The Estonian National Museum Realized A Former Soviet Airstrip in the Service of Estonian Cultural History

In 2005 the Estonian government decided to stage an international competition as a means of selecting a design for a new National Estonian Museum. Since there was already a Museum of Estonian History in Tallinn, the capital, one might assume that this was one factor in the decision to locate it in the second largest city, Tartu. One might ask, ‘why is this such a big deal, when we are only talking about a small country with a population of less than two million?’

Since this museum’s emphasis is heavily weighted toward illustrating the country’s finno-ugric origins, both in language and tribally, Estonia’s Russian neighbor could hardly interpret this as a friendly gesture—considering over forty percent of Estonia’s population is currently Russian. It wasn’t always that way. Russian influence and the migration of Russian speakers to Finland coincided with the end of World War II and the Cold War. Estonia’s attraction to Russians during that era was not only linked to the region as a hightech center; with that came a slightly higher living standard. When the breakup of the Soviet Union and the simultaneous recreation of independent Baltic States occurred in 1989, the Estonian majority took power, and concurrently, made Estonian the official language of the country. If this wasn’t enough, its cultural positioning to Finland and the West has intensified with its membership in the EU and NATO. Since then, a delicate balance has been struck between the two cultures; but the rise of Russian nationalism under Putin could spell trouble internally for the country. Nationalism is okay for Moscow, but dangerous when occurring in a neighboring country—especially when it is a former Soviet Republic.

The Site The site of the new museum, an abandoned Soviet military airstrip outside of Tartu, also has symbolic meaning. That the winning design used the airstrip to draw attention to the departure of the Russians could hardly sit well with their neighbor to the east. It was a strong statement of Estonian identity with cultural ties to the west dating back centuries as members of the Hanseatic League. As Aaron Betsky noted in his article for the Fall Issue of COMPETITIONS magazine in 2007, commenting on the role of “architecture as a powerful tool in the service of the state…architecture can use place above all else for meaning.” (For the full article and all of the premiated entries, http://competitions.org/2017/04/estonian-national-museum-competition-2006/) In this competition, the winners, DGT (Paris/London), fully understood the site, its implications, and the challenges it presented. At first glance, their visually simple solution could be interpreted as less about architectural symbolism, than providing a flexible, sleek container as a solution to the program. But by integrating the structure so symbolically with the runway, the message could only be: That element of history is behind us forever and has been supplanted by a connection to our finno-ugric past, building on that for a better future—as represented by a modern structure.

Photo: ©Drone @Tiit Sild

As reported in Betsky’s article, DGT’s design was pretty controversial; not only was it a split decision by the jury, Dutch juror Winy Maas (MVDRV) had to return to Estonia later to offer support for the jury’s choice. In the end, the DGT design was implemented, and finally dedicated last year. From our vantage point, this project, though located in what some might consider a ‘no-mans-land,’ will certainly stand as one of the most remarkable museum projects of the early 21st Century.

Unless otherwise noted, all photos: ©Takuji Shimmura

More recently, two of the team members from that competition have established their own firms: • Lina Ghotmeh at: Lina Ghotmeh — Architecture (www.linaghotmeh.com)

• Tsuyoshi Tane at: Atelier Tsuyoshi Tane Architects (www.at-ta.fr) |

1st Place: Zaha Hadid Architects – night view from river – Render by Negativ

Arriving to board a ferry boat or cruise ship used to be a rather mundane experience. If you had luggage, you might be able to drop it off upon boarding, assuming that the boarding operation was sophisticated enough. In any case, the arrival experience was nothing to look forward to. I recall boarding the SS United States for a trip to Europe in the late 1950s. Arriving at the pier in New York, the only thought any traveler had was to board that ocean liner as soon as possible, find one’s cabin, and start exploring. If you were in New York City and arriving early, a nearby restaurant or cafe would be your best bet while passing time before boarding. Read more… Young Architects in Competitions When Competitions and a New Generation of Ideas Elevate Architectural Quality

by Jean-Pierre Chupin and G. Stanley Collyer

published by Potential Architecture Books, Montreal, Canada 2020

271 illustrations in color and black & white

Available in PDF and eBook formats

ISBN 9781988962047

Wwhat do the Vietnam Memorial, the St. Louis Arch, and the Sydney Opera House have in common? These world renowned landmarks were all designed by architects under the age of 40, and in each case they were selected through open competitions. At their best, design competitions can provide a singular opportunity for young and unknown architects to make their mark on the built environment and launch productive, fruitful careers. But what happens when design competitions are engineered to favor the established and experienced practitioners from the very outset? This comprehensive new book written by Jean-Pierre Chupin (Canadian Competitions Catalogue) and Stanley Collyer (COMPETITIONS) highlights for the crucial role competitions have played in fostering the careers of young architects, and makes an argument against the trend of invited competitions and RFQs. The authors take an in-depth look at past competitions won by young architects and planners, and survey the state of competitions through the world on a region by region basis. The end result is a compelling argument for an inclusive approach to conducting international design competitions. Download Young Architects in Competitions for free at the following link: https://crc.umontreal.ca/en/publications-libre-acces/

Helsinki Central Library, by ALA Architects (2012-2018)

The world has experienced a limited number of open competitions over the past three decades, but even with diminishing numbers, some stand out among projects in their categories that can’t be ignored for the high quality and degree of creativity they revealed. Included among those are several invited competitions that were extraordinary in their efforts to explore new avenues of institutional and museum design. Some might ask why the Vietnam Memorial is not mentioned here. Only included in our list are competitions that were covered by us, beginning in 1990 with COMPETITIONS magazine to the present day. As for what category a project under construction (Science Island), might belong to or fundraising still in progress (San Jose’s Urban Confluence or the Cold War Memorial competition, Wisconsin), we would classify the former as “built” and wait and see what happens with the latter—keeping our fingers crossed for a positive outcome. Read More…

2023 Teaching and Innovation Farm Lab Graduate Student Honor Award by USC (aerial view)

Architecture at Zero competitions, which focus on the theme, Design Competition for Decarbonization, Equity and Resilience in California, have been supported by numerous California utilities such as Southern California Edison, PG&E, SoCAl Gas, etc., who have recognized the need for better climate solutions in that state as well as globally. Until recently, most of these competitions were based on an ideas only format, with few expectations that any of the winning designs would actually be realized. The anticipated realization of the 2022 and 2023 competitions suggests that some clients are taking these ideas seriously enough to go ahead with realization. Read more…

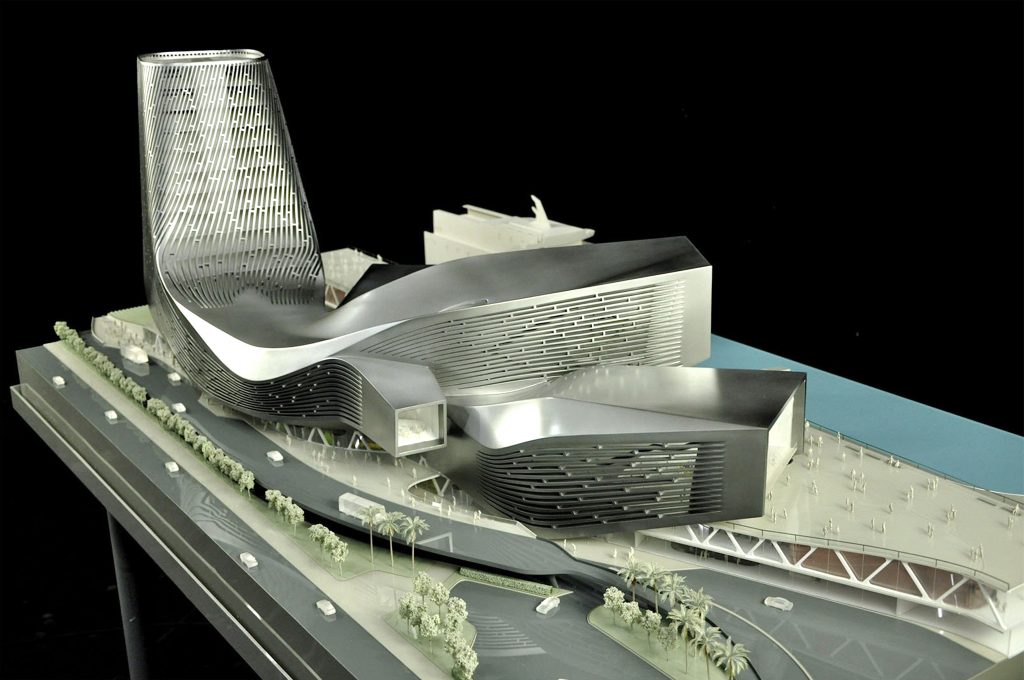

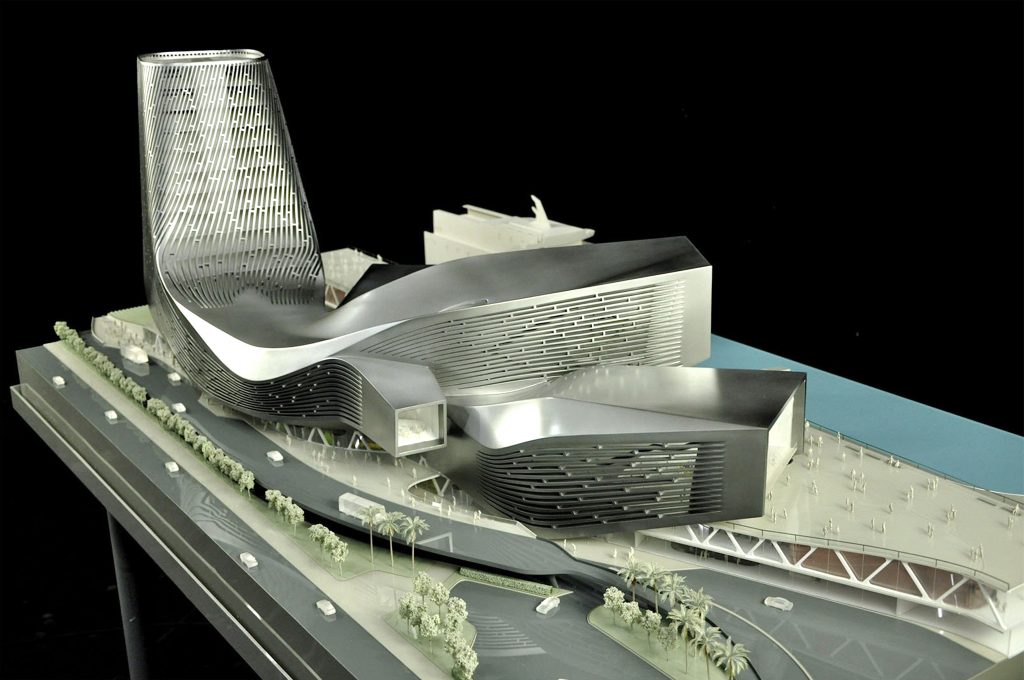

RUR model perspective – ©RUR

New Kaohsiung Port and Cruise Terminal, Taiwan (2011-2020)

Reiser+Umemoto RUR Architecture PC/ Jesse Reiser – U.S.A.

with

Fei & Cheng Associates/Philip T.C. Fei – R.O.C. (Tendener)

This was probably the last international open competition result that was built in Taiwan. A later competition for the Keelung Harbor Service Building Competition, won by Neil Denari of the U.S., the result of a shortlisting procedure, was not built. The fact that the project by RUR was eventually completed—the result of the RUR/Fei & Cheng’s winning entry there—certainly goes back to the collaborative role of those to firms in winning the 2008 Taipei Pop Music Center competition, a collaboration that should not be underestimated in setting the stage for this competition Read more…

Winning entry ©Herzog de Meuron

In visiting any museum, one might wonder what important works of art are out of view in storage, possibly not considered high profile enough to see the light of day? In Korea, an answer to this question is in the making. It can come as no surprise that museums are running out of storage space. This is not just the case with long established “western” museums, but elsewhere throughout the world as well. In Seoul, South Korea, such an issue has been addressed by planning for a new kind of storage facility, the Seouipul Open Storage Museum. The new institution will house artworks and artifacts of three major museums in Seoul: the Seoul Museum of Modern Art, the Seoul Museum of History, and the Seoul Museum of Craft Art.

Read more… |