[do_widget id=search-2]

Interview: Matthias Sauerbruch of Sauerbruch Hutton (Spring 2008)

GSW Competition, Berlin Winner Police and Fire Station, Berlin (competiiton 2002, completion 2004)

COMPETITIONS: Many architecture firms today have a multinational composition, and Sauerbruch Hutton is no exception. You started out in London, but moved to Berlin in 1993. Can I assume that was because you won a big competition here, then decided to stay?

MATTHIAS SAUERBRUCH: We started the office in London because Louisa and I met and got our BA in London. We then worked in offices in London, and basically through a number of circumstances decided to set up our own office. During that time we did a number of competitions on the continent, because in Britain there were hardly any competitions, whereas in Germany there were all of these big building projects which were competitions. One of the first competitions we entered, we won (GSE Headquarters Building, Berlin). We discovered fairly soon that there was no chance of actually realizing this project unless we were there. The other reason was that Berlin was really the most interesting place in Europe at that time. It just seemed it would be a missed opportunity not to be part of that. Once we started to set up an office, with all the infrastructure, and all the people attached, it becomes slightly less mobile. The irony is that for some years now we have not had any work in Berlin; it’s all elsewhere. But it is a nice place to be.

COMPETITIONS: In this day and age, with communications as they are, you can be almost anyplace

Interview: John Ronan (Winter 2008/2009)

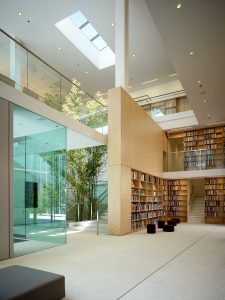

Poetry Foundation, Chicago Photos: Hedrich-Blessing

COMPETITIONS: You received an undergraduate degree at the University of Michigan; but it was not purely in architecture. When did it become apparent to you that you wanted to become an architect?

JOHN RONAN: Third grade. I remember writing a paper in fifth grade about 'Why I wanted to be an architect.' So I knew pretty early on. I always played with those lego-type logs as a kid, and in grade school I was always drawing little plans of houses. In high school I took four years of mechanical drawing, two of those years being somewhat architecturally based. So by the time I went to college, I knew that was what I wanted to do. Michigan's architectural program is basically two years of liberal arts and two years of architectural with a Bachelor of Science degree. Then you go on to graduate school for your professional degree.

Gary Comer Youth Center, Chicago, IL

Interview: Andrzej Bulanda (Summer 2008)

|

|

COMPETITIONS: When did you decide you wanted to become an architect, and who were some of the main influences for you?

Andrzej Bulanda: I have been thinking about architecture for a long time, although I didn't start in architecture. There was some family history and I was always interested in this type of work. Also, in those days in Poland, it was the only profession in which you could frame your own (non-political) agenda, and not have to be part of a large office. You could do small competitions, small projects.

I spent one year at GSD as a Visiting Scholar and wrote a book which was an interview with professor Jerzy Sołtan concerning his personal history with Le Corbusier, everything related to architecture, and the roots of his own life. From GSD Harvard, I got my position at Penn State University, where i taught for a year. Then I came back to Europe, to France, where I was working with Groupe 6 in Grenoble for two years on projects related to health and culture. In 1991, I started the firm here in Poland with my partner — we had met at the university in Warsaw.

COMPETITIONS: When you were working in France, those were the days when a lot of open competitions were being staged.

Interview: Richard Francis-Jones (Spring 2009) with Michael Dulin

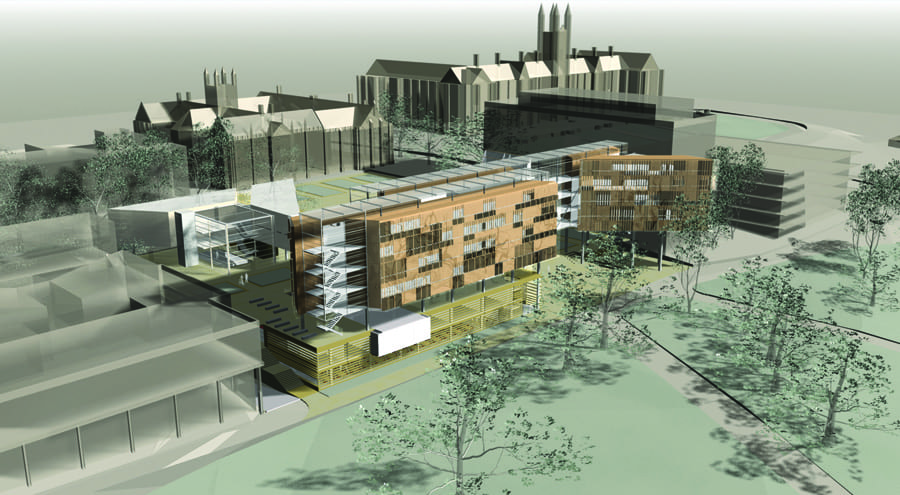

COMPETITIONS: The new University of Sydney Law School competition, which you won, included a lot of high profile architects besides FJMT: Neilsen Neilsen & Neilsen (Denmark), Axel Shultzes (Berlin), Norman Foster (London), (Bligh Voller Neild (Sydney, Aus), and Donovan Hill & Wilson (Brisbane, Aus). I assume it was invited?

Richard Francis-Jones: The University of Sydney became quite ambitious around this time and implemented a campus planning program called 2010. It included three major new buildings, the largest being the law school. The law school is currently downtown, so the competition was part of bringing the law school back to campus. The law school has a very prestigious faculty and the new site on campus is very strategic. It’s right across from some of the older neo-gothic sandstone buildings, and there’s a sense that it’s very solid. The building was to include a variety of programs and quarters for the faculty, and it also incorporates a law library and lots of general teaching spaces. But the main component is the law school. As a big competition, they had advisors from the architectural side – and the jury included James Weirick, Chris Johnson, Tom Heneghan from U of Sydney (all professors). It was a completely open submission of interest, worldwide. It was reduced to just a few teams and we had to assemble a very detailed – but short – submission for the second phase. We were limited to a certain number of pages and it had to include an interpretive program and outline what we were thinking about the site.

COMPETITIONS: Like a narrative of some sort?

RFJ: A narrative and a sketch – but only a few pages. Based on those submissions, they selected teams for the competitions (There were several competitions held simultaneously – the law school was just one). Then there was a full competition, and the interesting thing for me — and the unique aspect to this competition — was that we submitted our material, which included panels, a model, etc., and they were put on public display. The public could go have a look for about a month or so prior, and then we each made our design presentations to the jury. But it was also open to the public.

COMPETITIONS: So there was the proper jury but also the public?

Interview: Peter Schaudt (Fall 2008)

|

|

Peter Schaudt

Winner, Nathan Philips Square International Design Competition, 2007

Rome Prize Winner in Landscape Architecture (FAAR), American Academy in Rome Fellowship, 1990-1991 Third Place, Kent State May 4 Memorial National Design Competition, 1986 Citation of Merit, Innovations in Housing National Design Competition, 1986 Second Place, Copley Square National Design Competition (4 person team), 1984 Meritorious Award, Vietnam Veterans Memorial National Design Competition, 1981 |

COMPETITIONS: Environment often plays a role in what we choose to do with our lives. What was the determining factor that led you to become a landscape architect?

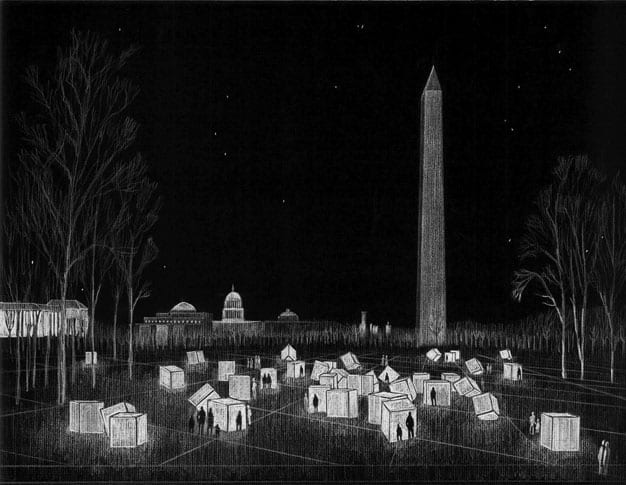

PETER SCHAUDT: My first goal was to become an architect. As I studied architecture here (in Chicago) at UIC, I was exposed to the great park system legacy of Chicago. We had many studios in the parks here. What actually led me to become a landscape architect was the Vietnam War Memorial Competition. I needed an art credit in architecture school, so rather than taking color theory or painting, and after seeing the poster, I approached the dean. He told me I could do it; ‘but you have to do it without an architect.’ So I teamed up with Charles Wilson, a wonderful sculptor at UIC, and I looked at that park through the eyes of a sculptor as opposed to an architect. The site in constitution gardens was a rolling site — very difficult because the competition site was half of an amoeba shape. That’s why Maya Lin’s project is so amazing. It’s because she was able to tie (her design) into the context.

Interview: Jacques Ferrier (Fall 2009) with Olha Romaniuk

Cite de la Voile Eric Tabarly, Lorient, France, 2007 - Winning competition entry (Photo: Luc Boegly)

COMPETITIONS: What inspired you to start your career in architecture?

Jacques Ferrier: First and foremost, I was fascinated with the way buildings were built, with their structure. Before I was trained as an architect, I was trained as an engineer - in science and mathematics - and then I pursued architecture. When I began my architectural studies in architecture, I realized the specificity of it, as compared to art or engineering. In a way architecture is less complex because there might be less calculation involved, but more complex because you work directly with people, with site contexts, etcetera.

COMPETITIONS: And what inspired you to start your own firm?

JF: I started a firm with a friend of mine who went to school with me. We started in 1990, as sort of a first run. I opened my own office in 1993, sixteen years ago now. We were lucky because it was the end of the golden age of public competitions in France and it was possible, even if you were a young architect, to be invited to participate in these competitions. When I started my practice, I managed to get invited to one such competition for a university laboratory building. With this building, I received a national prize, which was typically awarded for an architect’s first work. A few weeks after that, I won another competition for an industrial facility for the city of Paris – a water treatment plant. It was interesting because the brief for the building was very typical, but the lasting impact was on the site as a whole.

COMPETITIONS: Who were your mentors when you were receiving your education and who were your major influences along the way?

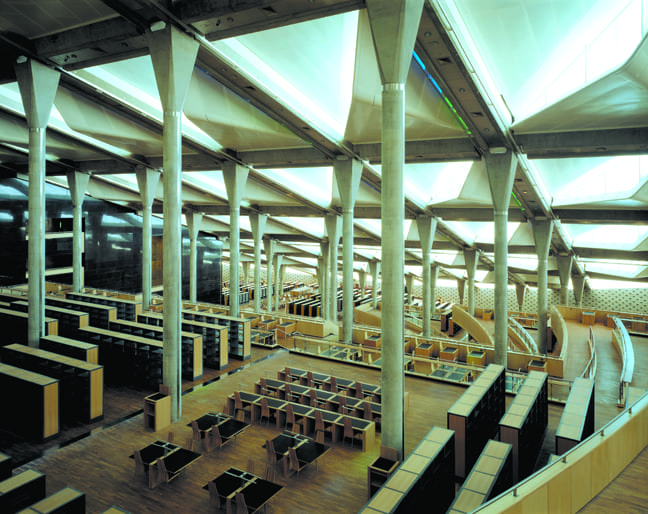

Interview: Allison Williams (Summer 2009)

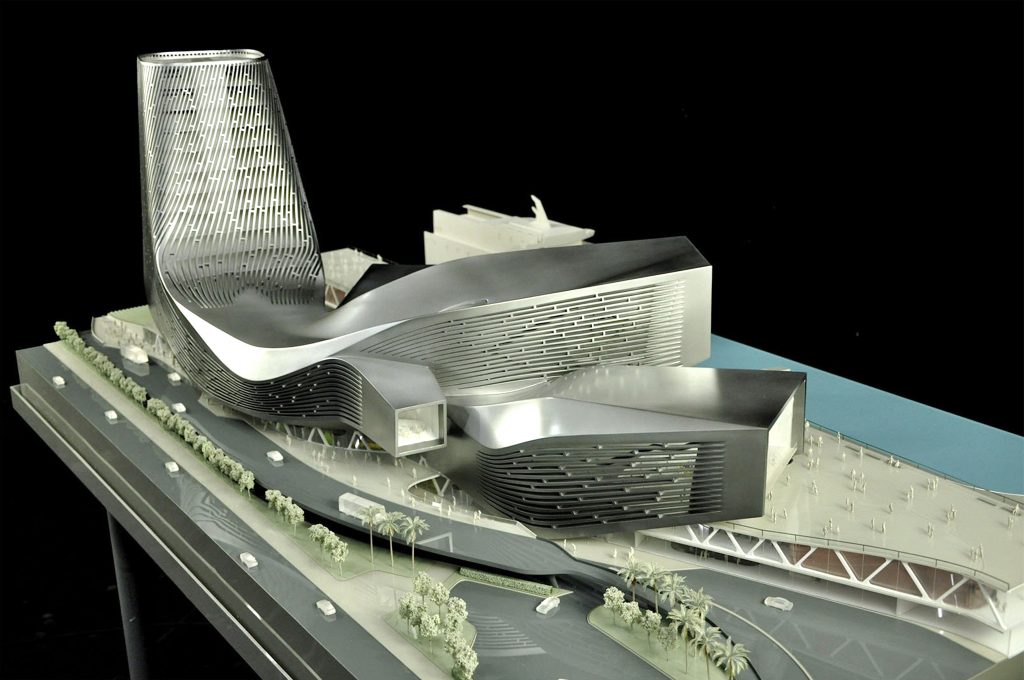

August Wilson Center for African American Culture, Pittsburgh, PA (Competition 2003, competion 2009)

AW: When I started there, I was the only one in my class of thirty who knew how to draw or knew how to express things. We had all kinds of backgrounds in the masters program at Berkeley, psychologists, structural engineers—you name it in terms of their background. They were very unfamiliar with the tools of architectural or life drawing.

COMPETITIONS: Was there a particular person or persons along the way who helped shape your ideas on architecture?

AW: Beyond my father, there were some inspirational people. People who really taught me the most are those who think of architecture as series of problems you need to solve. Gerry McCue, who later became the dean at Harvard was one. If I was going to identify the most inspirational architect, it would be Le Corbusier. I don’t know if it’s just a generational thing, or just total admiration. It probably has more to do with more time in Paris and France than any place other than places I have lived. I have probably visited almost every work by Corbusier.

During my time at Skidmore, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention Marc Goldstein, who was an incredible mentor. I benefitted in my experience and success at the office because of working with him. When he became ill, he looked to me to just take it and run.

COMPETITIONS: What was the first competition you ever entered? And the most memorable?

Interview: Blostein/Overly Architects (Summer 2010)

COMPETITIONS: What led both of you to architecture? Was it something that occurred early on, or was it more of an evolutionary process?

BETH BLOSTEIN: Our answers will be very different. My interest was pretty sudden. I randomly decided to take an architecture class at Ohio State, and once I got into it, it seemed to be such a natural fit—for a way of thinking and making things. Even though it wasn’t something I had considered before, it seemed pretty natural.

Beth Blostein and Bart Overly

Interview: Diana Balmori (Winter 2009/2010)

COMPETITIONS: What brought you to landscape architecture in the first place. And whom did you first look to as a model?

COMPETITIONS: When one sees your body of work, which are significant for the number of competitions you have participated in, one might assume that you are located in Europe, rather than in this country. It would appear that much of your work has come as the result of competitions. How did you get so deeply involved in that area?

DB: At one level, it’s the only way for a person who comes in from the outside for getting jobs. You’re starting an office, so where do you go to? I didn’t have any connections to say, ‘Give me a job.’ So from the beginning I jumped into competitions from day one, and I have pursued them very actively. Now we get into invited competitions and more direct commissions.

COMPETITIONS: Along the way, you must have learned something from these competitions.

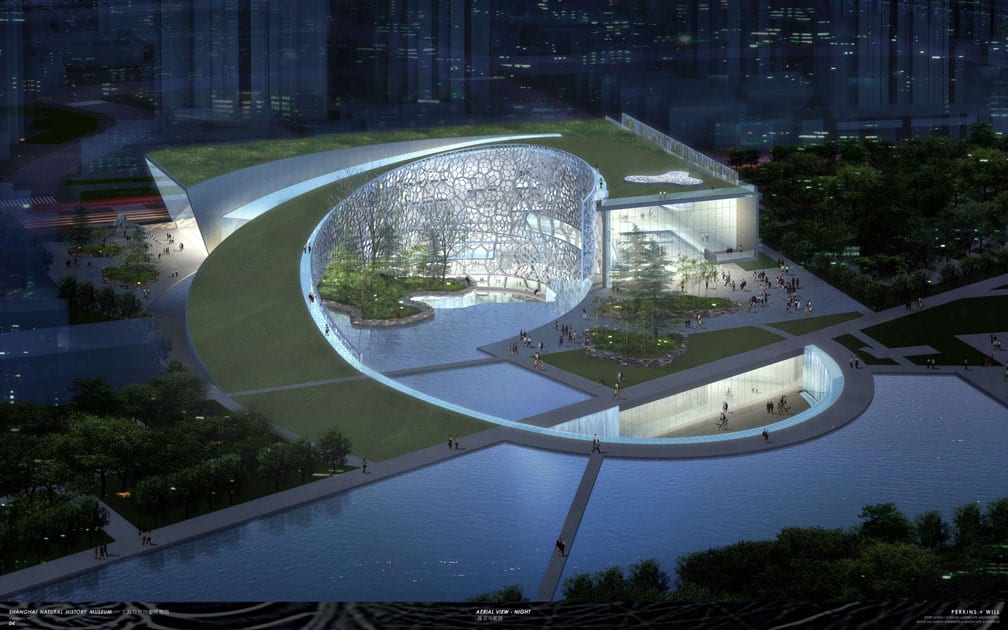

Interview: Craig Dykers/Snøhetta (Fall 2006)

COMPETITIONS: When did you decide you wanted to become an architect?

Craig Dykers: I started off wanting to work with fashion—women’s fashion and clothing seemed very interesting to me. I quickly learned that the world of fashion wasn’t what I had anticipated. It came to feel very superficial and calculating. I left that and was somehow accepted into medical school, perhaps because of an interest I had in the human body. My grades were not very high; but my notebooks were apparently impressive. In medical school your notebooks are reviewed as well as taking tests My ability to draw anatomical forms was very good and one of the professors recommended that instead of studying medicine I should enroll in the art school and become an anatomical illustrator.

I was confused with what to do with this conundrum. He advised me further, ‘You like science and art; architecture seems like a good thing.' I admitted that I had no idea what that was all about. He said something like, “Architects make churches and things like that. I felt I could work with this, making places for people. The architecture school accepted me and I rolled right into it, staying up many nights to work on my studio assignments. The end result of that long story is that there is an interest in the human form and the notion of the human body as it relates to the things we create. I think that is still with me.

COMPETITIONS: Was Charles Moore already in Austin when you were a student there?

CD: He arrived as I was leaving and there was only one semester overlap. I remember asking him why the nice parts of cities often appear to be on the west or north sides. Not entirely true, but it’s pretty frequent.

COMPETITIONS: Snøhetta’s origin began with the Alexandria competition. How did that come about?