[do_widget id=search-2]

Interview: Peter Busby (Winter 2010)

COMPETITIONS: What led you to become an architect?

PB: I studied philosophy at the University of Toronto as part of my arts undergrad. In studying philosophy you study good and evil, right and wrong, laws and ethics. In the long run I decided philosophy was too sedentary, so I looked for a profession where I could live out some of what I had come to believe about right and wrong and essentially be able to do good. Architecture appealed to me as a place where I could affect the lives and futures of people in a non-political way. I also worked in construction to pay for the university—I did drywall—and got to know architects through that rather circuitous route, and talked to a few of them and went and visited some of their offices, and I took some introductory architecture courses in my final year of philosophy.

COMPETITIONS: You must have had people who influenced you greatly along the way.

PB: I credit one of the professors at UBC, Dr. Ray Cole. for awakening me to the environmental aspects of architectural design. At that point he was a 23-year-old PhD, a new professor at UBC fresh off the boat from England, and he had all these wonderful things to say about environmental issues and foreshadowing what everybody knows today about global warming. As best friends, we have mentored each other over the last 35 years and worked on some projects together.

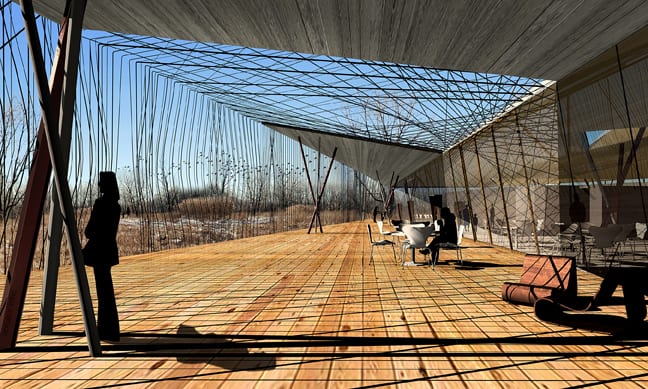

Brentwood Skytrain Station, Burnaby, BC

I took some of the knowledge from him and went off to Europe. At the time I graduated in 1977, work was pretty scarce in Canada due to a recession. So in 1979 I went to London, looked at Grimshaw’s work, Renzo’s work, and Foster’s work, and decided I wanted to work for Norman Foster, and spent three very great years at his office. He had a great effect on me. Of course he was interested in environmental issues at that time, and had just finished the Willis Faber, a very pioneering green building. Buckminster Fuller was in the office at that time doing some experimental work with Foster, and I got to meet and know him. Charles and Ray Eames were in and out of the office. It was a very interesting time to be there.

COMPETITIONS: Foster must have been a lot smaller in those days.

Interview: Jeanne Gang (Spring 2010)

COMPETITIONS: When did you decide to become an architect? Was it something you saw early on, or a personal connection?

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

JEANNE GANG: I always liked making things as a kid, rather than playing with pre-made toys. Not that as an architect you are actually building your own buildings, but it’s a profession that is related about putting things together, thinking how things work, making models, etc. While growing up on family trips, we looked at a lot of architecture, landscape and bridges. My dad was an engineer; so he always would go out of the way to go across some long bridge. One of the things that made a big impression on me was seeing the Indian native-American cliff dwellings in Mesa Verde, where landscape and architecture was kind of blended and so connected to culture. Also, being good at math and art was a good combination which led me into that.

COMPETITIONS: Maybe you don’t have to be good at math anymore to become an architect. Werner Sobek, Helmut Jahn’s engineering expert for many years, said that the students he had at Harvard were mainly interested in designing something, not necessarily how it would be put together — they could give that to somebody else to figure it out.

JG: Then why couldn’t just anyone be an architect? If you aren’t going to be connected to how it’s put together, then why go to school for so many years? Architecture is at its best when it is a synthesis of structure, materials, forms. If it’s missing one of those things, it’s dropping down a notch.

COMPETITIONS: After finishing your studies at the University of Illinois and Harvard, you worked in the office of OMA in the Netherlands. This wasn’t your first stay in Europe. So I’m wondering what you took from those experiences?

Interview: Craig Hartman FAIA of SOM (Spring 2000)

View from rooftop of San Francisco Airport International Terminal View to skylights from terminal interior

COMPETITIONS: What led you to the study of architecture?

HARTMAN: It wasn't so much architecture, as what architecture is about. When I was a kid I loved to draw and paint, loved science and, to a certain extent, math. Growing up in the sixties, when NASA was in the news, I was probably one of the millions who thought that space and science was the greatest thing. So I did all these science fairs and was even invited to some schools which had engineering programs. When I saw what it was actually about—the curriculum—it seemed very dry to me, not nearly as exciting as I had imagined it to be. My father was absolutely adamant that I not become an artist. At about that time one of my cousins, who was taking a course on architecture in college, came home. I saw the work and felt it was really interesting stuff. Initially to me architecture as an idea was more the pieces which made up architecture rather than the excitement of designing buildings. In fact, my understanding of architecture as a kid in Indiana was that of an arcane profession—certainly not cutting edge. When I discovered through one of my teachers that Ball State University had just undertaken the first architecture program in the state, I felt I should check it out, especially since our family finances precluded my going to an out-or-state school. It turned out to be an incredibly great experience.

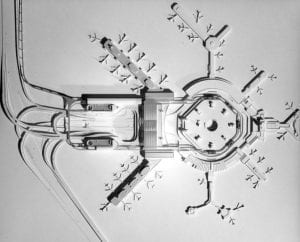

San Francisco Terminal: vehicle approach to airside (above, left); plan (above, right) and structural concept (below)

COMPETITIONS: That was still when the program was based in quonset huts?

HARTMAN: It was. And those were great times. The school was all in one place, and I believe that students often learn as much from one another as they do from faculty. We had some very energized young faculty there at the time, and that was a huge part of it. Tony Costello, for instance, was a huge influence on me.

COMPETITIONS: It was a great experiment.