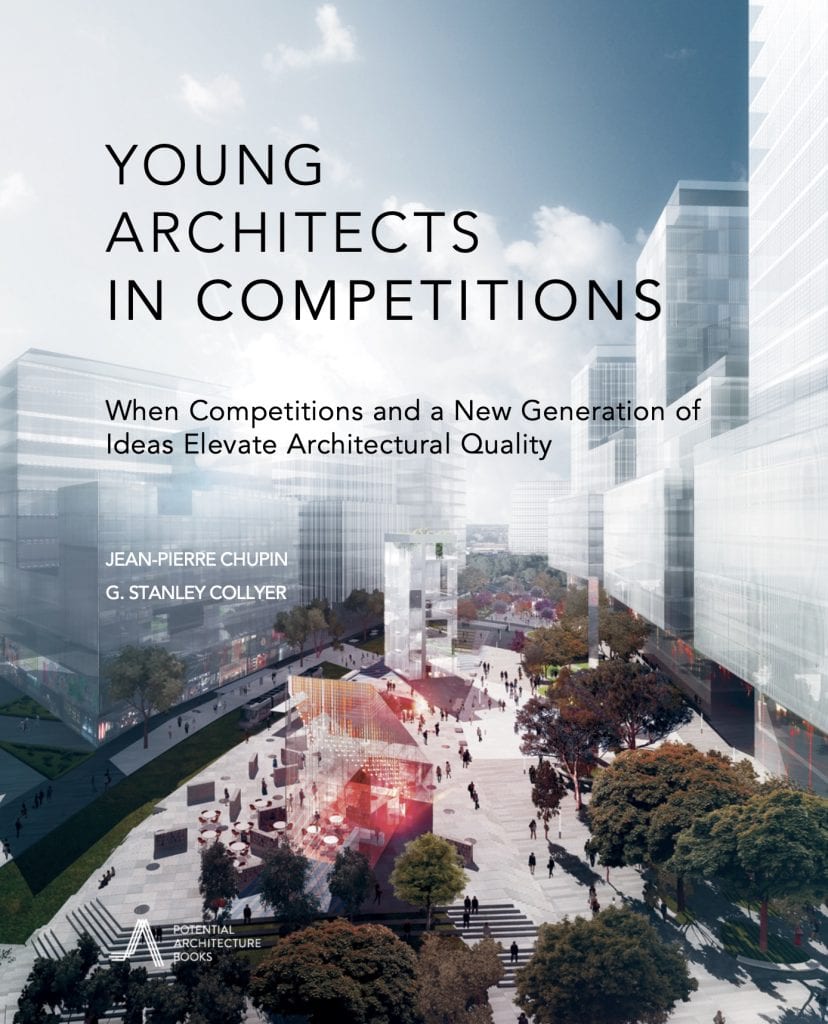

Remembrance on the Pacific Rim: The Canterbury Earthquake Memorial Dedication

Winning entry: Graga Vezjek Architect (Image © Simon Baker)

Living on the Pacific Rim can be a risky business. In L2010, Christchurch, New Zealand suffered a devastating series of earthquakes, resulting in the virtual destruction of half of the city’s urban fabric in the downtown area, the destruction of 100,000 homes, and the deaths of 185 of its inhabitants.

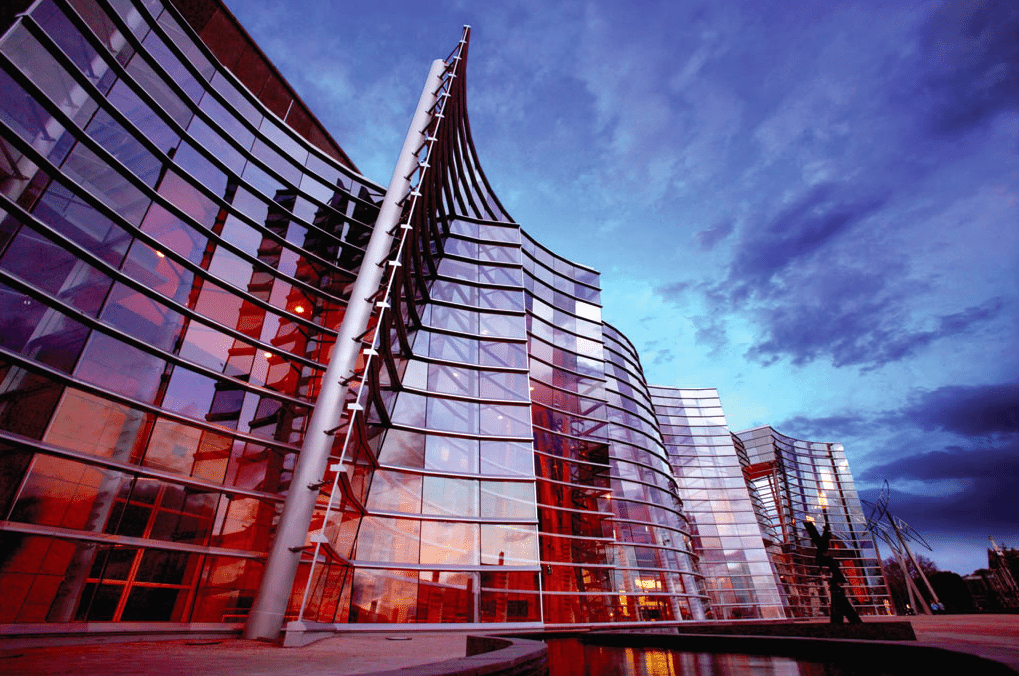

When we first heard of this disaster, one of our concerns was the survival of the new Christchurch Art Gallery, a stunning modern structure, which was the result of a 1998 design competition won by the Buchan Group of Sydney.* Based on the success of that competition, and its strong support by the local populace, using a similar process to select a design for a memorial to commemorate the victims of this disaster would have seemed to be a logical strategy.

Christchurch Art Gallery by Buchan Group (Sydney, Australia)

Competition (1998)

Completion (2003)

Science Island Design Competition

Image © SMAR Architecture Studio

Until the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1989, the occupied Baltic countries were known for their hi-tech contributions to the Soviet economy. As a carryover from that period, the Baltic nations still emphasize technology as a major factor in their economies. Thus, the establishment of a new Science museum by Lithuania in the nation’s capital of Kaunas is hardly surprising. To highlight the importance of this project, the government turned to a design competition, providing the museum with international exposure and attracting the attention of the global architectural community.

The stated purpose of the new project was clear from the competition brief:

‘Science Island’s mission is to popularize science through hands-on enquiry and exposition and celebrate recent achievements in science and global technologies. The Centre, within the celebrated university city of Kaunas, one of UNESCO’s global creative cities, will focus particularly on environmental themes and ecosystems, demonstrating sustainability and future energy technologies in the design of its own building. The circa 13,000 sqm site for the development is ideally positioned in close proximity to Kaunas’ historic Centras district, and most of Lithuania’s nearly three million residents live under an hour’s drive away.’

The Estonian National Museum Realized

A Former Soviet Airstrip in the Service of Estonian Cultural History

In 2005 the Estonian government decided to stage an international competition as a means of selecting a design for a new National Estonian Museum. Since there was already a Museum of Estonian History in Tallinn, the capital, one might assume that this was one factor in the decision to locate it in the second largest city, Tartu. One might ask, ‘why is this such a big deal, when we are only talking about a small country with a population of less than two million?’

Estonian National Museum Competition (2006)

View of completed project Photo: ©Takuji Shimmura Winning team: Lina Ghotmeh, Dan Dorell, Tsuyoshi Tane

Architecture in the service of the state can be a powerful tool. It lets a faceless bureaucracy present itself as a real thing. It can make ideals and memories into concrete facts. And it is usually big. A recent competition for a new National Museum in the small country of Estonia shows the potential and pitfalls of such a national architecture. While it can define the state, what does that mean when the state as a concept is a difficult idea these days? Now that true power lies not only with multinationals, but also with trans-national organizations like the European Union, of which Estonia has been a member since 2004, what is the state? Moreover, what history does a country that was only independent between 1925 and 1941, and then again since 1991, really have as such? What future can it imagine for itself? What is there left for architecture to represent?

The answer, if we can believe the results of the recent Estonian National Museum Competition, whose winner was announced this spring, is that architecture can use place above all else for meaning. This means not just utilizing the site in terms of its geography and geology, but also looking at, preserving and focusing on the full range of uses to which that site has been put, as well as the larger implications –both physically and conceptually—that a site might have. Everything human beings have done with a place, everything they have built there, and every association they have with a site as part of a much larger whole is the basic material the architect can use to design a construction that will bring out all of this history and all of these latent associations. The winning design in this competition, “Memory Field,” submitted by a multinational group of architects Dan Dorell and Lina Ghotmeh from Paris, and Tsuyoshi Tane from London, certainly accomplished this expression of place with a clear and simple proposal.

The site for the Estonian National Museum is not, as one might expect, in Estonia’s charming capital, Tallinn, but in the second largest city, Tartu. Located a few hours to the East of the seaside capital, almost on the border with Russia, Tartu is an industrial and trading node at the edge of the vast planes of pine forests and tundra that stretch from here to Siberia. It was on the outskirts of Tartu, in an 18th century manor house, that local agitators for defining a national identity by preserving local culture conceived the museum before there was even a country. In 1909 they began collecting “Finno-Ugric” (as the local population is called) artifacts and displaying them to show citizens that there were traditions of which they should be proud. Clothing, implements and especially lacework all showed the culture of a rapidly disappearing peasant population. Later, films documenting those peoples also joined the collections.

During the Second World War, the Museum moved to downtown Tartu, and it wasn’t until recently that the decision was made to reoccupy the former site. In the meantime, a large Russian airbase, now abandoned, took over much of the area, and its disused landing strip points directly at the site’s core, while the ruins of the military complex dwarf the remains of the former manor estate. A small lake provides a bucolic counterpoint to this rather bleak collection of artifacts. “This is the frozen edge of Europe,” says Winy Maas, who was part of the competition jury; “it is where you have a collection of incredible textiles dating back to the 14th century, but it will be housed on a site where wolves roam. You are really between worlds, and we thought the most important thing was to define that condition.”

Syracuse National Veterans Resource Center

An Interview with Dean Michael Speaks

Winning entry by ©SHoP Architects - View from Waverly Avenue

In this interview, juror Michael Speaks was clear that his remarks were that of an individual juror and that he in no way was speaking for the entire jury. In other words, this could not be considered as an official jury report.

COMPETITIONS: As for research possibilities, isn’t this new facility programmatically about reentry into civilian life by veterans?

Michael Speaks: Many veterans are non-traditional students, and having a prominent location and facility on campus for them is important. Indeed, one of the Veterans organizations to be housed in the National Veterans Resource Center (NVRC) is the Institute for Veterans and Military Families (IVMF). But, as you note, returning to a university campus that is welcoming is important, and the NVRC will serve as the central point of that re-entry.

You may know that Syracuse really grew to become a large university after the Second World War, based largely on veterans returning from the war and taking advantage of veteran’s benefits. There is a long history at Syracuse of involvement with the veterans’ community. When our new Chancellor, Kent Syverud, was hired, he made veterans' affairs and veterans' issues a central part of his administration and agenda. As I recall, during his first address as Chancellor, he emphasized veterans' issues as one of the most important issues to be addressed by his administration.

COMPETITIONS: From your experiences with competitions, you have experienced both open and invited competitions (Taiwan Taoyuan Terminal 3 competition). I wondered what was behind this choice for an invited competition process.

MS: Over the past 18 months we have been involved with developing a University Master Plan with Sasaki Associates. Early on the masterplan was designated a framework rather than plan, emphasizing that it would be a living document that would adapt and change over time. That plan was signed off on last May. Although it was never completely finished—it was called a ‘draft framework plan.’ The NVRC was is to be among the very first built projects to emerge from that framework plan. The decision was made to run the NVRC building selection as a competition, something the university had not done before. In the past, more typically there would have been a request for qualifications and sometimes a request for proposals, but never a competition as such. At least that is my understanding.

The idea for the two-stage competition was that the NVRC would be the first building project that resulted from the framework plan. It would be an important project in itself; but it would also announce the true start of the building process. The NVRC is necessarily located on one of the most prominent sites on the campus, and so there was great interest .in attracting world class design talent for the design of the building. As such, it would be a fitting project to celebrate the university’s history with veterans and the veterans community and to announce the commencement of the framework building process.

The: the university decided in consultation with the members of the campus framework advisory group and the Institute for Veterans and Military Families, to use the competition as the means of procuring a design firm to design the building. The decision was made to hire Martha Thorne, who is the Dean of the School of Architecture at the IE Madrid and Executive Director of the Pritzker Prize, as professional adviser.

COMPETITIONS: So my question is, why an invited competition, rather than an open competition, as was the case where you were a juror in Taiwan?

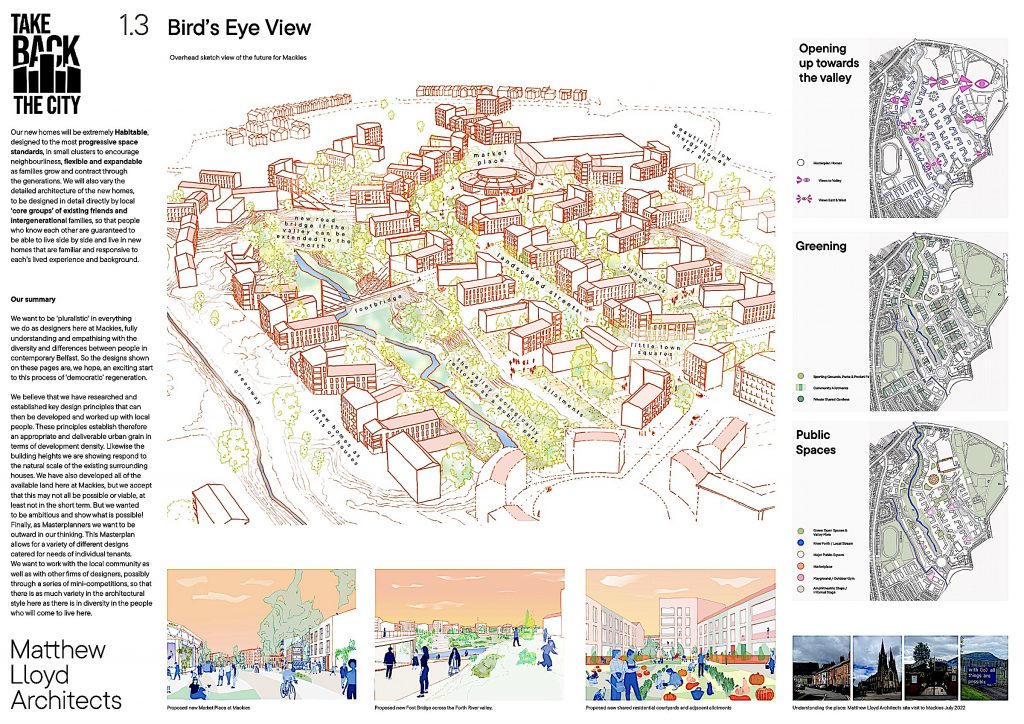

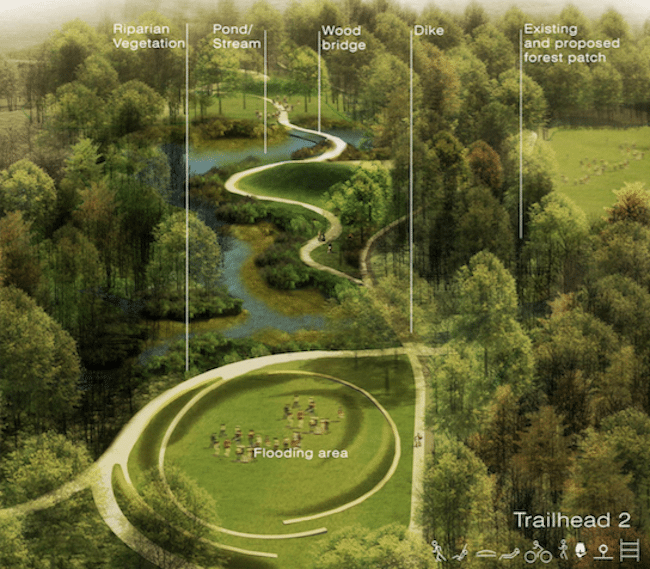

TWIN CREEKS: Trail as Experience Maker

First Place entry by Apliz Architecture (Images © Apliz)

Parks are becoming more than just a place for relaxation, hiking and recreation. They are becoming places to experience high design. One of the best examples, which has set the bar higher, is La Villette in Paris, where Barnard Tschumi designed a number of “follies” to enliven the park experience.

Now numerous examples abound here in the states, where landscape architects such as Michael Van Valkenburgh, Peter Walker, Chris Reed and George Hargreaves have added visual elements to their park designs. To give the Orange County Great Park an added feature, Ken Smith went so far as to feature a balloon ride to the former navy airstrip.

Kansas City saw a trail as an opportunity to add to the pedestrian biking and hiking experience. As part and parcel of a competition to enhance the visual and connective aspects of the trail, the organizers identified four “stations” along the way where the journey could take on additional meaning.

The illustrations and directions in the competition brief provided the competitors with a clear and exemplary framework for presenting creative solutions.

Map © Twin Creeks Design Competition

Finalists’ UK Holocaust Memorial Design Proposals

© Anish Kapoor and Zaha Hadid Architects & Malcolm Reading Consultants

After issuing a call for Expressions of Interest (EOI) in September, the United Kingdom Holocaust Memorial Foundation, together with competition adviser, Malcolm Reading Consultants, reduced a list of 97 applicants to ten finalists, all of which have submitted proposals for the design of the UK Holocaust Memorial.

The ten shortlisted firms are:

• Adjaye Associates and Ron Arad Architects (UK) with Gustafson Porter + Bowman, Plan A and DHA Designs

• Allied Works (US) with Robert Montgomery, The Olin Studio, Ralph Appelbaum Associates, Allied Info Works, Arup, Curl la Tourelle Head Architecture, PFB Construction ManagementServices Ltd, BuroHappold and Nathaniel Lichfield & Partners

• Anish Kapoor and Zaha Hadid Architects (UK) with Sophie Walker Studio, Arup Lighting, Event London, Lord Cultural Resources, Max Fordham, Michael Hadi Associates, Gardiner & Theobald, Whybrow, Access=Design and Goddard Consulting

• Caruso St John Architects (UK), Marcus Taylor and Rachel Whiteread with Vogt Landscape Architects, Arup Lighting and David Bonnett Associates

• Diamond Schmitt Architects (CA) with Ralph Appelbaum Associates, Martha Schwartz Partners and Arup

• Foster + Partners (UK) and Michal Rovner with Simon Schama, Avner Shalev, Local Projects, Samantha Heywood, David Bonnett Associates, Tillotson Design Associates and Whybrow

• heneghan peng architects (IE) with Gustafson Porter + Bowman, Event, Sven Anderson, Bartenbach, Arup, Bruce Mau Design, BuroHappold, Mamou-Mani, Turner & Townsend, PFB, Andrew Ingham & Associates and LMNB

• John McAslan+Partners (UK) and MASS Design Group with Lily Jencks Studio, Local Projects and Arup

• Lahdelma & Mahlamäki Architects (FI) and David Morley Architects with Ralph Appelbaum Associates, Hemgård Landscape Design, Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Dani Karavan and

• Studio Libeskind (US) and Haptic Architects with Martha Schwartz Partners, BuroHappold, Lord Cultural Resources, Alan Baxter, Garbers & James and James E. Young

Although the Jury will make a final decision in the selection process, the public is invited to offer their feedback and specify which design team they are referring to: ukhmf@cabinetoffice.gov.uk.

M20 – Museum of 20th Century Extension Competition

This is not what we fought for!

by Wilfried Wang*

Winning design: ©Herzog & de Meuron

Wilfried Wang’s commentary on the competition results for the extension of Mies’s Museum of the 20th Century (M20) was published in the German journal, Bauwelt (40.2016). The author is the founder of the Berlin architectural practice Hoidn Wang Partner with Barbara Hoidn and has been the O’Neil Ford Centennial Professor in Architecture at the University of Texas at Austin since 2002. The text, translated by the Editor, is a slightly modified version (by the author) that appeared in Bauwelt.

Both in architectural and urbanistic terms, the jury’s misguided selection of the Herzog de Meuron entry as the winner of the M20 competition is another missed opportunity for Berlin.

By extending the form of this introverted structure to cover the entire competition site, little or no value is added to the immediate environs. To the contrary, that and the immense surfaces of the facades, right up to the edge of the pedestrian walkways, only serve to diminish the importance of the surrounding buildings. All the trees to the south of the site will disappear, and 90% of the outer walls of the building, regardless of the suggested use of porous brick detailing, are completely closed off. Only the eastern entrance of the Herzog de Meuron plan faces the main entrance of Scharoun’s State Library; the other two main entrances lack any such connection with the urban context. Thus, the Cultural Forum gains nothing in urban quality, but rather the sense of desolation will increase.

The corridors stacked over one another, labeled “Boulevards” by the architects, are connected in the quadrants by smaller corridors and stairs. The metaphor, “Boulevard,” is as misleading as was Le Corbusier’s “rue intérieur.” Boulevards are accessible 24 hours a day as open public spaces. In the evenings these corridors will be closed to the public.

Rectangular exhibit areas are placed on three levels—not easily accessible to the visitor as a result of the labyrinth-like circulation plan. What is so innovative about this? The Goetz Pavilion was innovative.

Viewed from an artistic- and architecture-historic point of view, the selection of this design was an egregious mistake. First of all, a gable roof design is not appropriate for this Cultural Forum, and, secondly, it does not express the modern spirit; actually it is quite the opposite. Originally, the Cultural Forum was not only West Berlin’s gesture to the East, but also an attempt to replace the Nazi north-south axis with a modern alternative.

The lack of sensitivity, unnecessary haste followed by yearlong inaction and a desire for label-architecture have strangely culminated in a provincial selection. The shortlisted designs from the initial open competition were more modern, sensitive, and led one to assume that a different solution would be in store.

If this design were actually to be built, this unfortunate selection process would result in a catastrophe. This reminds me of the competition for the City of Culture for Santiago de Compostela. In that instance I was the sole juror to vote against the Eisenman scheme. Then my arguments fell on deaf ears. I was not a juror in the M20 competition. For this reason, I’m thankful that I can air my concerns about this result; however, I believe that my concerns will once again suffer the same fate. -WW

*The following should be pointed out: For his Master's degree in 1981, the author researched six cultural centers—amongst others, London's South Bank Centre, Paris' Centre Beaubourg and Berlin's Kulturforum. In 1992 the author published a monograph on the work of HdM. The author was a member of the jury for the limited competition for the extension of the Basel Kunstmuseum, which was unanimously awarded to Gigon & Guyer; HdM was one of the five invited architects. In 2013 the author published a monograph on Scharoun's Philharmonie, therein his essay on "The Lightness of Democracy." As part of his activities in the Architecture Section of the Akademie der Künste in Berlin, the author was co-organizer of a number of public discussions on the development of the Kulturforum, in which politicians and representatives of the Prussian Cultural Foundation (the users of M20) participated. In 2014 and 2015 the author set the design of M20 as a test for advanced design studios. Finally, the competition entry for the first phase of the M20 selection process by the author's office was eliminated in the first round: www.hoidnwang.de/04projekte_53_de.html.

View of site from Mies van der Rohe's Museum of the 20th Century to Hans Sharoun's Berlin Philharmonic

Photo: Stanley Collyer

The above photo of the M20 site makes abundantly clear the difficult challenges facing the architects who tried to produce an acceptable solution for the extension of the Mies museum. One might normally assume that a grand plaza would have been an appropriate answer. However, an extension of the M20 came into the conversation when a major art collector offered the collection to the museum in its enirety—necessitating more exhibit space.So the solution to this expansion had to lie in a design competition.

First of all, the very presence of two easily recognized architectural icons facing each other across the site would normally be enough to intimidate anyone. So the initial question in the back of everyone's mind would have been: should this addition simply constitute a link between the two buildings; or should it be something more?

Organized in two stages, the first, anonymous stage was open internationally and resulted in eight finalist entries advancing to a second stage (http://competitions.org/2016/02/berlins-20th-century-art-museum-competition/?preview_id=18468&preview_nonce=20af7e537d&_thumbnail_id=-1&preview=true). From the 480 competition entries, one would have assumed that at least one entry would have been convincing enough to gain favor not only from the jury, but also the community. The addition of this second stage was to accommodate short-listed name firms, so there could be no complaints that high-profile, established architects were not part of the mix. Based on the final rankings from the second stage, none of the premiated designs really solved this challenge satisfactorily. Most tried to recognize the importance of a sightline between the two icons by going at least partially underground.

The two firms that took this most to heart were both from Japan—SANAA and, no surprise, Sou Fujimoto, with the latter covering the entire partially submerged structure with vegetation. The second-place winner from Denmark found favor from the main client with what looked to be very commercially looking solution, what one might imagine as an outdoor shopping center. The most extreme anti-urbanistic example honored by the jury with a merit award was OMA's pyramid-like scheme, completely blocking any relationship between Mies and Sharoun by inserting their own icon in between the two.

When Herzog & de Meuron's design was declared the winner, it had to come as somewhat of a surprise. Structurally no more than a shed in appearance, it seemed to be completely out of character with all of its neighbors—almost thumbing its nose at them. The abundant use of brick, its blank facade facing the street, and the claim by the authors that the corridor cut through the middle as a "boulevard" would serve as a symbolic link between the Museum and Philharmonie, was hardly convincing. This is especially true when one realizes that it would be closed off evenings to all comers. As an urbanistic solution and example of architectural expression, the winner unfortunately fell flat on its face. -Ed

A Symbol of Gratitude: The Tri An Monument Competition

For residents of Louisville, Kentucky, it would come as no surprise that the city’s Vietnamese community would support a competition commemorating the friendship and support of the Americans both in Vietnam and the U.S. and our welcome for the Vietnamese people who have arrived in this country. The foundation established to realize this concept was named “Tri An,” which means “deep gratitude.” According to the competition brief, “It is important to recognize the numerous humanitarian efforts and good deeds done by the U.S. military and the many Americans who went far beyond the call of duty to help the South Vietnamese people.

As is the case with many non-government supported projects, this one also had a patron who lent his support to project, Yung Nguyen, the local founder and patron of the Tri Ân foundation, also the founder of a high-tech firm. To administer the competition, the foundation engaged the services of a local architecture firm, Bravura, which had a notable track record in memorial competitions, having previously acted as professional adviser for the acclaimed Patriots Peace Memorial competition in Louisville.

In setting the bar for the anticipated winner, the competition brief stated that the design:

- Be unique;

- Be dramatic, timeless, and contemplative;

- Have many levels of meaning;

- Have the seductive power to invite a closer look, even to the casual observer;

- Be in harmony with the landscape, and be compatible with the other features and uses of the park in which it will reside;

- Be a creative use of the hillside site; incorporating its views, topography, and natural wooded backdrop;

- Successfully convey the Overriding Purpose and Interpretive Themes stated in these Guidelines.

To attract the widest possible audience, the organizers decided on an international, open and anonymous, two-stage competition as the best model. It was decided to award three finalists the opportunity to have their designs equally reviewed for the possible realization of the project in a second phase. For their efforts, each was to receive compensation of US $4,000.

Not Just a Coming Attraction: ZNE is Already Here!

Professional Merit Award winner - "Nexus" by Dialog (Vancouver, Canada)

Several years ago, Zero Net Energy, or ZNE as it is often referred to, would have been an unthinkable goal for any community in this country, let alone for an entire state. But in California, it is certain to become a household word by the end of this decade. The City of Santa Monica recently passed an ordinance requiring all newly built single-family homes, duplexes, as well as multi-family structures, to be in compliance with ZNE codes. By the year 2020, the State of California will require the implementation of a similar step in housing construction. According to California’s Green Building Code, a ZNE home is one that produces as much renewable energy on-site as it consumes annually.

Contrary to anti-sustainability positions taken by some government officials in other states—most notably in Florida—California has been at the forefront in promoting energy efficiency measures. As an offshoot of this trend, a series of competitions supported not only by the AIA California, but also by the primary energy provider in the state, PG&E have taken place annually since 2011—all at different sites. Although conceived as ideas competitions, the clients who were considering construction projects participated in supplying the necessary site and volume data for the program, and it was probably understood that some of the ideas from the competitions would be incorporated in the ultimate projects.

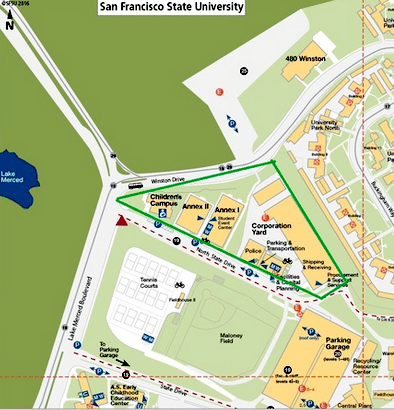

In this year’s 2016 Architecture at Zero competition, the site was located at San Francisco State University, near Lake Merced in the southwestern area of the city. As a potential client, the university supplied data for a student residence project, especially important to the San Francisco area because of the high cost of housing. One negative outcome of this scenario has been a low student retention rate. By targeting affordable housing for students, the university sees this as part of the solution.

Competitors were tasked to regard the design challenge with these priorities in mind:

“By encouraging innovative design solutions to site-specific design challenges, the competition aims to broaden thinking about the technical and aesthetic possibilities of zero net energy projects. Further, it seeks to raise the profile of ZNE among built-environment professionals, students, and the general public in California and beyond.”