by Dan Madryga

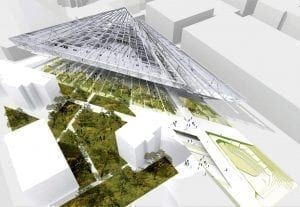

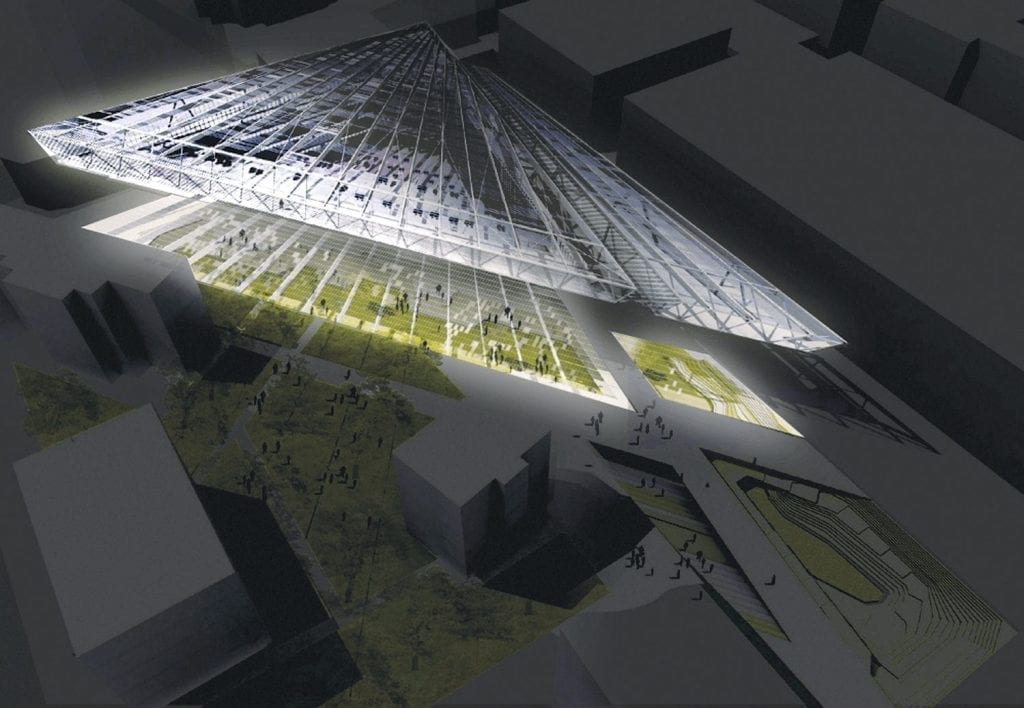

Winning entry by Bjarke Ingels Group ©BIG

Tirana, Albania might be the last place that many would associate with cutting edge architecture. The capital of a poor country still struggling to sweep away the lingering vestiges of the communist era, it is understandable that architecture and design have not always been a top priority. Yet in the face of the city’s struggles, Tirana is striving to reclaim and reshape its image and identity, and international design competitions are playing no small role in this movement. And while Tirana has yet to be associated with contemporary architecture, the implementation of these design competitions has introduced a handful of renowned architecture firms to the city with high hopes of bolstering the international image of Albania. In 2008, MVRDV won commission for a community master plan on Tirana Lake that will herald forward thinking, ecologically minded urban development. Earlier this year, Coop Himmelb(l)au won a competition for the new Albanian Parliament Building with a design intended to symbolize the transparency and openness of democracy. Most recently, Tirana can now add BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group) of Denmark to these ranks as the winner of the New Mosque and Museum of Tirana & Religious Harmony Competition, an ambitious project aimed to further rekindle a tattered Albanian cultural identity.

The recent efforts to renew and improve the physical image of Tirana can be attributed in large part to the city’s three-term mayor, Edi Rama. With his background as an artist, Rama has launched a number of initiatives over his decade in office, intent on improving the aesthetic image of Tirana. The design competition for the mosque and cultural complex can be viewed as the latest component of his “Return to Identity” project, which has gone to great lengths to remove the many unsightly and illegally constructed buildings that plague the city and help provide a clean slate for more progressive architecture and urban design.

The Mosque and Museum competition focuses on reclaiming a key religious and cultural identity that was long suppressed by communism. While Albania claims three chief religions—a Muslim majority alongside significant Orthodox Christian and Catholic communities—a strict communist regime ruthlessly banned religion. For over four decades, Albanians were under the thumb of an atheist regime where religious practitioners could face humiliation, imprisonment, and even torture and execution. The anti-religious campaign reached its zenith in the 1960s, when most Mosques and churches were demolished, and a select few with architectural significance were converted into warehouses, gymnasiums, and youth centers.

The revival of religious institutions began with the 1990 collapse of the communist regime. Yet decades of suppression took their toll, with the vestiges of Albania’s religious heritage essentially reduced to rubble. While the two Christian religions have since regained centers of worship, after twenty-one years of restored religious freedom, Tirana still lacks a mosque suitable for serving the sizable Muslim population. Only one mosque still stands in the central city—the historic Et’hem Bey Mosque—certainly a potent symbol of Tirana’s Islamic heritage, but particularly inadequate in size to accommodate the large numbers who would want to worship there on special occasions.

Hence emphasis in the brief concerning the size of the building: a grand mosque that can adequately serve 1000 prayers on normal days, 5000 on Fridays, and up to 10,000 during holy feasts. Supporting this mosque, the program also specifies the design of a Center of Islamic Culture that will house teaching, learning, and research facilities including a library, multipurpose hall, and seminar classrooms.

Another component of the competition program, the Museum of Tirana and Religious Harmony, moves beyond the realm of the Muslim community in an explicit gesture to bring together citizens from all faiths and backgrounds. Aside from presenting the general history of Tirana, the museum will focus on the city’s religious heritage, highlighting both the turbulent moment of suppression under communism as well as the religious harmony that has since been reinstated. Educating the public about Islamic culture and promoting religious tolerance at a time when relations between religious communities are strained throughout the world is certainly a noble objective.

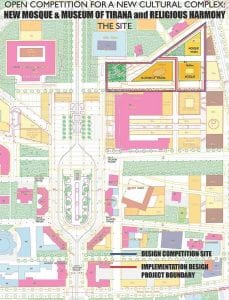

Underlining the importance of this project is its prominent site on Scanderbeg Square, the administrative and cultural center of Tirana where major government buildings share an expansive public space with museums and theaters. The square itself was the subject of a 2003 design competition that will eventually reclaim the urban center—at present a rather chaotic vehicular hub—as a pedestrian zone with a more human scale. Situated on triangular site adjacent to the Opera and Hotel Tirana, the Mosque and Cultural Center will be a highly visible component of Tirana’s urban landscape.

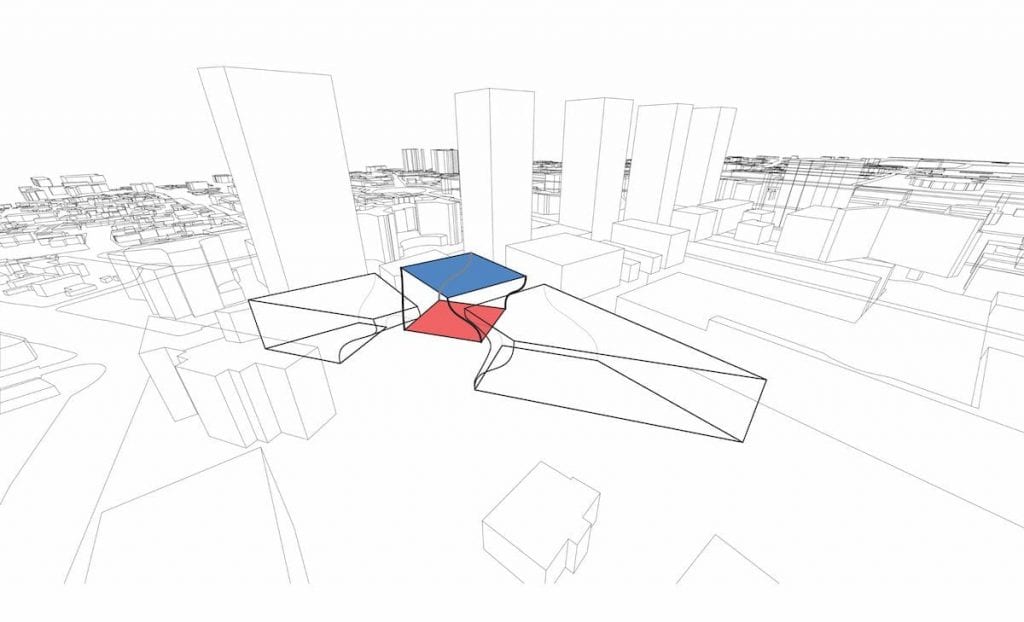

left: BIG site plan; right: rendering of Scanderbeg Square to appear after redesign (image by seARCH Architects)

The two-stage, international competition was organized by the City of Tirana and the Albanian Muslim community and advised by Nevat Sayin and Artan Hysa.

Over one hundred teams—the vast majority European—submitted qualifications for the first stage. In early March, the short-listing committee selected five teams to receive an honorarium of 45,000 Euros each to develop designs:

• Bjarke Ingels Group – Copenhagen, Denmark

• seARCH – Amsterdam, Holland

• Zaha Hadid Architects – London, UK

• Andreas Perea Ortega with NEXO – Madrid, Spain

• Architecture Studio – Paris, France

The designs were judged by a diverse European panel:

• Edi Rama – Mayor of Tirana, Albania

• Paul Boehm – architect, Cologne, Germany

• Vedran Mimica – Croatian architect; current director of the Berlage Institute

• Peter Swinnen – Partner and architect at 51N4E, Brussels

• Prof. Enzo Siviero – engineer; Professor at University IUAV, Venice

• Artan Shkreli – architect, Tirana, Albania

• Shyqyri Rreli – Muslim community representative

On 1 May 2011, the panel announced Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) as the winner.

The Winning Design: BIG, Copenhagen, Denmark

Partners-in-Charge: Bjarke Ingels, Thomas Christoffersen

Project Leader: Leon Rost

Project Team: Marcella Martinez, Se Yoon Park, Alessandro Ronfini, Daniel Kidd, Julian Nin Liang, Erick Kristanto, Ho Kyung Lee

Collaborators: Martha Schwartz Landscape, Buro Happold, Speirs & Major, Lutzenberger & Lutzenberger, Global Cultural Asset Management, Glessner Group

The singular form of BIG’s design, “A Mosque for All,” is driven by a simple yet effective concept. The project derives its warped aesthetic through the accommodation of two significant axes: the city grid that conforms to Scanderbeg Square and the necessary orientation of the Mosque’s main wall to face Mecca. While the parapet and upper portions of the walls align to the street, the ground level twists to orient itself and the main plaza towards the Muslim Holy City. Thomas Christoffersen of BIG explains this key decision: “The alignment towards Mecca solves the dilemma inherent in the master plan: in its triangular layout the mosque was somehow tugged in the corner; now it sits at the end of the plaza, framed by its two neighbors. The resultant architecture evokes the curved domes and arches of traditional Islamic architecture, for both the mosque itself and the semi-domed spaces around it.”

A series of plazas result from the master plan’s layout and massing: two small plazas on either side of mosque and one large gathering space in front punctuated by a minaret. These plazas are arranged to help accommodate the large groups of worshippers during holy days while also providing compelling spaces for more secular daily use. The facades of the buildings are riddled with a fine pattern of small rectangular windows inspired by Islamic mashrabiya screens. This pattern of glazing coupled with the curving walls will allow for ever-changing light patterns within the worship hall.

BIG’s design is a success in its ability to address and merge a number of contextual and cultural concerns. As Mayor Rama noted: “The winning proposal was chosen for its ability to create an inviting public space flexible enough to accommodate daily users and large religious events, while harmonically connecting with the Scanderbeg square, the city of Tirana and its citizens across different religions.”

Finalist: seARCH, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Design Team: Bjarne Mastenbroek, Kathrin Hanf, Peter Veenstra

with Andrea Verdecchia, Pablo Domingo, Teresa Avella, Simona Schroder, Manuel Granados, Jose Rodriquez

Collaborators: Lola Landscape Architects, Daan Roosegaarde en Pieters Bouwetechniek

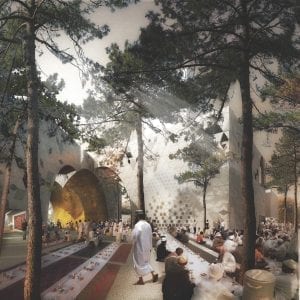

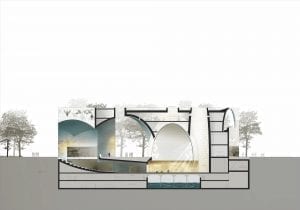

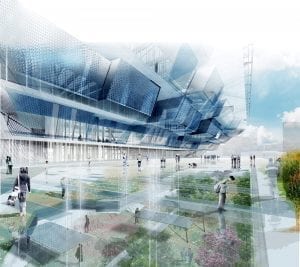

The entries of the finalists all contain varied and often compelling design solutions. Specifically aiming to avoid a “bird’s eye view” architectural solution in favor of the experiential, Amsterdam’s seARCH generated a design that reveals itself gradually but rewardingly. The museum for example, is a carefully designed journey. From the below grade lobby accessed from a sunken square, visitors take escalators towards the exhibition spaces housed in a dramatically cantilevered volume. There they are presented with a panoramic window that looks out over Scanderbeg Square.

The architecture of the mosque places a clear priority on the interior experience. Appearing as a stylized yet unassuming cube from the exterior street facades, the entrance approach from the partially sheltered main plaza reveals a series of shimmering, irregular domed ceilings carved out of the rectangular volumes. These domes, along with an interspersed grove of trees, give the plaza and mosque interior an intimate spatial quality despite the grand scale. While this inside-out approach does diminish the mosque’s external presence from certain street-side vantage points, seARCH’s entry offers one of the more spiritually intriguing worship spaces of the finalists.

Finalist: Zaha Hadid Architects, London

Design: Zaha Hadid with Patrik Schumacher

Project Directors: Viviana Muscettola, Michele Pasca di Magliano, Loreto Flores, Effie Kuan

Project Team: Alvin Triestanto, Philipp Ostermaier, Hee Seung Lee, Gerry Cruz, Xia Chun, Ergin Birinci, Santiago Fernandez Achury, Rochana Chaugule, Soomeen Hahm, Chung Wang, Kanop Mangklapruk, Luis Miguel Samanez, Alejandro Nieto

Collaborators: Grant Associates Landcape Architects, Buro Happold

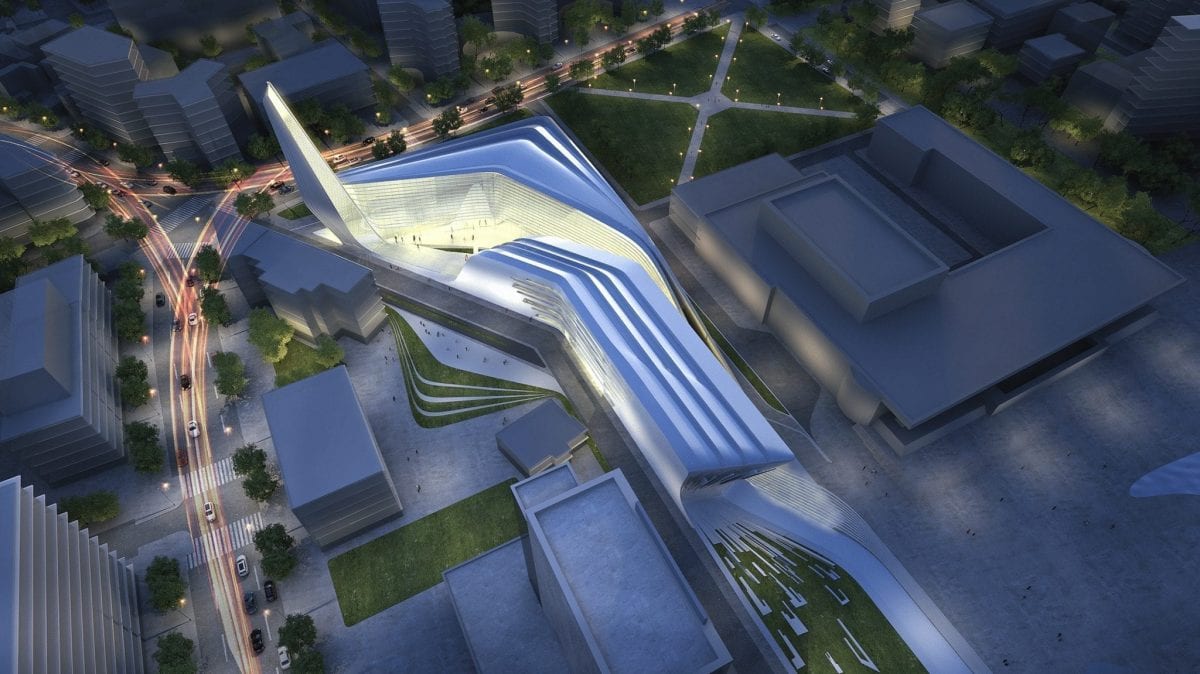

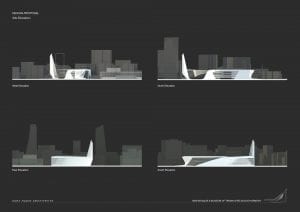

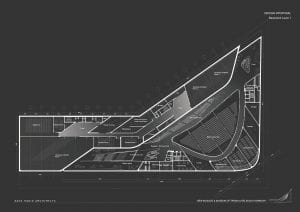

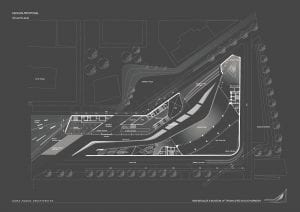

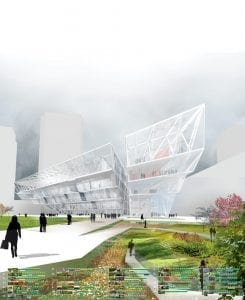

The complex imagined by Zaha Hadid Architects takes the form of two seamless masses wrapping around the site perimeter, gradually growing in height from the museum to the mosque and culminating in a towering minaret. This layout creates an internal courtyard, an “intimate valley, a secluded garden for art, meditation and civic life” that also gives access to both the mosque and the museum.

Images: ©Zaha Hadid Architects

The project, with its streamlined, curvilinear forms, bears the unmistakable aesthetic stamp of its renowned designer. In fact, Hadid even revisits one of her previous design concepts, the “urban carpet.” Utilized in Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Center, it is employed here on a grander scale, as the west façade of the museum folds outwards onto Scanderbeg Square, merging the two entities in a “Garden of Religious Harmony.” These familiar attributes, while well employed here, walk a fine line between effectively establishing an iconic landmark and merely applying the veneer of a famous architect’s brand – a risk that is understandably common to any architect with a strongly refined, internationally recognized aesthetic.

Finalist: Ortega/NEXO, Madrid

Design:

Andreas Perea Ortega

NEXO: Ivan Carbajosa Gonzalez, Lourdes Carretero Botran, Manuel Leira Carmena

Collaborators: P.E.Z.+Adriana Giralt Landscape Architects, Mecanismo (structral engineers), Valladares (engineers), Aurora Herrera (museum curator)

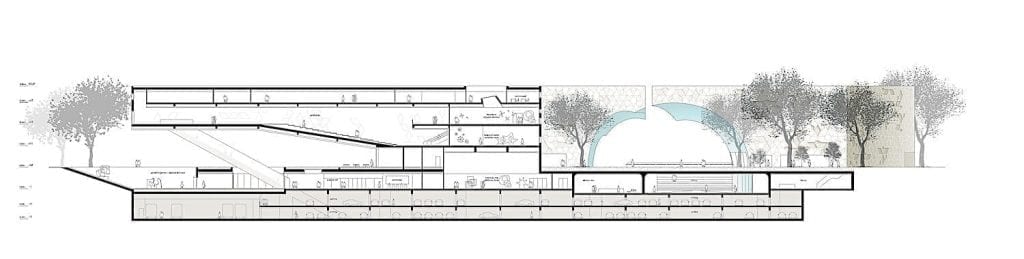

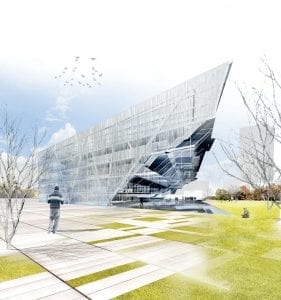

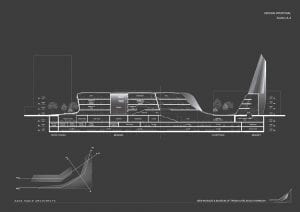

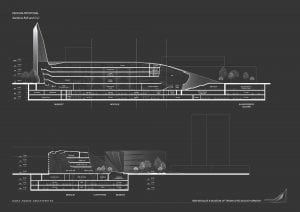

Seemingly in opposition to Hadid’s entry, the Ortega/NEXO team adopts a decidedly anti-style stance in an effort to “[transcend] those current architectural fashions that compete in a tiring parade of progressively more banal and puerile ‘floral floats.’” The team posits that architecture “is not a problem of representing space. It is not a case of solving architectural problems with rhetorical solutions or formal or technological special effects doomed to outdate.

With this position established, the team conceived a single volume cutting a strong diagonal across the site. In order to increase the volume of the public space, a large portion of the complex is lifted from the ground to create a partially sheltered plaza that features a sunken, glass-covered garden. Inside, the mosque’s vast prayer hall uses a system of tiers, oriented towards Mecca, that help gain the maximum amount of interior worship space with an efficiency that surpasses the schemes of the other finalists. The interior of the worship space eschews “anecdotic and obsolete” domes and other traditional Islamic signifiers for a more abstract spiritual space enveloped by slender roof beams and transparent roof filtering sunlight.

While this no-nonsense approach to avoiding the use of ephemeral, in-vogue styles is admirable, one wonders whether the overall result diminishes the experiential and emotional qualities of the worship hall. Although the interior of the mosque is a refreshing, light-filled, albeit universal-leaning space, the highly structural aesthetic of the exterior gives few recognizable clues to its sacred function, and presents a rather steely coldness that is arguably ill matched to the objectives of the competition.

Conclusion

While each of the finalists presented intriguing designs, the jury rightfully awarded BIG the commission for a careful consideration of urban, cultural, and religious context, an ability to create a unified, iconic piece, and, importantly, a grounded realism and practicality that will help ensure that the design can indeed be made reality. With BIG now preparing to enter the contract agreement phase of the project, there is hope that in a few years the city will possess not only a new mosque and museum, but a captivating piece of contemporary architecture that will help establish Tirana as a city of progress.