The O’Hare International Airport Competition

The updating and modernization of Chicago’s O’Hare Airport has been well overdue. Aside from occasional problems caused by Chicago’s winter storms, congestion at the airport has led air travelers to avoid the airport when catching a connecting flight is on the agenda. So Chicago, noted for its modern architecture and the home of several high-profile architecture firms, decided to turn to an invited competition for a solution to these issues.

Competitions in Chicago in the recent past have been anything but encouraging, especially when transparency is an issue. During the competition for the Obama Center on the South Side, the Obama Foundation, which was responsible for the administration of that “competition,” was anything but a model of transparency; and to this day, none of the finalist designs, other than that of the winner, have seen the light of day. In the case of the O’Hare project, videos submitted by the five finalists teams were on public display, and the public was even asked to vote for their favorite.

The five teams shortlisted for the competition were:

• Studio ORD – Studio Gang, Solomon Cordwell Buenz, Corgan, Milhouse Engineering and STL Architects

Chicago

• Fentress Architects, EXP, Brook, Garza

Denver

• Skidmore Owings & Merrill (SOM)

Chicago

• Foster Epstein Moreno

London/Chicago

• Santiago Calatrava

Zürich

This list is notable for who was there, and who was not. The lone Chicago firm with lots of expertise in this area not included was Jahn, which has been the author of some important airport projects in Germany—Munich and Frankfurt in particular—as well as its well received addition to the American Airlines Terminal at O’Hare several years ago.

Others include Rogers Stirk Harbour (RSH) of London—architects not only for the new Madrid airport, but a competition winner for Taiwan’s Taoyuaong Airport Terminal 3 over U.N. Studio and Foster and Partners;* Renzo Piano (Kansai International Airport); Massimiliano and Doriana Fuksas (Shenzhen Bao’an International Airport); and Zaha Hadid Architects (Beijing Daxing International Airport).

Of the five shortlisted firms with airport expertise, only the eventual winner ORD21, has had little experience with airport projects of this magnitude. The leader of the team, Studio Gang, therefore teamed with another Chicago firm with much experience in large projects, Solomon Cordwell Buenz. The inclusion of Foster, Fentress,** and SOM is logical in view of their numerous, high-profile projects. As for Calatrava, although the firm does have an airport in its portfolio, extreme cost overruns in other projects—Milwaukee Art Museum and New York’s Oculus at Ground Zero in particular—may have given other clients pause. When the Oculus overruns were mentioned on the Chicago website, Curbed, Calatrava insisted it was all the result of security concerns that arose after terrorist attacks had occurred.

The results of the voting by the public, based on the videos, were hardly surprising: almost half voted for Calatrava, whereby the two Chicago firms, SOM and Studio-ORD didn’t fare well at all. Calatrava almost always does well in a beauty contest, but is less convincing to experts in the field when the project is examined in full detail. Here it would have been instructional for public understanding of the final decision if all of the entries could have been supplemented with extensive jury comments. But again, who was the Chicago jury?

* “An Illuminating Experience” in 2015 COMPETITIONS Annual, pp. 8-25

** “Variations on a Theme: Americans Win Airport Competition on the Pacific Rim,” by Roger Chandler in COMPETITIONS, Volume 3, #2 (1993) pp. 30-42 This airport in the Seoul metropolitan area now is designated as Incheon International Airport.

Winner

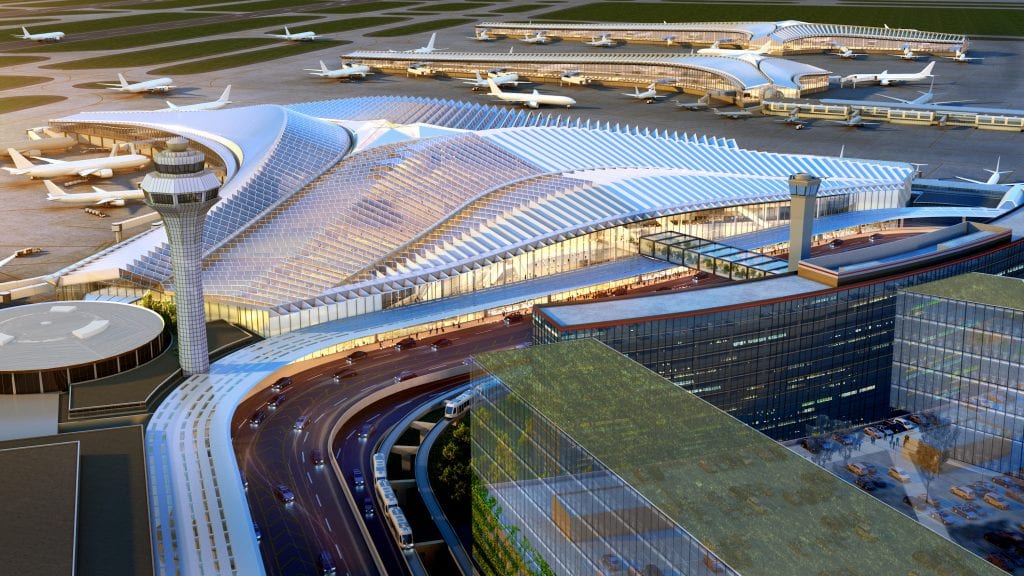

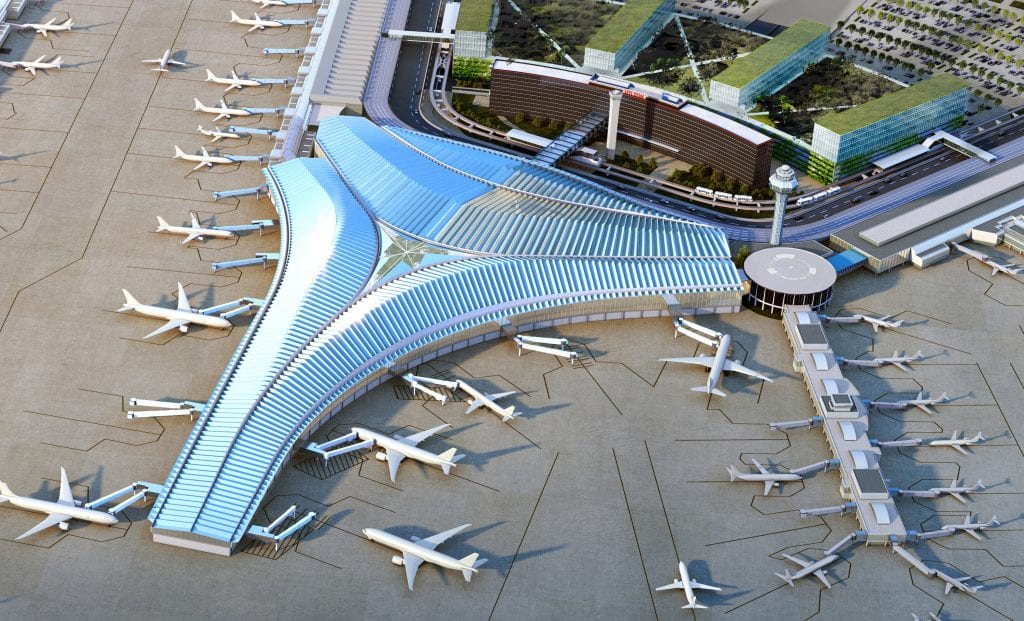

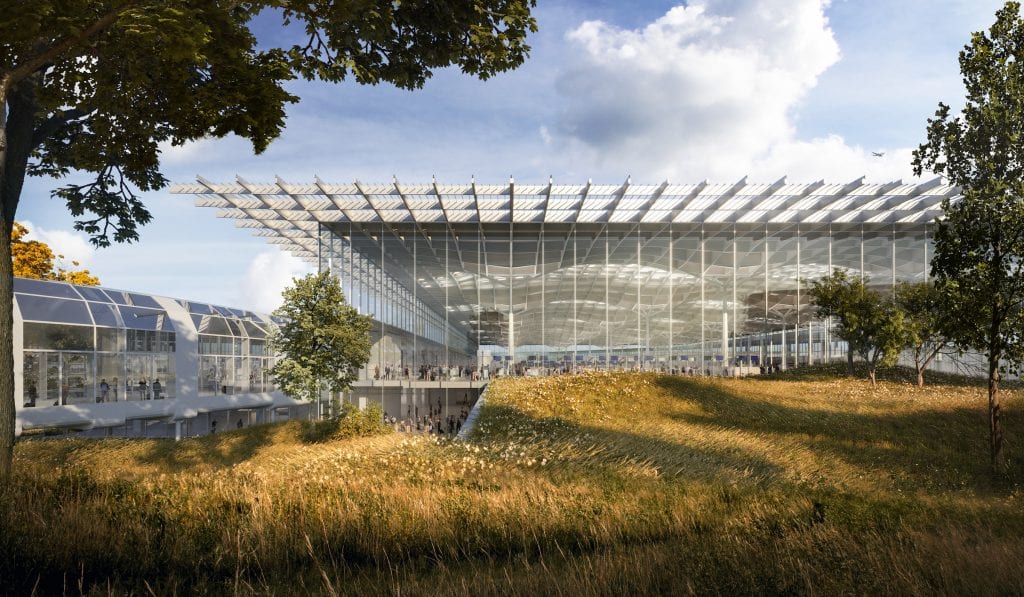

Studio-ORD – Studio Gang, Solomon Cordwell Buenz, Corgan, Milhouse Engineering and STL Architects

Chicago

Above Images: courtesy Studio Gang ©Studio – ORD

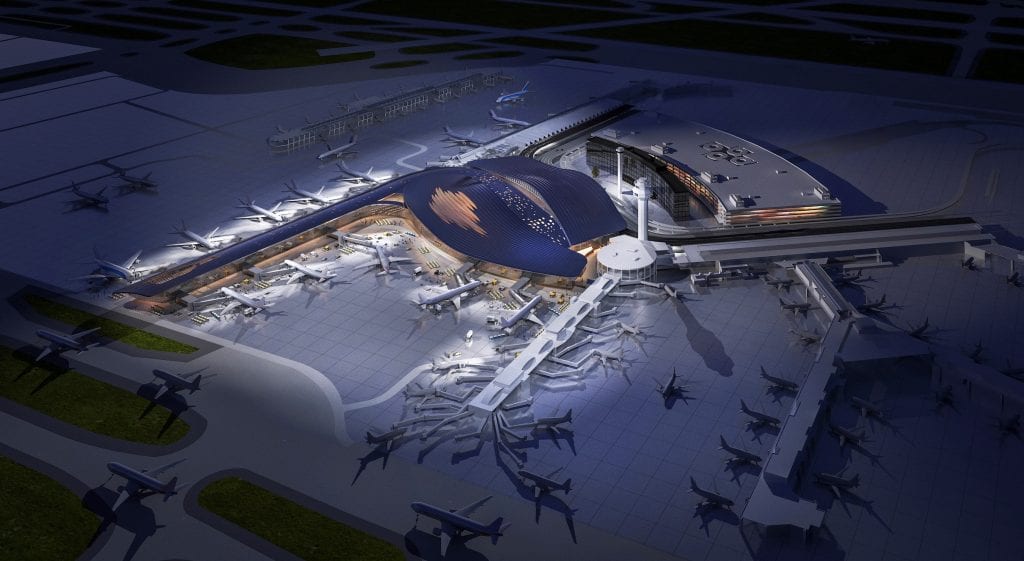

Runnerup

Skidmore Owings & Merrill (SOM)

Chicago

Finalist

Fentress Architects, EXP, Brook, Garza

Denver

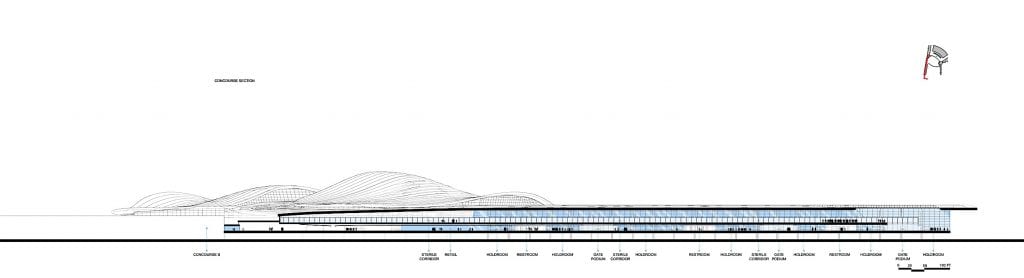

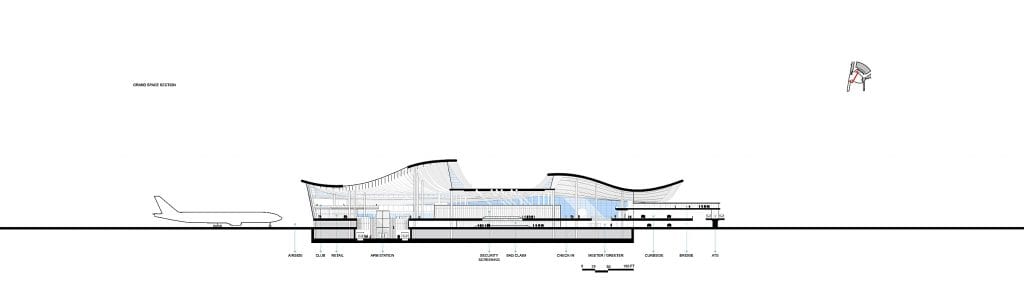

Cross section

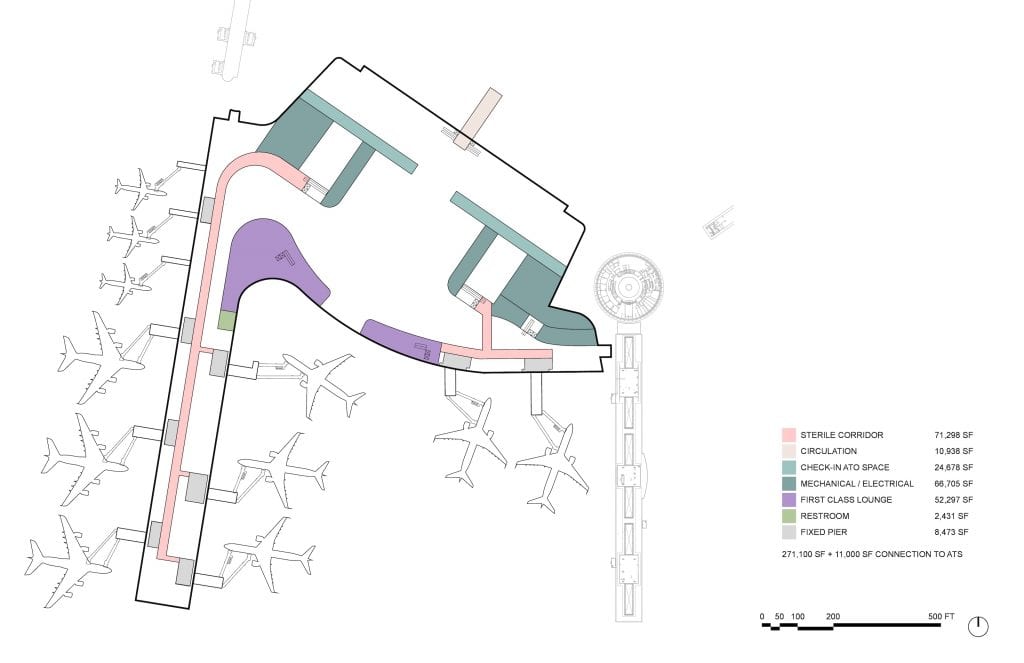

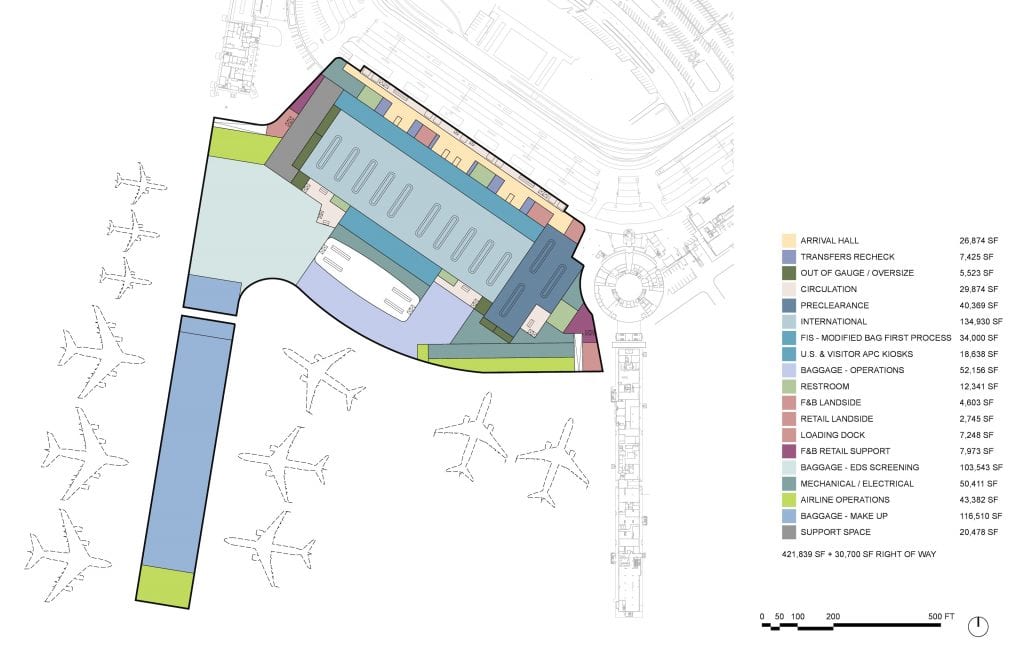

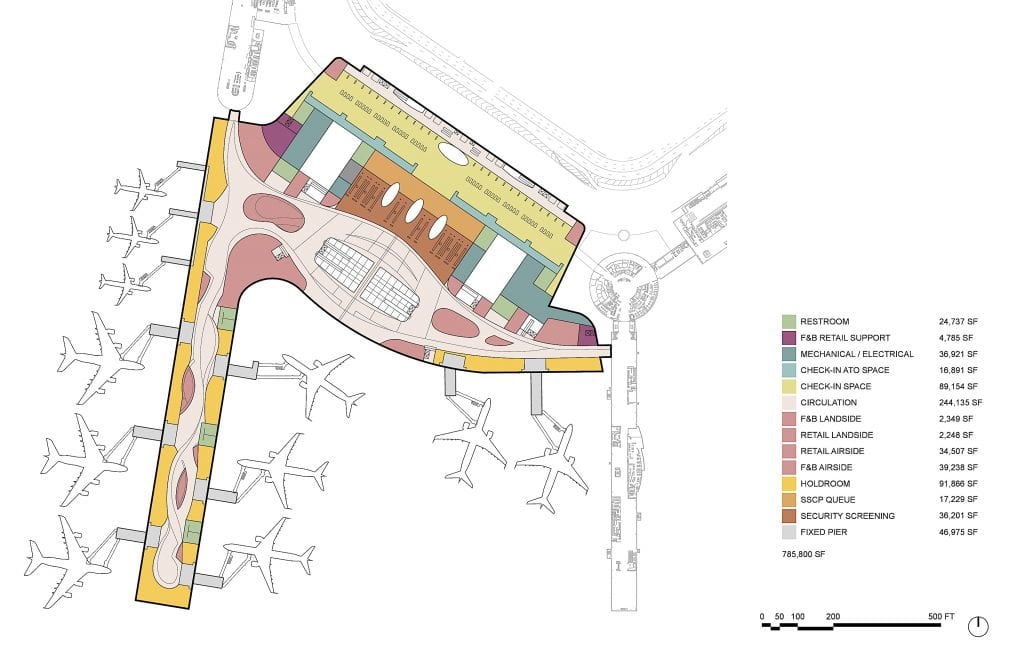

Basement (left, above); Lower Level (right, above)

Upper level (above); Mezzanine level (below)

Above Images: courtesy ©Fentress Architects

Conclusion

The winning Studio—ORD project distinguished itself from the others in its use of wood as a primary design feature. Whereas SOM used it sparingly as a strong element in elevating the value of the visual appearance in certain areas of the terminal, Studio-ORD featured it throughout in a two-fold manner: as a structural element in the ceiling, separated by glass panels, and in various totally enclosed areas, both in the ceiling and elsewhere—as behind the ticketing counters. Most architects and frequent flyers we interviewed found the use of the closed timber approach disinclined to visually result in a positive effect on the common passenger. On the other hand, there was universal praise for the use of trees and vegetation to soften the landside to airside passage, in contrast to many airport terminal interiors where one may encounter a somewhat sterile environment. Could the low popular rating of this design by the public vote be attributed to this single feature? Based on our research, most probably. Several architects questioned on this subject assumed that Studio-ORD was trying to make a strong sustainability statement. As for the SOM scheme—chosen as the runnerup to design the satellite terminals—and Fentress Architect’s proposal, their designs logically have much in common with past winning performances: SOM’s CHhatrapati Shivaji Airport in Mumbai, India was mentioned by some, and Fentress Architect’s Incheon Airport, serving Seoul, Korea certainly came to mind. Both airports have received high grades and undoubtedly led to their author’s survival via the shortlisting process as finalists. -Ed

Note: Calatrava and Foster did not respond to our request for images.