with Mike Dulin

COMPETITIONS: The new University of Sydney Law School competition, which you won, included a lot of high profile architects besides FJMT: Neilsen Neilsen & Neilsen (Denmark), Axel Shultzes (Berlin), Norman Foster (London), (Bligh Voller Neild (Sydney, Aus), and Donovan Hill & Wilson (Brisbane, Aus). I assume it was invited?

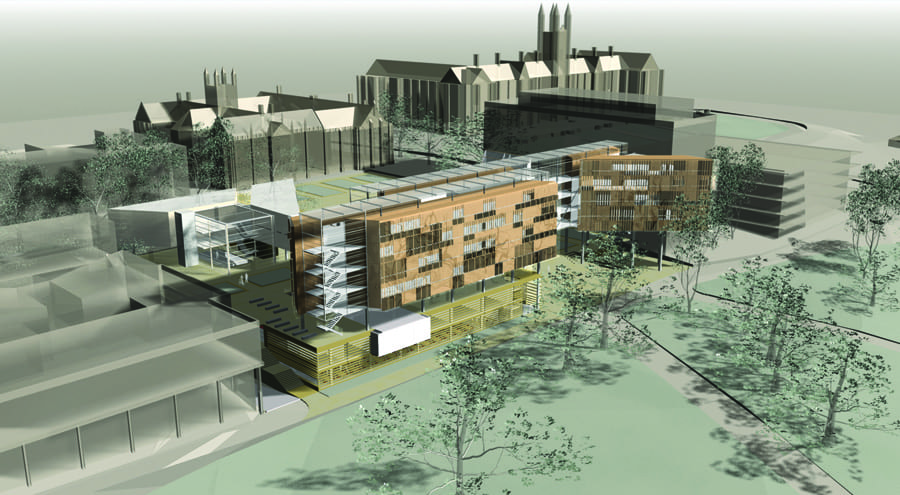

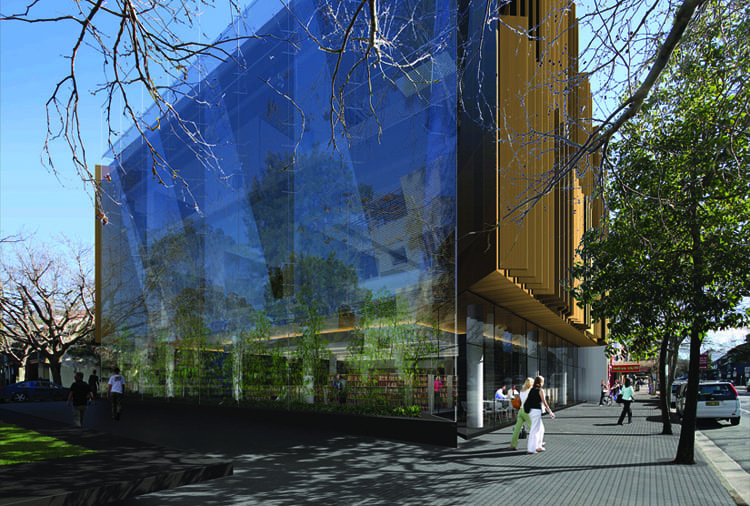

Richard Francis-Jones: The University of Sydney became quite ambitious around this time and implemented a campus planning program called 2010. It included three major new buildings, the largest being the law school. The law school is currently downtown, so the competition was part of bringing the law school back to campus. The law school has a very prestigious faculty and the new site on campus is very strategic. It’s right across from some of the older neo-gothic sandstone buildings, and there’s a sense that it’s very solid. The building was to include a variety of programs and quarters for the faculty, and it also incorporates a law library and lots of general teaching spaces. But the main component is the law school. As a big competition, they had advisors from the architectural side – and the jury included James Weirick, Chris Johnson, Tom Heneghan from U of Sydney (all professors). It was a completely open submission of interest, worldwide. It was reduced to just a few teams and we had to assemble a very detailed – but short – submission for the second phase. We were limited to a certain number of pages and it had to include an interpretive program and outline what we were thinking about the site.

COMPETITIONS: Like a narrative of some sort?

RFJ: A narrative and a sketch – but only a few pages. Based on those submissions, they selected teams for the competitions (There were several competitions held simultaneously – the law school was just one). Then there was a full competition, and the interesting thing for me — and the unique aspect to this competition — was that we submitted our material, which included panels, a model, etc., and they were put on public display. The public could go have a look for about a month or so prior, and then we each made our design presentations to the jury. But it was also open to the public.

COMPETITIONS: So there was the proper jury but also the public?

RFJ: There were architects from around town, students and of course, your competitors. All six were done in one day — 3 before lunch and 3 after lunch.

COMPETITIONS: Who was the jury?

RFJ: James Weirick, Chris Johnson and Tom Heneghan. Good jury. James W is a professor at UNSW and he’s very articulate – very good. Hennigan is terrific, too. Chris Johnson was the one mostly responsible for making this a more public process. What was interesting about this is that we’ve gone from a country that didn’t always support architectural competitions to one that really does. But this process was unique — to make such a public presentation and to be presenting to your competitors.

COMPETITIONS: That’s somewhat of a departure from most competitions.

RFJ: Yes. Usually, you’re in a locked room with a jury and about 25 advisors. You might meet your competitors in the lobby or something, but you never see them present their work. Here, though, all the work had been exhibited beforehand and interestingly enough, we saw how our competitors presented ideas about the same project. We presented second and it was interesting to see what some of the people that presented later in the day did. Some might make oblique references to other projects presented earlier, but this is the only competition where I‘ve seen that opportunity.

COMPETITIONS: It’s like the peer review that never gets to happen.

RFJ: Yes. One of the things about competitions is that the work isn’t always exhibited properly or gets out to the public. This was actually the reverse: the work was out in the public first and then presented to the expert jury.

COMPETITIONS: Does the culture — the general public that is — have a fairly keen sense of design? Like what works, etc?

RFJ: There is definitely an interest, and these sorts of things definitely promote that. Like this one here (the MCA building) – specifically the second international competition. There was tremendous public interest, but the presentations were all “closed-door” and then months passed before we heard who’d won. Of course what they’d done is selected the winner and were working with them on public presentations. Then they had a huge exposition in the museum where the scheme was presented in the main space. In the gallery they also showed the other entrants’ submissions. It was a huge exposition, and there was a lot of public interest. But that’s rare. The interest is there, but it depends whether you can feed it or not. A lot of institutions can get a bit worried about that, because it can turn into a PR disaster. In a sense the trouble with displaying the other schemes – from their point of view – if the public doesn’t support the administration’s decision then they’re in trouble. But that’s what making public buildings is about: it should be in the public domain. If you don’t get their support, you’ve got a problem.

COMPETITIONS: It sounds like the law school competition was successful in that regard.

RFJ: It was successful and to my knowledge it hasn’t been repeated in this country.

COMPETITIONS: The MCA format is more of the standard.

RFJ: Yes, and they kept the display set up in the foyer. The completion was more below the radar. With two failed competitions, I imagine it would be harder to make it as public.

COMPETITIONS: What kinds of competitions and for what kinds of buildings do you do most of?

RFJ: It’s mostly public buildings

COMPETITIONS: Are they similar to the law school competition format?

RFJ: It varies, but it’s [usually based on] an overall expression of interest, and we submit our credentials or we’ll be invited. There’ll be some vetting process, which gets down to a shortlist of 12 or so — then maybe another shortlist down to around 5 to do the competition. They’re quite common processes for university buildings, where the vast majority of our buildings have been done like that. One interesting thing in this city — which is again somewhat unique — is that we had a mayor here named Frank Sartore. He was an independent in the early 90s who was really very interested in the quality of design. We had a situation where a lot of the major buildings in the city were being done by a relatively small group of architectural practices that are generally more commercial in focus. He and others were dissatisfied with the quality of these buildings — they were major private buildings that were having a big impact on the city. So he introduced new legislation that required developers of sites over a certain dimension and buildings of a certain height (45 meters) to be the subject of architectural competitions. It still applies to developers building in Sydney. I think it’s an amazing thing that the city has done, and I don’t know of another city that’s done anything like this.

COMPETITIONS: The late Senator Patrick Moynihan had a similar interest in improving design in public buildings — for federal buildings, at least. He developed a program that fundamentally changed the way they managed the procurement of designers for federal or GSA work.

RFJ: I think when you’re the government or a university you can do that. I think the first university to introduce competitions in Australia was the University of New South Wales under John Niland. At the time, Glenn Murcutt was on the campus advisory committee. That really began this process of designing buildings through competitions, and it was enormously successful. The campus of UNSW — it’s a small campus — was the second university in NSW so it didn’t have all the sandstone and it had the reputation for being an uglier campus. In ten years it’s been completely transformed, and now it’s actually a beautiful campus. It was a strategic objective the Vice Chancellor had: he knew it was a huge weakness for the campus, and his [focus] was on increased remote learning — it actually increases the importance of the campus experience. So he invested a lot into it and Glenn Murcutt and others on the advisory committee gave him independent advice. So again, it became very design- and competition-focused. We and others were able to benefit from that.

COMPETITIONS: Quite a coincidence – with the city and the schools doing this around the same time.

RFJ: Yes, the competitions at the campus pre-dated the competitions the mayor (Santore) rolled out. It’s one thing if you’re the vice chancellor and you decide that since they’re your buildings that you are going to pay for, you will require this (competition) process. But when the city makes that decision, it’s quite different. For example, let’s say you own a piece of land and you want to put a new building up. You can’t choose your architect, you have to have a competition. I think it’s worded in a way so it’s not so restrictive and there are other ways to meet the requirements (without the competition); but the alternatives are quite expensive. It’s in the developers’ interest to do competitions — in fact they’d be crazy not to. When you’re involved in this process, the city shares the stakes – which is incredibly enlightened when you think about it.

COMPETITIONS: Aren’t the architects ultimately responsible for the character of the city?

RFJ: That’s right. And it does introduce a public character to the process. And you know, the mayor – Frank Sartore – was definitely visionary in that respect, and his vision has been carried on and supported.

COMPETITIONS: It sounds like it was also very popular with the public, but maybe not the developers?

RFJ: Not right away, but over time the developers started to see it as pretty fantastic.

COMPETITIONS: It levels the playing field a bit.

RFJ: And it also creates more of a collaboration between the city and the developers and raises the level of discussion. Of course, what they soon realized is that it improves the development opportunities. It’s not an either/or situation. Once you get the city involved — everyone’s involved — you get a better architect, you get a better building. I do think the publication and the exhibition of the competition outputs that the city has hosted maybe isn’t always as good as it could be. So some of that follow-through could be good. Nevertheless, the results have been amazing. One of our early competitions, for example, was for an office tower. We were part of a small group that was invited — big names. It was incredible that we were able to get on the list. We were a bit of an oddity, and I think they tried to pull out a younger firm to mix it up a bit. And to be honest, that’s a bit less likely to happen in a traditional procurement system. So we got invited to participate — and we won.

COMPETITIONS: What’s the name of that building?

RFJ: Castle Ray Place. The building hasn’t been built yet; but it looks like it’s actually about to start. We’ve had other competitions here that have got good results, but it’s also lifted the stakes a little bit. Design excellence and the competition process are seen as very connected — maybe not always — but nevertheless competitions have become a central part of doing business.

COMPETITIONS: It’s a great way to showcase local talent, too.

RFJ: While Sydney has always been a very global and open city, especially since the Olympics, the competition process has thrown open the international door. Most of the competitions we do include locals (Australians) and internationals as well.

COMPETITIONS: So when did you first decide to pursue architecture? Was it early on – like in high school?

RFJ: A little bit. When I was in school, the program consisted of a three year degree plus one travel year and a two year completion. I actually took two years out, which made it a bit longer. In terms of why I studied architecture, though, let’s see. When I was in high school I didn’t really know what I wanted to do – like most kids – so I took a lot of high-level math and science courses. Not because I particularly liked those subjects – I really liked history and arts – but there was this whole notion that if you’re serious or if you were still unclear, the math and sciences were the most enabling areas to study. So of course when I finished school I thought, “I really don’t want to do that again.” I came out knowing what I didn’t want to do – I wanted to go to University to learn more and study and I didn’t want to do those subjects. I wanted instead to get back to those other things that I enjoyed. Architecture just kind of surfaced at that point. I went to the enrollment day and asked just one question – “is there going to be any chemistry classes?” to which they said no. I actually traveled to the United States during that time and I became interested in Frank Lloyd Wright’s work – and I saw vast amounts of it. At that point I caught the bug and when I returned I knew. I think at some point in architecture you become very passionate about it – you just get it. You really feel the incredible strength of a work of architecture and the effect it can have on you. Generally, when you get that bug, you’re never going to lose it. From that moment on I was very passionate about it. It wasn’t something I did for any other reason than the pleasure of doing it.

COMPETITIONS: That was before you went back to Columbia (University)?

RFJ: What happened was – I came back to Sydney and finished school and applied for some jobs and grants, one of which I won. It was an American company, actually, ITT – every country they had a business interest in they sponsored a student from that country to study in the states. That year they gave out 25 grants around the world and then gave 25 grants in the US and they got us all together in NY. All the people who’d won this fellowship all went to NY for a few days – from all fields – we had a great time.

COMPETITIONS: When was that?

RFJ: Around 1986 or 1987, which is when I went to Columbia. I went to Columbia because I just loved NYC; and I still do. You experience that city and you can’t fail but react to it. So I wanted to go back and spend time there. Of course, Columbia is a great university and Kenneth Frampton was chairman at the time, and I was quite interested in his work.

COMPETITIONS: How was that relationship? I understand you studied under him and then later taught with him.

RFJ: It was fantastic. I have enormous admiration for Frampton. He’s occupied an incredible position for a sustained period of time – often under great stress and difficulty – but has shown enormous consistency and integrity. As a teacher, he’s someone of incredible dedication.

COMPETITIONS: How did his critical work impact your work – especially coming back here?

RFJ: He had an enormous influence on me. I have to say, the American architecture education and American schools, especially the ivy-league schools, are very high-level and super intense. It was a great experience. I got an enormous amount out of it. You get the opportunity to connect in some way with some major figures and Frampton was one of those for me. He was someone who’s work I felt a great deal of empathy for – and interest in – and that’s continued to be the case. I still talk to him and see him every time I’m in NY.

COMPETITIONS: Great tour guide when you go to NY, too.

RFJ: Oh yes. But I think for an architect who’s interested in the academy, you’re always in and out of it. I do have this position at UNSW as a visiting professor and I really enjoy spending time there. It’s difficult if you have a passion about architecture, you love reading about it, seeing works of high quality – particularly by your compatriots – it’s very inspiring. So it’s natural to spend time in the academy. It’s also interesting that the competition process – particularly with things like the law school – is the closest simulation to the final jury critique. You know – like the big one – where suddenly everyone’s there. I participated in the world architecture festival, which had that same quality of the final critique with people presenting projects. But the great thing about the competition was of course, everyone was on a very level playing field. Everyone’s got the same amount of time, made the same proposition for the same site, etc. Anyway, I love spending time in architecture schools, but don’t spend as much time as I’d like to.

COMPETITIONS: You know for the longest time – it’s maybe not as true anymore – but the competition was really something experienced more by American students. It was not nearly as prevalent in the outside “working world” as it was in school. It was the professionals – the faculty – that were aligned with certain schools that bought the attention to the competitions. In my experience, the students that did the most competitions throughout school continue to do them today and keep them on their standard operating schedule.

RFJ: Right. When I was a recent graduate I did a number or competitions – as many as I possibly could – and they’re great exercises. It’s good to be able to have that process as an integrated part of your professional life and while that type of work might be kind of expected, but you do need the society and structures to come around to those views.

COMPETITIONS: Or people like the Mayor, for example, to drive it.

RFJ: In this country the architectural competition isn’t used quite as much across the continent. They are used – and we’ve participated in competitions in Western Australia, Adelaide, Brisbane, but it’s less frequent.

COMPETITIONS: So I better understand the dates……you weren’t part of this firm for the Parliament competition?

RFJ: No I wasn’t. When I came back from school, MGT had just opened an office in Sydney and Thorpe headed up that studio. He was the Aussie that was involved in the Parliament house and that’s when I joined the firm.

COMPETITIONS: Where else did you go? Your bio shows you in Paris, New York, Los Angeles…..did you work in all of these places?

RFJ: I mainly worked – and spent my time in New York. I did get to meet Harry Wolfe in New York, and he had that interlude with Ellerbe Beckett and moved to LA and participated in the Kanzai Airport competition. There were only like four or six in that one; so I went to LA to work on that competition, and it was a great experience. He’s a very disciplined architect and produced some fantastic buildings – I thought his proposal for Kanzai was incredible – I really liked his scheme. One of the things I liked about it was it tried to create a space that could be shared by the airplanes and the passengers. You know, to board a plane you normally go through the tube and don’t really see the plane. Whenever you don’t do that – when you go across the tarmac up into the plane – it’s a much richer experience. So his concept was this roof that would cover the lounges and public areas and the nose of the plane would sort of move in under the roof (into a shared space).

COMPETITIONS: What about Paris?

RFJ: Oh yes, I had a good friend in Paris, who studied with me. He was in Paris when I was in New York, and my wife at the time was very interested in Paris, so we hopped over the Atlantic quite a lot. We thought we might move over there so I tried to explore working there for a while. I did work with the architect Edith Girard. Like many of the architects during that time, most of her work came out of social housing….Andre Serrano and Jean Nouvel was just starting around that time. So I worked with her and her husband on a competition. Competitions are integrated into the European design culture, and we worked on a housing project in the mountains. We finished that and looked at staying more permanently – and I actually had spoken to Kenneth about working in his Paris studio – but my wife had been offered a very good job here in Sydney, so we came back. You know one of the things about traveling like that – after you’ve been away for a while, it’s often hard to come back.

COMPETITIONS: I’ve noticed Australians stay out for long stretches.

RFJ: Sure, but it was good to come back. It was difficult and tough at first, but the culture of architecture has changed a lot in this city and this country.

COMPETITIONS: Being back, do you feel a sort of responsibility or obligation to advance a level of architectural understanding, or educate the general public – especially since you’ve traveled and had an opportunity to work in other places? Maybe obligation isn’t the right word.

RFJ: No, not the right word – I know what you’re saying but it’s not a sense of obligation. When you’re young in a place like New York it can be hard to get work, but there is a very vibrant culture in a city like that, so it’s good to be a spectator, too. It’s pretty satisfying. If you move to a city that isn’t quite like that – not quite as vibrant – then there is more work to be done and you might need to contribute more to build and strengthen that culture. So you have to be more active and I think that’s a natural thing – it can come as a result of travel and work interest — but it doesn’t need to. I’ve been very interested in the public domain. It’s been a central area of concern for me, so I’m very interested in contributing to the making of cities and the making of urban areas. The thing about Australia is that it’s a very urbanized country. The image of the bush is what everyone sees, but it’s incredibly urbanized………..very dense with a lot of people living in cities. I’m really pleased I came back. I love this place and I love working here. The way the culture of architecture has evolved is great. We’ve gone from a situation where there had been a few central figures to a much more diverse field. There’s a lot more stuff happening and the client base is a lot more educated and a lot more visionary, which you need.

COMPETITIONS: I pulled a quote off your website that I thought was very good, and that is “we believe the project of architecture is in the end to reconcile our presence in the world.” Specifically, though, I’m wondering if you have examples of your work – competitively garnered or not – that you would point to as getting closer to that ideal?

RFJ: Yes. But I suppose we tend to always be a little more enamored with the building we’re doing now (laughing), but the law school is a very important building for us. We’re also just finishing a little building in Surrey Hills – it’s very small – a little hybrid public building. It’s a library, a community center, a childcare facility – all in one little three-story building. It’s on Crowne Street in Surrey Hills. These would be examples of what I’m saying there – and at the UNSW we’ve done quite a few buildings that would demonstrate that, too. The Scientia is right at the end of the main axis and it was intended to represent and embody something of the spirit and inspirational quality of the university.

COMPETITIONS: Specific to competitions, what are the ones that stand out as really supreme – from either a competitors or jurors perspective? One that really shows what the competition can deliver?

RFJ: The easy answer for that – of course – is the Opera House. Totally successful with an amazing result – so that’s an easy one to point to. But it also demonstrates some of the challenges in that here’s the young architect from Denmark who steps into this political situation and it becomes a very, very difficult thing to manage – as anyone who’s worked in the public domain would know. It’s one thing to win a competition, but to build the building requires an enormous amount of skill and experience and ability to work with many people. It’s an easy example to point to, but there aren’t many like it.

COMPETITIONS: That’s a good one, but are there any others you have a more personal, critical perspective on?

RFJ: Sure, the Scientia at UNSW and the law school – but those are easy for me because I’ve been close to the process. But the one that’s very interesting, actually, is the MCA competition. We didn’t win the actual competition, but we got a lot of very good feedback as a result of it – and we subsequently won an award from the European World Congress of Architecture for an un-built project. It won the un-built prize, but ironically it tied with Foster’s “Gherkin” building – which was un-built then, too. So even though we didn’t win the local competition, the scheme was well received locally and internationally. This is an incredible site with the bridge and opera house, etc – and the short list is also incredible: Rafael Moneo and Steven Holl – as well as a few other internationals.

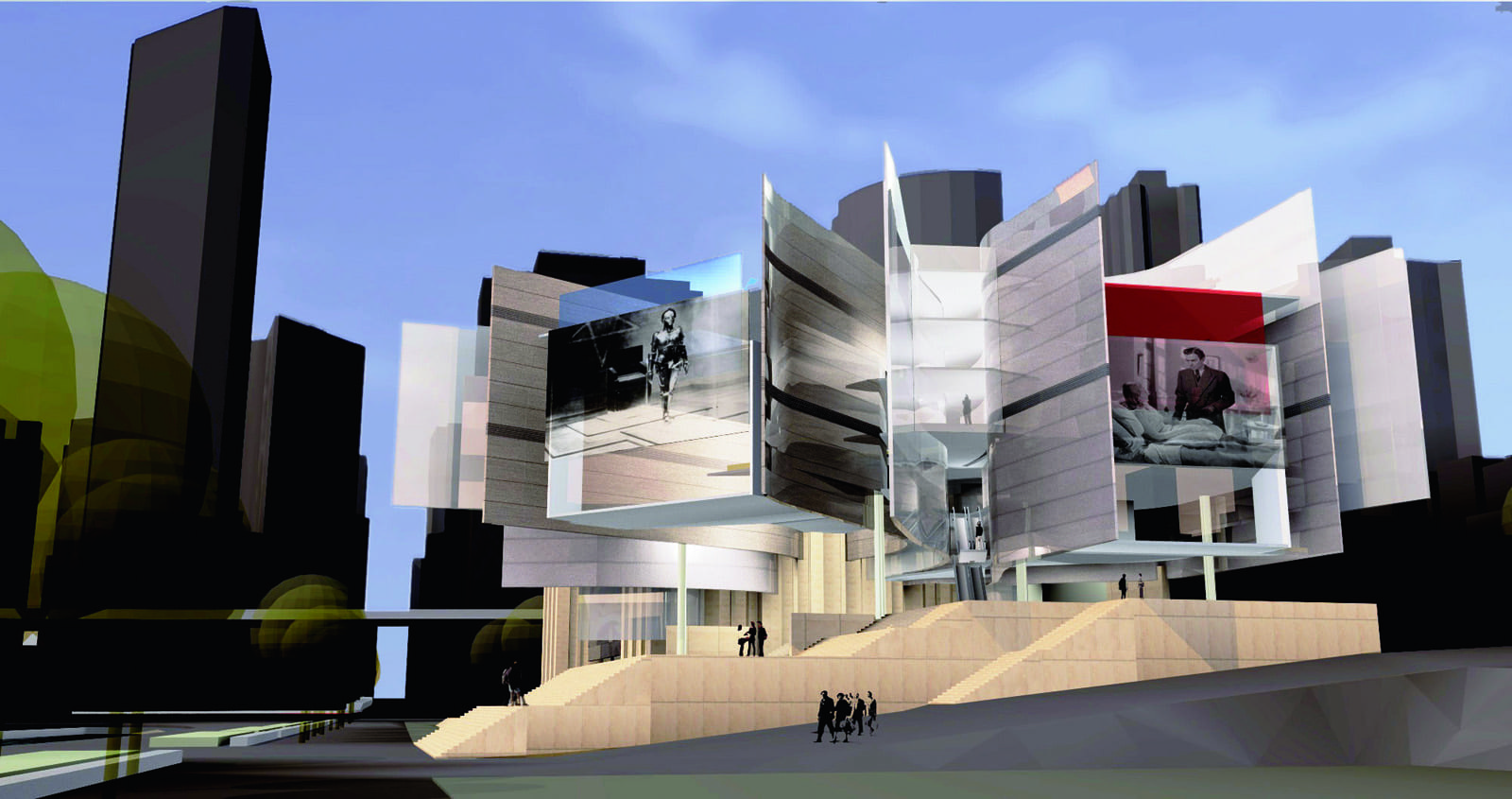

Museum of Contemporary Art + Sydney Moving Image Centre (competition 2001)

COMPETITIONS: A lot of big names?

RFJ: Oh yes. Ironically enough, when I was in Europe I actually traveled around Spain looking at Moneo’s buildings – because I really like his work – and it was a great privilege to be on that list. The project had a great site – and we certainly had enough time – so we went back and experimented a bit. We were building models for almost a month – but because of the power of the site, we looked less at the requirements in brief at the beginning and played more with form. We really looked at how you can extend this building and relate to the harbor and make the place…….so it was very experimental and it led to a series of formal explorations that were all born out of the MCA competition. Of course it was a great experience and it led to a development in our work – our work took a turn at that point and it’s proven very fruitful. We did a lot of research on the site and looked at the qualities of the site and the evolution of the urban form, here, and it really became a project that attempted that reconciliation while it generated something quite new. What’s interesting about that point – and I suspect most architects would agree with this – that is what gives the greatest value to the competition itself, irrespective of the result. If you engage competitions with that particular spirit and you view it as an opportunity to develop and explore your work – even if you don’t win, it doesn’t really matter. I mean, of course it does matter, but I think if you’ve taken it on in that way and had an opportunity to grow, you’ve won something even if you didn’t “win”.

COMPETITIONS: I didn’t get a chance to see any of the details in the images, but your blades concept – from the reviews that I read – it sounds like the blades was the high point and the thing you took the most flak about.

RFJ: Which is what you’d expect.

COMPETITIONS: And then there’s the relationship between this site and the actual opera house, which a dramatic building and something that’s effectively evolved into a type of brand for the entire country….I mean that’s pretty incredible and to have this kind of proximity, the tension must have been huge.

RFJ: That’s right. You can’t ignore it.

COMPETITIONS: Taking on that formal exercise like you’ve described sounds like the first thing someone like you would want to do.

RFJ: I thought so. The good thing was, we had a bit of time to extend that process – to do more exploration.

COMPETITIONS: How long did you have – 6 or 8 weeks?

RFJ: I can’t remember exactly how long – but it was quite a bit more than that, I think, because we had to accommodate the internationals. It was nice, though, because we all got to present on the same day. We all went out and had a lunch together. That’s one of the nice things about working as an architect, I think, that sense of camaraderie with your peers. You’re competing, but there’s almost always this terrific respect.

COMPETITIONS: Would you take some of these things back to the academic world with you – for example, would you push for this model – maybe not universal transparency, but the more open presentations?

RFJ: Yes, I think I would. I wasn’t sure what to make of it at first, but having experienced it I thought it was fantastic. I think competitions are a bit like building contracts. They have a basic value to them, but a little bit of it is determined by the course taken. The type of competition needs to suit the project, so I think for major projects like that – where it will say something major to the community – we should make it as public as possible. Maybe in other instances, though, its’ not the right way to go and in other instances I can see it being inappropriate for projects. It doesn’t work for everything. In principle, though, it’s a very good way to procure a design and a team.

COMPETITIONS: Over the years, then, how has the competition enabled your ability to collaborate with other professionals? Your portfolio has an unbelievable diversity of work – would you say the competitive environment has given you more of an opportunity to build those relationships?

RFJ: Absolutely. Our practice wouldn’t have become anything like this without the architectural competition. Of course, we’ve lost a lot of competitions, but we’ve been included in groups when we might otherwise not have been. We might’ve offered something a little bit different – or even had very different experiences – but they were interested in us and if you’re looking at a group of five people, they think “we might just pull those guys in.” Whereas, if we had gone through a more orthodox process like an interview or credentialing or something, we might have fallen off the list. But somehow we’ve managed to get on the lists – and maybe you win – and then we open up a whole new area of work. In that way the competition is a leveling feature where design becomes the real focus – and therefore creates the opportunity for practices to grow. I think that’s one of the main reasons people do competitions. You can get a break out of it, and even if you don’t win, you might be able to get on another team later. Of course with the Europeans – that’s the way it is. Australia is developing in that way and it’s catching on – and in some ways we’re very progressive in the ways in which competitions have been used. I’m an absolute supporter of the process. It’s a process that’s got an enormous integrity – assuming it’s managed well and done well. I suppose it is like contracts, too. The method isn’t always foolproof. For example I’ve been in competitions where it’s gotten crazy – like designs for major buildings getting down to excruciating details. It gets down to two people – and it’s already been through several months – and the jury wants us to get down to buffering in wall thicknesses for lifts (elevators). Ridiculous. Fine points of technicality that you get into because it might be a situation where there are 25 technical advisors and they all want something different. Then you run the risk of losing the essence of the competition and it can lead to teams being asked to do an inordinate amount of work. We actually got to the point where we had to tell the jury to stop in one case.

COMPETITIONS: Are you asked to sit on juries frequently?

RFJ: Yes, but I do more competitions than I sit on juries. Competitions are great, but it’s also terrific to sit on the other side of the table and see work presented and see what others are doing. It’s very impressive. The effort and commitment people put into these things is monstrous.

{/reg}