Playing the China Card: The MRY Example

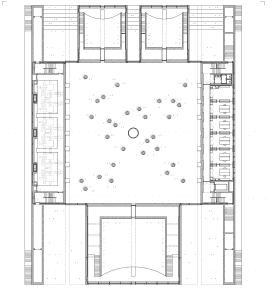

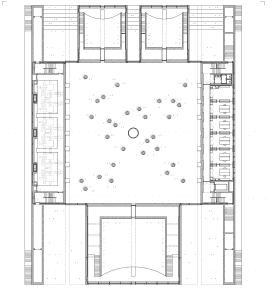

Chun Sen Bi An Housing, Chongqing (competition 2004; completion 2010)

COMPETITIONS: Moore Ruble Yudell (MRY) has had a reputation as an international player since the 1980s. How did you manage to become involved in China? James O’Connor: We were first invited to take part in a (developer) competition in Beijing in 2002, the Beijing Century Center. We won, but the project was never built. The client was not that serious, and we never got paid. After that, we said that we would never enter another competition in China. But, what turned out to be a real clientele kept after us to participate in one of their projects. After turning them down several times, we finally relented. That was a competition for the Tianjin Xin-he New Town Master Plan and Housing in Tianjin—which we did win.

Chun Sen Bi An perspectives (above)

Chun Sen Bi An Housing Master Plan

COMPETITIONS: Once you have become established in China, it would seem that you almost can pick and choose between competitions and projects. O’Connor: Right before the time of the Olympics, there were few foreign firms working there so we were interviewing clients as opposed to clients interviewing us. And every time we would go out, we would be involved with another project, or another competition. It all started in kind of a shaky way; but that’s kind of how it evolved. Read more…

333 Wacker Drive – view with Chicago River in foreground (photo: ©Barbara Karant)

COMPETITIONS: When you are called on to design a ‘foreground’ building for a corporate client—although it’s usually an office building, it could be any number of building types—how do you balance the private and public interest beyond the usual zoning regulations?

left and below

Gargoyle Club Prize

Best Architectural Thesis, University of Minnesota School of Architecture (1961)

Theme: Hospital Project

Images: courtesy William Pedersen

Pedersen: The interest of the client as it relates to the quantity of the construction they wish to place on a site is perhaps the most difficult issue, particularly during the 80s, when a tremendous amount of construction was taking place in the United States, and one more office building was not hailed by anybody as a contribution to society. The situation has changed rather dramatically in the 90s, when almost none of them are being built; so the issue is not as pressing. But there always is the question, ‘Is a building, given the bulk proposed, appropriate for its specific condition?’ One’s ability to deal with that issue is somewhat limited because zoning establishes what is of right, and not of right. Therefore, the battle has largely been fought prior to our entrance on the scene. Past that point, the relationship of our buildings to a specific context has been a fundamental issue of our architecture. This is particularly how we take tall buildings, which are in themselves somewhat insular, autonomous and discrete, and bring them into a more social state of existence. That’s been the subject of our study for the last twenty years. We’ve developed strategies for doing that, of which I’ve spoken at length. The preoccupation of making the tall buildings—part of a more continuous, overriding fabric—that’s been central to our architecture. COMPETITIONS: The most obvious argument against contextualism—as many people understand it—would be the Pompidou Centre in Paris, which has turned out to be the most visitied and popular building in that city. Wouldn’t that seem to give architects a good argument for doing something different? Was that even a lesson? WP: Juxtaposition is a fundamental contextual strategy; but it has to be used sparingly and has to be introduced at exactly the right moment for it to have a powerful effect. For example, the Seagrams Building on Park Avenue—before any of the other buildings followed suit—was exceedingly powerful and very successful as a result of the juxtaposition at that particular place. I would argue that our building in Chicago (333 Wacker Drive) is an equally successful contextual building. It’s on the only triangular site of the Chicago grid at a bend in the Chicago River, and it sits within a context of totally masonry buildings, largely of the classical derivation. Somehow the relationship between those very distinct parts works. We were asked to build a building right next to 333 Wacker Drive, which did not occupy a unique geometric piece of property, but in fact became more of a continuation of the street wall leading up to 333 Wacker. We elected there to utilize a more Classical language in total juxtaposition to our own 333 Wacker in an effort to try to achieve the continuity of the wall that we thought was necessary, but also to maintain that poignancy of a juxtaposition to 333 Wacker Drive to the rest of the context. It would weaken it tremendously if it had been reproduced next door. The same is true of the Pompidou Centre. If one were to tear down that section of Paris around it and build a number of Pompidou Centers there, it would lose its impact, because ifs impact is an object set within a very careful framing in that traditional neighborhood. Without the dialogue between the two, the game is over.

AAL Hqs. building addition (1971), Appleton, Wisconsin

AAL Hqs. original building

AAL rendering

COMPETITIONS: Most people seem to believe that 333 Wacker is the best building you have done. Maybe it was the time and unique site. It was one of those projects where one announces, ‘Well, here I am.’ Sometimes it’s difficult to top a wonderful building like that, though you may believe your next building is the one you like best. WP: I think that 333 was a product of my sensibility at that point in time. It was a building that tended tobe an intuitive response to the site. In terms of it language, it came out of a couple of other buildings I had done immediately prior to that—one being the Aid Association for Lutherans in Appleton, Wisconsin, the other being the Brooklyn Criminal Courts Building, which had very similar geometric ideas in terms of its relationship to context. The very conscious attitude of trying to make the tall building part of a larger urban contet preoccupied us for the next five years. As a result, we used a more classical language to try to develop connecting strategies, because a Classical language is largely built on ideas of connection of pieces and parts, one to another…buildings connect well because they have parts that are combined and are part of a central language. Read more…

with Stanley Collyer

Bundeskanzleramt Berlin Competition (1996); Completion (2000) Photo: courtesy Schultes Frank Architekten

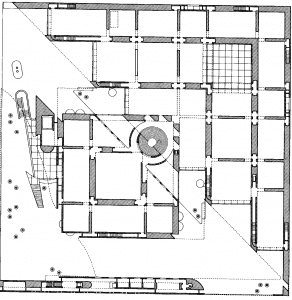

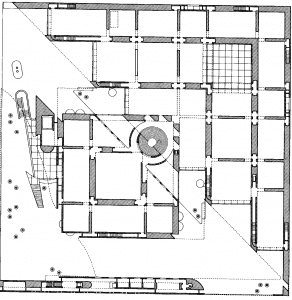

COMPETITIONS: In our last conversation, we talked about the whole issue of Berlin’s identity and what approach one should use in reconstructing the urban fabric between East and West—where the wall used to be. Axel Schultes: Maybe I learned something during a recent lecture I gave in Palermo (Italy). Afterwards, some German specialists in philosophy and German thinking—brilliant people, I must say—came up to me and said, ‘What you said about Berlin and what you are doing there with the Federal Chancellery (Bundeskanzleiamt), for us is what Ernst Bloch and Walter Benjamin talked about, especially when they looked at Italy and the cities in Italy. We noticed immediately in your work that (same) issue of porosity.’ Both used this term: Benjamin wrote a small article on Naples, and Bloch wrote about Italy as a whole. We always had a tendency to avoid the term, ‘transparency.’ Transparency is usually the use of glass to make buildings less alienating to someone outside. But for us, glass is no material to create spaces; so transparency as we see it is depths of spaces or layering. Porosity is something much more precise—what we strive for. We wanted the same effect in Friedrichstrasse (Interior Mall): it should not be this close-up thing of the Galeries Lafayette (Jean Nouvel) or Ungers, where you only have some holes in it. Porosity for us is like a sponge—to enable a building to fill up with life, to turn a private space into a public one by penetrating it with a public space. The old buildings in Berlin are examples of this, with two, three, sometimes even four interior public spaces.

Berlin Baumschulenweg Crematory (1993)

COMPETITIONS: You are referring to the interior courtyards (Hinterhöfe)? AS: Yes. Nothing of this sort exists anymore in Berlin. Most buildings (at the street) are flat, sometimes elegant, sometime ugly. The Galeries Lafayette, with all its glass, is as closed (to the outside) as one of Unger’s sandstone buildings. It’s the same issue in the construction of every building. Take, for instance, the Berlin Schloss (the palace in the center of Berlin), which was completely demolished after WWII, and which some people think should be resurrected. This has been on our mind constantly.* It would be such a contrast to urbanism—needing to punch holes in it to get inside—open to all the people and all walks of life. I can give many examples of this, for me very northern, very restrained, very alien to everything which infuses a culture with life. All the people here like Kohlhof, Ungers, Kleihues, etc.; all have that tendency of closing. Even Libeskind—and maybe he doesn’t think about it or want to have it appear in such a manner—does it with the Jewish Museum where there is no penetration. There is always this hiding, this animosity to the urban fabric. They are not interested in breaking it up.

Bonn Art Museum – Competition (1985) Completion (1992) Read more…

Nara Convention Center Jurors James Stirling with Jorge Glusberg (right)

GLUSBERG: What do you feel are the basic components necessary for good design? STIRLING: I think every building must have at least two good ideas. I don’t see the design process as a sudden blinding flash of insight. That might be true for a structure that has one main purpose, like a stadium or an office building; but, in my opinion, it won’t work with a multi-functional building. That, in fact, is what most of the projects in our office tend to be. GLUSBERG: Then how would you describe your process? STIRLING: We really try to be careful and conscientious in our analysis. We work in a very linear fashion so that the final design reflects the path of decision-making. GLUSBERG: You just said that few of your buildings have a simple program: but what about the Science Center in Berlin?

Berlin Science Center (photos: Stanley Collyer)

STIRLING: Yes, you’re right. That is an office complex, but it also incorporates an existing Beaux Arts building that was remodeled into several lecture halls. In the office building we had to provide three hundred similar offices for researchers. We were looking for an architectural solution, rather than for a solution to the program which would have been very repetitive. So we created a group of five adjoining buildings surrounding a courtyard. The space between the administration, the sociology and the environment departments, the library, and the archive helped us to overcome the monotony of the program. Read more…

Cover of the 1997 Fall issue of COMPETITIONS (left), showing the phase one completion of Erickson’s University of British Columbia Library. Photo: Stanley Collyer

Vancouver Civic Center/Robson Squre (right) Photo: courtesy Arthur Erickson

Read more…

COMPETITIONS: you have been in both open and invited compe-titions—both as a juror and as a participant. Which type do you prefer and why?

RALPH JOHNSON: I think both are viable. For a young architect, open competitions are great, because they are not going to get invited. It’s a way for young architects to break into a bigger scope of work. It’s an oppor-tunity for someone who doesn’t have the experience in that particular building type to get into a new area.

Shanghai Natural History Museum Photos: courtesy Perkins and Will

An invited competition usually involves some kind of portfolio or resume of the firm’s work, and you usually get selected on experience in that particular building type. In the latter case, you are probably dealing with fairly extensive presentation requirements and a big outlay of money. It often also involves a couple of stages. If the compensation is adequate, which is usually six figures—$100,000-$200,000—it’s great. Most of the time, it’s inadequate. For the recent (Beirut Conference Center) competition, we did in Lebanon, it was $200,000, and that was enough to cover (our) costs. So there are benefits for both types of competitions. COMPETITIONS: And as a panelist? RJ: It’s much more difficult to jury the open ones because it takes longer. I was on the Astronaut Memorial jury, and there were over 600 entries. You normally don’t interview the architect; it’s single-stage. It’s more a process of winnowing out inadequate submissions—which is easy to do—and getting down to the ten percent after the first cut. In the case of an invited competition, you have five to ten submissions from very qualified firms. I think it’s good if you can actually interview firms and have a question and answer period. In an open competition, it’s almost inevitable that you wonder who is actually doing the project, how qualified the architect is. It’s hard to keep that out of your mind.

Shanghai Natural History Museum Photos: courtesy Perkins and Will

COMPETITIONS: In other words, the presentation isn’t necessarily an indication of the qualifications of the designer? RJ: I wasn’t on the jury in the case of the Vietnam Memorial, which was a famous competition. There were very sketchy charcoal drawings (by Maya Lin), which really didn’t indicate anything other than conceptual design capabilities. How could you possibly come to any conclusion of technical competence based on those drawings? You really have to read into it and assume a lot in terms of the person. In that case, of course, it was a great success as a non-complex building type. As a laboratory or something else, it’s a different story. COMPETITIONS: There are a number of anecdotes concerning jurors speculating about the author behind a competition entry—the one in Paris resulting in the Grand Arch is an example. Richard Rogers, a competition juror, supposedly remarked to another juror, Richard Meier, that the author of what eventually turned out to be the winning design, “might be a nobody.” Meier reminded Rogers that, before Pompidou, he was a “nobody.” Read more…

North Point Competition model, Cambridge, Massachusetts (2003) COMPETITIONS: As has been case with many architects, your career got a very big boost by virtue of winning a competition — Colton Palms Senior Apartments. Was that the very first competition you participated in? VALERIO: No. It wasn’t the first, and it wasn’t the Read more…

with George Kapelos Swansea Literature Center (competition 1993) KAPELOS: What led you to architecture? ALSOP: I want to start by saying that I never remember not wanting to be an architect. Why that should be I have no idea. I grew up in England in Northampton near a Peter Read more…

Miami Performing Arts Center with Sears Tower in center; Competition (1995), Completion (2006) COMPETITIONS: What was the first competition you participated in? PELLI: I believe the first was during my third year in school as an undergraduate. It was a sketch competition for completed designs. It was run by Ernesto Read more…

Seattle Olympia Park Sculpture Gardens – opening day (photo: Ben Benschneider) COMPETITIONS: What were the main program challenges you had to solve in designing the Seattle Sculpture Park? The project is now in the development phase (2003); so has your approach changed somewhat, or are you sticking pretty much to your original Read more… |

1st Place: Zaha Hadid Architects – night view from river – Render by Negativ

Arriving to board a ferry boat or cruise ship used to be a rather mundane experience. If you had luggage, you might be able to drop it off upon boarding, assuming that the boarding operation was sophisticated enough. In any case, the arrival experience was nothing to look forward to. I recall boarding the SS United States for a trip to Europe in the late 1950s. Arriving at the pier in New York, the only thought any traveler had was to board that ocean liner as soon as possible, find one’s cabin, and start exploring. If you were in New York City and arriving early, a nearby restaurant or cafe would be your best bet while passing time before boarding. Read more… Young Architects in Competitions When Competitions and a New Generation of Ideas Elevate Architectural Quality

by Jean-Pierre Chupin and G. Stanley Collyer

published by Potential Architecture Books, Montreal, Canada 2020

271 illustrations in color and black & white

Available in PDF and eBook formats

ISBN 9781988962047

Wwhat do the Vietnam Memorial, the St. Louis Arch, and the Sydney Opera House have in common? These world renowned landmarks were all designed by architects under the age of 40, and in each case they were selected through open competitions. At their best, design competitions can provide a singular opportunity for young and unknown architects to make their mark on the built environment and launch productive, fruitful careers. But what happens when design competitions are engineered to favor the established and experienced practitioners from the very outset? This comprehensive new book written by Jean-Pierre Chupin (Canadian Competitions Catalogue) and Stanley Collyer (COMPETITIONS) highlights for the crucial role competitions have played in fostering the careers of young architects, and makes an argument against the trend of invited competitions and RFQs. The authors take an in-depth look at past competitions won by young architects and planners, and survey the state of competitions through the world on a region by region basis. The end result is a compelling argument for an inclusive approach to conducting international design competitions. Download Young Architects in Competitions for free at the following link: https://crc.umontreal.ca/en/publications-libre-acces/

Helsinki Central Library, by ALA Architects (2012-2018)

The world has experienced a limited number of open competitions over the past three decades, but even with diminishing numbers, some stand out among projects in their categories that can’t be ignored for the high quality and degree of creativity they revealed. Included among those are several invited competitions that were extraordinary in their efforts to explore new avenues of institutional and museum design. Some might ask why the Vietnam Memorial is not mentioned here. Only included in our list are competitions that were covered by us, beginning in 1990 with COMPETITIONS magazine to the present day. As for what category a project under construction (Science Island), might belong to or fundraising still in progress (San Jose’s Urban Confluence or the Cold War Memorial competition, Wisconsin), we would classify the former as “built” and wait and see what happens with the latter—keeping our fingers crossed for a positive outcome. Read More…

2023 Teaching and Innovation Farm Lab Graduate Student Honor Award by USC (aerial view)

Architecture at Zero competitions, which focus on the theme, Design Competition for Decarbonization, Equity and Resilience in California, have been supported by numerous California utilities such as Southern California Edison, PG&E, SoCAl Gas, etc., who have recognized the need for better climate solutions in that state as well as globally. Until recently, most of these competitions were based on an ideas only format, with few expectations that any of the winning designs would actually be realized. The anticipated realization of the 2022 and 2023 competitions suggests that some clients are taking these ideas seriously enough to go ahead with realization. Read more…

RUR model perspective – ©RUR

New Kaohsiung Port and Cruise Terminal, Taiwan (2011-2020)

Reiser+Umemoto RUR Architecture PC/ Jesse Reiser – U.S.A.

with

Fei & Cheng Associates/Philip T.C. Fei – R.O.C. (Tendener)

This was probably the last international open competition result that was built in Taiwan. A later competition for the Keelung Harbor Service Building Competition, won by Neil Denari of the U.S., the result of a shortlisting procedure, was not built. The fact that the project by RUR was eventually completed—the result of the RUR/Fei & Cheng’s winning entry there—certainly goes back to the collaborative role of those to firms in winning the 2008 Taipei Pop Music Center competition, a collaboration that should not be underestimated in setting the stage for this competition Read more…

Winning entry ©Herzog de Meuron

In visiting any museum, one might wonder what important works of art are out of view in storage, possibly not considered high profile enough to see the light of day? In Korea, an answer to this question is in the making. It can come as no surprise that museums are running out of storage space. This is not just the case with long established “western” museums, but elsewhere throughout the world as well. In Seoul, South Korea, such an issue has been addressed by planning for a new kind of storage facility, the Seouipul Open Storage Museum. The new institution will house artworks and artifacts of three major museums in Seoul: the Seoul Museum of Modern Art, the Seoul Museum of History, and the Seoul Museum of Craft Art.

Read more… |