COMPETITIONS: As has been case with many architects, your career got a very big boost by virtue of winning a competition — Colton Palms Senior Apartments. Was that the very first competition you participated in?

VALERIO: No. It wasn’t the first, and it wasn’t the last. It was interesting in that we won, and also won a PA Design Award for it and an AIA Honor Award for the project when it was finished. It covered the gamut of awards that one could win with a project. And it got built almost exactly the way it was designed for the competition.

COMPETITIONS: Was the competition open or invited?

VALERIO: It was open, and there were about 140 entries from around the world. There were five finalists in the 2-stage competition, and we were selected at the end of the second stage.

COMPETITIONS: Do you recall who ran that competition?

VALERIO: Michael Pittas, who did a very commendable job. The two key jurors were Rob Quigley and Don Lyndon. In hindsight, it was one of those things where all the stars were alligned and there was a very dynamic city manager (Frank Benest). This was his first job as city manager. He went on to become city manager in Brea, California, a wealthier suburb. Now he is city manager of Palo Alto. He recently said to me that one thing he was always trying to get communities to do was to invest in their downtowns. ‘Here in Palo Alto, nobody wants any more investment in downtown.’ Frank was very innovative, in that he used the competition process to get something to happen that probably could not have happened any other way. California in the early 90s had a law which said that, ‘if you set up a redevelopment district, you could capture the increase in real estate tax revenue in that district and use it to help finance the development.

So it was a kind of bootstrap sort of approach called tiff financing, which is very popular all over the U.S., including in Chicago. You have to set aside 20% from that funding mechanism for

affordable housing. So everybody set up these greenbelt districts and this set-aside fund. But nobody wanted affordable housing, because affordable housing equated with subsidized housing. It didn’t matter that the people that really wanted to use the affordable housing were seniors from the community who didn’t want to leave, or policemen or firemen who couldn’t afford to live in communities they were serving. People were just against affordable housing.

Colton Palms Apartments (Competition winner 1988) Colton Palms, California

Photo: courtesy Valerio Dewalt Train

Colton Palms Apartments (Competition winner 1988) Colton Palms, California

So Frank came up with the idea, if he could create enough buzz about the project and really make it into this event, he could get the city to build affordable housing projects. It turned out that they had an abandoned grocery store in their old downtown area, which covered most of a city block. The city had taken control of the property. So he had the money and the set-aside. He had this piece of property which had to be redeveloped; but he couldn’t get the city to just do it. So he came up with this idea of doing a competition, hired Michael Pittas to organize it, and it worked. There was all this publicity and notoriety; this competition was like a city festival. It was a very public event where people showed up for the presentations. So not only was it an architectural event; but it had a real social underpinning that was really admirable. Without that mechanism, I doubt if Frank would have been successful.

COMPETITIONS: In retrospect, would you have any clues as to why you won?

VALERIO: I know all sorts of reasons why we should have lost. We don’t go into competitions with the idea that we are plotting to win them. We go into a competition because we think that the program is interesting. It gives us an opportunity to separate ourselves from the client for a moment and look at an architectural problem purely as an architectural problem. When you are hired in a traditional way by a client to do a building, it’s really a process that in many ways really doesn’t reinforce good architecture in the sense that you go through an interview process — at most there are two interviews, and at most the client has seen you for 3-4 hours — and they are deciding to hire you to do something that at the minimum will take two years and might take 4-5 years to complete. There is this thing called cognitive dissonance, which happens whenever somebody makes a decision and then decides they have made the wrong decision.

When you get hired the conventional way, and if you are a smart architect, the first thing you recognize is that you need to keep selling to the client, to keep convincing the client that they made the right decision.

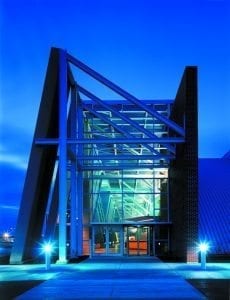

3Com office and production facility, Rolling Meadows, Illinois

When you get hired the conventional way, and if you are a smart architect, the first thing you recognize is that you need to keep selling to the client, to keep convincing the client that they made the right decision. So you sit down with them and try to figure out what they want, and then do good architecture and, at the same time, give them what they want. I think this is a conflicted process. What is beautiful about the competition process is that the client, because they are very concerned to make sure that the competition entrants don’t run off in all sorts of goofy directions, they actually sit down with their adviser and carefully weigh out what they want. They are far more conscious of expressing themselves in a competition process than they would be in a normal selection process. First you get a brief from a client which clearly defines — or should define — what they really want. Then you get to develop your idea without all this noise of forming this relationship. It’s really kind of a liberating process. The result is, when we submitted (our boards) to that competition, they were pretty far out, even for today in terms of the way we presented that project. I later learned from jurors that initially four finalists were selected. Since they wanted five, they said, ‘well this is a pretty radical solution, but let’s put it in the mix anyway. We were told when we went to the first session that we were one of the five finalists; but we were clearly fifth among five.

Undaunted by that, we didn’t sort of pull back in the second stage. We said, ‘If we’re here and are fifth, we might as well just go for broke. So we took our original concepts and tried to prove that those ideas really worked. For example, one of our ideas was, in an elderly housing project the traditional approach was to put all of the public rooms together — the community room, administrative offices, library, laundry, etc. All these things are in one spot. One of our concepts was: this is California where it is great to be outside virtually every day of the year. So we spread all of these common areas out around the project. Each one became their own feature building. It actually became a town within a town. There were places to go, things to do, get out of your apartment and go to the library, laundry, etc. None of the other finalists did this. They all took the traditional approach by clustering these rooms together.

Evidently, during the final deliberations we gradually went from fifth to fourth to third and finally at the end of the day we were first. Again, I look at every competition where we really don’t expect to win. We won in this case and it was a great experience.

COMPETITIONS: How did Colton Palms lead to other commissions?

VALERIO: That is one of the more unpredictable outcomes of these events. When we won the competition, we thought we would be noted for doing affordable housing, and we will get more commissions there. And whenever an affordable housing opportunity does come up, we try to do it. Those commissions have been relatively few and far between, because most affordable housing is really done by people who don’t really appreciate architecture. You can look around the country, and there are a series of landmark affordable housing projects which have just been done wonderfully. But that’s pretty rare.

We won a PA design award for our project. When the project was complete in 1993, PA published a relatively long article on the design with photographs. Two weeks after the magazine came out, I got a local phone call from USRobotics, and they were looking to going to interview architects. When I asked him whom they were interviewing, there was RWP&P — the largest architectural firm in Chicago — Perkins and Will, etc. We only had seven people in the office; so we took all seven people to the interview. We had to make it look like we were a big firm. We got hired, and the company, US Robotics, had only about 200 employees at the time.

We did a small project for them, then another and another. When we were hired, they were about a $30M company. By the time they were bought out, they were a $2B company. We did every project for them for five years before they were bought out by a Silicon Valley company, 3Com. So we started to do work for 3Com, then other Silicon Valley companies. Right now, one of our main projects is a huge campus for eBay in San Jose. So instead if doing work for affordable housing developers, I end up doing work for very progressive companies, firms which are usually very interested in architecture. There is a direct line from Colton Palms to all this work; it doesn’t follow building typology, it follows that idea that design can really solve problems — make things work better. In retrospect, we can trace several million dollars of commissions back to that original competition.

Gordon Parks Arts Hall, UC Labs School, Chicago, Illinois Photos: ©Barbara Karant

COMPETITIONS: When you go after a competition, what are the deciding issues you must address before making a decision to enter?

VALERIO: We look at the jury, for that often offers a clue; we try to look at what they are saying in terms of the promises they are making; we look at the program. It is the combination of those three things and ‘Is it an assignment we are really interested in? Is it a jury that is likely to appreciate our work? Does it seem to be a well-organized competition? Nothing is more frustrating than to go through a competitive process and feel that you are not treated well — you are doing a huge amount of work for little or no compensation. Even going into it with the assumption, ‘We’re not going to win,’ you still want to feel like you are going to be well treated.

Earl Shapiro Hall, UC Labs School, Chicago, Illinois Photos: ©Barbara Karant

COMPETITIONS: You have also participated in competitions that have not been very transparent and ended on a sour note for you. The school competition in Milwaukee is one example.

VALERIO: That was a competition we entered solely because we knew and had great respect for the competition organizer, Thomas (Mac) Slater. We had a lot of questions going into that competition, but responded because of a friend. It seemed to start well. But symbolic of what was going to happen — a few weeks before the submission was due — we got a direct phone call from the head of the building committee. ‘Why are we getting this phone call after we were told only to contact the competition adviser, Mac Slater?’ All I can say is, it all went downhill from there. By the time it all started unraveling, we were way into it: We had added staff, produced drawings, etc. It’s representative of what can happen when the client doesn’t work through the professional adviser. It just throws everything into turmoil. That’s what happened in this competition.

COMPETITIONS: Speaking of school competitions, you may not know about it, but your entry in the Chicago Public Schools competition a few years ago came very close to being included among the finalists.

VALERIO: I thought that the solutions that came out of that competition were really good and that it was very well run. The output was good, and I really respected the winners. The problem in Chicago is that we have had a lot of competitions, but very little has been built. I heard that the Southside site is going to be built. Everybody views the City of Chicago as a monolithic beast — where it really isn’t. When the City does all these competitions, and nothing gets built, everybody begins to ask themselves, ‘Is this for real?’ Since that competition, Chicago Public Schools have built a lot of schools. So everybody is asking, why aren’t they building the competition?

Godfrey Hotel, Chicago, Illinois Photos: courtesy Valerio Dewalt Train

COMPETITIONS You have served on peer committees which have decided important commissions — by way of competitions. How would you rate that process?

VALERIO: I am about to be a juror for one of the GSA design charrette competitions —the Greenville, South Carolina courthouse. I’ve served as a peer reviewer for the Jackson Mississippi courthouse, which was not a competition. Then I served on the peer review panel after Koetter Kim had been selected in a competition to do the Rockford courthouse. So I wasn’t on the jury that selected Koetter Kim, but I was on the peer review group that followed the design as it developed. In the Rockford case, I saw the competition entries, but wasn’t in charge of selecting them. Really, the GSA is faced with a really tough situation when it comes to their competitions. They generally do competitions for courthouses, which are their premier building type. The courthouse is usually under the head judge. I have met a number of these people. They are generally nice lawyers, distinguished gentlemen, and their view is that a courthouse has lots of steps and stone columns. There are very few that are interested in modern design of any kind, much less any kind of design which we might consider to be ‘breakthrough.’

Ed Feiner(GSA) has accepted the challenge and is trying to move the architecture of these buildings in the public domain from mediocre to excellent. His biggest problems are with the courthouses, for you have the court as an active player in the selection process. The competition process is used, in my view, to try to convince the judge that adventuresome design really has some value. The judges really don’t want to be put in a position where they feel like they are being backed into a corner. So the result is, when you submit a design, the design is officially being submitted to help the GSA in the selection process. It’s not the design for the building. When Koetter Kim was selected for the Rockford courthouse, there was the design, it had all the courtrooms, it had everything laid out. Then we got into this process where I was at 4-5 meetings. Immediately at the first meeting after the initial selection, Fred Koetter had to present three alternative designs. The idea was, one could be the competition entry, but then you had to have two others that were really other design concepts. You immediately got into this process where the winning design just becomes one of three on the table. Then you go through the whole development process with the judge. In the end, the final design of that courthouse is much better than you would have ever gotten if you hadn’t done the competition. But the competition entry is probably a better building. The competition becomes the sacrificial lamb. If the thing that gets pushed off the table, and what stays on the table is probably a better building than what you would ever have gotten, but it is not the competition entry. With the given circumstances, Ed Feiner has done an excellent job.

COMPETITIONS: Compared to the European model, American competitions seem to suffer from a latent distrust that officials here often harbor towards the design community. They invariably insist that they be well represented on juries — the WTC planning competition was a good example of this. Any chance we will be closer to the European model someday?

VALERIO: The tendency here is to say, in America the clients are terrible, and they don’t appreciate good design. I think the clients in Europe are as conservative as they are here in the U.S. But in Europe there is a much greater sense of community compared to the U.S. Here a public official like these judges operate from the principal, ‘I know best.’ I find this to be universal, whether you are working for a doctor on a house or for a corporate executive on a corporate structure, or an institution with an executive director or president, or a head judge. In Europe, it’s a different kind of mentality, where the leadership looks around and says, ‘what should we be doing?’ It’s a broader view of the community; and when you have a broader view of the community, you have more self-doubt. You are then more willing to put this in the hands of a group of professional jurors than you would be in the United States.

Are we going to ever move away from that idiosyncratic approach in judging design to a more community oriented approach? That is the real problem, and I haven’t seen any evidence that there is going to be that movement. Even when you have the very best design being done in the U.S., it quite often is being based on that idea of that idiosyncratic self-centered view of the world, it’s just that that person happens to like more adventuresome, more radical design.I find the orientation of the decision-makers in the United States being dramatically different from the orientation of the decision-makers in Europe.

COMPETITIONS: When did you decide you wanted to become an architect? Where did the encouragement come from?

VALERIO: I decided I wanted to be an architect when I was a freshman in high school.

COMPETITIONS: Was it some building you saw?

VALERIO: It is one of those decisions you look back on, especially because I made it so early. I can’t remember why I made it. It was probably had more to do with the fact that when I was really young, I was always interested in building things, whether it was building model airplanes or building stuff around the house with my father. It was more of a desire to build. My dad was an electrical engineer, and I remember asking him about how things got built. He knew the process and explained that the guy who leads the team is the architect. So it’s the guy who controls the process — although we know that is not really true! So it didn’t have anything to do with any particular building.

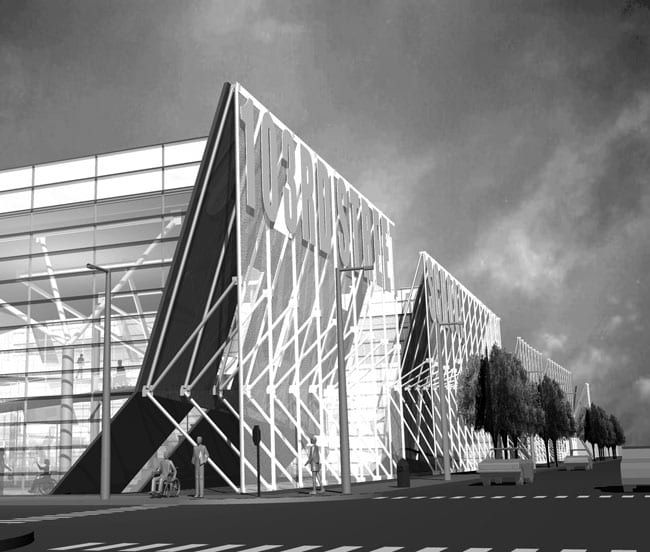

Kresge Foundation Headquarters, Troy, Michigan (2002-) Photos: courtesy Valerio Dewalt Train Associates

COMPETITIONS: How did your eBay commission happen?

VALERIO: There is a direct line which I can trace through a whole series of people — it went from the U.S. Robotics assignment in 1993 all the way up to being hired by eBay in 2003. When we initially got hired by them — and this is the only time it has happened to us — they hired us based on our reputation, a traditional process. They work with a lot of different designers, and those designers didn’t have a very long shelf-life with the company. We said to them very early on, ‘What are you trying to achieve?’ Yes, we are building buildings and space for you; but what is the objective? Their reply was, ‘Don’t ask those questions; our staff is expanding; we need more seats. Just build the stuff.’

We told them, ‘You really ought to think about this; we should talk about how the space works and really what it looks like.’ What we said was, ‘let’s engage in a real dialogue about the aesthetics of your space.’ It’s something we often tend to bring up with clients, because clients don’t expect that of architects. They expect architects to come in with a design. They sit down and say, ‘We like it,’ or ‘We don’t like it.’ The architect says some mumbo-jumbo about something, and the design somehow gets built. There’s not much of a dialogue between the architect and client. We feel that is not the way to do it. There ought to be an actual dialogue.

eBay Headquarters, San Jose, California (2002-) Photos: courtesy Valerio Dewalt Train Associates

We eventually edited it down to a cluster of photographs which went from concept to actual spatial photos of real architecture. They presented that to a group of senior executives, who further edited it before it was presented to CEO, Meg Whitman. That study is now the basis for the future design which is now moving forward, because Meg finally got an opportunity to focus in on what she thought an eBay environment really should be — both in conceptual and physical terms. So this was a process which we have become involved in with other clients. Many are hesitant about this. They are much more comfortable talking about work surfaces, how big desks should be, and where buildings should go — these very practical, functional questions. Most clients aren’t really prepared to talk about pure aesthetic questions. Through this process, we try to get them involved in that, so when you finally come up with a building design, there are some anchorings you can tie into, like ‘we all agreed that you wanted large windows,’ because that expressed the openness of the corporation. That is how we approached eBay.

COMPETITIONS: Most people only visit eBay on their personal computers.

VALERIO: There was a method involved to getting Meg involved in this. She couldn’t talk to every new employee, which used to be the case. So we wanted to express the culture of eBay through the physical environment, to express the values she felt everybody should be buying into who worked for eBay. So we did this based on the idea of creating an environmental experience which would lead the employee to reach a better understanding of the company. When companies grow like this, the first one hundred employees have a strong relationship to the CEO. After that it just trails off, until you get people there who are asking, where am I; where’s my paycheck, etc.? We wanted to expand that experience so that new people — there are a hundred new people showing up every month — they look around and say, ‘We get it.’