Bauhaus Director, Hannes Meyer, Rehabilitated with

the 2007 Restoration of his Winning Design

After the Nazi government ascended to power in 1933, one of their first acts was to take possession of a trade union school in the Berlin suburb of Bernau and turn it into a training facility for the SS and Gestapo. This action represented an antithesis of the school’s original purpose when it was built in 1930—to serve as a training facility for the members of the All-German Federal Trade Unions. Since the union movement was an anathema to the Nazis, it is understandable that this institution was a high-profile target on their agenda so soon after they took power. The fact that the architect of record was a Communist may also have played a role.

Initially, the Federal School of the All-German Trade Unions (ADGB in German), had been the subject of a competition in 1928, won by the new Director of the Bauhaus School in Dessau, Hannes Meyer, with his partner, Hans Wittwer. The team also included a supporting cast consisting of the architecture design department of the school and the Israeli architect, Arieh Sharon. Although this competition was hardly as high-profile as one which took place a couple of years earlier for the League of Nations Headquarters in Geneva—also entered by Meyer—it could hardly be characterized as one which slipped completely under the radar.

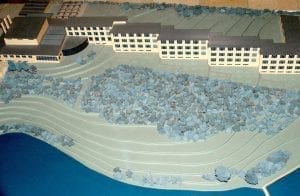

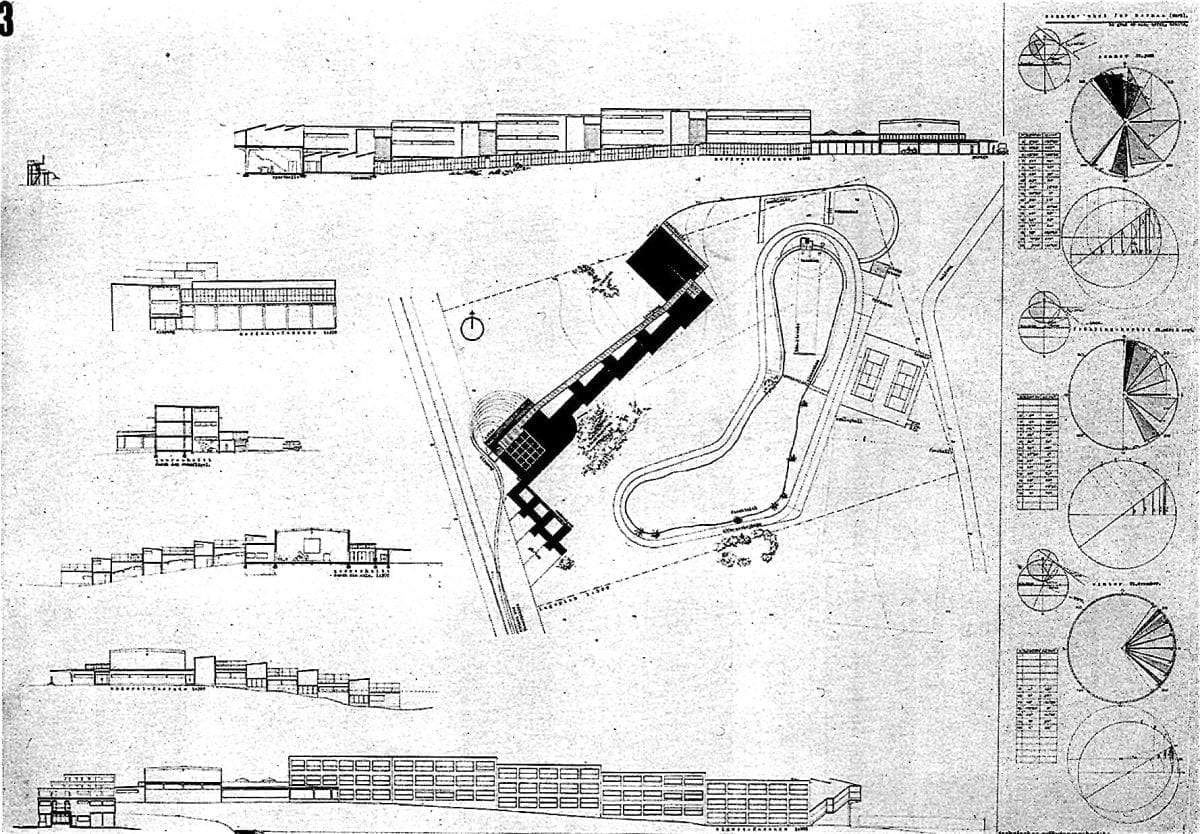

Aerial view of model from east; Bauhaus competition entry (right)

Why this competition was limited, rather than open to all architects was made clear by the program. Although it could have been limited for political and budgeting considerations, the list of shortlisted participants was an indication that the goal was to produce something modern, rather than traditional, and more in tune with the forward-looking philosophy and pedagogical Zeitgeist of the left.

Still, as an invited competition, some of the most important German architects of that era participated. In addition to Meyer, they included Max Taut, Eric Mendelsohn, Max Berg, Aloys Klement, and the lesser known, Wilhelm Ludewig. Meyer was supposedly included in the mix at the insistence of the architecture critic, Walter Behne, who was also on the jury. This presented Meyer with an opportunity to showcase the Bauhaus and, in particular, his guiding principles—the “New Objectivity” (Neue Sachlichkeit).

The ADGB competition was to serve Meyer as a proving ground for his design philosophy. In contrast to past German competitions, some of which dealt with the symbolic embellishment of state authority—the Reichstag competitions were prime examples—the social content of the ADGB competition was undeniably a major factor in the design. Sponsorship by the All-German Trade Union Federation was in itself an indication that imagery could well take a back seat to functionality, thus expressing working class ideals.

Circulation link from administration and dormitories to classrooms

Based on a point evaluation system, the jury placed Meyer far ahead of the other competitors with 62 points, Klement being second with 34, and Taut was in third with 29 points. Meyer opted for a linear configuration of the school, with a modular, repetitive composition of the dormitories anchored by the school’s functions at both ends—a block containing the administration, cafeteria and auditorium at the entrance, and classrooms and a gymnasium at the far end. Added to this were single dwellings for faculty on the entrance road.

In keeping with Meyer’s philosophy, which emphasized the creation of small learning groups, each dormitory block contained three floors, with ten students residing on each floor. Each block thus provided for a larger group of 30, resulting in a student capacity of 120 for the entire school.

Lobby exterior with interlocking glass at right; cafeteria interior with operable windows

But this was not just the building’s composition, which impressed the jury; they also rewarded the Bauhaus design for the attention it paid to the topography of the site. By arranging the modular composition along a descending slope, the building was able to embrace both the adjacent lake on the one side, while creating a sort of interior commons of the other. In doing so, the Bauhaus team combined the functional and topographical to form an impressive compositional whole. This was in stark contrast to the entries of Klement, Mendelsohn and Taut, which relied more on the strong image of the structure (große Form), rather than function.

The complex, which now serves as a trade school, has recently been renovated to its original condition. Although this was by most standards a low budget building, some of the fine detailing—interlocking glass blocks are one example—mark this as a Bauhaus project. One may assume this, even if the exterior bears little resemblance to the trademark Gropius-style buildings in Dessau.

Classroom and gymnasium complex

The ADGB did receive landmark status in 1977 when it was still in the possession of the East German regime (DDR). Still, it recent restoration has pumped new life into one of the more significant projects of its time. The question remains, why has the ADGB drawn so little attention, especially when many of the principles espoused by its founders have been accepted as guiding principles in our educational systems? It wasn’t part of MOMA’s International Style exhibition in 1932 (Meyer was mentioned), and despite its appearance in some European publications at the time of its completion, it generally has been ignored.

Meyer’s political affiliation with the Communist party and the subsequent Cold War may be one reason. After being pushed out of the directorship of the Bauhaus in 1930, Meyer went to the Soviet Union, where he practiced until leaving during the Stalin purges for Mexico in 1938. Moreover, old grudges die reluctantly: the German architects who immigrated to the U.S., such as Gropius, Breuer and Mies van der Rohe, were instrumental in downplaying Meyer’s importance in the modern movement. Added to this is the fact that Bernau was in the eastern sector of Berlin under communist rule until 1989, making it somewhat inaccessible for western visitors. Now all that has changed. This project, one of the most important competitions of the 1920s, can now be enjoyed by the world community.

Note: After this article was printed in the COMPETITIONS quarterly, the ADGB school received the initial 2008 World Monuments Prize, awarded by Knoll. Subsequently, it was designated a Word Heritage site by UNESCO in 2017.