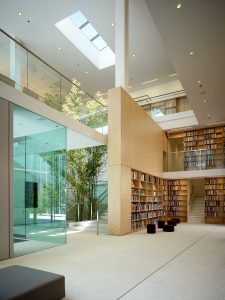

Poetry Foundation, Chicago Photos: Hedrich-Blessing

COMPETITIONS: You received an undergraduate degree at the University of Michigan; but it was not purely in architecture. When did it become apparent to you that you wanted to become an architect?

JOHN RONAN: Third grade. I remember writing a paper in fifth grade about ‘Why I wanted to be an architect.’ So I knew pretty early on. I always played with those lego-type logs as a kid, and in grade school I was always drawing little plans of houses. In high school I took four years of mechanical drawing, two of those years being somewhat architecturally based. So by the time I went to college, I knew that was what I wanted to do. Michigan’s architectural program is basically two years of liberal arts and two years of architectural with a Bachelor of Science degree. Then you go on to graduate school for your professional degree.

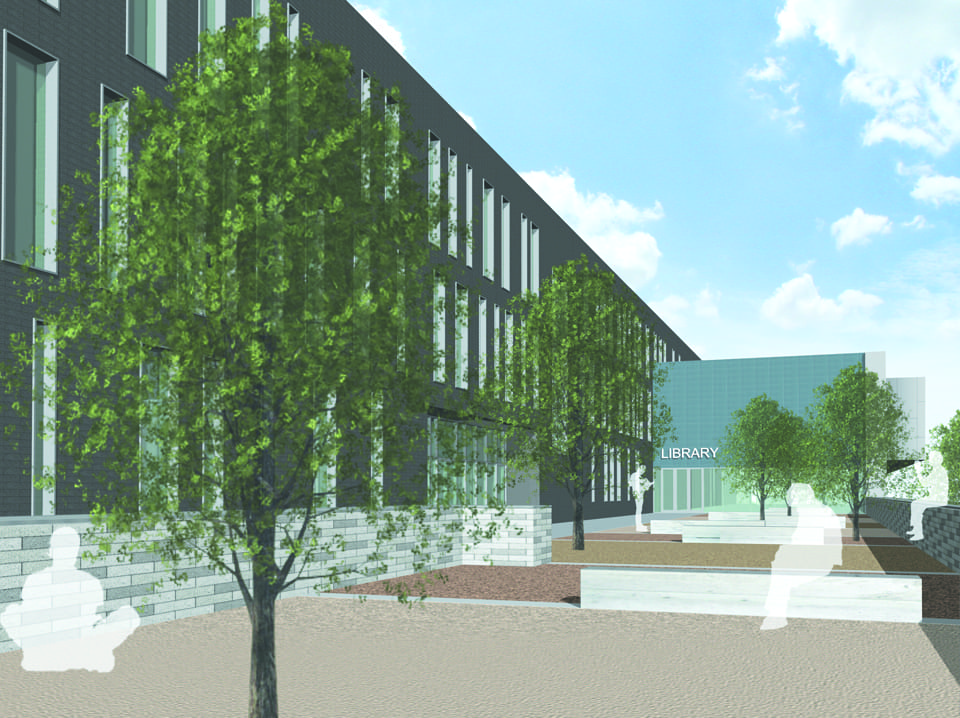

Gary Comer Youth Center, Chicago, IL

JR: Since I always intended to do that, it was an easy decision. A contractor had given my name to somebody about doing a large apartment house, so I thought maybe that was the right time. I was 33 at the time.

COMPETITIONS: While you were with Lohan Associates, you worked on some large projects. Has having that on your resume helped to convince clients that you can deal with projects of that magnitude?

JR: No, because for the first four or five years I was doing only small projects, and they were residential and interiors. So they were no help, because I was being hired to deal with a very different scale.

COMPETITIONS: So was it word of mouth that kept the residential practice going?

JR: Yes. Also, I started doing showrooms in the Merchandise Mart, and people saw and liked those. So the interiors and residential were mostly word of mouth. After a while when I built up a portfolio and started to become known, people start coming to you because they’ve seen your work. This is the best way because there is already an affinity there.

COMPETITIONS: What was the first competition you ever did?

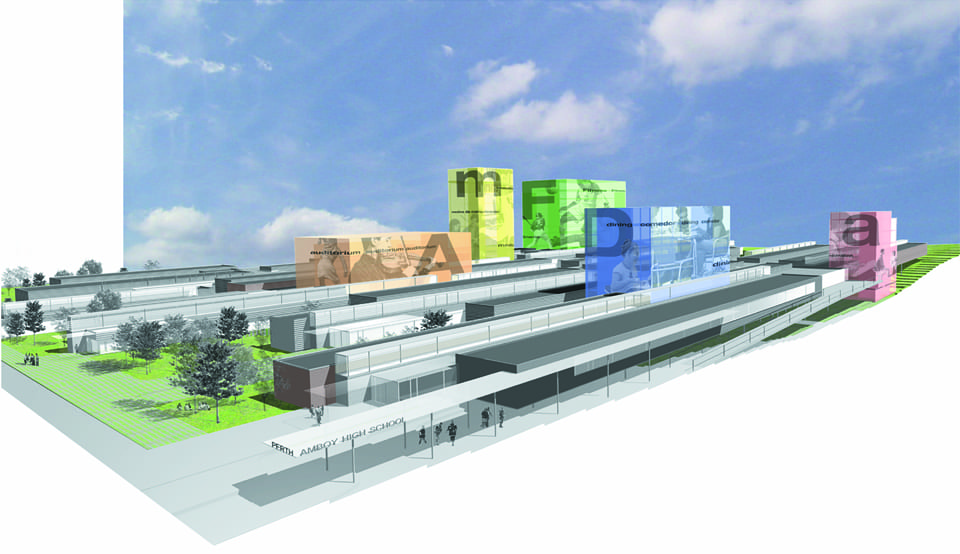

JR: I’ve only done five, and I’ve won three of them since I started my firm in 1997. The first was a Town House Competition by the Graham Foundation. We won a competition to do a building in Washington, which was an invited competition. Later we won the Perth Amboy High School Competition. But Europe has more buildings done by competitions with higher quality juries. I wish there were more competitions in the States coming along that were worth doing – like Perth Amboy. It was really well-run with a good jury; so you knew that they were going to pick a good project. They don’t come along that often; so I haven’t done one lately.

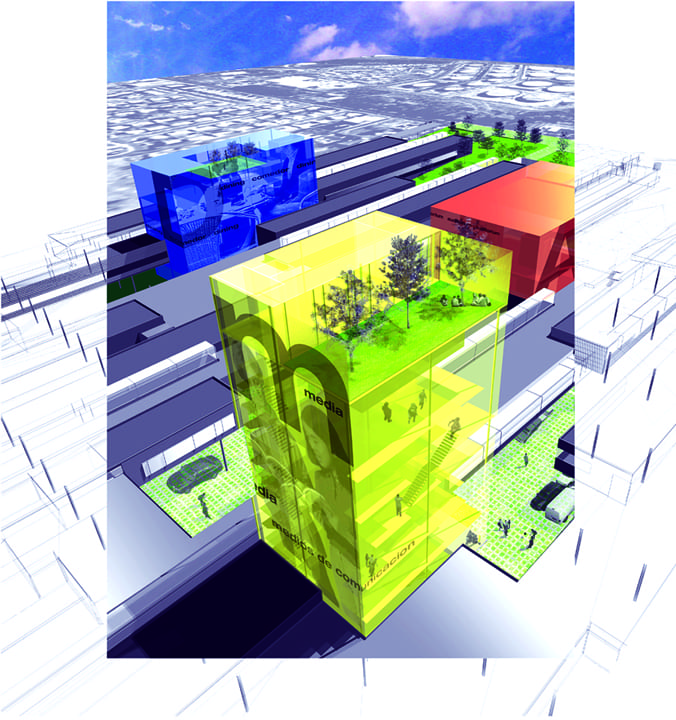

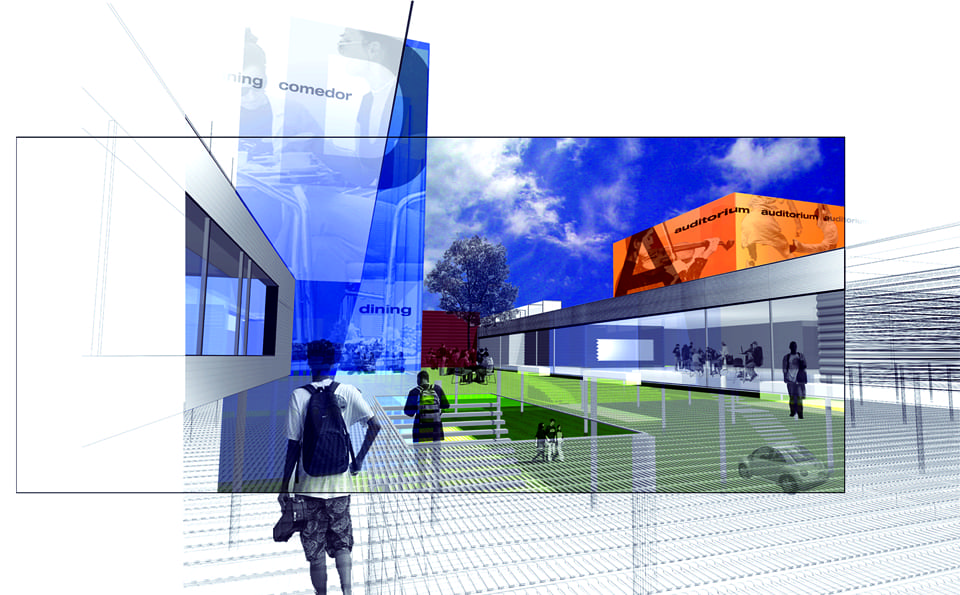

Perth Amboy High School Competition, Perth Amboy, New Jersey (Winning Entry, 2003)

COMPETITIONS: Winning a big competition can always serve as a milestone in one’s career, even if they aren’t built. In the case of some other Chicago architects —Helmut Jahn, Ralph Johnson and Jeanne Gang come to mind — it certainly fast-tracked them to bigger and better things. What effect has your win of the Perth Amboy High School competition had in terms of exposure?

JR: It did in that it got my name known on a national and international level. It was a very big, well-run competition with a quality jury and a real project. So a lot of well-known architects entered. Because of the competition with finalists such as Eisenman, Morphosis, and Fox and Fowle, it does increase your prestige. It was helpful putting me on the map. It did become difficult because the project didn’t start immediately, and it made it hard to get work actually: it was so well publicized that people would say, ‘He’s doing this huge school, and he doesn’t have time to do our project.’ So it was kind of a double-edged sword. Clients suddenly didn’t think their project would be the center of your attention.

COMPETITIONS: When many small firms start out, they do single family dwellings more or less out of necessity, and that seems to have been the path you followed. But isn’t it useful to deal with the site and organizational requirements of smaller projects. Students often are dealing with larger projects in their studios, even without worrying too much about structural details.

COMPETITIONS: It’s still done a lot.

JR: Especially with computers, because to people on the screen it all looks small. Computers have only exacerbated this issue of scale.

COMPETITIONS: You have been teaching at IIT for over 15 years. Have student horizons broadened over that period? I’m thinking of the connection between landscape and building as an integral solution.

JR: There are certain themes that students are interested in now that are different, such as sustainability, or ways in which the landscape interfaces with architecture — and of course the use of computer technology. Students are now very facile with images, and design is becoming very image-based. What was better when I started was that students were actually sitting down and figuring out how something was designed, figuring out a plan, or designing a façade. Now it’s just too easy to just cut and paste images together. There’s that nitty gritty of learning how to actually design something that is missing today.

COMPETITIONS: I understand that Werner Sobek, the German architect/ engineer, after teaching at Harvard, complained that American students are only interested in designing objects without caring that much about designing the building structurally. They feel they can just design the exterior and leave the structural details up to somebody else.

JR: An architect from Harvard applied here for a job last year. As I was going through his portfolio, I asked him, ‘What material is this?’

A: “I don’t know. It might be metal.”

Q: “What’s the structure? Is it concrete or steel?”

A: “It could be concrete; it could be steel.”

At least at IIT, the student would have to know what the structure and system is. I think that varies from school to school. I think Sobek is right; I don’t think that rigor is there anymore. And the media is partly to blame. What they choose to put forward is usually object buildings, usually big gestural buildings. There doesn’t seem to be a value system within the media for well-designed buildings that aren’t spectacles. So the message that students get is that everything should be a spectacle. So architecture is devolving into a form of entertainment. It is somewhat resistant to that because of the whole history it has behind it. When I go to other schools and sit in on reviews, it’s very much an image-based type of structure. There is very much more to architecture than just peddling images. Students who are in their early twenties are very impressionable, so they kind of take their cues from these images.

COMPETITIONS: I notice you are teaching material investigation seminars at IIT. It would appear that new materials-especially those concerned with sustainability-are appearing on the market on almost a daily basis. How difficult is it to track the usefulness and durability of so many new products?

COMPETITIONS: Yesterday it was announced that the city of Chicago was expecting a windfall by privatizing Midway Airport. A lot of people have already indicated how they think this money might be used. What are the city’s highest priorities at the moment-both in the short- and long-term?

COMPETITIONS: We are entering uncertain times economically. I assume that a lot of present students of architecture will be going ahead with masters degrees rather than attempting to enter what promises to be a difficult market in the profession at this juncture. During the last slow period in the early 90s, firms like Kevin Roche were going to four-day weeks, just to avoid layoffs. How do you see the immediate future here?

JR: In my office it’s mostly people in their early thirties or late twenties; so they’ve never really seen a recession. They’ve only seen the good times. So there is going to be a wake-up call in the profession. I graduated from Harvard in 1991, and that was at the bottom of a recession, and I think I was one of the few people in my class who was working in an architecture office a year after we graduated. It’s very possible we may see those times again.

What I hope doesn’t happen is what happened last time, which is that a lot of people got out of the profession. Times were so bad that they went out and found something else. As a result, there was a big gap a few years later: there was nobody with 5-7 years experience. A person like that was hard to find. The profession has to figure out how we keep from losing those people. The difference now may be that this is now a global situation. In our case, about half of our projects are outside of our area – either in other parts of this country or the world. To a certain extent that mitigates the bumps in the economy.