Nara Convention Center Jurors James Stirling with Jorge Glusberg (right)

GLUSBERG: What do you feel are the basic components necessary for good design?

STIRLING: I think every building must have at least two good ideas. I don’t see the design process as a sudden blinding flash of insight. That might be true for a structure that has one main purpose, like a stadium or an office building; but, in my opinion, it won’t work with a multi-functional building. That, in fact, is what most of the projects in our office tend to be.

GLUSBERG: Then how would you describe your process?

STIRLING: We really try to be careful and conscientious in our analysis. We work in a very linear fashion so that the final design reflects the path of decision-making.

GLUSBERG: You just said that few of your buildings have a simple program: but what about the Science Center in Berlin?

Berlin Science Center Wissenschafts Zentrum (photos: Stanley Collyer)

STIRLING: Yes, you’re right. That is an office complex, but it also incorporates an existing Beaux Arts building that was remodeled into several lecture halls. In the office building we had to provide three hundred similar offices for researchers. We were looking for an architectural solution, rather than for a solution to the program which would have been very repetitive. So we created a group of five adjoining buildings surrounding a courtyard. The space between the administration, the sociology and the environment departments, the library, and the archive helped us to overcome the monotony of the program.

GLUSBERG: Looking at your recent museum projects—what in your opinion are the similarities between the Clore Gallery and the Neue Gallery (Neue Staatsgallerie Stuttgart)?

View to entrance of Staatsgalerie and existing museum in background, Stuttgart Photo: ©Stanley Collyer

STIRLING: The Clore Gallery was an extension of the Tate to house the Turner Collection. The halls are all at the same height as the old galleries, so that the public can pass from the old to the new building without any change or level. We applied the same principle in Stuttgart where a key objective was to achieve a smooth transition between galleries.

GLUSBERG: The space is far more constrained in the Clore lobby.

STIRLING: We wanted to create a promenade through the entrance lobby as a prelude to the exhibition galleries—maximizing the space, so to speak.

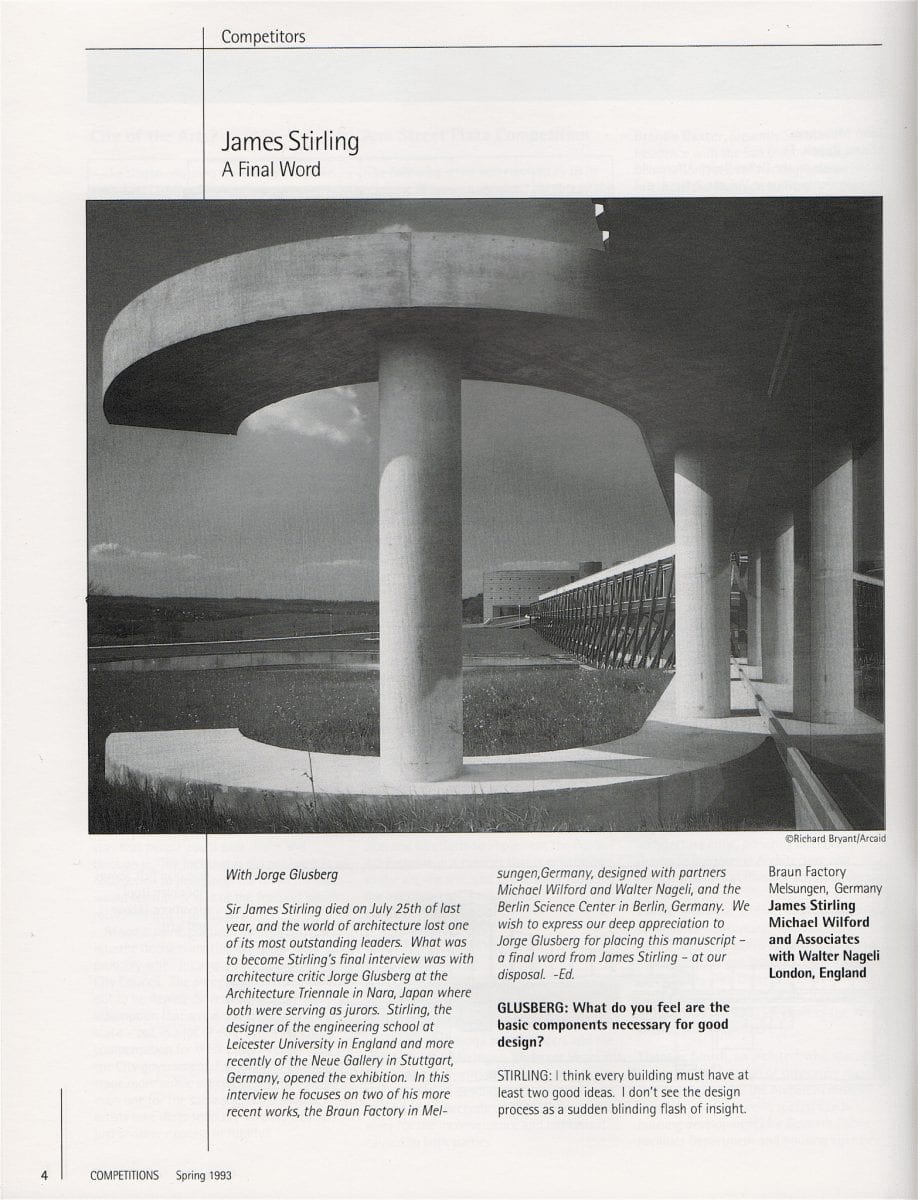

GLUSBERG: What influences lie behind your design for the Braun factory in Melsungen?

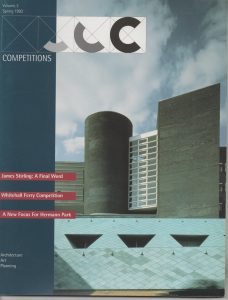

Braun factory, Melsingen, Germany (COMPETITIONS, Vol 3, #1) All photos: ©Richard Bryant

STIRLING: I like to think that we don’t follow any particular influence, and I like even less the thought that we might be influenced by the design of some historical buildings.

Melsungen is a medieval village; so there is a lot of history in it. Of course, nothing is created in a vacuum; so it we are trying to find precedents, I would say that we are coming from the functional tradition that places us close to the beginning of the modern movement and its rejection of historicism.

GLUSBERG: This project seems to be very dear to you. How would you describe it?

STIRLING: In 1986 Braun organized an invited international competition among eleven different offices. Actually our proposal didn’t win, but the client decided to build our design anyway.

GLUSBERG: Ludwig Braun said it was time to put an end to minimalism in the design of post-war industrial buildings. Without any doubt, he was looking for new forms and new images.

STIRLING: We thought our design should recognize the cultural elements of the landscape like the viaducts, bridges and canals. We also wanted to include natural elements of the landscape—such things as woods and tree alignment. This was a challenge because we weren’t working in a historic city like Berlin or Stuttgart, but on the outskirts of a small village on a forty-five hectare site. It was a small paradise running down the side of a hill filled with greenery.

GLUSBERG: What were the main functional areas in this complex?

STIRLING: There were three areas: administration, production and research, storage and distribution. We located the administration building at the top of the hill, and this is the first thing you see when you come from Melsungen. Each of the functions is represented by different volumes. I should stress that the program asked for a 1,300-space car park, which would have involved a major extension of the site. However, theform of the valley suggested a two-level approach, and we decided to build a seven-story parking garage approached by a pedestrian bridge half way up. All seven floors are connected to this bridge by stairs hidden in a double wall 250 meters long. This wall serves the purpose of dividing the site into front and rear areas. The front section is designed as an English garden—an open area with a watercourse resembling a cascade, a lake, and terraces, all surrounded by trees. The storage and distribution center is elliptical in shape and faces the back. It looks lie a scaled monster with several mouths. The long curvilinear wall allows several lorries to be loaded or unloaded at the same time.

GLUSBERG: Your works extend over three decades. How would you define your working philosophy today based on this previous experience?

STIRLING: As I have said before, functionalism has been the mainstay of my architectural beliefs and practice. I think these ideas can be part of a broader spectrum that can embrace other designs and other designers; but I believe that the theory of functionalism has been the biggest contributor to the progress of architecture in our century.