The Urban Confluence Silicon Valley Competition

Urban Confluence Silicon Valley winner: ©SMAR Architecture Studio

After several stops and starts over an extended period of time, the winner of the Urban Confluence Design Competition was named in early March, 2021. SMAR Architecture Studio’s The Breeze of Innovation, which prevailed over two other shortlisted finalists from the original 963 entries, won with a novel tower-like structure consisting primarily of hundreds of rods, generating energy while swaying in the wind.

Urban Confluence Silicon Valley winner: ©SMAR Architecture Studio

Project Origins

In 2017, three founders of a local non-profit established The San Jose Light Tower Corporation (SJLTC). The founders of the non-profit, Restaurateur Steve Borkenhagen, construction company executive, Jon Ball and filmmaker Thomas Wohlmut, saw its primary mission in designing and building a new tower as a San Jose and Silicon Valley landmark. This idea was based on the memory of the original San Jose Electric Light Tower (1881-1915), a 22-story structure, located in downtown San Jose, which came down as the victim of a gale, never to be rebuilt.

Realizing such a project depends on public support, the SJLTC cleared the first hurdle toward building a public consensus with the unanimous endorsement of the San Jose City Council—for the organization to move forward “with plans to design and construct an artistically-inspired and iconic structure in downtown San Jose.”

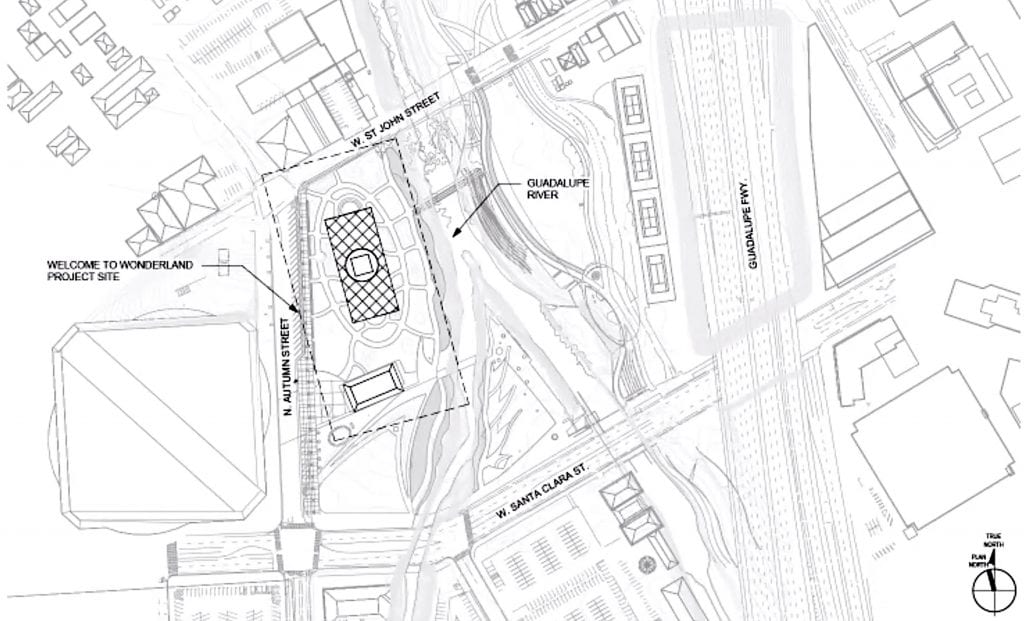

To realize such an idea, the project required a site, funding, and a design. Arena Green in Guadalupe River Park was thought to be the ideal location for the project. At the confluence of two rivers and in proximity to downtown San Jose, this was an easy choice.

As for the design, they understood that a competition not only would be the natural road to arrive at a suitable design for such an ambitious project, but generate a maximum amount of publicity on the way to seeing the project built. One change occurred along the way: After some input from various parties, it was determined that placing sole emphasis on the tower as the design solution was too narrow as a concept, and that a more flexible challenge would generate more interest. Thus the project took on the name of the site at the confluence of the two rivers, Urban Confluence Silicon Valley Competition.

The competition was launched in the summer of 2019, and the entries were to be juried after a submission deadline of October 15, 2019. This deadline was ultimately extended, as a surge of comments apparently led to some modifications in the brief. Moreover, the ugly appearance of Covid-19 resulted in using Zoom for most of the meetings, most importantly for the later jury sessions. The final deadline was set for July 1, 2020, and the response was the receipt of 963 entries! The program stated that three finalists would be shortlisted and each would receive $150,000 to fine-tune their designs before the final presentations were to occur and a final decision had been reached.

The delay by eight-plus months in the scheduled document submissions apparently had to do with some shortcomings in the competition brief at that time—aside from deemphasizing the tower. Based on our conversations with a competition participant, some essential items such as a site section were missing from the document; and the project managers indicated that questions from numerous potential participants had necessitated the rescheduling. All this suggested that the sponsors were dealing with a rather significant learning curve on the way to their ultimate goal. In the end, it would appear that the final adjustments to the competition brief bore fruit; for the quality of the entries is certainly a testament to the efforts of the sponsors.

Since funding for the project had not yet been established, the client undertook a very sophisticated PR campaign, with various online presentations, partially serving as vehicles for fundraising. With several Forbes 500 firms located in Silicon Valley, some might assume that the funding of such a project might not pose much of a problem. But the sponsors were obviously not taking any chances with the budget still an unknown, and was well advised not to do so.

Choosing a Design

A Community Competition Panel, comprised of 34 local community leaders including artists, architects, environmentalists, and business leaders, convened for two days of deliberation sessions on July 18 and 19. They evaluated all 963 qualified submissions as a group and concluded their work by recommending 47 submissions to the jury for consideration. Those 47 entries are viewable on the competition website. When the jury of 14 convened for deliberations on August 3, 4, and 8. They reviewed and evaluated all 963 qualified submissions and selected the competition’s 3 finalists. Here it is of note to discover that none of the Community Panel’s selections were included among the finalists.

The three finalists were:

• Fer Jerez and Belen P. de Juan, SMAR Architecture Studio, Perth, Australia

• Rish Ryusuke Saito, Sci-Arc/RNT Architects, San Diego, CA

• Qinrong Lui / Ruize Li, Harvard GSD, Cambridge, MA / Singapore

With eight design professionals and six stakeholders named to the jury, the quality of this panel was beyond reproach. They were:

• Jon Ball, Chair of the Board of Directors, SJLTC, San Jose, CA

• Susan Chin, FAIA, Principal, DesignConnects, New York, NY

• Jon Cicirrelli, Director, City of San Jose Department of Parks, Recreation & Neighborhood Services, San Jose

• Julia Czerniak, Associate Dean and Professor of Architecture, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY

• Jerry van Eyck, Landscape Architect/Industrial Designer, New York

• Walter Hood, Hood Design Studio, Oakland, CA

• Katja Irvin, Sierra Club Loma Prieta Chapter, Palo Alto, CA

• Lisa Iwamoto, Architect/Structural Engineer, San Francisco, CA

• Daan Roosegaarde, Studio Roosegaarde, Rotterdam

• Erin Salazar, Artist, Director, Exhibition District San Jose, CA

• Jodi Starbird, President, Board of Directors, Guadalupe River Park Conservancy

* Rob Steinberg, FAIA, Steinberg Hart, Los Angeles, CA

• John Travis, Adobe Marketing, San Francisco, CA

• Michael E. Willis, FAIA, NOMA, New York, NY

Jury Feedback

By posting all of the entries, especially those 47 that survived the first round, visitors to the site could see the large variety of strategic approaches to the design challenge, documenting the client’s decision to change the narrow scope of the competition from tower to a more expansive focus on the site. Moreover, it also revealed the high quality of the entries. By visiting the competition website, one could also understand the difficulty the jury would have encountered in raising one design above all of the rest for final consideration by the client. By posting a selected number of entries for public viewing, the sponsors exhibited a transparency that often is absent from most competitions in the U.S. Moreover, the high number of entries can undoubtedly be attributed to the fact that no entry fee was required—usually the case in many ideas competitions. Added to that was the stated intent to award $150,000 to each finalist to fine-tune their designs.

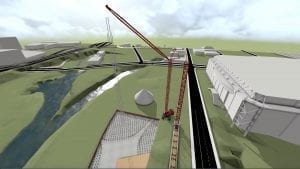

An open interview process of the jurors with the designers, often supported by their various team members—engineers, lighting, etc.—was included in the jury process. Here, concerns voiced by the jurors concerning circulation, materials and buildability were discussed in some detail. To nobody’s surprise, the discussion with SMAR Studio’s winning team concentrated on buildability issues, i.e., the rods ability to deal with high winds, earthquakes, etc. Only in the case of the ramping, allowing visitors access to the top of the “tower,” were some issues raised that probably will have to be addressed in development.

The Second Phase Designs

During the second phase of any competition, we always look to determine what changes might have taken place to improve the chances of each finalist. In the case of this competition, the final presentations of two of the teams revealed some major changes had taken place in their initial schemes, whereas the design presented by the eventual winner, SMAR Architecture Studio looked very much like phase one, and, aside from some additional renderings, focused primarily on a more detailed description of the construction process. Here we have no idea whether or not the jury issued any instructions to the teams in the interim as to what improvements they might address.

Whereas the SMAR team had several years of experience contending in several competitions, including winning a major competition organized in two stages, the other two finalists were recent students and needed to add a significant number of tested partners to establish legitimacy—that they could actually realize this project. For that they needed established firms in both architecture and engineering as partners. In the case of the Welcome to Wonderland team headed by Rish Ryusuke Saito, the most important additions were Huitt-Zollars, Inc. (architecture) and Walter P. Moore, PE (Engineering). In the case of Qinrong Lui and Ruize Li from Harvard, HKS (architecture) and Martin + Martin (engineering) were necessary to the success of their venture.

Going forward, the SJLTC’s organization of a formidable PR campaign to support the funding of the competition has led to a successful result. Its staging of numerous community meetings has been used as a vehicle both to garner regional support for the project, as well as serve as a fundraising tool. It was successful in funding the competition itself, having raised over $2M; now comes the hard part—coming up with a budget and realizing the project. Assuming the project goes on to completion, the three leaders that came up with the idea remind us of those two non-architects who were instrumental in initiating the High Line project in New York: good ideas by inspired citizens can have very positive effects on the future of their urban environments.

Winning Entry

Breeze of Innovation

SMAR Architecture Studio

Fernando Jerez / Belen P. de Juan (co-designers), Perth, Australia

MBH Architects, (architecture), Alamada, California

Magnusson Klemencic Associates (Engineers), Seattle, Washington

Key Anderson, Niteo (lighting), San Francisco/Seattle/Singapore

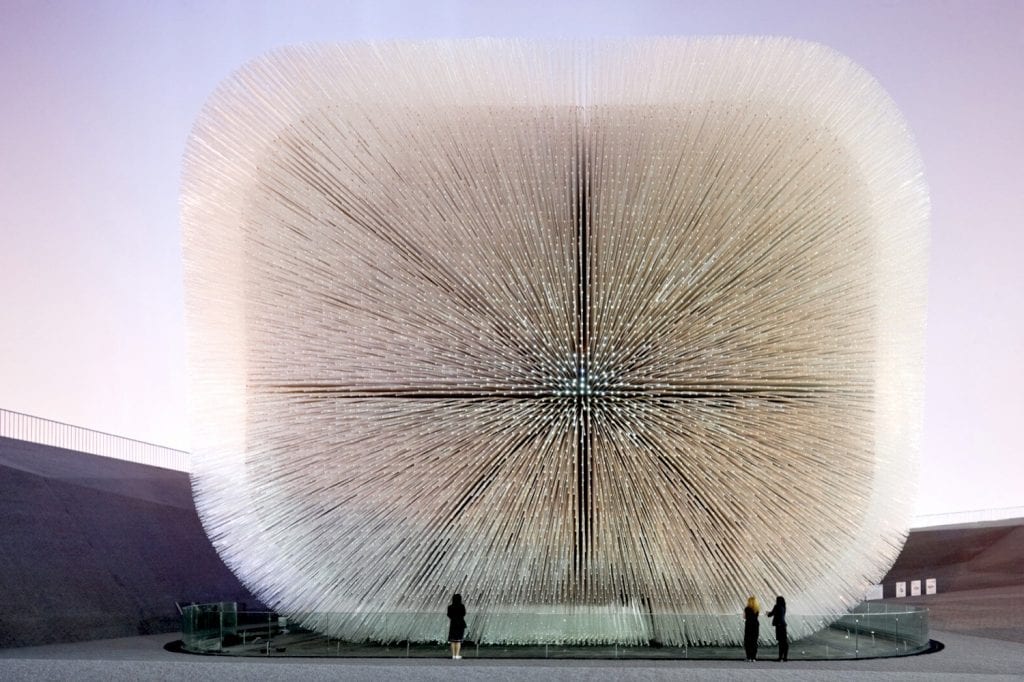

Was SMAR’s kinetic structure a complete outlier when looking at materials, their use, and actual projects that had taken place in recent history? Previous designs and actual structures along the way had pointed in that direction (see below). In 2007, Thomas Heatherwick’s Seed Cathedral competition-winning design for U.K.’s pavilion in the Shanghai 2010 Expo, eventually was honored with the Expo’s award for best pavilion by a large margin. In 2011, Sou Fujimoto of Japan won the Taiwan Tower competition with a structure almost completely consisting of rods. Other tower competitions, especially in Taiwan and China, had also produced results testing the structural imagination.

Heatherwick Studio’s Seed Cathedral, 2010 Shanghai Expo ©Heatherwick Studio (2007-2010)

(left) Sou Fujimoto, Taiwan Tower competition winner ©Sou Fujimoto (unbuilt) (2011)

(right) Frederic Schwartz, The Rising, Westchester County 9/11 Memorial (2004-2006)

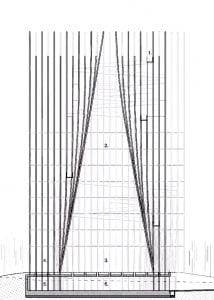

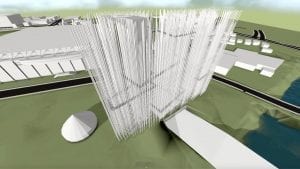

SMAR’s entry in San Jose also pushed the envelope, proposing the use of stainless steel rods that swayed in the wind at the top of the 20+-story structure.. In this case, it was clear that the team anticipated lots of questions concerning the structural viability of the design. But all of the questions put to them by the jury relating to that theme seemed to be addressed in the most highly technical, professional terms.

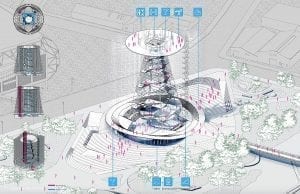

Stage 1 presentation rendering – ©SMAR Architecture Studio

As for the aesthetic value of the structure, there can be little question that it was an ideal fit for the site, setting up the ability to create various visuals based on a person’s location. As an opportunity to experience firsthand not only the forest idea presented by the rods upon entering the tower, its winding ramp to the top with several observation platforms allowed a participant to experience the activation of the the rods by the wind at its apex. The possibility to stage events and provide for exhibitions and other gatherings at the lower level would seem to be a bonus. This structure would also be no stranger to sustainability: enough electricity can be generated by the movement of the rods to satisfy the energy demands of the lighting program.

Aesthetically, the choice of the SMAR Studio design was quite logical: in architectural expression it certainly stimulated the imagination; because of the proximity of a large arena nearby, its relatively slim form as a vertical structure and placement within the site near the river created some breathing room. As an empty volume, it allowed for maximum flexibility to serve as a site for all kinds of events, exhibitions, weddings, etc. -Ed

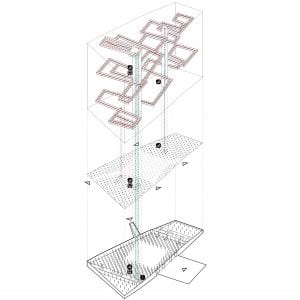

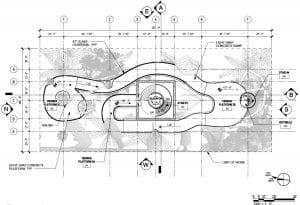

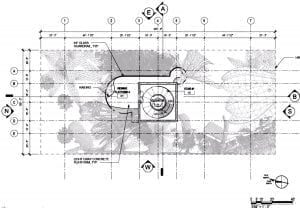

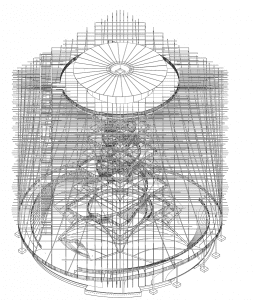

Construction Diagrams

Phase I interiors

All above images ©SMAR Architecture Studio

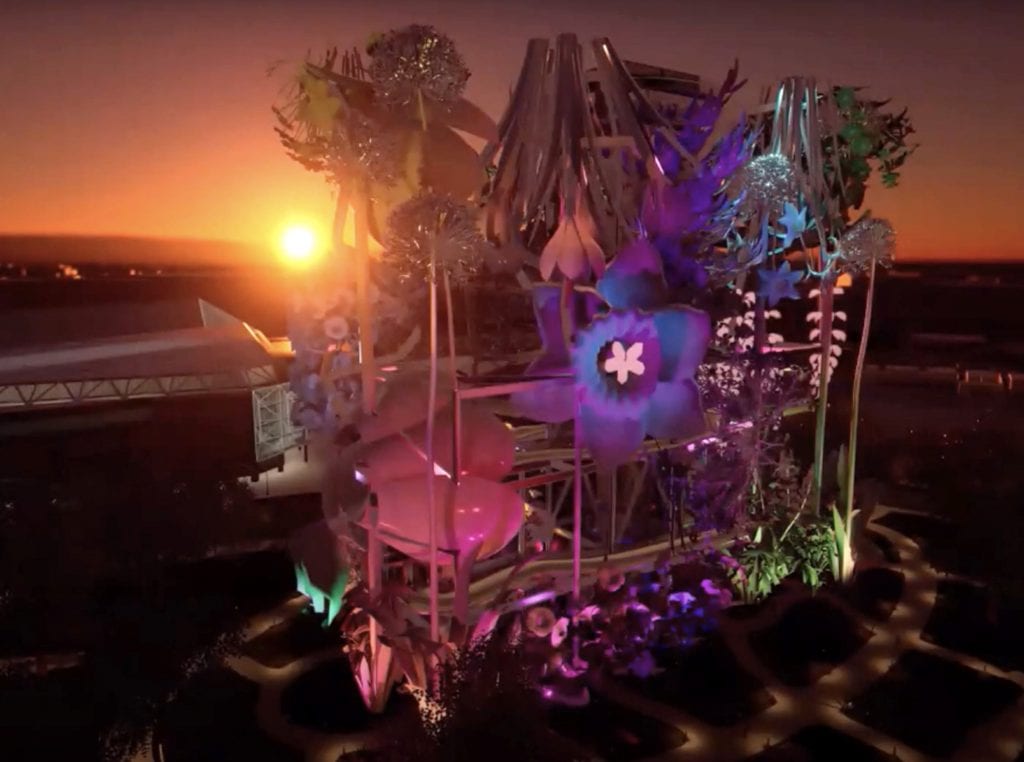

Finalist

Welcome to Wonderland

Rish Ryusuke Saito, SciArc, Los Angeles, California

Huitt-Zollars, Inc., Dallas, Texas (architecture)

Walter P. Moore (engineers), Houston, Texas

Todd McCurdy, FASLA, TMLA, York, Ontario

Josh Cottrell, CTS, Electrosonic, Inc., Sherman Oaks, California

Amy Pastor, PE, EXP (sustainability), Florida

Asif Parker, CPE, Cumming (themed entertainment), Aliso Viejo, California

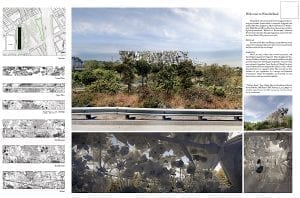

Phase 1 entry boards courtesy SJLTC

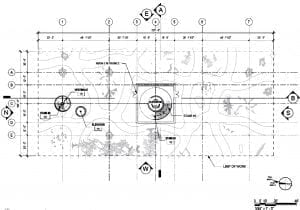

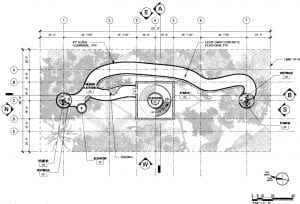

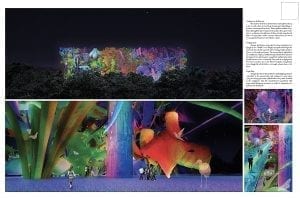

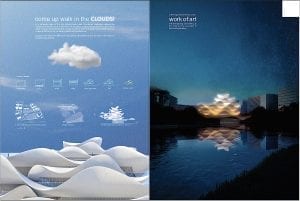

A recent student at Sci-Arc, Rish Ryusuke Saito’s design was partially the result of a project he developed there during a 2020 spring semester studio. This highly visual, artistically compact 700’ x 200’ x 700′ super-structure, draped with floral images, allowed for visitors to pass through it by foot on a transparent glass pathway. Completely white by day, it had to be more impressive at night, “when it would be transformed into a vibrant, immersive bouquet using holograms and projections mapping.

In the author’s words, “My project is full of unusuality; surreality. Once you see something beautiful, yet you feel uncomfortable, you may pay attention to it. The iconic landmark should have uncomfortability and ambivalent features of positivity and negativity—I’m using that dichotomy in a positive context.” Here we might assume that he is almost describing a jungle, beautiful, but probably threatening to an outsider, though a comfortable environment to one living there.

When HKS and the other members of the team stepped in during the final stage, some major changes took place. At the conclusion of the initial stage, which got the design to the finals, we were looking primarily at a horizontal, rectangular structure. Without the floral decoration, it probably could even have been regarded as a building type resembling a shed. The new design increased the height of the structure, so that one could travel to the top for viewing purposes.

For this site, it would seem to represent a rather unusual solution in that it represented a stationary art object. Although the team suggested that it might host a number of events, including art exhibits, the latter would seem to be a stretch, as any foreign art objects on display would find themselves in competition with the building itself. As a static structure, this proposal could be better understood on a smaller scale as an interesting artwork one might find as a temporary exhibit at the Serpentine Gallery in London’s Hyde Park. -Ed

Levels 3 (left) and 4 (right)

Above images courtesy SJLTC

Finalist

The Nebula Tower

Qinrong Lui / Ruize Li (co-designers)

Harvard GSD, Cambridge, MA / Singapore

HKS (architecture and engineering), Dallas, Texas

Martin/Martin, (engineering), Cheyenne, Wyoming

OJB Landscape Architecture, Houston, Texas

2nd phase view of tower from Arena Green – courtesy SJLTC

In the initial competition stage, this design by two young students from Harvard supposed a skeletal cube of 180’, whereby the repetition of the cubical theme is replicated to the interior of the structure. This allowed for various views from different perspectives for viewers, and could be adapted to interesting plays of lighting at night. The structural creation of an interior void harked back to the original San Jose light tower, the appearance undoubtedly enhanced by a cleverly conceived lighting program after dark.. Similar to the winning design, we also encounter here the inclusion of platforms at different levels for viewers.

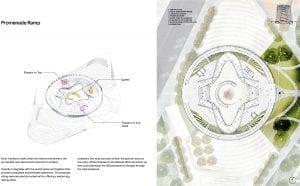

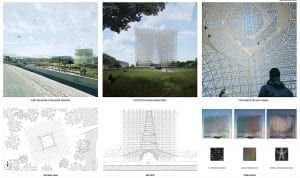

Phase 1 competition board ©Qinrong Lui / Ruize Li

The “lightness of form” noted by the authors was questioned by jurors during the initial phase, especially by Juror Jerry van Eyck, who stated that the “scaffolding” look he got from his original impression led to some convincing by other jurors to allow this design to rise to the status of a finalist. Enter HKS and the rest of the team in the second stage. The skeletal cube was now gone (above), supplanted by a more circular volume, whereby the hard edges had disappeared. Moreover, the design of the supporting elements of the superstructure now took on a more delicate look. The trained eye of the professionals had turned this entry into a major contender to be reckoned with.

During the jury presentation session, a question came from the jurors as to the necessity of adding two additional bridges to the overall program. Bridges are not cheap; and although they might be considered as something to be added in phases, budget concerns might have arisen here.

The improvements in the design, accompanied in the presentation by a 152-page booklet describing the project in much detail, were impressive and no doubt led HKS to decide to do—in Cesar Pelli’s words—”whatever it takes.” -Ed

Aerial view (left); View from Arena Green (right) – courtesy SJLTC

In all due recognition to the 963 designers who entered the competition, the wide range of schemes included many that did not follow the “tower” concept. Two of those that were included among the 47 that were identified by the Community panel as worthy are shown below:

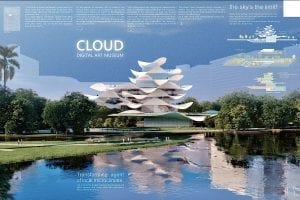

#0357 – Cloud Digital Art Museum

Unless otherwise noted, above images courtesy SJLTC