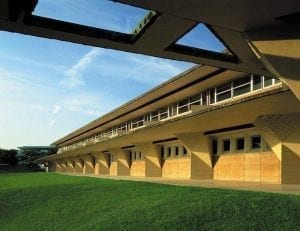

Carroll A. Campbell Jr. Graduate Engineering Center, Clemson University (Photo: ©Tim Hursley)

Carroll A. Campbell Jr. Graduate Engineering Center, Clemson University (2004) Rendering courtesy Scogin Elam

COMPETITIONS: You were both working for a very successful, large architecture firm in Atlanta when you decided to go off on your own. How

Read more…

COMPETITIONS: I am presently here in London to talk to my editor about a ‘how to’ book we are doing on competitions.

JOHN MCASLAN: And how not to do them, I hope.

COMPETITIONS: You’re familiar with one of those?

JM: We recently did one—Middlesborough Town Hall. It caused a real furor here.

COMPETITIONS: Usually the RIBA competitions are well organized.

Science Center, Florida Southern College (1996-2001)

JM: This was an open, non-RIBA competition to re-market (rebuild) the Town Hall in Middlesborough, a town which had quite a good artistic tradition. About ten years ago they commissioned Claes Oldenburg to design a sculpture. There was also a competition for a museum there—which we didn’t get. And then there was the competition for the Town Hall, where we got to the last six. It was chaotic, as to what was to be submitted. There was a lot of to-ing and fro-ing, because the terms of reference weren’t clear. And then there were long delays before the interviews. Finally we were asked to submit a tender(fee bid). But of the six tenders, only four arrived on time. Because of that, the two late tenderers were eliminated. I thought, ‘well, you know you have to get them in on time.’ But then one of the jurors walked out, because she thought it unfair that these two had been eliminated. Then it came out that they had opened the bids before the interviews took place.

We were only runners-up; but the whole thing has caused chaos because of the sloppiness with which the whole thing was organized. They should have selected the preferred team , then opened the bids.

You asked about the RIBA competitions. We have won some and lost a some. But you can say that they are always immaculately organized—very transparent, no confusion over what is required when. If a competition is badly administered with lots of criticism, it doesn’t help at all, especially with funding.

Science Center, Florida Southern College (1996-2001) Lab interior (left) and model (right)

COMPETITIONS: You were recently in the Fresh Kills competition in the U.S.

Read more…

COMPETITIONS: I assume you attended sessions during both stages of the competition, How long did they last?

Michael Sorkin: I think they were both a couple of days each. At the second session there were presentations by the teams, which were long enough. It was very professionally and equitably organized.

COMPETITIONS: Although the competition brief was only 29 pages, I thought it was one of the best documents of that type I have come across.

MS: It was very succinct and well done. I have been involved with the people who were engaged in the organization of the competition before, and there was a very high level of competence.

COMPETITIONS: As for the jury, was it about the right number?

MS: It was a very congenial group. There was no violence, but there was a good discussion. Everybody was looking for a good outcome, and we did end up picking one of the most visionary schemes submitted. I would say that in terms of the way that the projects progressed from the shortlist to the final presentation, these people (the winner) did an extraordinary job. Theirs was the scheme that was the most thoroughly mature in that process.

Read more…

COMPETITIONS: Was this your first time in Moscow?

KS: Each trip was so short, and we were actually cocooned in the Strelka institute and the area around Red Square during that short stay, so that we hardly had time to see anything else.

COMPETITIONS: What was your take on the Zaryadnye Park competition site?

KS: The site was fantastic. It’s right in the heart of Moscow, adjacent to a historic neighborhood, and on the other side to Red Square and the Kremlin. So there probably wasn’t a more significant site in the entire city. And it was a huge site—formerly the site of a huge hotel.

COMPETITIONS: You were there for two sessions. How far apart were they?

KS: The first session was in June in what was perfect Moscow weather. The jury convened to go through what seemed like a hundred submissions, which teams submitted with their credentials. We spent two days going through those. We reconvened in November for what was the final jury. So we also got the beginning of the Moscow winter on that trip, which gave us an idea of the seasonal change. At that time we reviewed the proposals of the six entries we had shortlisted, and saw the videos they had submitted. The teams did not present in person. The video presentations were quite sophisticated, and they had to have spent a lot of money on them. They were very good.

COMPETITIONS: The composition of the jury was interesting. Did most of the discussions take place in English?

KS: Everything was in simulcast translation. We always had our headsets on, so even when somebody was speaking in Russian, you would get the simultaneous translation. So it worked pretty well.

COMPETITIONS: I see that Peter Walker was also a juror.

KS: He was not there for the first session, but was there for the final meeting.

COMPETITIONS: It was a rather large jury. Was it somewhat unwieldy because of the size?

Read the article

Read more…

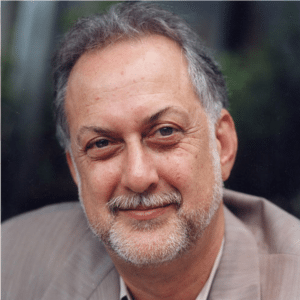

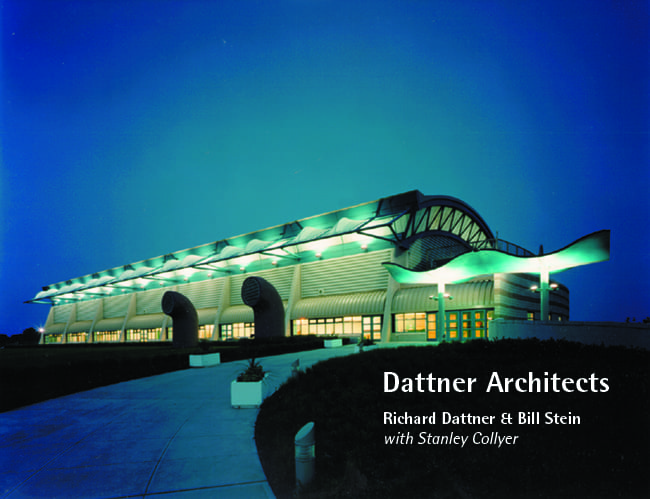

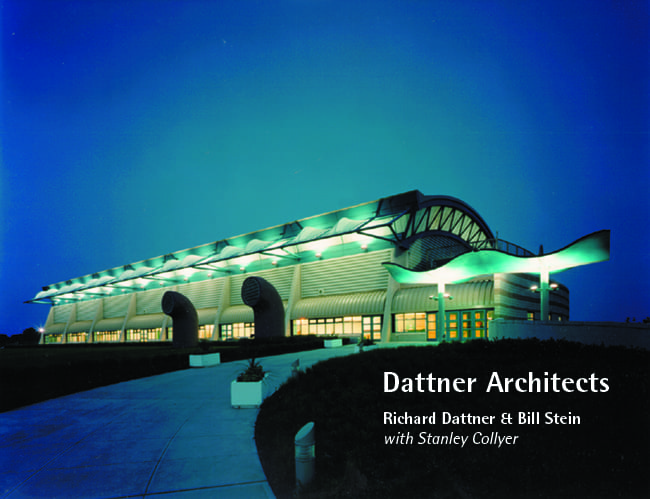

with Stanley Collyer

Mumbai City Museum Competition Winner (2014)

COMPETITIONS: What was the first competition you ever participated in?

HOLL: I did a competition in 1972 for the Niagara Falls Rainbow Plaza Gardens—which I did in my bedroom in San Francisco. I had just graduated from the University of Washington and had moved to San Francisco, where I was working for Backen Aarigoni and Ross. I think I got fourth place, or something like that in that competition, and it gave me incredible encouragement to proceed in my own design work. It was published in architecture plus by Peter Blake. The article was called “Back from Niagara.” That was the first time I ever got published.

COMPETITIONS: The last time we met you had just returned from San Francisco, where you came in a very close second in the San Francisco Mission Bay planning competition (COMPETITIONS, Vol. 8, #2). You teamed up with George Hargreaves, a landscape architect who is not known for just filling in the blanks.

HOLL: Whenever you go after a competition, you try to put the best team together and envision winning it. I thought that George would be a great collaborator out there in San Francisco—he lives on a hill which overlooks the Mission Hill project—I thought that if all things went well, he would be the best person to work with. We collaborated back and forth by fax and met a few times. I think he was very partial to some of the ideas we had; he helped us to develop them. There was a good back-and-forth going on.

COMPETITIONS: I understand that one of the major concerns of the jury was phasing, since the plan could not be realized all at once. One member of the jury characterized the first phase as “brilliant.”

HOLL: I thought our phasing scheme was very good—and this was George’s idea—in the sense that we could landscape and make an incredible public space in the first phase. I thought it was the strongest part of our scheme. I think one has to look at it carefully to understand it. That was actually the strongest part of our scheme.

Holl model (upper left) for Glasgow School of Art Competition (2009); Completion (2013)

COMPETITIONS: Many of your recent projects have been additions to buildings—Cranbrook, Pratt Institute, the University of Minnesota School of Architecture. Additions can be almost like infill; but in other respects, a question may arise, as in Cranbrook, as to how much you may feel obligated to defer to Saarinen’s design. How does the existing architecture play a role?

Read more…

with Jerzy Rosenberg

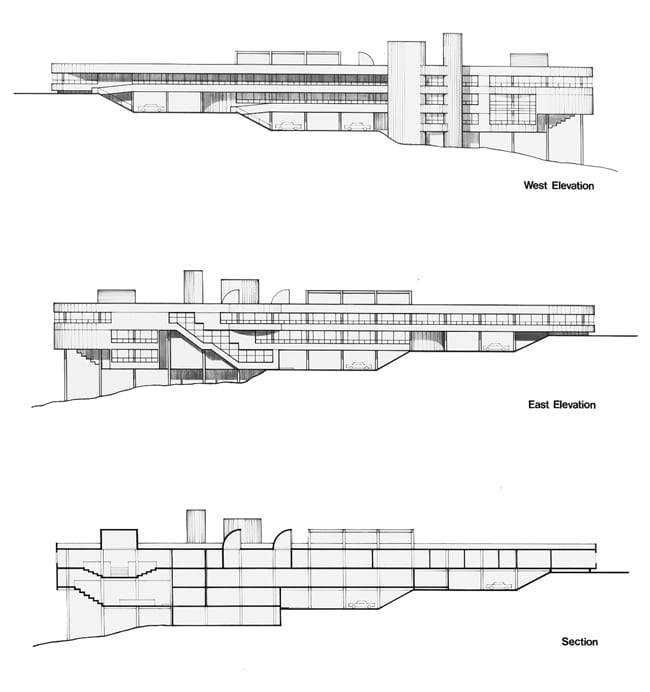

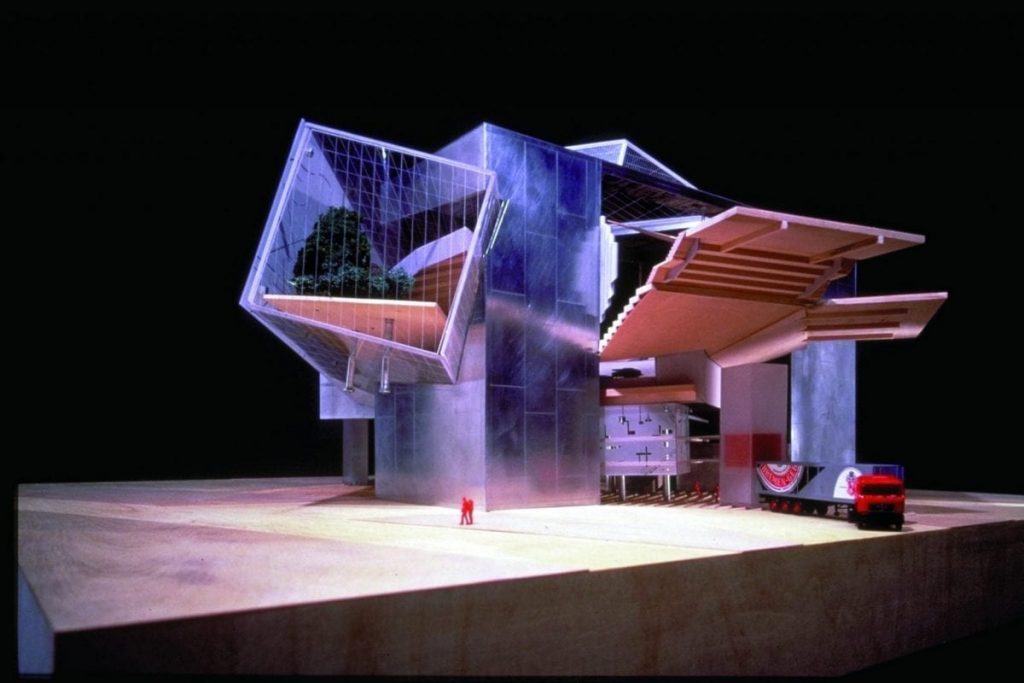

Bremen Philharmonic Hall Competition, Bremen, Germany – First Place (1995)

COMPETITIONS: Among the leading architects in the world, you may be unique in that everything you have built came about exclusively through competitions. Consequently it would be interesting to hear you view on competitions, and in particular whether you think it is still a viable form for young architects’ participation in the making of architecture.

LIBESKIND: It is a great form to work with; I probably would never have had any practice without competitions. But the nature of competitions is changing. In fact, now that the competitions are being globalized, they are becoming less of a form and forum. With globalization and the consequent bureaucracy, comes the opposite effect— a fragmentation and regional control by power brokers. It is now less possible to have an independent choice by competition because there are more networks which are involved.

COMPETITIONS: What is the earliest competition that you recall participating in?

Read more…

Goodwill Games Swimming and Diving Complex, New York, NY (Photo: Peter Mauss/ESTO) Goodwill Games Swimming and Diving Complex, New York, NY (Photo: Peter Mauss/ESTO)

COMPETITIONS: What led you to choose architecture as a profession?

RICHARD DATTNER: It’s a little like Dustin Hoffman in the movie The Graduate. I already wanted to be an architect in the seventh grade, when I was building architectural models. When I was in high school, somebody whispered to me “electronics.” “Since architects don’t make money, you should study something that has a real future.” So I actually went to MIT thinking I would become an electrical engineer. I realized you couldn’t see any of those little things zipping around—the electrons, etc. My next door dorm-mates, actually three architects from New York,–Andy Blackman, Peter Samton and Jordan Gruzen, were three years ahead of me and were having a lot of fun—building models, beautiful girls came in and out of their dormitory rooms. I thought, “I’ll have what they’re having.” Luckily, at MIT, the first year is the same for whatever your major will ultimately be; so I switched back to my original love. From there, I never looked back.

COMPETITIONS: MIT was different than Harvard when you were there. At Harvard, where they had very strong deans—Gropius and Sert—everything that the students turned out looked pretty much the same. At MIT it was different.

RD: MIT was a kind of ‘Let a Hundred Flowers Bloom.’ They had some wonderful people, some of whom were rejects from Harvard, .i.e. Joseph Hudnut, who had been the dean at Harvard. Other great professors included Lewis Mumford, Kenzo Tange, Leonardo Ricci, Georgy Kepes, Richard Filipowski, Lawrence Anderson, etc.

COMPETITIONS: What effect did your stay at the Architecture Association in London have on you?

RD: During my junior year at MIT, I had an opportunity to take the middle year of my 5-year stay at MIT at the AA. There I had a similarly interesting roster of people—James Stirling and many of the British “brutalists.” It was a good antidote to America. In those days in America, Edward Durrell Stone was the hero, producing a kind of “surface architecture,” which by the way is probably going on today. So what goes around, comes around. When I was in London in 1957/58, London was still recovering from the war—there were still bombed-out sites. So architects were much more brutal and honest—Corbusier was a hero. The London County Council was doing incredible social housing, some of it based on the Unité d’habitation of Corbu. There was a lot of fascinating school design going on. As an interesting time, it was a real kind of antidote to the postwar, feelgood (trend) then current in the United States.

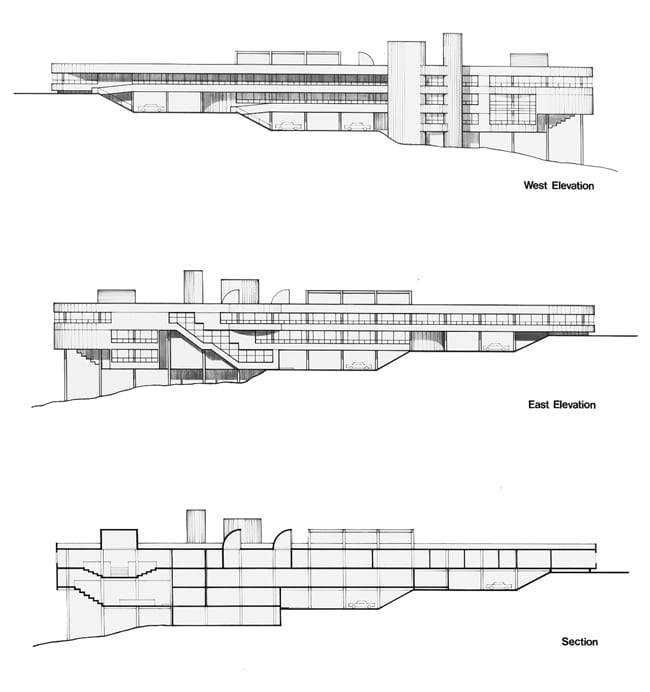

Courtlandt City Hall, Courtlandt, NY – Winning Competition entry, 1976 (unbuilt)

COMPETITIONS: When you started your own firm in New York, you were doing a lot of playgrounds. Is there some kind of logical progression from that genre to designing schools?

Read more…

Interview with Stanley Collyer

FIU School of Architecture, Miami, FL, 1999-2003 (© Peter Mauss)

Read more…

Interview with Steve Wiesenthal, University of Chicago

Campus Architect

with Stanley Collyer

Finalists clockwise from top left: Studio Gang, Perkins and Will, Hopkins Architects, BIG

ÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ

COMPETITIONS: Based on past and recent history, the University of Chicago seems to be concentrating on exceptional design. Just being in Chicago might be one reason; but you have instituted a competitive design process. How did this come about?

STEVE WIESENTHAL: For every project we undertake, we do an in-depth analysis about the best delivery process, the types of architects we think might be best for those types of projects, and, in the case of the residence hall—which is not just a residence hall, but dining commons, some class rooms, and some other community-type spaces—we had a pretty good idea programmatically what we wanted. The site is on the edge of campus and had on it a 1962 residence hall that was pretty much a fortress up against the surrounding community in Hyde Park. At the primary intersection of campus and community, there was a loading dock and a giant brick wall. We saw this site as an opportunity to dramatically change the relationship between campus and community and thought that what we really wanted to find in the architectural community was ideas that would create the best college housing experience for our students and layer onto that this notion that it would completely change the experience for everybody else on the campus. It’s a big site; we actually expanded it. We incorporated what had been a practice field for our athletic program. The idea was that we create a whole new quadrangle for the campus.

Again, I don’t think I would do a design competition for a high performance physical sciences laboratory building where you want to generate the program and design in parallel. The fact that we had a clear program and high aspirations for the urban plan of this, suggested approaching architects in a competition mode.

ÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ

Read more…

with Stanley Collyer

COMPETITIONS: I’m not certain how familiar you were with previous competitions in Taiwan; but this one had much in common with previous ones, in that it was also international in format.

MARK ROBBINS: They are quite high profile for remarkably large-scale projects.

COMPETITIONS: This is similar to the others, and, like those, had two sessions. Were you able to take part in both of them?

MR: Yes. It was on Kinmen Island, which I had never been to. And it has an interesting history. First of all, the U.S. government has had to figure out the deaccessioning of the bases that were military. This is a large island that had been used for military purposes, for although it is part of Taiwan geographically, it is closer to the Chinese mainland and was shelled pretty relentlessly. But because it had been closed off to development during this period, it had a very natural environment—it has one of the highest levels of biodiversity of any area in Taiwan.

So the redevelopment of this becomes quite important, because you have an island, which is now strategically located, interestingly not for military reasons, but commercial reasons. This is expected to make it valuable because of the robust commerce between a Mainland China that still finds they can get a greater variety of consumer goods in Taiwan. Rather than flying goods in, it will be by boat, which is slower, but less expensive. So it will become a vast duty free area. And that was part of the motivation for this competition—to make a more accessible gateway for trade to and from Mainland China.

Port of Kinmen winning entry

COMPETITIONS: Biodiversity caused by the lack of development during the Cold War brings to mind a similar situation in Germany on the demarcation line between East and West, where a large restricted strip on the eastern side of the border resulted in an untouched refuge for birds and various species.

MR: One seldom thinks of that. In Kinmen there are some of the best-preserved architectural artifacts, both from the Japanese colonial period and from earlier Chinese trading families. There are a series of buildings that have neoclassical detailing, but built around traditional courtyards in a Chinese format. These were families that wanted to display their wealth in the 1800s, through symbols displayed by western architecture. Because of the Cold War period and the lack of development, these were also preserved.

Read more…

|

Helsinki Central Library, by ALA Architects (2012-2018)

The world has experienced a limited number of open competitions over the past three decades, but even with diminishing numbers, some stand out among projects in their categories that can’t be ignored for the high quality and degree of creativity they revealed. Included among those are several invited competitions that were extraordinary in their efforts to explore new avenues of institutional and museum design. Some might ask why the Vietnam Memorial is not mentioned here. Only included in our list are competitions that were covered by us, beginning in 1990 with COMPETITIONS magazine to the present day. As for what category a project under construction (Science Island), might belong to or fundraising still in progress (San Jose’s Urban Confluence or the Cold War Memorial competition, Wisconsin), we would classify the former as “built” and wait and see what happens with the latter—keeping our fingers crossed for a positive outcome.

Read More…

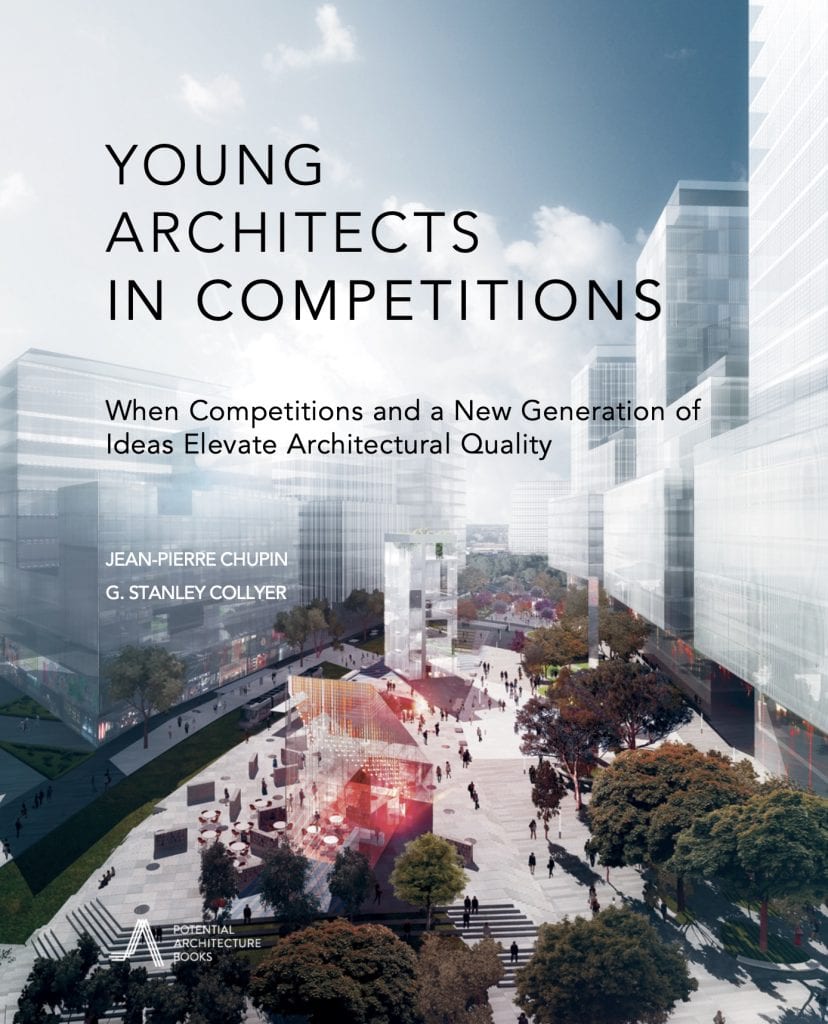

Young Architects in Competitions

When Competitions and a New Generation of Ideas Elevate Architectural Quality

by Jean-Pierre Chupin and G. Stanley Collyer

published by Potential Architecture Books, Montreal, Canada 2020

271 illustrations in color and black & white

Available in PDF and eBook formats

ISBN 9781988962047

What do the Vietnam Memorial, the St. Louis Arch, and the Sydney Opera House have in common? These world renowned landmarks were all designed by architects under the age of 40, and in each case they were selected through open competitions. At their best, design competitions can provide a singular opportunity for young and unknown architects to make their mark on the built environment and launch productive, fruitful careers. But what happens when design competitions are engineered to favor the established and experienced practitioners from the very outset?

This comprehensive new book written by Jean-Pierre Chupin (Canadian Competitions Catalogue) and Stanley Collyer (COMPETITIONS) highlights for the crucial role competitions have played in fostering the careers of young architects, and makes an argument against the trend of invited competitions and RFQs. The authors take an in-depth look at past competitions won by young architects and planners, and survey the state of competitions through the world on a region by region basis. The end result is a compelling argument for an inclusive approach to conducting international design competitions.

Download Young Architects in Competitions for free at the following link:

https://crc.umontreal.ca/en/publications-libre-acces/

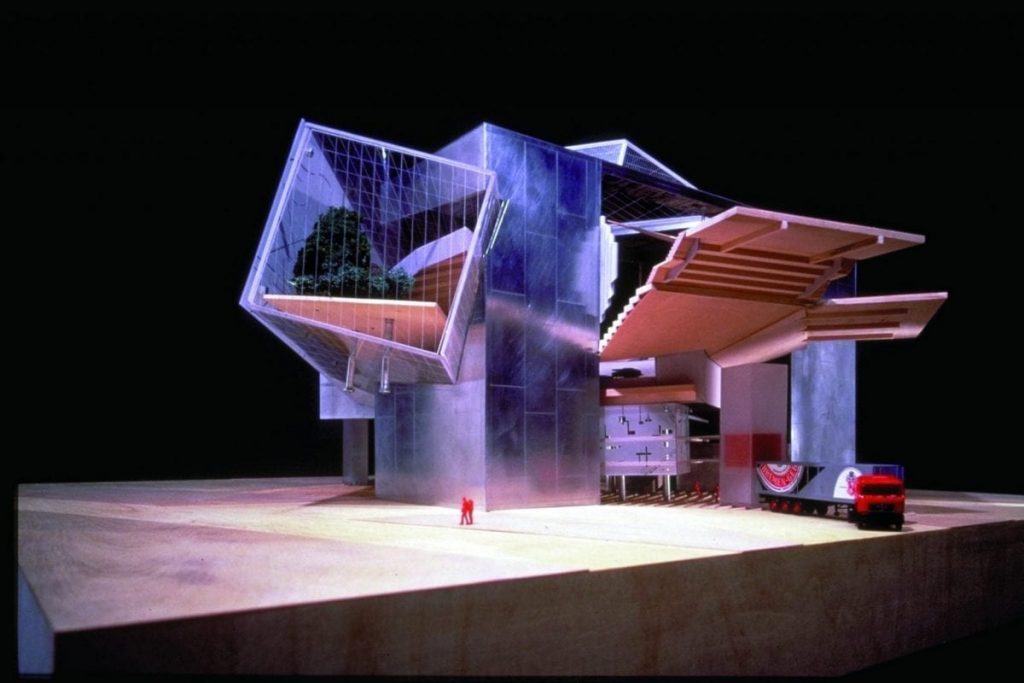

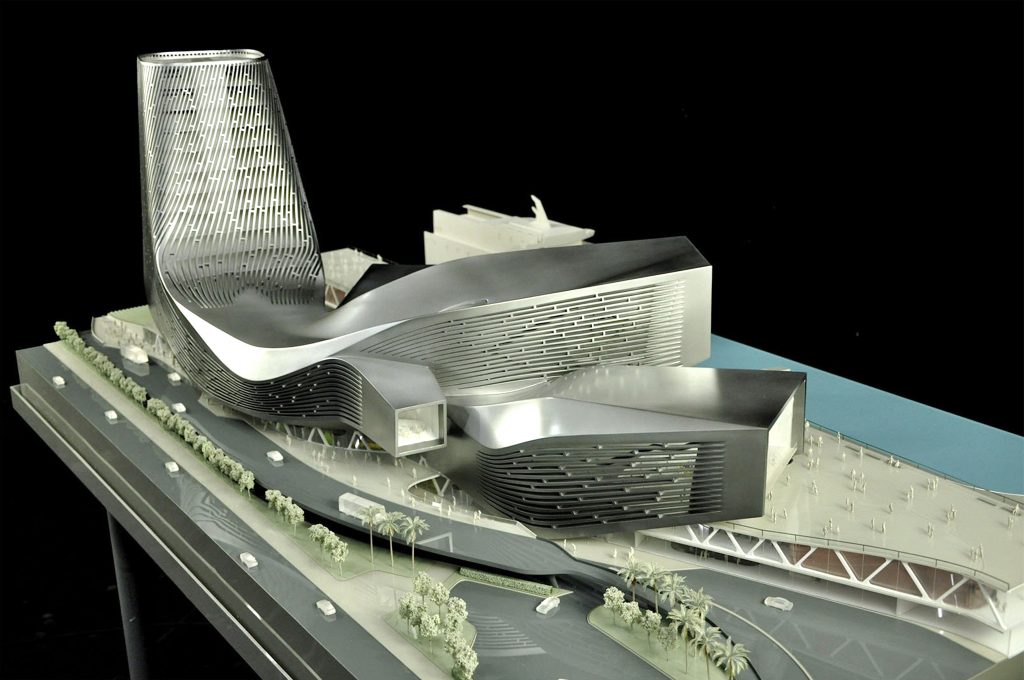

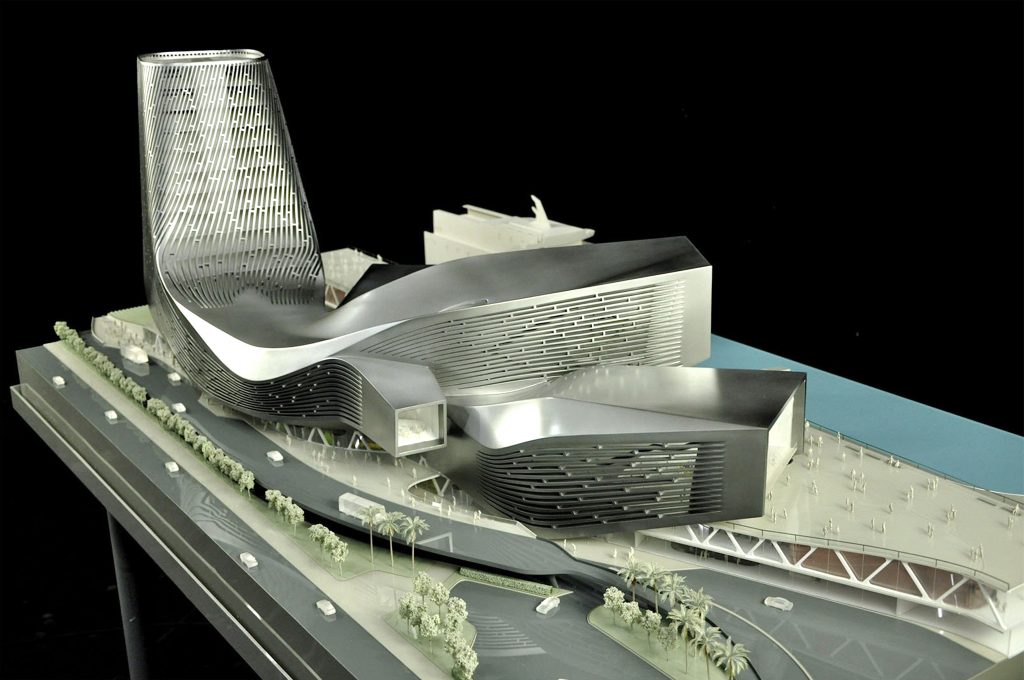

RUR model perspective – ©RUR

New Kaohsiung Port and Cruise Terminal, Taiwan (2011-2020)

Reiser+Umemoto RUR Architecture PC/ Jesse Reiser – U.S.A.

with

Fei & Cheng Associates/Philip T.C. Fei –R.O.C. (Tendener)

This was probably the last international open competition result that was built in Taiwan. A later competition for the Keelung Harbor Service Building Competition, won by Neil Denari of the U.S., the result of a shortlisting procedure, was not built. The fact that the project by RUR was eventually completed—the result of the RUR/Fei & Cheng’s winning entry there—certainly goes back to the collaborative role of those to firms in winning the 2008 Taipei Pop Music Center competition, a collaboration that should not be underestimated in setting the stage for this competition.

Read more…

Winning entry ©Herzog de Meuron

In visiting any museum, one might wonder what important works of art are out of view in storage, possibly not considered high profile enough to see the light of day? In Korea, an answer to this question is in the making.

It can come as no surprise that museums are running out of storage space. This is not just the case with long established “western” museums, but elsewhere throughout the world as well. In Seoul, South Korea, such an issue has been addressed by planning for a new kind of storage facility, the Seouipul Open Storage Museum. The new institution will house artworks and artifacts of three major museums in Seoul: the Seoul Museum of Modern Art, the Seoul Museum of History, and the Seoul Museum of Craft Art.

Read more…

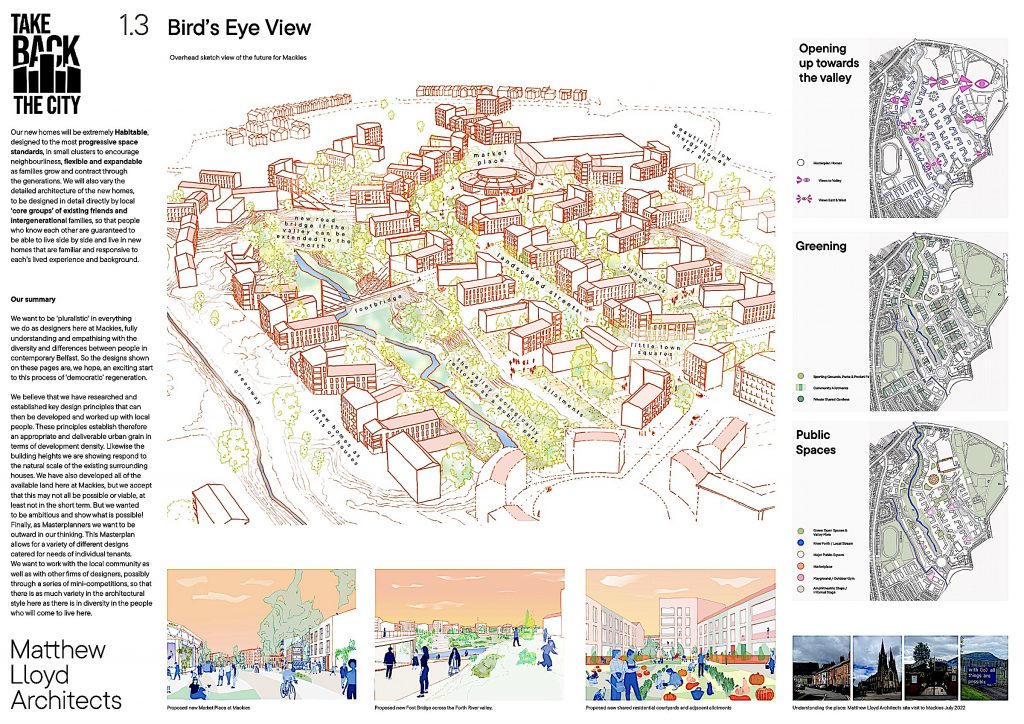

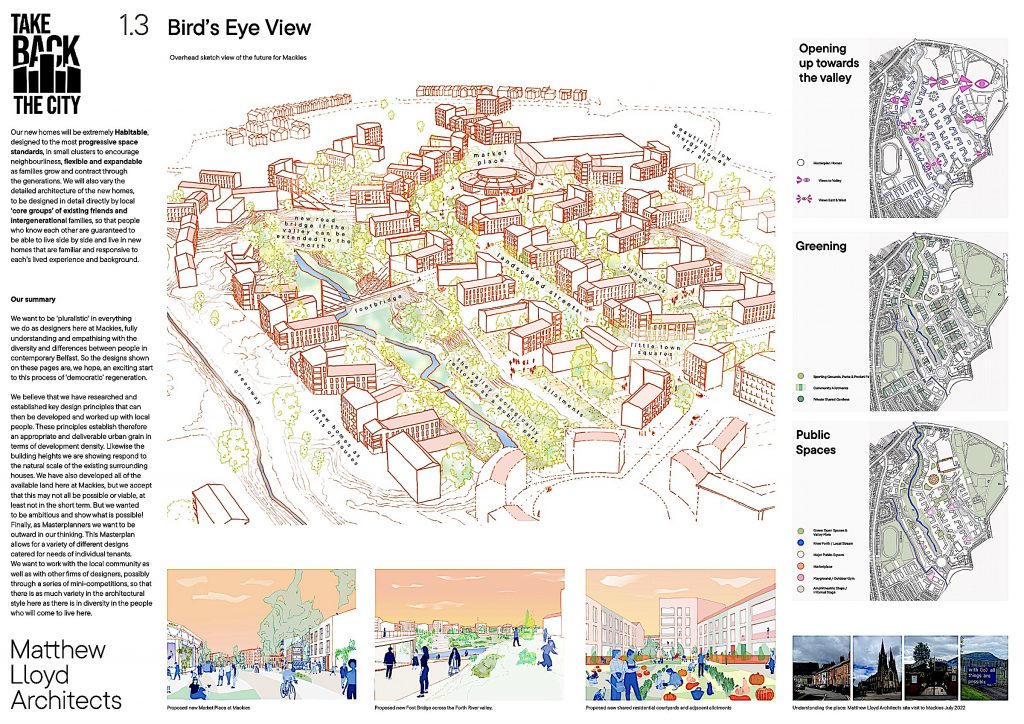

Belfast Looks Toward an Equitable and Sustainable Housing Model

Birdseye view of Mackie site ©Matthew Lloyd Architects

If one were to look for a theme that is common to most affordable housing models, public access has been based primarily on income, or to be more precise, the very lack of it. Here it is no different, with Belfast’s homeless problem posing a major concern. But the competition also hopes to address another of Belfast’s decades-long issues—its religious divide. There is an underlying assumption here that religion will play no part in a selection process. The competition’s local sponsor was “Take Back the City,” its membership consisting mainly of social advocates. In setting priorities for the housing model, the group interviewed potential future dwellers as well as stakeholders to determine the nature of this model. Among those actions taken was the “photo- mapping of available land in Belfast, which could be used to tackle the housing crisis. Since 2020, (the group) hosted seminars that brought together international experts and homeless people with the goal of finding solutions. Surveys and workshops involving local people, housing associations and council duty-bearers have explored the potential of the Mackie’s site.” This research was the basis for the competition launched in 2022.

Read more…

Alster Swimming Pool after restoration (2023)

Linking Two Competitions with Three Modernist Projects

Hardly a week goes by without the news of another architectural icon being threatened with demolition. A modernist swimming pool in Hamburg, Germany belonged in this category, even though the concrete shell roof had been placed under landmark status. When the possibility of being replaced by a high-rise building, it came to the notice of architects at von Gerkan Marg Partners (gmp), who in collaboration with schlaich bergermann partner (sbp), developed a feasibility study that became the basis for the decision to retain and refurbish the building.

Read more…

|