanism—needing to punch holes in it to get inside—open to all the people and all walks of life. I can give many examples of this, for me very northern, very restrained, very alien to everything which infuses a culture with life. All the people here like Kohlhof, Ungers, Kleihues, etc.; all have that tendency of closing. Even Libeskind—and maybe he doesn’t think about it or want to have it appear in such a manner—does it with the Jewish Museum where there is no penetration. There is always this hiding, this animosity to the urban fabric. They are not interested in breaking it up.

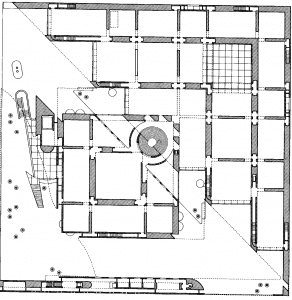

Bonn Art Museum Above photos: ©Stanley Collyer

Bonn Art Museum – Competition (1985) Completion (1992) Images: courtesy Schultes Frank Architekten

This is what I admire in the ‘southern’ cities like Cairo. Even in the case of the cemeteries, these architects have been aware of these porosities of stone, even if it is very thick and massive. There are always some enclosures connected by penetrating throughways: double and third wall with staircases, looking in the big rooms, hiding in the smaller ones. But they are all connected, never separated. You are reminded of the whole, even if you are in the tiniest little space. For me, this is one of the most important qualities. All the houses, from Madrid to Iran, are looking into the center. The always have an awareness of what is going on.

COMPETITIONS: Aside form the Chancellery, what new project are you working on?

AS: Here is a project south of the Spreeinsel (Spree Island) not far from the center. To arrive at the design, we looked to find something (which we can use) and here it is (showing an interesting wood formation). The client is very happy with this: of course it is large, but not by Manhattan standards. It is a building for small offices, not a building with any particular style. But I am not interested in style anymore.

COMPETITIONS: What about the style of the Chancellery?

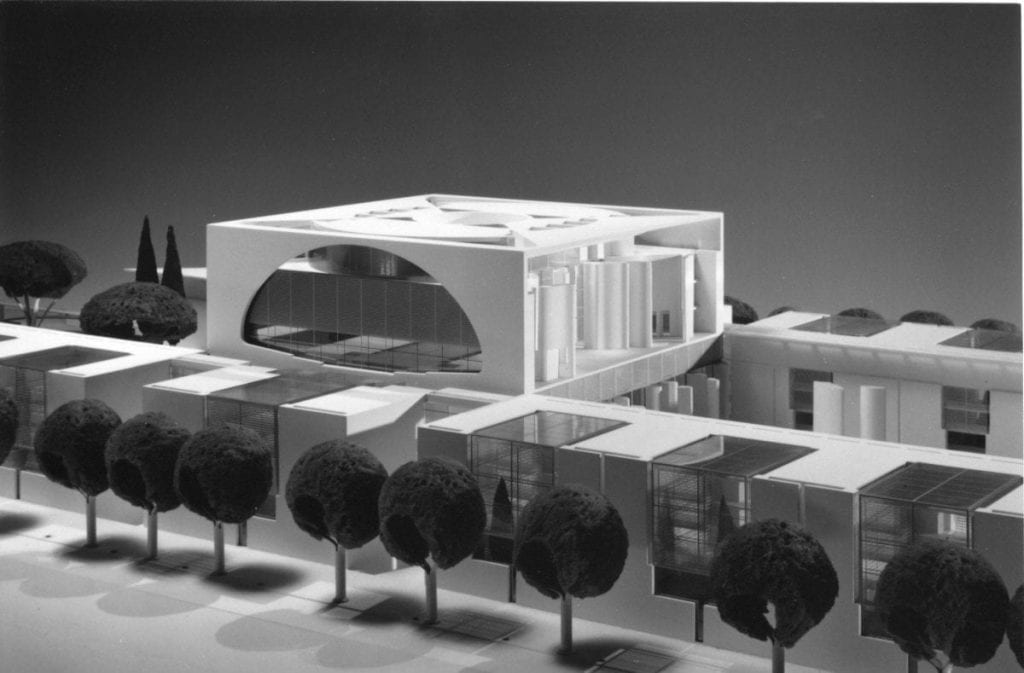

Bundeskanzleramt Berlin – Competition (1996), Completion (2000); Photos courtesy Schultes Frank Architekten

View to rear of Chancellery – Photo ©Stanley Collyer

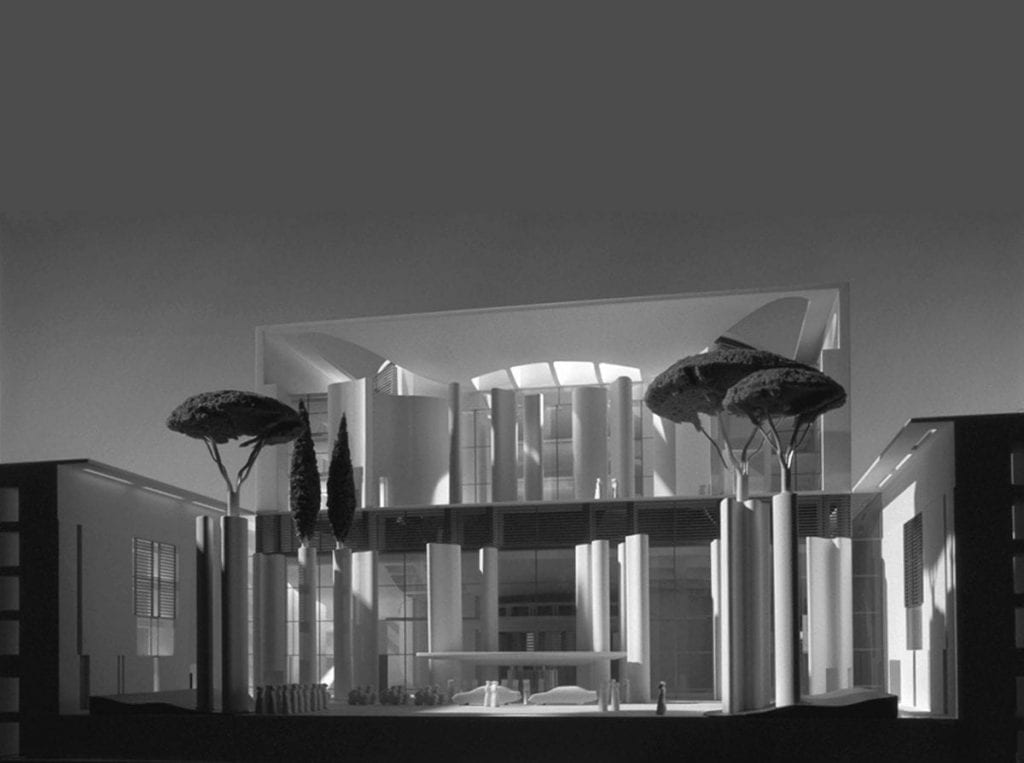

AS: The design is supposed to say something about the idea of reconciliation (Versöhnung). Someone wrote about the Chancellery that it is much more like a villa, more human. This is in contrast to the normal image of German state institutions. In this case, we tried to project the idea of (voluntary) reconciliation of the populace with the institution of the state. The trees in front can facilitate the softening of the building. It is our hope to create a public place by using a language which is not official. The Chancellor was quite sympathetic with this idea, so we try to go further.

COMPETITIONS: So this is to be the new German White House? The one in Washington doesn’t look authoritarian either.

Bundeskanzleramt competition proposal images Courtesy Schultes Frank Architekten

AS: It is so easy to lose the seriosity of serenity of classical architecture. To do it a modern way, and especially to achieve the seriosity we were talking about, our difficulty in handling this design was that these spaces—and here we are interested in architecture mostly in spatial terms—are not official; they are intimate. So our task was to create space by means of mass. We hate to use these glass walls and thus cheat people, and we are cheating them anyway to an extent. We see these walls as being in a process of opening and closing, but not being doors in the real sense. The columns are intended to be like islands, or pillars, in a stream. They are almost like invaders, or deputies, for the common people who can’t get inside. They are invading these hidden spaces, and they even climb the big stairs inside, get into the garden. The idea is to make the glass disappear by means of mass and shadow.

COMPETITIONS: Did the wrapping of the Reichstag have any positive effect?

AS: I wasn’t against the wrapping, but I thought it was a very old idea. Everyone I spoke to about it was very positive. Bismarck once said that the German spirit is so heavy that they need to have halfa bottle of champagne at breakfast for anything of value to occur. So wrapping the Reichstag was a little like a half bottle of champagne for the Germans.

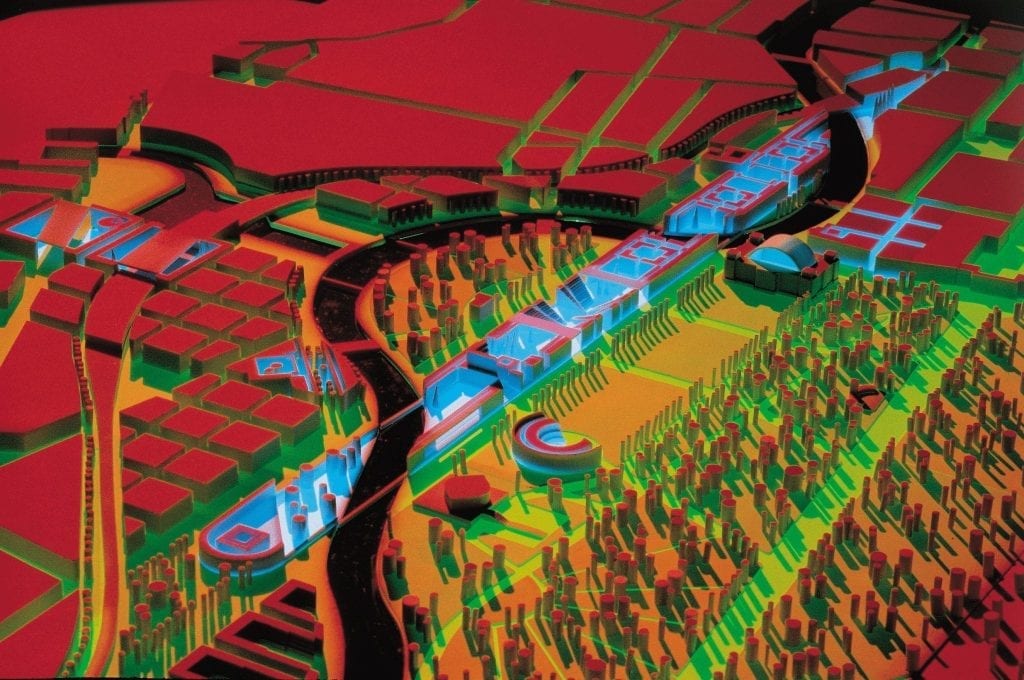

COMPETITIONS: Now you have competitions where the design of the building is only part of the challenge. A larger area is often included. Some architects complain about this. Thare are only interested in designing the building. In the case of the Chancellery building, you had already won the competition for the greater plan of the area (Spreebogen Competition). This must have made it easier to design the Building.

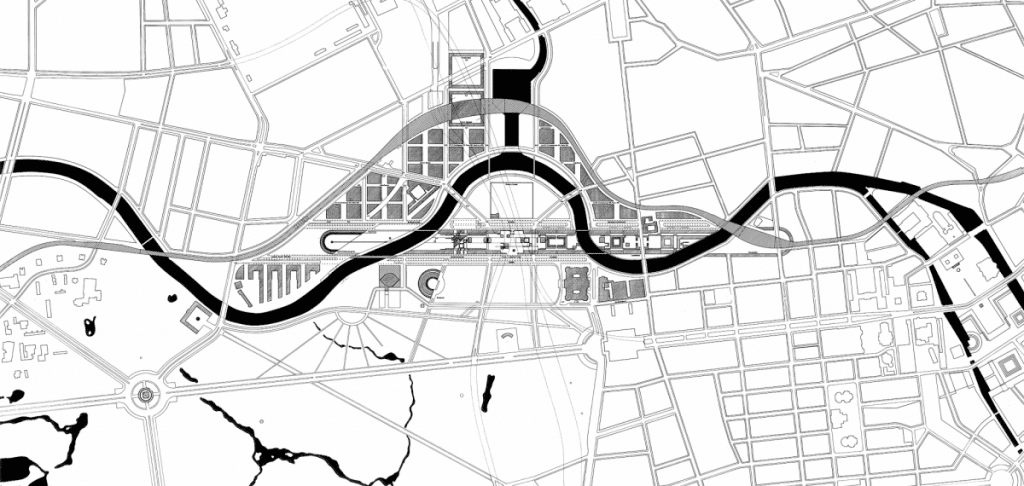

Berlin Spreebogen Competition 1993 (Winner)

AS: No, it didn’t. It was our last chance to do something in our own urban scheme. Of course we knew the client from the discussions about the urban plan. And the Chancellor first rejected the urban plan, for he thought it should reflect many of the things from the surroundings which weren’t all that important. Only part of the urban plan will survive—much of what was intended to extend into the East will not.

We had to project a strong image at a second urban level and, by making the building that important hindered us from doing our job as we would have done it as an architect. So we are a little schizophrenic about holding on to our own ideas, at the same time developing an architecture of energy. We look to make intimate interior spaces—out into the garden. To go up in height means to employ plastic means of architecture. This was quite an alien job for us, as if other architects should handle that sort of thing.

On the other hand, I remember, for instance, Exeter Library, where Kahn was creating space to the outside by means of cutting the edges and space on the inside by means of mass. He had these non-carrying walls with these big holes. For me, it was showing space by means of mass and mass by means of space. This led us to making a facade without a facade (for the Chancellery).

Galileo Control Center Weßling Oberpfaffenhofen, Germany (2008) Photos: ©Henning Koepke Fotographie

COMPETITIONS: What is the state of competitions in the EU (European Union)?

AS: The Germans, as usual, are much too obedient to the rules of the EC, and no other nation has followed this to the letter like we have. The French, English and italians publish these things in some obscure bureaucratic publication, and nobody knows about them. The Germans are so eager to show their allegiance to the EC rules that news of our competitions is broadcast so that all Europe knows about them.

I don’t think that the market is an architects’ market anymore. There will be a decline of ‘handicraft’ architecture. The big firms in the mainstream will rule the markets. There will be less and less opportunities for ’boutique’ firms. So I’m very pessimistic about architecture as a whole.

There are, of course, still some open competitions. There is one in Leipzig where I am one of the jurors for a museum, and we have 1.200 registrations. Assuming that there are 700 entries, it will be easy to overlook some good ideas. This is a crisis, especially for the young architects. In Germany, there are less and less open competitions, and this is not good for younger architects, who will find it more difficult to get out on their own.