Not to be outdone by other Canadian provincial capitals, Halifax has chosen to make its own ambitious museum statement on the city’s waterfront. New museums in Vancouver, BC, Calgary and Fredericton, New Brunswick, the latter two by KPMB Architects, are either in development or already under construction. Saskatoon’s Remai Modern by KPMB and OMA’s Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec in Montréal were more recently completed, and Vancouver’s new Art Museum by Herzog & de Meuron is still under development. To assure a high quality result, the Halifax authorities, with Montréal as an example, turned to an invited design competition in two stages: the first stage being a call for qualifications, whereby three firms were shortlisted:

• KPMB with Omar Gandhi (Toronto) and Public Work (Landscape Architecture) ;

• Dialog (Winnipeg/Toronto) with Brackish Design Studio (landscape architecture)

• Architecture49 with Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DSR) and Hargreaves Jones (Landscape Architecture)

With the possible exception of the Architecture49 team, both the KPMB/Omar Gandhi and Dialog teams were notable for their serious nod to the Mi’kmaw culture, including members of that tribe on their teams. Here it is notable that the inclusion of Omar Gandhi on the KPMB team matched up with Gandhi’s considerable experience in Nova Scotia and undoubtedly may have contributed to the inclusion of the Mi’kmaw artist, Jordan Bennett and First Nation celebrity, Elder Lorraine Whitman, on their team.

The Adjudication Process

According to the competition brief, the following project objectives were highlighted:

1. A Welcoming Visitor Experience

2. Programming with and for the Community

3. Strengthen our Identity

4. Public Space and Art

5. Uniqueness

6. Sustainable Design

7. Functionality

8. Professional Standards

9. Rental and Special Event Venues

10. Art is Everywhere

To survive the final adjudication process, the designs were examined based on the following criteria:

• Overall quality of the proposed design;

• Capacity of the proposed design to achieve the objectives for the New Art Gallery of Nova Scotia and public space as part of a Waterfront Arts District as described in the design brief;

• Capacity of the proposed design to achieve the technical and performance targets identified;

• Capacity of the proposed design to meet the construction budget and cost effectiveness of the proposal.

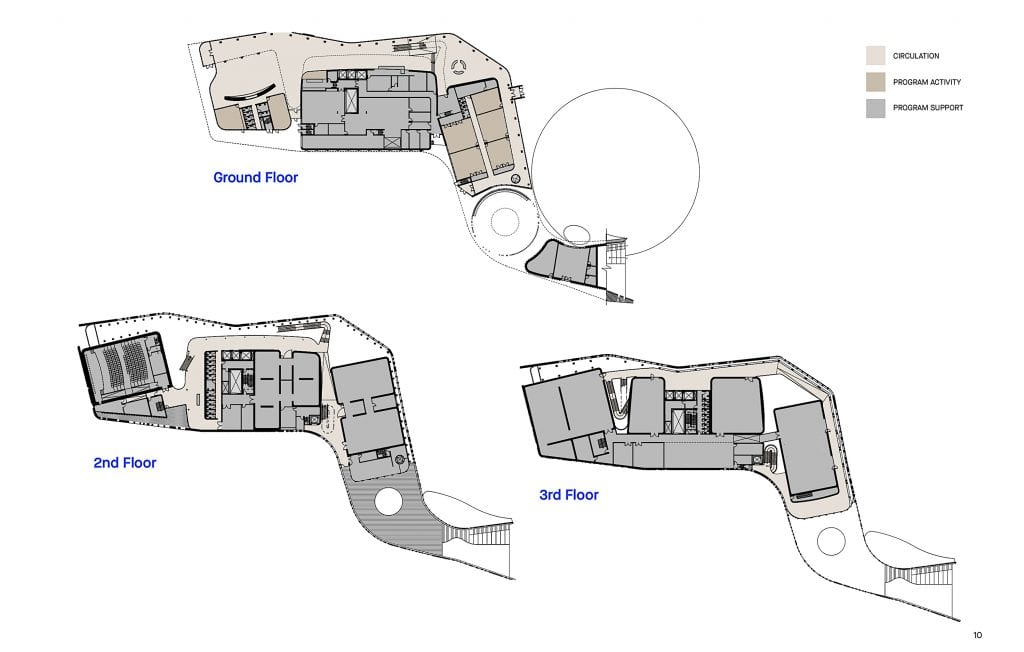

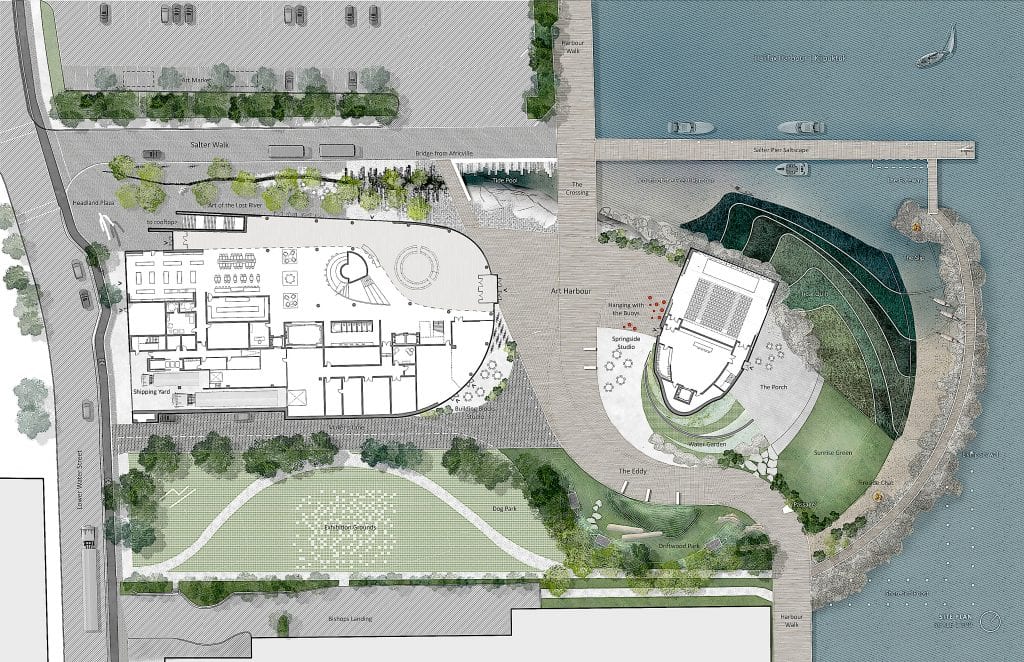

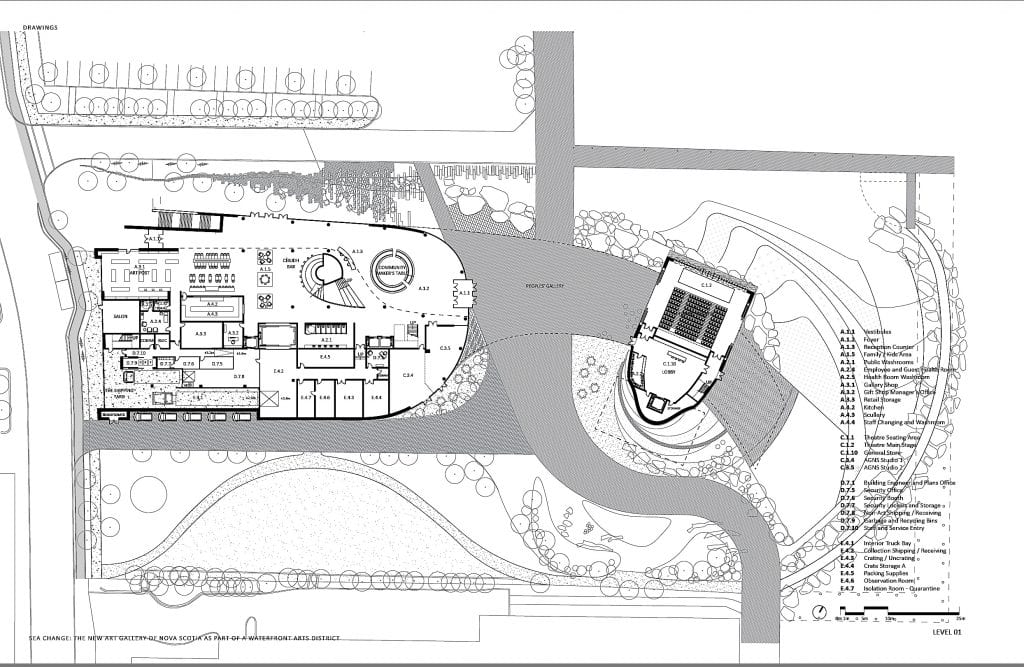

Site plan – Image: ©KPMB Architects

Jury

The jury was made up both of design professionals and stakeholders:

• Claude Cormier, Landscape Architect, Principal Associate, Claude Cormier + Associés, Montreal

• Sylvia D. Hamilton, Artist, Filmmaker, Writer, Inglis Professor, University of King’s College, Halifax, Nova Scotia

• Gregory Henriquez, Architect, Managing Principal, Henriquez Architects, Vancouver, British Columbia

• Francine Houben Architect, Founding Partner/Creative Director, Mecanoo, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

• Ursula Johnson, Ursula Johnson, Interdisciplinary Artist, South Brookfield, Nova Scotia (originally from Eskasoni First Nation in Cape Breton)

• Nancy Noble, CEO and Director of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, Halifax, Nova Scotia

• Claire Weisz (Jury Chair), Architect, Founding Partner/Principal in Charge, WXY Architecture + Urban Design, New York City, USA

The Final Decision

All of the finalists presentations had some things in common, most obvious being the liberal use of wood, especially in the interior. All three used the boardwalk as an idea to frame the approach from the ocean, thereby extending the site visually beyond the water’s edge. Only in the case of the KPMB proposal was it unclear whether the harbor walk would be routed offshore, instead of leading past the front of the main building. But when it came to architectural expression, the three designs differed markedly.Here we must note that the jury’s released report only dealt with KPMB’s winning design. So we were left guessing as to their ideas concerning the other two finalists. Aside from the issue of diversity, the only reference the jury made to their deliberations concerning all of the entries was as follows:

“A design competition captures a short moment in time, and the jury would like to acknowledge that the work produced by all three teams in only 10 weeks is nothing short of incredible. There were, however, areas of concern in all three of the designs related to art display, circulation, and art handling which dominated parts of the jury discussion.”

Architecture49 and DSR’s approach was to spread out over most of the site, using a cantilever system at the building’s third level to delineate individual spaces at irregular intervals. This strategy harked back to the DSR’s cantilevered second level at Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art, which drew much attention when it opened in 2006. This gesture did provide visitors with multiple viewing opportunities, both to the ocean as well as to the city. It would appear that the wayfinding issue is well developed in this plan.

Beginning with an approach to Dialog’s building from the city, its appearance evolved from a somewhat ordinary urban facade to a colorful, then undulating sculptural form. Together with its colorful panels, there could be no mistake as to the mission it wanted to project, supported by a Henry Moore-like sculptural gesture at the far end: it’s all about art! Still, the dramatic cut in the colorful facade suggests multiple entrances to the museum, in a sense underplaying the main entrance. Also, the loading dock facing on the main street is a distraction for visitors on their way to an otherwise interesting experience.

The undulating, sculptural theme was carried to the interior, where wood was used as the primary material. Instead of a contiguous building at grade, the lecture hall was situated at the very end of the main building, separated from the main structure at grade, which allowed for unimpeded access underneath for those using the Harbor Walk.

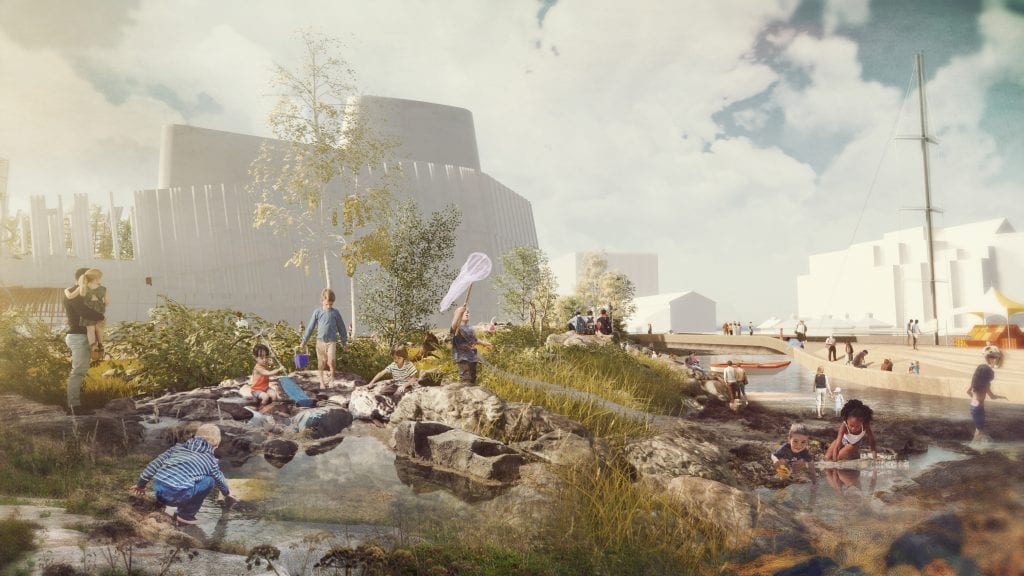

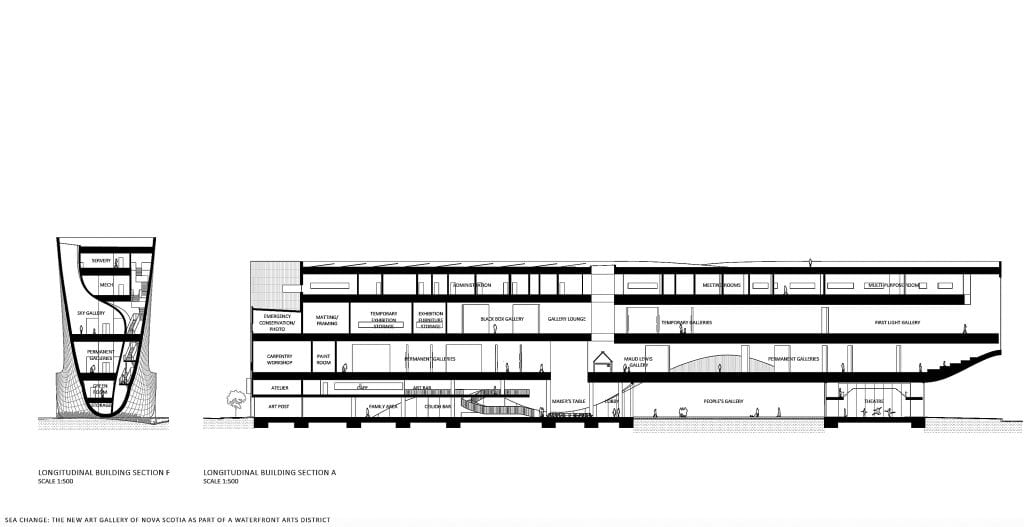

KPMB’s winning design’s emphasis on Mi’kmaw culture could almost have been interpreted as an exercise in connecting architecture with anthropology. Starting with the main entrance in the form of a woman’s peaked hat, the exterior reference continued with the use of terracotta panels to reference an eel’s skin, leading down to the harbor. Of course, this abstract form would have to be explained to an unsuspecting visitor—regardless of its logical function as a descending path leading to the harbor. An impressive Mi’Kmaw reference was the circular Oculus, an open air, partially sheltered gathering place.

The jury did admire the museum’s main entrance and the canted timber “diagrid” that framed the public space on the inside. In their words,

“The design used beautiful forms and materiality to create a seamless integration from building to landscape. “There seems to be an elegance”. The team made “a beautiful beacon on the shores of Halifax.” The design answers the request to be local, “even though shape may well change….[the design] will be attractive to the eye, people will want to know what that is, and they will want to go to it.” The scale, use of wood, and the light is compelling. It has a rapport with the street that is open and on cue with the landscape, while finding its place in the urban setting.

This design has the most potential for people to engage with it in a compelling way. The forms are free-flowing, organic, where the space outside of the art spaces, has no start and stop. The design is unique and takes its inspiration from natural phenomenon. The design team understands the issue of the site and the context,”

Impressed by these gestures as relating to local culture, especially in their context, the jury noted that the Mi”kmaw were not involved directly as sponsors of the project, but should be included as partners in its further development. Some concern was voiced by the Jury as to the current design’s ability to fit into a fixed budget of $150M. One can only hope that any value engineering that might occur would not diminish the design’s impact, both spatially and aesthetically. -Ed.

Winner

KPMB Architects with Omar Gandhi

and

Jordan bennett Studio (artist)

Public Work (Landscape Architect)

Transolar

Elder Lorraine Whitman (NWAC)

Toronto/Nova Scotia

Unless otherwise noted, all above images: ©KPMB Architects

Finalist

Architecture49 with Diller Scofidio + Renfro

Hargreaves Jones (Landscape Architects)

Halifax/New York/San Francisco

Unless otherwise noted, all above images: ©DSR

Finalist

DIALOG

with

Acre Architects

Brackish Design Studio (Landscape Architecture)

Shannon Webb-Campbell (Diversity consultant)

Toronto/Halifax

Unless otherwise noted, all images ©DIALOG