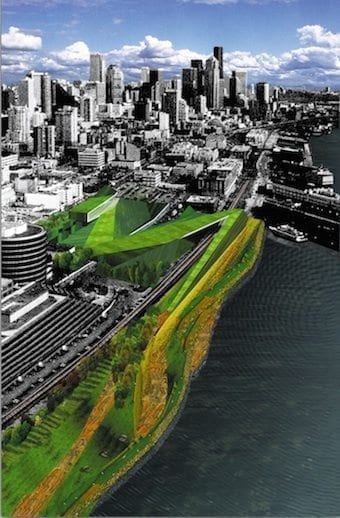

Seattle Olympia Park Sculpture Gardens – opening day (photo: Ben Benschneider)

COMPETITIONS: What were the main program challenges you had to solve in designing the Seattle Sculpture Park? The project is now in the development phase (2003); so has your approach changed somewhat, or are you sticking pretty much to your original plan?

WEISS: We invested an enormous amount of time exploring a number of strategies. We ultimately focused on a strategy of inventing an entirely new topography, wandering from the city to the water’s edge, over highway and train tracks. That proved to be a rather supple strategy. In fact, the current design right now is very much an elaboration of that scheme, but with a more richly developed palate, with landscape, urban, infra- structural, architectural, artistic agendas shaping it.

MANFREDI: The scheme was resilient enough, partially because the proposition of building a sculpture park in an urban setting had no models that we could fall back on. So we did look at a very large range of ways to envision the site. We talked to many artists and sculptors about what would constitute an interesting and dynamic sculpture park. A lot of adjustments went on prior to legally receiving the contract. But the scheme was ultimately able to undergo change without being radically different.

Original schematic proposal: Olympia Park Sculpture Gardens

WEISS: The strategy itself is incredibly simple on one level. The strategy can be drawn with one hand. That kind of clarity on one level has been able to accommodate a number of adjustments and change—the just right 20’6” clearance for the federal highway, the 23’6” clearance over the train tracks , etc; very approximate assumptions become more definite in development.

COMPETITIONS: To what extent do you want to be intrusive in designing this Seattle landscape, and to what extent do you want the sculpture in the landscape to do the talking?

MANFREDI: The thing about this site is that there is nothing natural there. It is actually a brownfield site, which has been excavated. What fascinates us is the opportunity to rethink what an artificial landscape might be; we don’t have the usual split between what is natural and what is artificial. This is all an artificial landscape within a very interesting city with topography, train tracks, a shoreline with boats—this is about as artificial as you can get. Everything is invented; so that kind of schism isn’t present on this site.

WEISS: In this case, one has to think of the landscape as a kind of partner for art. Here the surrounding itself is so much larger than the site with the views to the south of the city and the views to the north of the water and mountains. The site feels as large as the sound or as large as the city. We create a brand new topography, which navigates that forty-foot drop from the city to the water’s edge. If it were just a flat landscape, it would be a pretty uninteresting setting for art. So we have hyper-articulated the ups and the downs within certain areas, whereas the primary armature is very gentle over a slow path. If anything, we wanted to heighten the understanding of where it is highly topographically charged, and where it is neutral. So really it is both.

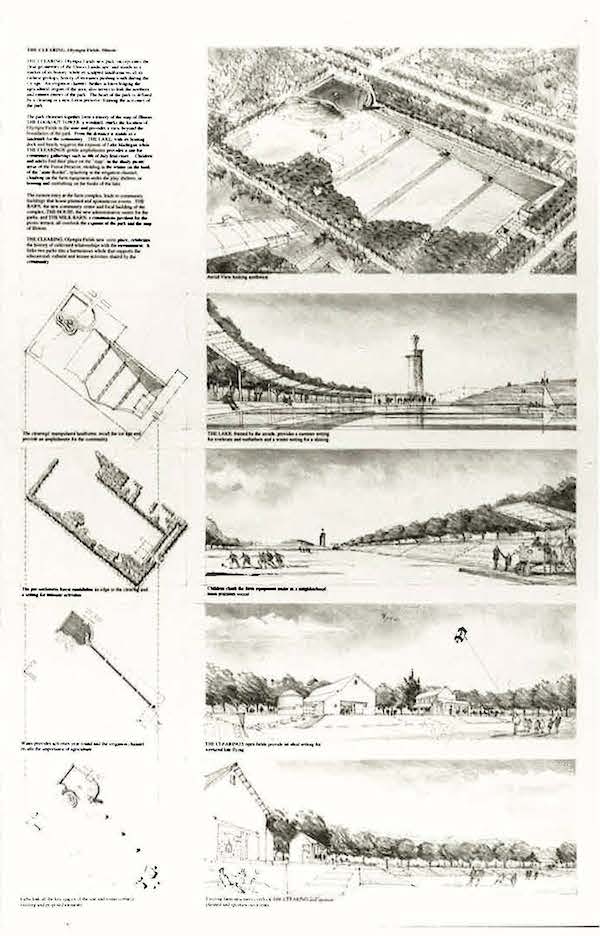

COMPETITIONS: The Olympia Fields Park competition was undoubtedly a milestone event, which opened a lot of doors for you. What prepared you for winning that competition?

MANFREDI: This sounds like a glib answer, but I think that a little naiveté helped. We always enter a competition with a little bit of innocence and a very high degree of optimism. Those are some of the virtues that still sustain us as we take on other competitions. If you have an optimistic frame of mind, you can be freer to propose solutions that you otherwise might be concerned about, given the program, site, or jury. You have to be somewhat fearless about that and have a certain amount of optimism and innocence.

WEISS: We actually initiated our practice by collaborating on a couple of pro bono projects in Harlem—one for a school community center, the other for low-income housing. I think what drew us together initially as architects was the conviction that architecture should be taking place in the public realm, where funding is so often elusive.

What prepared us to win may be harder to answer than what prepared us to enter

(Olympia Fields). What made that interesting was that it was asking how to create a center or a ‘there, there’ in an undifferentiated suburban landscape, a realm that didn’t have a common ground. The Olympia Fields project was clearly one which had a strategic budget. But they had very real resources to realize the client’s aspirations—to create a center where there had not been one for the community. It was interesting because it involved architecture and landscape; engineering and art.

MANFREDI: When you enter a competition, it has to ask the kind of question that is inherently fascinating. The competition for Olympia Fields asked not only social and formal questions, but posited the opportunity to explore a whole range of disciplines that are often segregated—like landscape architecture and ecology, architecture and civil engineering.

COMPETITIONS: The Olympia Fields site was very compact for a park. The space between the buildings on one end and the beginning of the terraced activities areas is separated by a depression in the landscape which leaves the viewer with the impression of the space being larger than it actually is. This is an old trick employed by landscape architects. Since you are both architects, not landscape architects; I wondered if this was a calculated gesture on your part?

The American Green – Olympia Fields Mitchell Park Competition board (courtesy: Weiss Manfredi Architects)

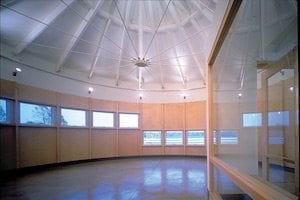

View to Mitchell Park entrance with meeting facilities (left) and administrative offices (right) Photo: Paul Warchol

WEISS: That touches on the observation that Michael made earlier about our frustration with these disciplinary boundaries—they’re really just administrative boundaries. Who is to say that a landscape architect might not have profound views about making architecture? Similarly, why shouldn’t an architect have views about what it takes to make a setting for architecture? Our background is such that we grew up in environments where the landscape was in many ways formative to our understanding of what we loved about architecture—Michael came from Italy, Rome to be precise; I grew up in northern California, in the apricot orchard district in the hills. In all cases the architecture was a participant, in a much larger landscape or setting, but never the sole presence. All of those have been about shaping settings as well as shaping buildings. You can say that it is the purview of the landscape architect in the traditional sense; but arguably, I think we have been keen on straddling a whole series of disciplines.

MANFREDI: Actually that device comes out of set design; so I suppose we should credit Italian 15th-century set design. To that extent all good ideas are in fact part of the public creative domain.

WEISS: We certainly were manipulating perspectives, and the manipulation of perspective is also an architectural agenda. So collapsing the scale of each of the terraces heightens the perceived expanse of the landscape.

COMPETITIONS: From winning a competition to realizing the final project is usually a long, complicated process with many adjustments along the way. Olympia Fields in its finished state is rather unusual in that it very much resembled your original competition scheme. How did that come about?

Pergola at far end of park (photo: Bruce Banlingen)

MANFREDI: Partly luck. Being a park, it was not subject to the intense pressures that might be the case where you have a large development. What really helped in Olympia Fields—as well as other projects—was that we spent a lot of time talking to the community as well as clients, explaining to them why our particular solution was the way it was. There were certainly a lot of minor adjustments. There was quiet period after winning the competition before we started work, where there was a grassroots campaign to explain why the design looked the way it did.

Community meeting room (Photo: Paul Warchol)

To some eyes it could appear a little surprising, different, unusual or even radical. It took some effort to explain the kind of geometries, inherent decisions—both programmatic and formal—so that, when construction started there was a sense that the community was a part of this effort.

WEISS: We do take budget seriously; so we had a professional cost estimator prepare budgets at the end of the conceptual design phase and the other milestones, like schematic design and design development. When the conceptual design was priced (for Olympia Fields), it was more than double their original budget. In fact, they had no flexibility with their budget. That became a critical moment where we had to ask: How can we achieve our core agenda? We had to understand what the primary agenda was, and what was secondary.

Originally there was a 20’ depression in the whole site. We were in fact able to achieve the impression of a great, excavated site, but it was ultimately only 9’ at its deepest point. Each of the terraces are back sloped, so that the berms themselves are 3’; but in fact the change in level from edge to edge is only 2’. So we enhanced and intensified the appearance of deep terraces, where it (the site) was actually quite shallow. We played all kinds of perspectival games once we understood the constraints. Similarly, we worked with very modest materials like a pressure-treated wood retaining wall, as opposed to stone. There was an enormous effort to remind ourselves what the overriding agenda was and figure out some strategic way to do it.

MANFREDI: For instance, the playing fields, which were always imagined as terraces for fairly passive recreation, were adjusted subtly so that they could be used for soccer and other organized sports. There were a lot of refinements which are the result of this evolutionary process.

COMPETITIONS: Because of the development of your careers, you seem to be participating mainly in invited competitions. Here the oral presentation becomes extremely important. You have both lectured and taught extensively. So I was wondering if that activity served you in making oral presentations to clients?

WEISS: Inevitably, if you really care about something, you are remarkably nervous about it, no matter how many times you have done it before. Before any one of our presentations, it comes down to being able to share the ideas with the level of passion and commitment we have brought to the design itself. We also try to bring to that presentation at least our understanding of what the aspirations are—or maybe a reinterpretation of what those aspirations might be. In the end, it’s not what you say, it’s the design.

Kent State University School of Architecture winning design (2013) Night view

Kent State University School of Architecture winning design (2013) Section

Kent State University School of Architecture winning design (2013) Aerial view

Kent State University School of Architecture winning design (2013) Functional diagram and interior perspective

COMPETITIONS: Do you gauge your presentation based on the composition of the jury—whether the majority are design professionals, or if it is loaded with lay persons?

MANFREDI: Never. Having been on the other side, as jury members, we found that we can never second-guess how the chemistry of a jury is going to work. You have to gauge how you present your ideas based on the material at hand. For sure, teaching is an important part of our professional lives to the extent that it has to do with communicating ideas; but I would have to agree with Marion that if you have enthusiasm and conviction about ideas, that tends to come through. Often, on the other side of the jury, we have seen incredibly sophisticated and skilled visual and verbal presentations, and they sometimes have backfired. They can come off as being glib and insincere, and I think juries do have a good antenna.

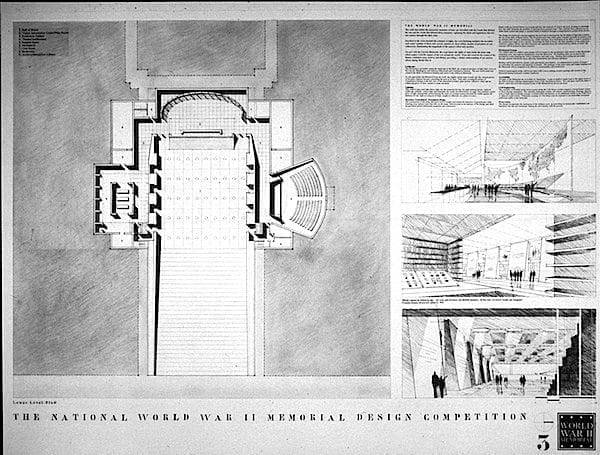

COMPETITIONS: After Olympia Fields, you were finalists in a number of 2-stage competitions, including the Women’s Memorial in Arlington and the WW II Memorial competition. Looking back, do you feel that much was gained by undertaking a 2nd stage?

World II Memorial Competition Finalist (1996) top: aerial perspective; bottom: diagrams and perspectives

MANFREDI: No. If you win a competition in the first stage, it’s about ideas. Often second stages are excuses to winnow ideas out on the basis of experience, team make-up, and other variables, which really shouldn’t be central to the competition. So I think we are a little wary of two-stage competitions.

WEISS: We were very fortunate to win the Women’s Memorial, which was a two-stage competition. In that case, it worked in our favor. I think two-stage competitions are often an abuse of architects. Enormous effort, care, joy, spirit, passion goes into a first stage; second-guessing and caution is brought to bear in the second stage. That is not what we do competitions for. Maybe you hire an architect at that point, because you want to begin the dialogue. You are halfway in and halfway out of bed with a two-stage event.

Competition for Women’s in Military Service Memorial and Education Center (1989-1987)

COMPETITIONS: You no doubt receive a lot of invitations to participate in invited competitions now. How do you decide which ones to participate in? What are the most important criteria? Juries?

MANFREDI: I think there must be a kind of visceral pull toward the kind of inherent questions the competition is asking. It’s an enormous emotional and financial expenditure, so if you can’t feel that kind of tug at that visceral level, then it is not worth it.

WEISS: You look at the jury to make sure it is a serious jury. If it is exclusively a local neighborhood group where critical criteria for decision-making is unclear, we not choose to participate. We do look for some level of rigor that should be established by the jury, and we’re old enough now that we don’t want to work on a competition that can’t be realized. We look for the funding, or the intention to get the funding. But the ‘visceral tug’ has to be there. There are some interesting competitions out there; but we don’t think we are the right ones to pursue them. If you were talking about doing the tallest high rise in the world, that would probably not be a competition we would enter.

Diana Center at Bernard College, New York (photos: Albert Večerka/Esto)

COMPETITIONS: University museums in some smaller college towns assume the role of the community museum (especially for educational purposes), in addition to acting as a teaching aid for departments. This is especially true when a viable permanent collection exists. Was anything like this envisaged for the new museum at Ithaca, or are we talking mainly about temporary exhibits?

MANFREDI: Yes on both counts. It’s unusual in the sense that there are no other natural history museums within a couple hundred miles. So it is a natural destination for a larger geographical area. In a more modest way, they already do community events where kids come and look for little “dinosaur eggs” at Easter. Where the Director very much wants this to be a place where you are introduced to important scientific research in an engaging way; the appeal has to be made at many different age groups.

COMPETITIONS: For architects with strong ideas about design, there is always the client who may want something more traditional…or more modern that you are comfortable with. Without getting into any specific cases, how do you approach this issue?

WEISS: A pretty common conversation that architects have among themselves is how to deal with clients who think they are interested in “modern,” but in fact are not. They are in fact interested in convention that looks modern. More challenging perhaps are those who think that a traditional language is the only language that can be spoken. I think we have been clear about our interest in seeing that buildings are of their time, that don’t have to depend on a language that has happened in the past. You can even argue that modernism is a very traditional language, too.

If we sense there is a clear agenda about style, and if it is a style that we think resides in superficial priorities, we like to better understand why this priority is critical. But if the client really wants something to have a certain particular look and style, we have in the past, suggested other architects that we thought might be more appropriate for them.

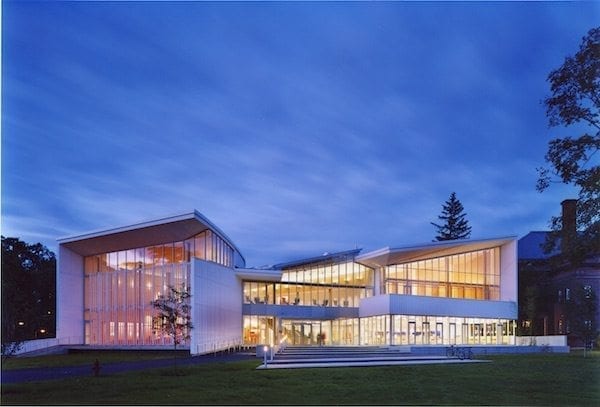

Smith College Student Center Model

Smith College Student Center winter scene (photo: Paul Warchol)

Smith College Student Center (photos: Jeff Goldberg/Esto)

MANFREDI: We are still relatively early in our careers; but we do have a series of built and unbuilt projects, so there is no need to really hide who we are. In an invited competition, you usually submit material prior to the selection; and we are very upfront about the kind of work we do.

COMPETITIONS: Many clients have unrealistic budget expectations when it comes to the incorporation of items into a budget. This usually leads to a lot of value engineering. How do you pick and choose? I.M Pei is quoted as saying, ‘You have to know which battles to fight.’

MANFREDI: If you start the project with a serious disconnect between what can be achieved and what the aspirations are, then it’s a very difficult battle. There is only so much creativity and ingenuity that you can bring to the table that can reconcile an impossibly small budget with a more complex set of aspirations. However, if a design is very strong and supple, it can in some cases be improved by the kind of editing processes you go through during a budgeting effort. It also can force the architect to be more careful about which parts of the design are essential and which parts actually form the heart of it—as opposed to other things that are less critical.

WEISS: Our interest is fundamentally about how little we need to build to achieve an agenda. That is a little bit different than ‘less is more,’ because ‘less is more’ might count on the $900 SF budget that might be associated to achieve the high level of craft that it sometimes requires. But if there are some strategic things that are imperative, they can sometimes hold up with a whole range of material expressions—if they are clear enough and strong enough. In our Seattle project, there are a few things that Michael and I have identified as ‘on the sword’ issues —where we would fall on the sword to keep. We can be more flexible on some others.

MANFREDI: As we start to build, we can appreciate more that some materials, which are inherently humble and prosaic and inexpensive, can actually be quite beautiful and rich, depending on how they are handled. This is often the case, more than with expensive materials.

University of Pennsylvania, Singh Center for Nanotechnology, Philadelphia, PA (photos: Albert Večerka/Esto)

COMPETITIONS: Some architecture firms, especially in Europe, find that doing competitions on a regular basis is quite a morale booster for everyone involved. What effect does doing a competition have on your office?

MANFREDI: I think I would agree that it helps (the energy level). But because we have a small office, I’m not sure that we can have a competition going all the time. One a year is probably enough for us. When we do, it gives us a chance to be fresh, be fearless, and think about ideas that we would otherwise not have the opportunity to explore in a short period of time.

WEISS: The Olympia Fields competition came at a time when we were very pressed with some really demanding projects. We were so burdened with administrative matters at the time that we needed to do something which was just about ideas.

MANFREDI: Likewise, the Seattle project also came along at a very busy time; but we were asked to think about architecture, landscape, infrastructure, art—something we had been waiting for for a long time. Everything wrapped up in one question on one site. It did lift the spirits of the whole office, and when you have an office as relatively small as ours, everyone participates.

WEISS: What was so great was that everyone was so interested in the question, and everyone was doing a different part of the research, whether it was stealth research concerning what the fisheries would say about removing the seawall or what the permitting requirements were for extending the site into the water. All this happened before we established a formal (design) direction.

Cornell Tech’s Roosevelt Island Campus Photos: ©Iwan Baan

COMPETITIONS: In spite of the traumatic events surrounding 9/11 at the World Trade Center, it did manage to focus people’s attention on architecture. People who never did that before are talking about architecture now. Is this just a blip, or are we, as a nation, thinking more about what we actually build?

WEISS: We’d like to think optimistically that it is raising the kind of visual literacy of the country in general. My fear is that it may be more about looking at it ten stories and up, as opposed to looking at it from the ground—even below ground—up. In the most optimistic sense, if you think about the fact that we have become more informed in the country about what good coffee is, what good food is, maybe we can start to think about what good cities mean. Certainly this event with the WTC has added a whole vocabulary which the general public has never had—about how cities are made.

MANFREDI: I suppose it is sad that it has taken an enormous tragedy for people to make that realization. But, if you look back historically, it’s always been the case. Except for the great fire, Chicago probably would not have initiated the kind of rebuilding, the kind of re-imagining it took to invent the skyscraper.