Cite de la Voile Eric Tabarly, Lorient, France, 2007 – Winning competition entry [2001] (Photo: Luc Boegly)

COMPETITIONS: What inspired you to start your career in architecture?

Jacques Ferrier: First and foremost, I was fascinated with the way buildings were built, with their structure. Before I was trained as an architect, I was trained as an engineer – in science and mathematics – and then I pursued architecture. When I began my architectural studies in architecture, I realized the specificity of it, as compared to art or engineering. In a way architecture is less complex because there might be less calculation involved, but more complex because you work directly with people, with site contexts, etcetera.

COMPETITIONS: And what inspired you to start your own firm?

JF: I started a firm with a friend of mine who went to school with me. We started in 1990, as sort of a first run. I opened my own office in 1993, sixteen years ago now. We were lucky because it was the end of the golden age of public competitions in France and it was possible, even if you were a young architect, to be invited to participate in these competitions. When I started my practice, I managed to get invited to one such competition for a university laboratory building. With this building, I received a national prize, which was typically awarded for an architect’s first work. A few weeks after that, I won another competition for an industrial facility for the city of Paris – a water treatment plant. It was interesting because the brief for the building was very typical, but the lasting impact was on the site as a whole.

COMPETITIONS: Who were your mentors when you were receiving your education and who were your major influences along the way?

JF: Charles Eames. I always loved his work because he was involved in architecture, design, toy designs, even card deck designs. And now for the French Pavilion – the project we are working on for the Shanghai Expo – I have this opportunity to design the building itself, but also the cinematography, some objects inside the building, other content within, even the packaging of the perfume for the pavilion. I will also assume the role of a movie director, working on a film that will be shown inside the French Pavilion. Our office is working with a film crew and we will begin filming very soon.

COMPETITIONS: Is this your first movie?

JF: Yes, it is. And it may be my last one, who knows! But, you know, Charles Eames was doing some short movie directing as well. So similarly to Charles Eames, I don’t think I like the limit of architecture and for the last sixteen years my practice has been concentrating on more than just architecture. Because the practice is gaining a certain image, it has been advantageous to us not only in acquiring more projects but also, and what I am interested in more, is that we are acquiring many different types of projects. In addition, I am working on a movie, I am working on a chair and a table for a French manufacturer, many different things, more than just one project type.

Cite de la Voile Eric Tabarly, Lorient, France, 2007 – Winning competition entry [2001] (Photos: Luc Boegly)

COMPETITIONS: You have entered a number of competitions throughout your career. Was there any one competition that you feel was a defining moment for your career?

JF: Not just one. The first one, as I said, was the one for the university laboratory because it allowed me to launch my own practice and the recognition we received when we won became the foundation for the other projects to come. Then, there was also a project for the tramway workshop and garage in Bordeaux that allowed us to experiment with aesthetics, go in a certain direction. In this project, we concentrated on developing a very efficient structure – one beam only, as we positioned beams at intersections of two curves and the bracing was done by the columns. It was, in a way, a continuity of the first project we worked on, in terms on exploring issues of efficiency. But it was more natural and developed, as we were starting to play with the form and shape, whereas in the first project we kept it very simple. In this respect, this tramway project was a change – the simplicity was there but we introduced the use of more original material. In the translucency of glass, for example, because of the shape of the building there is animation that was maybe not exactly on the same level of development in the previous project.

Another competition – the project for Airbus, in some ways, is related to the tramway workshop in Bordeaux. I mean, we did not have very many built projects yet at that time but after Bordeaux we received two different projects that were more extroverted, obviously with a very strong straight-forward program. One was Cité de la Voile and the Airbus project – two projects that were sort of more high level competitions. So those were opportunities to show that I could win these types of competitions, while still sticking to the values of my practice. It is very important to me to not to be compelled to change your aesthetic or design principles. It is not such a matter of formal architecture, because it was a way to convince a client, like the chairman of Airbus, that the project would have a strong image, but that it would also address the needs of the company.

AIRBUS, Toulouse, France, 2006 – Winning competition entry [2005] (Photos: Luc Boegly)

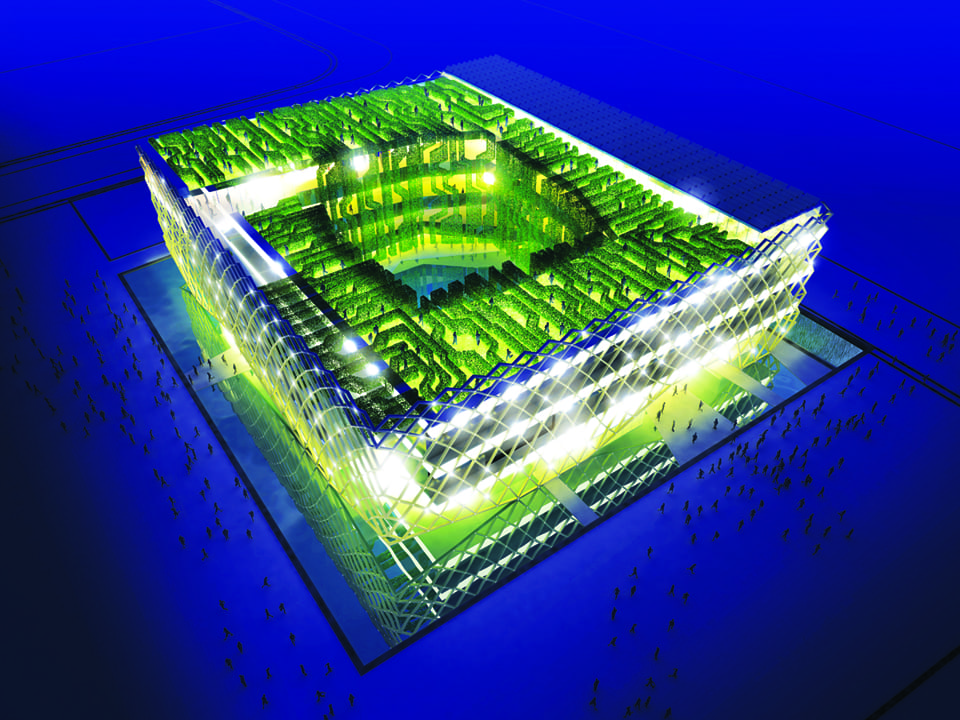

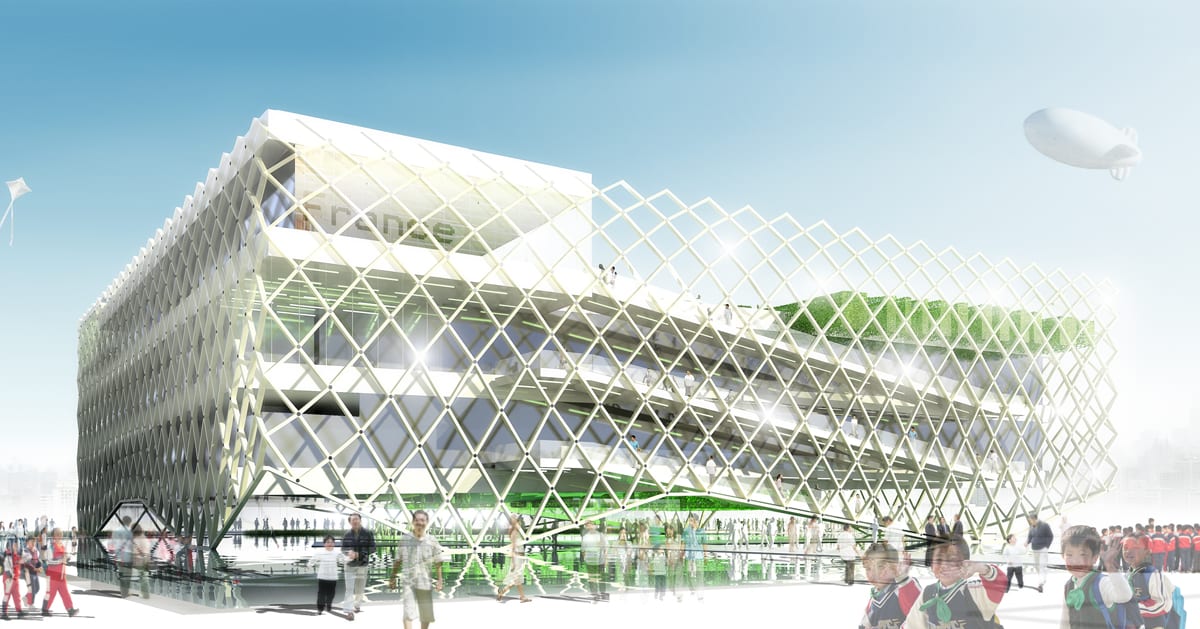

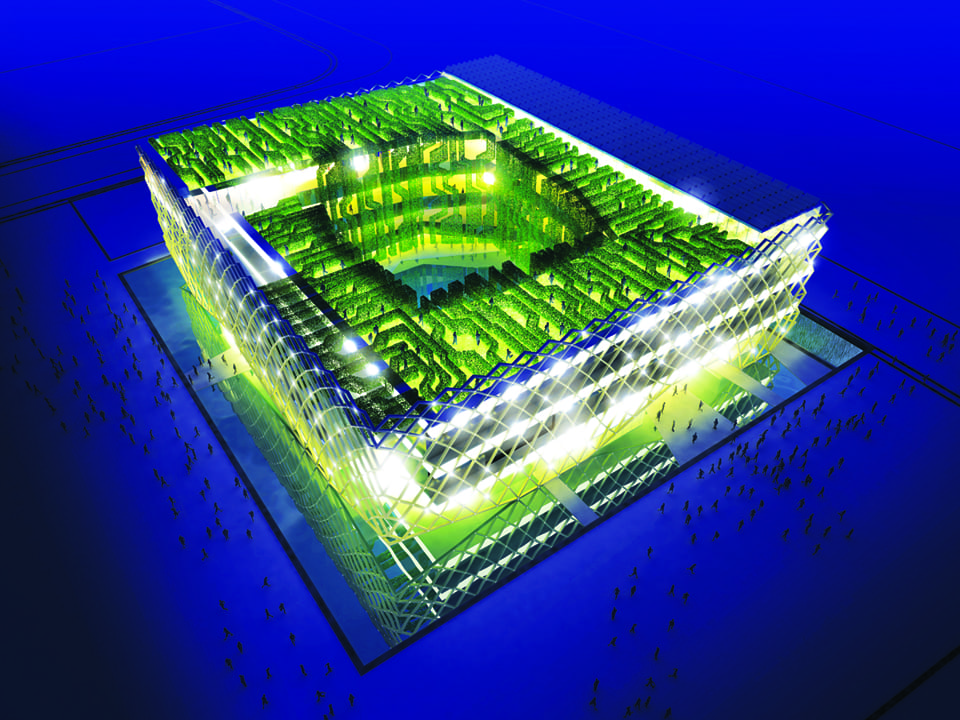

AIRBUS, Toulouse, France, 2006 – Winning competition entry [2005] (Photos: Luc Boegly)And the last one is the French Pavilion – for two reasons. First, it is a very prestigious honor to win such a high level public commission, to represent your own country at a World’s Fair, and second, because its place at the Shanghai World Expo will make an important statement as to our firm’s approach towards architecture. So the pavilion is not only representing France, but it also says how I see the future of architecture in the cities.

There is no clear differentiation between the building and its content. The building can be seen as the first element of the overall scenography. That is why the French Pavilion contains this vertical garden and this garden becomes a part of this scenography. By introducing our philosophy at the Shanghai Expo, this project gives us a strong identity and a number of new opportunities. Thanks to the exposure from the French Pavilion, we just recently completed a façade for a shop in Hong Kong, we have been asked to design an info center for the city of Xian in China. So some of the opportunities opened up that we didn’t have before.

All these four or five competitions really mark the evolution of our practice.

French Pavilion, Shanghai, China, 2009-2010 – Winning competition entry [2009)

French Pavilion, Shanghai, China, 2009-2010 – Winning competition entry [2009)COMPETITIONS: How have you seen the organization of competitions in France evolve or change over time? Have you seen any organizational changes?

JF: The big, big change and a bad change, in my opinion, is that during the early years when I started the practice we were allowed to present our entries to the jury. Generally, a minimum of three and an average of five to six teams were invited to participate in a competition and every team was allowed to put their names on their scheme. After the teams submitted their proposals, these schemes were allowed to be presented in front of a jury and by the end of that day you knew whether you won or lost. It was a more fair process to present a scheme in such a way and it was also a good way to end a competition process, during which you spent two or three months working hard on a project and, even if you lost, since you have presented your scheme you have received the feedback from the jury. You have seen whether they were interested or had any criticism.

Now, competitions are anonymous – it has been this way for at least six or seven years now. The process of presenting before a jury is no longer allowed by the law. Now, we still spend a lot of time on a project, we still send the presentation panels in, but then we have to wait for the results. And this is a big loss, everyone is always complaining about that – the clients and the architects.

COMPETITIONS: What competitions, besides the ones you had already mentioned, are you involved in now?

JF: There is the one we had just recently completed that Jean Nouvel won about two weeks ago. It was a very short competition – three weeks long. Now we are starting another competition for a university in Morocco. A couple more competitions that we are working on is the one for a swimming pool in the North of France and one for a Lycée Française (French School) in Beijing. We are always working on maybe two or three competitions at a time, probably twenty or thirty a year. So if you multiply that by sixteen years since our practice started, it is about three hundred or more competitions and we win about one out of every thirty. So if you can imagine, we use some of the competitions as opportunities to develop many of our ideas from previous competitions, so that not all of the design progression is lost.

COMPETITIONS: You are branching out into international competitions. Do you see any significant differences between entering an international competition versus a French competition?

JF: Oh yes, definitely. In France we are very comfortable doing competitions, because of the pay, because we get about two months. When we do a competition in Kuwait, or China generally it is a bit more stressful, because you are generally not paid – it is a system of prizes; and it is also the wait. In France, we have been a little spoiled in some ways, because the competition process is more comfortable.

COMPETITIONS: Do you find it possible to immerse yourself in the culture of another country when you enter an international competition?

JF: I try to. I mean, I have been traveling to China for five years now, because my first opportunity to do a project there was when I was invited to enter a French embassy competition in Beijing. And shortly after that, we were commissioned by the city of Shanghai to do a school. For the French embassy competition, a three day trip for all the competitors was organized. I ended up staying there for eight days to visit Beijing, to try to learn a little bit about the architecture in China. I read a lot of books, novels, books of history of architecture in Shanghai.

For the French Pavilion, I take trips out to Shanghai at least once every month. I just spent two days in Shanghai and then back in Paris. Most of the days spent there are packed with meetings but at least my trips there have helped me get a better understanding for the city of Shanghai. During my visits I took a lot of pictures of the scenery in Shanghai, Beijing and Hong Kong and I will be showing those pictures in the French Pavilion as well. It was not originally planned like that but with the fact that I had taken so many pictures in the process of trying to understand the city, I am now able to show the imagery of French cities and also an often contrasting vision of the French architect in the Asian cities.

Even when I am participating in competitions in France, I try to spend some time in various French cities to get a sense of understanding for the local people and the local surroundings.

French Pavilion, Shanghai, China, 2009-2010 – Winning competition entry [2009)

COMPETITIONS: In your book, Useful: The Poetry of Useful Things, you mention that the beauty about many industrial buildings is that they are often derived from the direct simplicity of their requirements. Has your interest in these utilitarian buildings carried over into your other projects, where the demands may be more complicated?

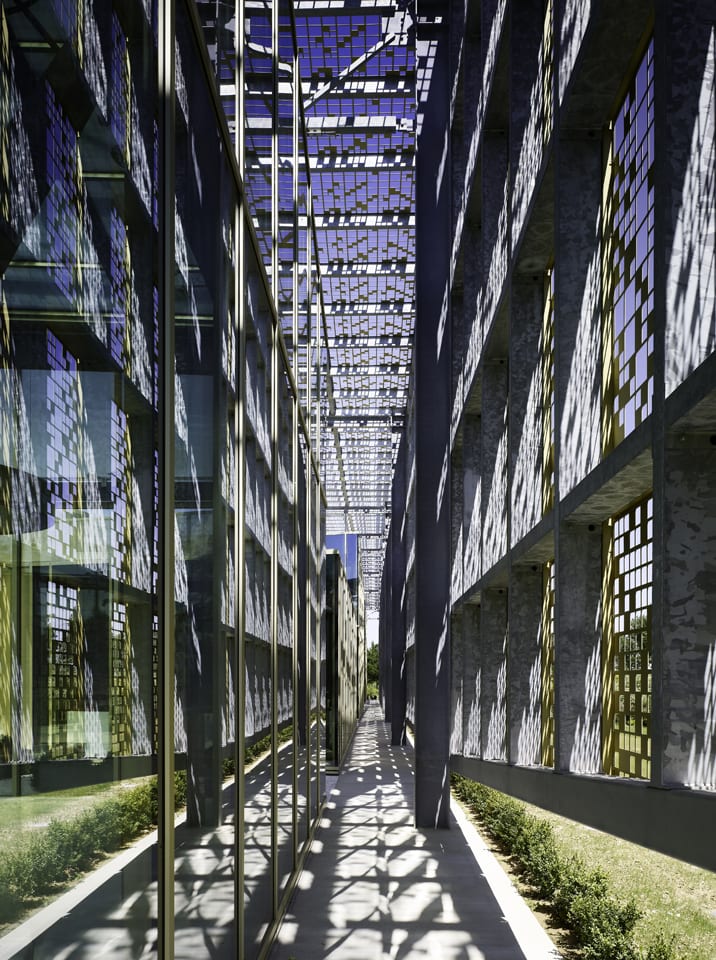

JF: Now when I am dealing with more sophisticated demands for buildings, I look for inspiration in the simplicity of the industrial buildings and create additional visual interest through the use of materials. In the headquarters of the Piper & Charles Heidsieck champagnes in Reims, for example, the simplicity is seen in a utilization of a very basic curtain wall that, at the same time, allows for creation of the space between the two skins where the light and shadow play creates something that you don’t find in most industrial buildings. We played with the views from within the building, the reflections, the points where the outside and the inside begins blurring together and is facilitated by the interplay of glass and the perforated panels.

With this project we wanted to produce a building with a strong image that makes an initial impact on its visitors. In fact, when they get closer they will realize that is all made possible by combining very basic things together – once you are inside the building and seeing the double skin – the steel structure reveals the simplicity of it all.

COMPETITIONS: In most typical high-rises, most of the space is occupied by offices. Are there limitations to flexibility of space use or does your idea for concept offices and their flexibility still work within high-rise structures?

JF: Hypergreen Tower is based on our ideas of such flexibility. And the original idea behind a concept office emerged when we decided to work on it, not as part of a competition but in an environment similar to that of a science laboratory. We wholly concentrated on the research aspect of the project and the monetary sponsorship came from the Lafarge Group for whom we developed the concept. We came up with an idea for a very transparent, light-filled building – actually, it was really a glass box. With a double skin and an integration of photovoltaic panels, it could be very efficient in terms of energy consumption. Our calculations estimated that this conceptual building would be using 50 kW an hour per square meter, which turned out to be a very low ratio.

At the same time, while working on the concept, we wanted to stress that it was not only the matter of energy efficiency. We wanted to address two other very important topics and the first one was how do you work inside a building? We compared office space to being able to work like a hotel – you can work where you sleep, or where you eat or where you read. The second topic was about the relationship between a building and a city, and the integration of those two with one another. After that research the concept of the Hypergreen Tower came about. It is envisioned to be a mixed-use building. An investor asked us to design it for La Defense mixing housing, hotel, office and commercial space. It is not the tallest of the towers, only about 200 meters, but it is very efficient and it aggressively tackles the three topics of research – the way it connects to the city, its mixed use and its efficiency.

COMPETITIONS: Recently, President Nicolas Sarkozy invited architects to reimagine Paris as less grand, but more integrated with its suburbs, emphasizing his more practical goals for the city. Do you see this emphasis on improving the infrastructure as a logical step in reducing the overcrowding of the city?

JF: The center of Paris is very small if you compare it to the overall size of the city. In the administrative zip code, there is about a 2 million population as compared to the 12-14 million of what constitutes Ile de France. I think the real issue here is a political issue of defining ways to say how to interconnect a larger area called Paris with its center, instead of having so many small communities all around. The second issue is how to address the existing infrastructure of Paris – the existing transportation, the metro. Only after we deal with these problems can we begin looking at architecture.

Intern Matt Piker: You can see the attempts to address the problem as most of the projects shown at the Cité de l’Architecture are geared towards transportation.

Yes, because transportation is such an important issue and it is easier to address, because the political aspect of it is difficult to change.

Piper and Charles Heidsieck Champagnes Headquarters, Reims, France, 2008 (Photo: Luc Boegly)

Piper and Charles Heidsieck Champagnes Headquarters, Reims, France, 2008 (Photo: Luc Boegly)COMPETITIONS: Do you see more architectural competitions focusing on the improvement of the transportation system coming out, as a result of this move?

JF: Yes, now that there is so much interest generated about the subject. The importance of Sarkozy launching this new idea about Paris – the exhibition at the Cité de l’Architecture was very successful in terms of people attending it and talking about transportation improvements as well as architecture. The question is now how are we going to be able to make it into reality.

COMPETITIONS: A lot of your projects, like Hypergreen, are heavily research-oriented. Do you find that entering competitions allows you more opportunities to expand on your research?

JF: Yes, definitely. This is how I see the competitions business. The good thing about receiving a direct commission is that you can create a link with a client the very first day. The bad thing could be that, since the project may not be well-defined, it might be difficult to change a client’s mind about something or to move a project forward. Often, if it is an office building, the client might just expect you to design the same office building they are accustomed to for years. When you are working on a competition and propose a new scheme, if you are chosen, that means that you have already received the legitimacy of having won with this scheme. Competitions always allow for an opportunity to propose something new. I mean, a good competition should always allow you to explore new ways and new solutions.

Sometimes, however, without having a direct link with a client, you almost expect to lose a competition, if you cannot explain a design idea or if an idea is so strong in its presence that it is going to frighten the client. On one hand, you are compelled to be somewhat restrained, but you are also allowed to explore and research the ideas of your interest.

Piper and Charles Heidsieck Champagnes Headquarters, Reims, France, 2008 (Photos: Luc Boegly)

COMPETITIONS: Are most of the competitions that you enter open or invited?

JF: Until about two years ago, we have been largely concentrating on invited competitions. Now we are getting involved in open, international competitions, just to get some fresh air and expand. And it is a good opportunity to explore new territories and contexts. I hope that in the United States there will also be opportunities for new firms like mine to get involved in various projects.

COMPETITIONS: In another one of your books “Jacques Ferrier, Architecte”, you state that “the starting point for any architectural project should be loving the world as it is”. What do you see wrong about changing the world and improving upon previous architectural mistakes?

JF: In the twentieth century architecture, the focus was more on how to create a masterpiece, how to control a building’s context instead of letting a context inform a building. Now it is more important to go back to the context and to try to find not only innovative, but also context and site-appropriate, solutions. This is not to say that we need to do only ordinary architecture or that we can no longer make strong statements with architecture, but it is to say that we cannot always strive to recreate a Bilbao Guggenheim.

In the twentieth century, we saw some of Le Corbusier’s masterpieces that did not work at all on the inside; the Farnsworth house that is beautiful to look at but that requires so much energy to cool in the summer and to warm in the winter. It is in this respect that it makes sense to love the world and the site conditions as they are and adapt to them. It is why it is important for me to go back to the simplicity of the industrial buildings or the rural barns, to study how they age, blend with their landscape. This is where it becomes possible to say, “Wow, this is an extraordinary building”, while at the same time relate and identify with a building as it is part of your own life. If you overdesign something, you cannot relate to it as well. With the use of ordinary materials, in a way, a structure finds its relationship to other buildings and to you.

COMPETITIONS: So a building can still be iconic, without being an object.

JF: Yes, exactly. Even if your client is expecting a building from you capable of changing the street or the surrounding area, or the city, it is possible to achieve that change and still allow the building to not feel out of place, to be a part of its surroundings.

Tour Signal, Paris, France – Competition entry [2008]