Miami Performing Arts Center with Sears Tower in center; Competition (1995), Completion (2006)

COMPETITIONS: What was the first competition you participated in?

PELLI: I believe the first was during my third year in school as an undergraduate. It was a sketch competition for completed designs. It was run by Ernesto Rogers, an Italian architect (an uncle of Richard Rogers), who was teaching in Tucumán. I won it, and, as the first prize, he gave me Space, Time and Architecture, a book that I still have.

Petronis Towers (1992-1996) Photos and images courtesy Cesar Pelli Associates/Pelli Clarke Pelli

COMPETITIONS: There have recently been design competitions, which consist only of sketches. For instance, there was a sketch competition for the Getty, won by Machado and Silvetti. How do you feel about this kind of competition, which requires less work than a normal design competition?

PELLI: It depends how you look at it. In terms of effort and investment in time, money and energy, it’s very fair. The problem with a sketch competition is that it tends to exaggerate the problems of architectural competitions, particularly when architects judge them. What is being chosen is an image. Buildings are much, much more than images. Buildings have to fit a place, have to fit a function, have to be built within a certain budget. The sketch may be wonderful and lovely, but one may end up with the wrong building. I would never advise a client that is trying to select an architect to organize a sketch competition.

San Francisco Transbay Terminal- aerial view (left); upper level park view (above) – Images courtesy Pelli Clarke Pelli

San Francisco Transbay Terminal- Images courtesy Pelli Clarke Pelli

San Francisco Transbay Terminal – Competition (2007) Completion, Phase I (2017) Images courtesy Pelli Clarke Pelli

COMPETITIONS: Going back to your first competitions….

PELLI: The first competition I did after I came to the states was the Crane Competition…the firm that makes sinks for bathrooms, etc. I did not win first prize, but I won a second or third prize—$100. The subject was ‘a bathroom.’ Of course I have participated in many competitions since then. With some I have problems; but I enjoy the act of designing and competing.

COMPETITIONS: This ‘bathroom competition’ brings up the subject of how young architects gain access to the next level. Aren’t smaller competitions like this possibly the way for young architects to advance their careers?

PELLI: It’s the old fashioned way. Clearly the more operative today is for young architects to work with better-known architects—with the larger firms. They grow up within the firm, acquire experience, and acquire contacts. That’s how Bill Pedersen became an architect: the firm of Kohn Pedersen Fox did not start or grow by winning competitions. They grew by becoming well-informed architects within the context of other firms.

Today it is the prevailing path. The young architect who quickly opens his or her own firm, trying to get commissions on his or her own, is a remnant of the past. Architecture has become very complex; the act of producing suitable buildings requires a great deal of knowledge and experience. It is a poor way to learn it just by yourself, when you can learn it more efficiently from those that have done it before.

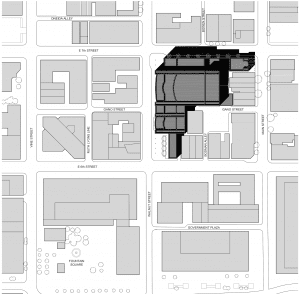

COMPETITIONS: Coming to your most recent winning competition, what was your first impression when you saw the site of the (Miami-Dade Performing Arts Center) competition?

PELLI: Tough! The first impression was: why did they ever choose this site? Second and third impressions were better, because I realized that the site has potential. A performing arts center in this place will be a first step in changing that whole area, renewing it, giving it life. Once I saw it like that, the site acquired strong, positive characteristics. Also, it straddles one of the most important avenues in Miami—Biscayne Boulevard. It’s good walking distance from downtown, although nobody in Miami would ever walk three blocks.

Miami PAC from bay (left) and Pedestrian bridge to Knight Concert Hall – photos: ©Robin Hill

Miami PAC Opera House lobby (left); Parker and Vann Thomson Plaza for the Arts (right) – photos: ©Robin Hill

Miami PAC Concert Hall lobby (left); interior (right) – photos: ©Robin Hill

COMPETITIONS: One of the problems with that site was the preservation question—the Sears building and tower. What did you decide to do with the tower? Did you move it?

PELLI: If you move the tower, you destroy it; so we left it where it was. The Sears Tower is not really a tower. It’s the corner of a building on top of which they put something that, together with a base, looks like a tower. It comes down to the ground on only two sides. And it is all stucco. So if the intention is to preserve, it’s not because it is such a fantastic piece of architecture; its value is primarily historical. It’s the first art deco building in a town where art deco later became important. You couldn’t preserve the whole building and build the performing arts center there too.

COMPETITIONS: I’m thinking of another project, which is almost complete—the Performing Arts Center in Cincinnati, where the site is also very constrained. It appears to be so tight that it is almost impossible to build there. When the site is so constrained, is your first task to sit down and see if you can even meet the program?

Aronoff Performing Arts Center, Cincinnati Photos and drawings courtesy Pelli Clarke Pelli

PELLI: Actually we looked at that problem even before we were engaged, and, in the interview, we showed how it could be solved. To me, that was the key. We knew it could be solved, and that it could be solved even better if they acquired a piece of land we recommended; and this they did. This was not so much to give space for the halls, but to allow maneuvering for semis (trailers) inside the block. Actually, the site ended up being an absolutely perfect site, because that allowed us to put the loading docks, and the usual ugly blank walls at the back of the theater, hidden from view on an existing alley. We tested it with a real interstate truck, and a good, experienced driver has no trouble negotiating it. So this will be a performing arts center with no backside.

COMPETITIONS: Miami is known for a certain style. Did you in any way try to take this into consideration?

PELLI: Naturally. I think the colors of the buildings in Miami are very important. It’s part of how one understands Miami. In Miami, people find two styles: art deco (Miami Beach), or what they call Mediterranean, and the cracker style. Both are not only characteristics of the styles, but are characteristics of any architecture. One of the things that architecture in Miami developed very well are color schemes that are fantastic against the deep blue skies of Miami. I made a point of just driving around and stopping and asking people, ‘which buildings do you like?’ I asked architects to tell me which buildings people in Miami like, even if you find them hideous. The architects just couldn’t think like that; they kept on telling me all of the best-designed buildings. But the people knew, and that is important, because if they are liked, that means that somehow they have connected with basic perceptions.

The most-liked buildings are usually quite profusely planted and with terraces. We have used all of this, using the good Miami colors, plantings, surfaces (stucco); so we have a design that has nothing to do with art deco or Mediterranean style, but will be a comfortable new member of the family, like some of the art-deco buildings that site right next to the Mediterranean buildings, whereas some do not.

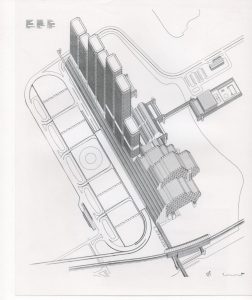

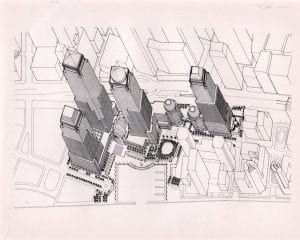

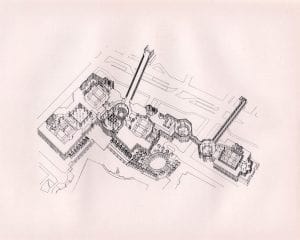

COMPETITIONS: From some of your early designs, like the United Nations Competition in Vienna to other more recent ones, including the house out west, which was recently shown in the New York Times Magazine, you have a strong linear organization—which isn’t terribly popular anymore.

UN City Vienna, Competition Finalist (1969)

PELLI: Not with architects; but people love it.

COMPETITIONS: Is this something you try to maintain to the extent possible?

PELLI: No, this is a preference. If it is applicable, I propose it, and if the clients like it, then I proceed. It’s not something that I try to impose. In smaller buildings, like the house, it was just a way of organizing a plan clearly, and they liked it. In larger projects, what a linear organization does for me is that it creates a place for meeting. If you do a grid, people move all over, and you may never run into a friend. On a single, central avenue—Main Street—you run into your friends. It increases the public aspect of a building.

COMPETITIONS: During a panel discussion after the Pritzker Awards ceremonies in Columbus, Indiana last summer (1994), which you took part in, the topic was ‘small cities,’ and you made the comment, ‘towns get built one building at a time.’ What did you mean by that?

PELLI: After all the planning, infrastructure, etc. takes place, what ultimately happens is that the town is built a building at a time. In talking to architects, what I try to do is remind the architects that theirs is the final step that gives character and shape to a place. And it has to be remembered that each building is a piece of the larger whole, which is a town.

University of Buffalo Medical School Competition Finalist (2012)

COMPETITIONS: Referring back to Columbus, the Commons, which is at least partially a mall…

PELLI: No, it is not a mall. There is a huge difference between a mall and a public space. The function of the mall is to bring people in to help sales. And everything is hierarchally structured to that purpose. What are important are sales. In the Commons of Columbus, the purpose is not that of a mall. It is owned by the City of Columbus and sales take a back seat to public events and programs. If people want to have a prom or exhibition there, and it adversely affects sales, they will have it anyway. A mall is exactly the opposite.

COMPETITIONS: When one thinks of the Commons, one thinks of Jean Tinguely’s sculpture. Did you designate the spot where that work was to go when you were in the process of designing the building?

PELLI: We had that spot for a piece of sculpture from the beginning. I convinced Mr. Miller to engage Jean Tinguely, and Chaos I happened.

I would like to comment more about the Miami (Carnival Performing Arts Center) competition. I think it was a very tough competition, very unfair to the participants, but on the other hand was one of the best-run competitions I have participated in—in terms of final results. Part of this competition was the 6-day charrette in Miami. Each one of us was given a hotel suite, one on top of each other, where we had continuous visits from every conceivable group from Miami, from preservationists, to advocacy groups, to children’s groups, representatives of every artistic groups, etc. We heard ideas and concerns from them all—property owners and neighbors. We worked continuously in this cauldron, which was very expensive, time-consuming, very demanding, but for the winner (not the losers) in the end, we wound up with a project that grew in response to all of those concerns, a project which, if it is a competition, one normally designs in isolation. And then the design may not do all of the things a good design should do.

My comment on this is that it would be wonderful if this could be repeated; but the architects would need to be compensated, for it is an extremely expensive process for the architects.* For the architects who do not win, it’s too much to ask. When we as architects enter competitions, we always have to invest a lot more than we are paid. In this case the difference was greater.

COMPETITIONS: If a way could be found to lighten the burden, would you be in favor of the charrette process?

PELLI: The important thing is not the charrette. The important thing is the interaction. However, I don’t think I would ever enter another competition like that unless the terms were very, very clear.

COMPETITIONS: What can we do about invited competitions to lighten the burden for the participants?

Sea Hawk Hotel and Convention Center, Fukuoka City, Japan (1995) Courtesy Pelli Clarke Pelli

PELLI: The most important thing to lighten the burden is to have very precise requirements. It would be important not to require levels of solutions of things that do not need to be resolved (at that stage). In Miami, for instance, because it was unspecified, we left block areas. We did a model drawing of a dressing room where there was room for twenty in the area. I notice that our competitors went to the trouble of working out every dressing room. Those things are very time-consuming. The difficulty often is that somebody ought to take the trouble to work out the geometries beforehand. Often this is not done, and things don’t fit. Nobody took the trouble of measuring the site plan. This happens often; it isn’t a rare thing. Openendedness, which sounds good, is the worst.

COMPETITIONS: When you find that you are to do an invited competition, do you allot a certain amount of time for this project? Do you block out a certain number of days or weeks and say, this is it and no more?

PELLI: It depends. We are trying to do that more and more. We set up the number of hours, the cost, and try to sty within that. We are getting much better at that—very close—not overrunning it by enormous amounts. In Miami, we couldn’t help it. Since I wanted it very badly, we decided not to keep tabs on it. We were just going to do whatever it took.*

*It should be noted here, that because of the later financial problems surrounding the construction of the project, Cesar Pelli voluntarily went ahead to complete the design work on the project without fee compensation—to make sure it was built to their specifications.

COMPETITIONS: Did the process in Miami boil down to politicians making the decision?

PELLI: No, not at all. There were really few politicians. There were people representing the County, i.e., Director of Planning, architects, etc., as civil servants. There were also people representing the performing arts, which I always find much better than architects. In the beginning there were architects who selected the competing architectural firms. The competitors are preselected by architects, and that was excellent. But once the competitors are preselected, I believe that the non-architects (as jurors) make better choices.

COMPETITIONS: Somebody who might be a user?

PELLI: Exactly. Users and people who have to pay for it might worry about cost, durability, function and appeal. Architects tend to choose purely on aesthetical preference.

COMPETITIONS: Not on organization?

Schuster Performing Arts Center, Dayton, Ohio (2003) photos: courtesy Pelli Clarke Pelli

PELLI: Very rarely, and only in schematic terms. I’ve never seen them take the time to see if something actually works. Our drawings were on display (in Miami), and all the users had time to see if our scheme really worked. An architect who is a modernist or deconstructivist will never select a post-modernist design, no matter how fantastically it responds to all the needs and vice versa. What was good (in the case of Miami) was that the architects remained as advisers to the jurors. They were part of the final presentation, and they gave their opinions. Also, the jurors had other experts advising them in planning, theater function, acoustics, and cost. I feel nervous when only architects judge.

COMPETITIONS: But couldn’t somebody turn this argument around and say, Cesar Pelli shouldn’t serve on a jury?

PELLI: Of course. But there are architects who have been very good. Charles Moore, for example, with whom I have been on three juries. I like to think that I am an open-minded juror, partly because my architecture does not depend on a constant aesthetic attitude. I try to see that a design responds best to a circumstance. Charlie was very good at that; but Charlie (Moore) was an exception. He had a very open mind, and it is amazing how few architects do.

COMPETITIONS: As far as the test of time, what projects have given you the most satisfaction?

PELLI: I am still very fond of the Commons of Columbus, my first public room. The World Trade Financial Center, the Winter Garden—that was a competition. Its presence has changed the character of Manhattan from one point of view and gives it a public value you can’t argue with. I believe that the World Trade Center towers look better now than they did before, just as two prisms sitting there. Now they don’t look so out-of-scale. They look like part of the overall composition. The World Financial Center helped to mediate between the World Trade Center and the smaller buildings. Before, there was no mediator.

World Financial Center, Battery Park City; Competition Winner (1980); Completion (1988)

World Financial Center, Battery Park City (Competition 1980; Completion 1988)

Photos courtesy Cesar Pelli Associates/Pelli Clark Pelli

COMPETITIONS: Sometimes a competition can open doors. What competitions were you in where another project followed as a result?

PELLI: The Vienna (United Nations) competition, which I did not win, was important to me, for I got the Tokyo Embassy as a result. Also, as a result of Bunker Hill (Los Angeles developer competition), I was included in the World Financial Center competition.

COMPETITIONS: How would you sum up your feelings about competitions?

PELLI: I still like them. They are an exciting way of working. It’s nice every once in a while to sort of test yourself against your friends, and very good at the end to see how somebody else solved the same problem—that there is not only one good solution.