Competing for an Arrival Experience and Plan at UCD

Winning design: Image:©Steven Holl Architects and Malcolm Reading Consultants

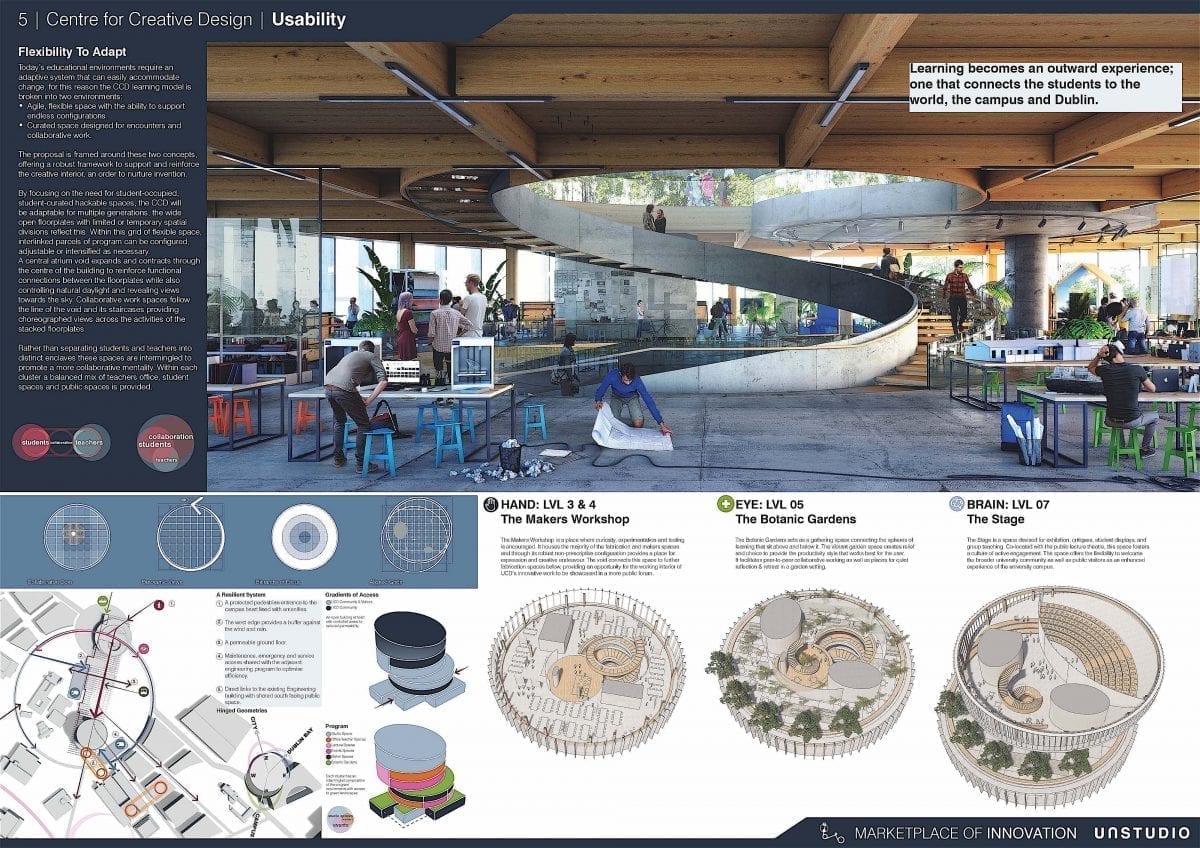

A designer of hospitals once remarked that a full vacant floor should be added to every new hospital facility to accommodate the rapid changes in the technical demands of the industry. Although on a different scale, the same might now be said of architecture programs at universities, as the addition of everything connected with computer technology—i.e., computer 3D modeling—has led to changes in instruction and curricula in academic architecture programs. Providing empty space in a new building without a true purpose would run into problems with the people controlling the purse strings, as they want to see the justification for every square foot of programmed space. But the recognition of this factor was foremost in the minds of the client and many of the competitors in the Future Campus UCD competition in Dublin. While some left space for future expansion, others revealed less emphasis for flexibility in their approach to the challenge presented by the Center for Creative Design at the campus entrance—and this included the winner.

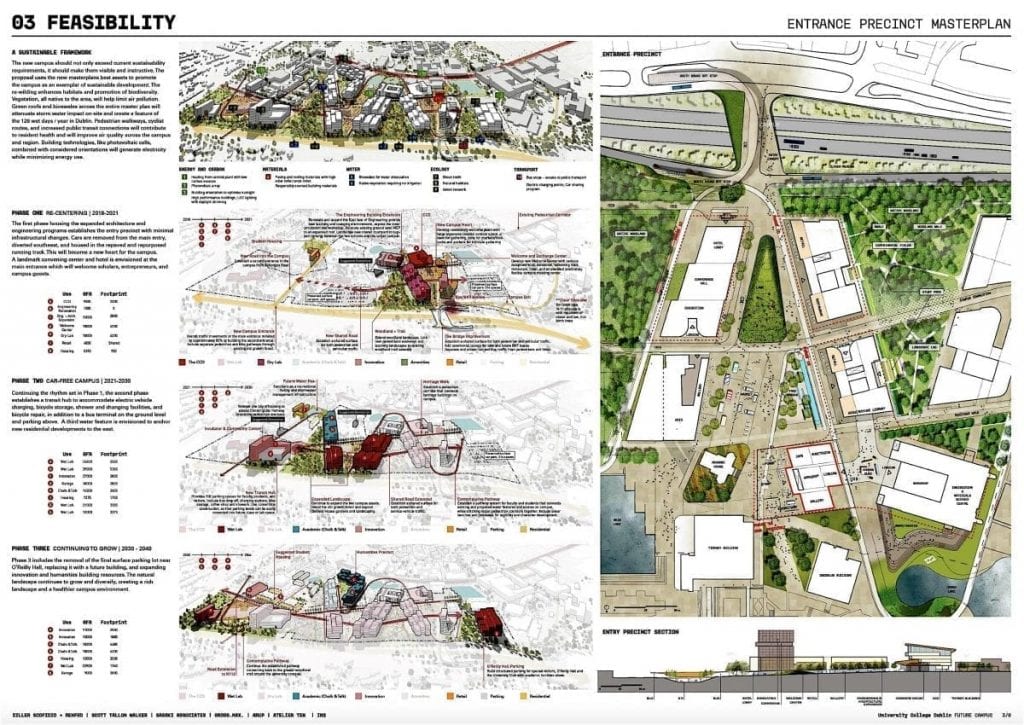

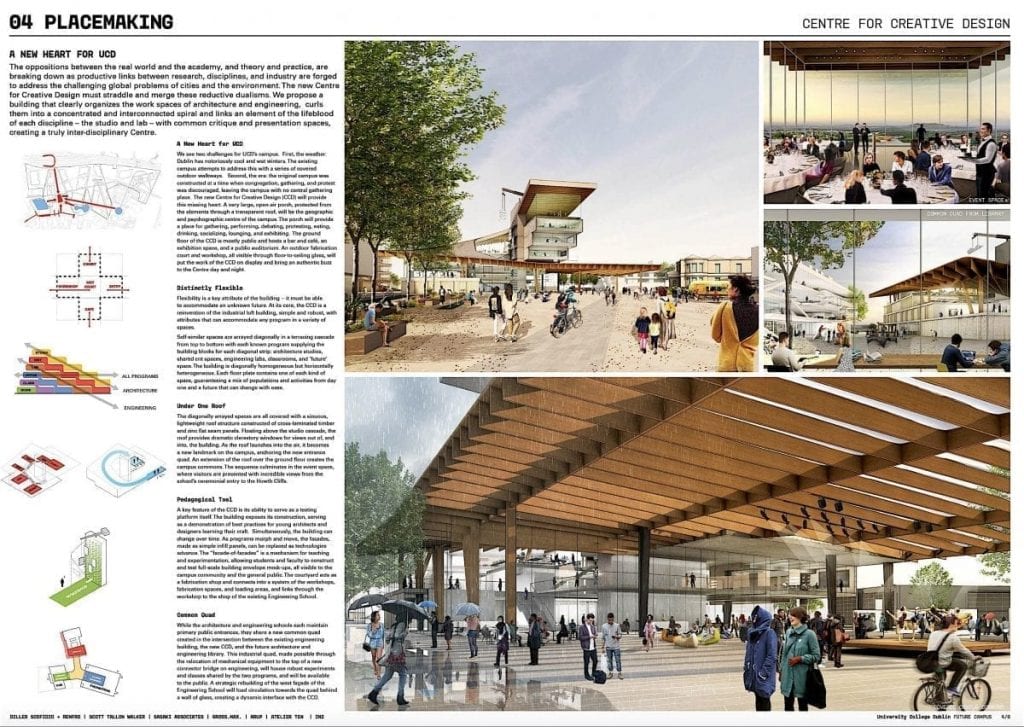

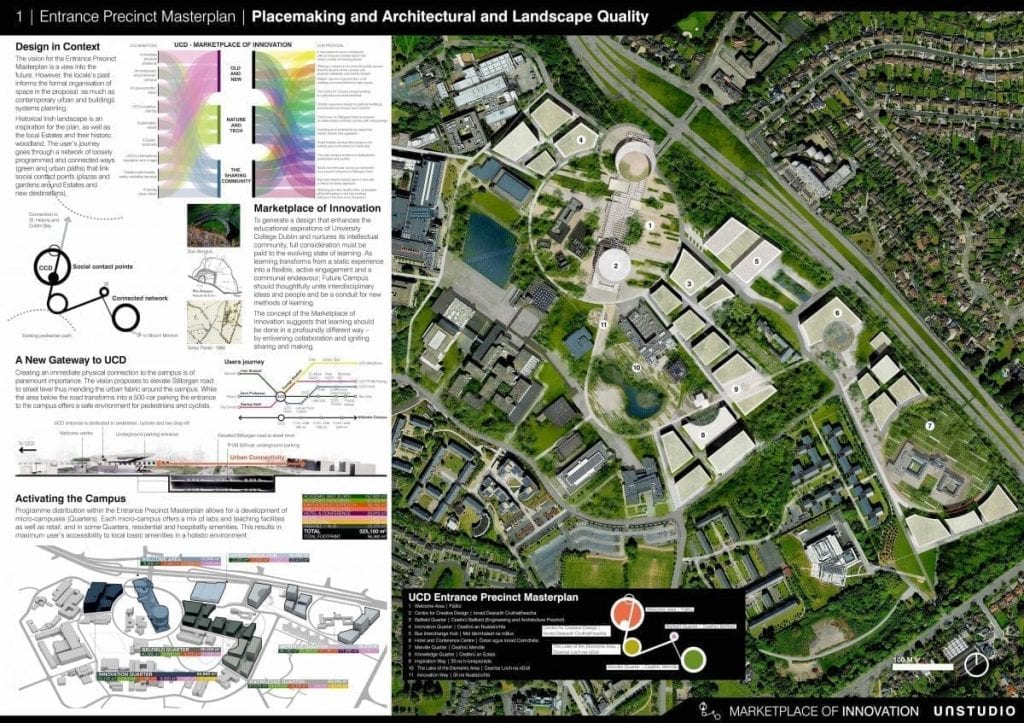

The emphasis on an arrival feature was clear from the competition brief:

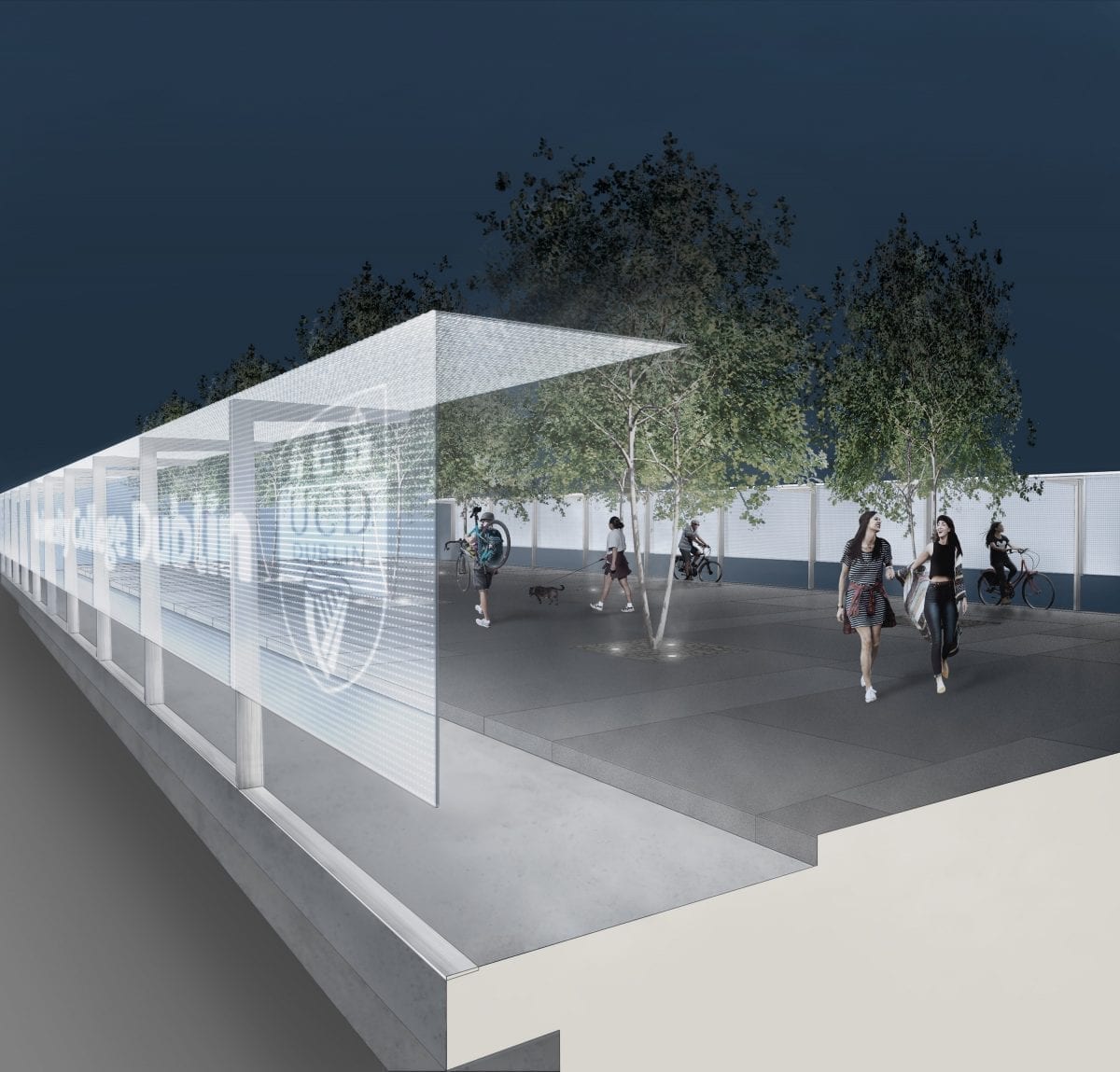

“The brief to competitors was to draw up an urban design vision that foregrounds a highly-visible and welcoming entrance precinct, and create a concept design for a charismatic yet integrated new 8,000 sqm building – the Centre for Creative Design – that expresses the University’s creativity. The Future Campus project is intended to create a stronger physical presence and identity for the University within Dublin, and raise the profile of UCD nationally and internationally.”

The purpose of the competition was to expand and update a rather nondescript area with an arrival feature for campus expansion, with strong emphasis given to site planning. The appearance of an “arrival experience,” both symbolically and spatially, was to provide the campus with an unmistakable landmark to deal with the current “underwhelming experience.” The selection of the six high-profile finalists for this invited competition was also a certain signal that this building was to be anything but traditional in character. Thus, the competitors did not have to consider the possibility of a local jury insisting on “context” as a primary guideline for architectural expression—although context curiously did enter the discussion.

The Interdisciplinary Issue

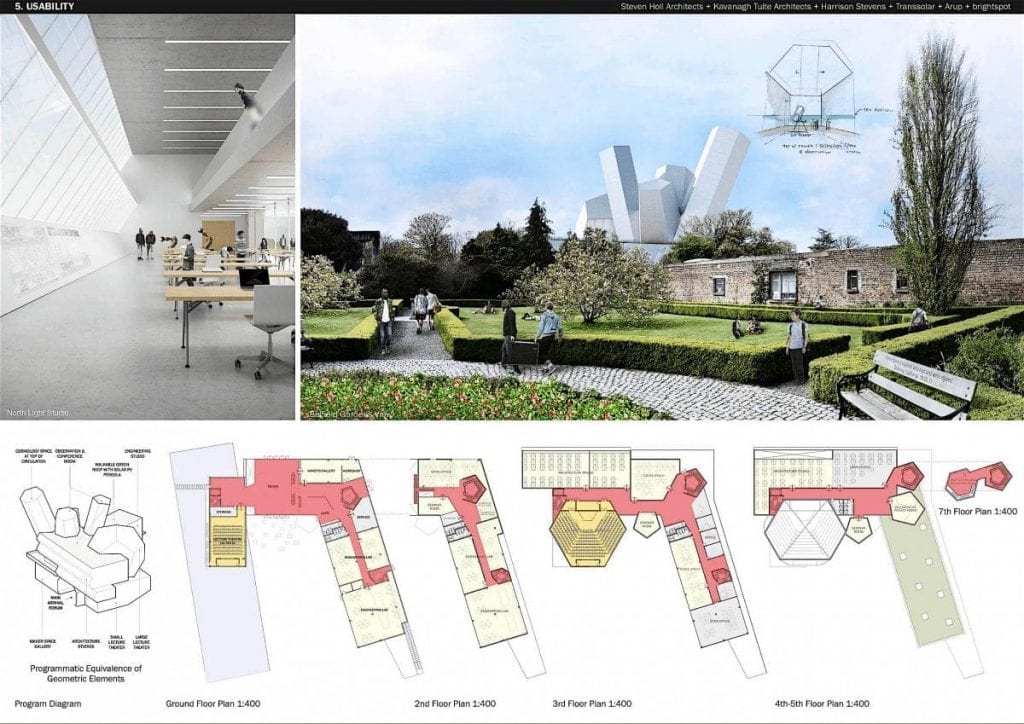

As has often been the case with the programming of recent academic facilities throughout the world, interdisciplinary contact between different majors was also in the forefront here. Thus we see many of these designs locating architecture and engineering programs on the same floor. An exception here was the winner, who located engineering on the bottom two floors of the building, with architecture on above floors.

Studios for recent architecture programs at numerous universities have been located on one, large level, often at grade—promoting interaction between students at different levels as well as faculty. This includes recent U.S. schools of Architecture, i.e., Florida International University, Ohio State University, Kent State University, University of New Mexico, etc. The logic of making a major arrival statement with a significant building in this case suggests a multi-story building with limited square footage at each level. Thus, many of these competitors could be seen following the high-rise formula—resulting in more fragmentation in the organization of the teaching areas.

Winning design: Image:©Steven Holl Architects and Malcolm Reading Consultants

The competition was organized under the supervision of Malcolm Reading Consultants, London. Ninety plus firms submitted qualifications in the RfQ process, which resulted in the shortlisting of the six finalists. They were:

• Diller Scofidio + Renfro, New York

• John Ronan Architects, Chicago

• O’Donnell + Tuomey, Dublin

• Steven Holl Architects, New York

• Studio Libeskind, New York

• UNStudio, Amsterdam

Each finalist team received an honorarium of €40,000 for their competition work, and the international teams were required to team up with a local executive team for the second stage.

The jury consisted of five design professionals and six academics and laypersons:

• Professor Andrew J. Deeks (Jury Chair), President, University College Dublin

• David Adjaye, Principal, Adjaye Associates

• Ann Beha, Principal, Ann Beha Architects and Member, Harvard University Design Advisory Panel

• Joe Berridge, Partner, Urban Strategies, Inc.

• Professor Hugh Campbell, Professor of Architecture, Head of Subject and Dean, School of Architecture, Planning & Environmental Policy, University College Dublin

• Dermot Desmond, Chairman, International Investment & Underwriting

• Professor Orla Feely, Vice-President for Research, Innovation and Impact and Professor of Electronic Engineering, University College Dublin

• Professor David P. FitzPatrick, Principal, College of Engineering & Architecture and Dean of Engineering, University College Dublin and Provost, Beijing-Dublin International College

• Professor Michael Monaghan, Vice-President for Campus Development, University College Dublin

• Sean Mulryan, Founder, Chairman and CEO, Ballymore

• Dr Paul Thompson, Vice-Chancellor, Royal College of Art, London

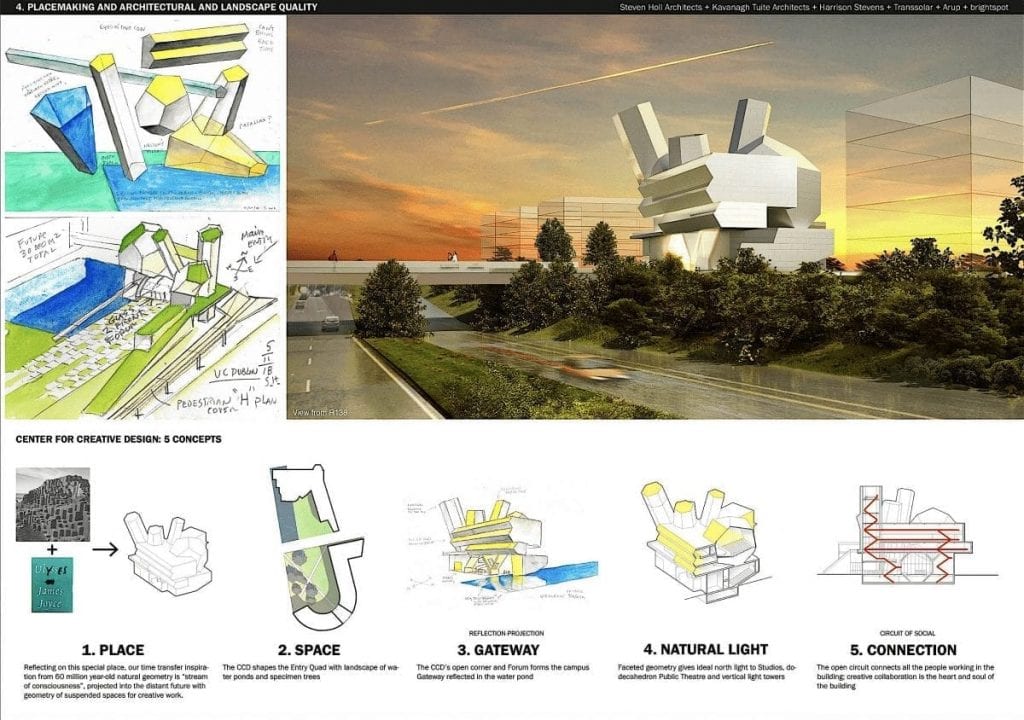

Commentary about the winning design by Steven Holl Architects is relatively brief in the absence of a jury report. But the press release suggests that placemaking was just as important in the jury’s decision as was the architectural expression of Holl’s building:

“Holl’s vision is intriguing and striking – combining an iconic design for the Centre for Creative Design with a masterplan distinguished by a few considered, highly intelligent moves that open up the centre of the campus and use creative landscaping to intensify its natural beauty.”

– Professor Andrew J. Deeks, President of University College Dublin and competition Jury Chair

Winner

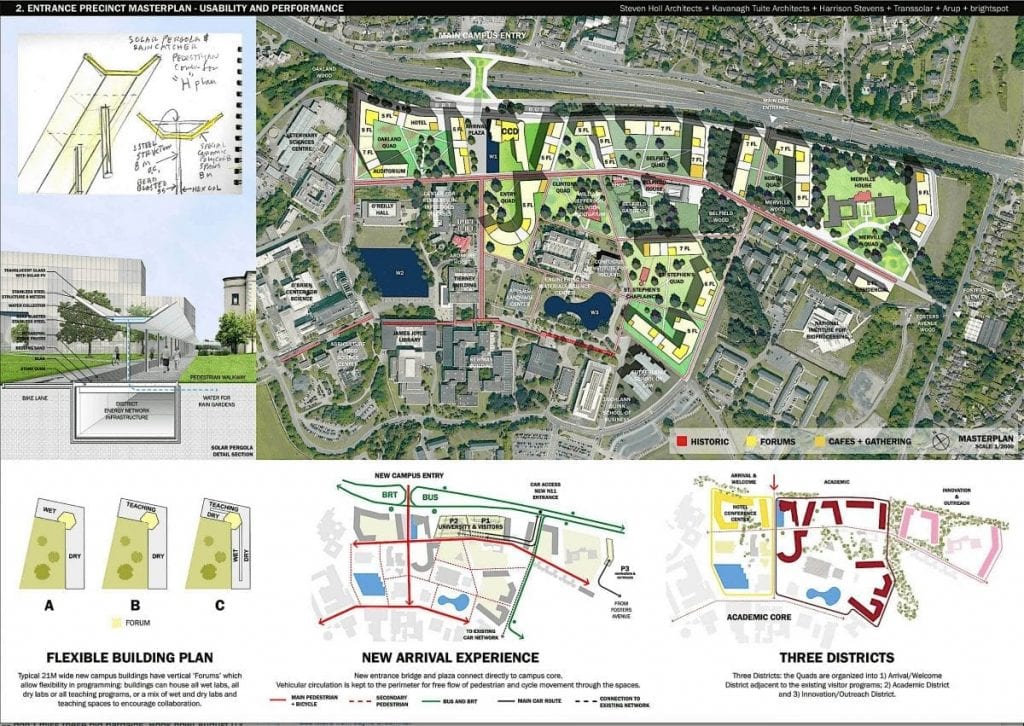

Steven Holl Architects (US) with Kavanagh Tuite Architects, Brightspot Strategy, Arup, HarrisonStevens and Transsolar

All above images: ©Steven Holl Architects / Malcolm Reading Consultants

Steven Holl’s abstract sculptural interpretation of the CCD building is certain to draw attention as an arrival feature. He may have drawn his deconstructivist theme from the “geometries of Giants Causeway and the work of James Joyce.” Still, by referencing (and justifying) the origins of his design based on a remote exterior element places him in the territory of a Peter Eisenman, who referenced the skewed siting of the Wexner Museum to a distant grid most people were unaware of. Also, by settling on a design for a building with protruding elements jutting from the top, he ended up with a structure designed at least partially from the outside in, rather than inside out. This resulted in some areas with organizational fragmentation, most notably in the separation of architecture studios from engineering on separate levels—a departure from recent successful examples of one-level studio areas in other programs (see above). And by locating engineering on the bottom two floors and architecture on the two stories above, the interdisciplinary connection between these two disciplines is pretty much ignored.

Site planning by the Holl team was more convincing, as the pathways leading to different areas were well conceived, covered by canopies leading from one area to another and lined with solar panels. The quadrangle idea for neighboring structures is a logical formula, breaking up the campus site into smaller modules, rather than larger structures, which makes for a more lively campus setting in its reference to academia.

Based on the mid-rise nature of the building, some of these issues could well be addressed in design development. -Ed

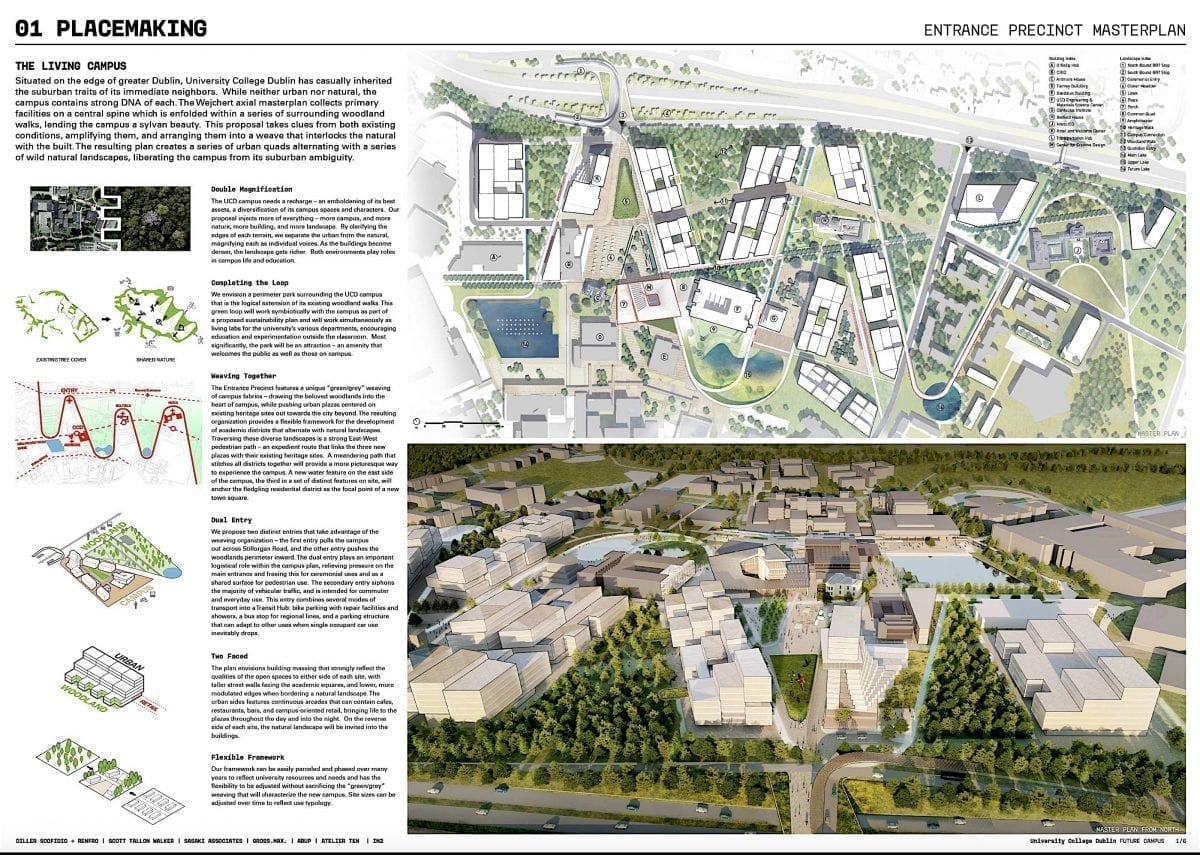

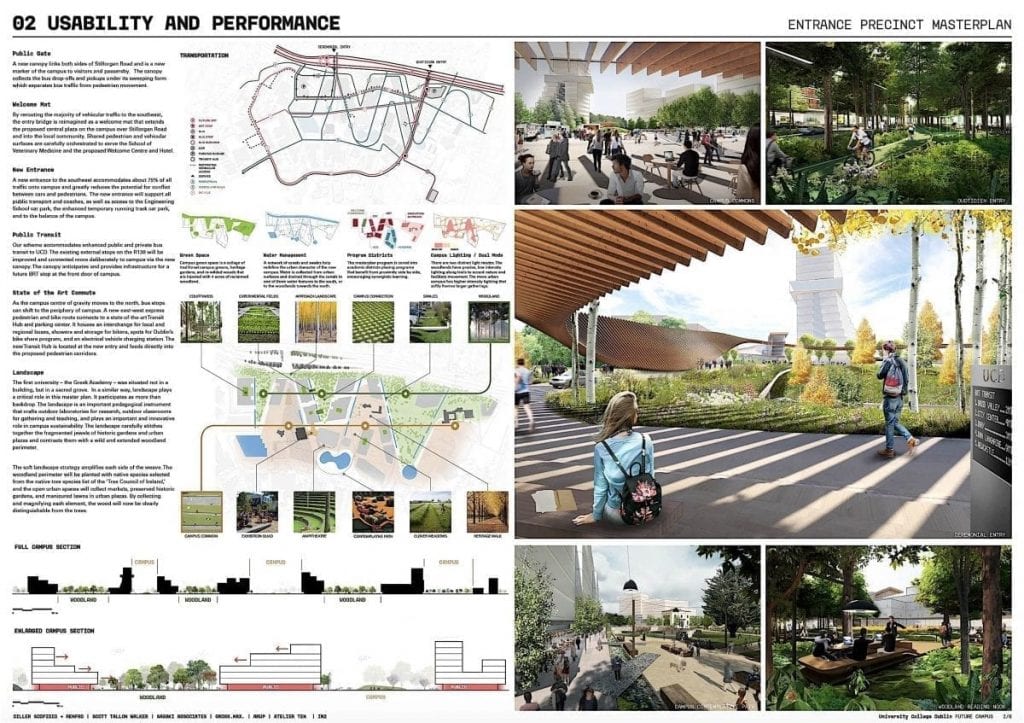

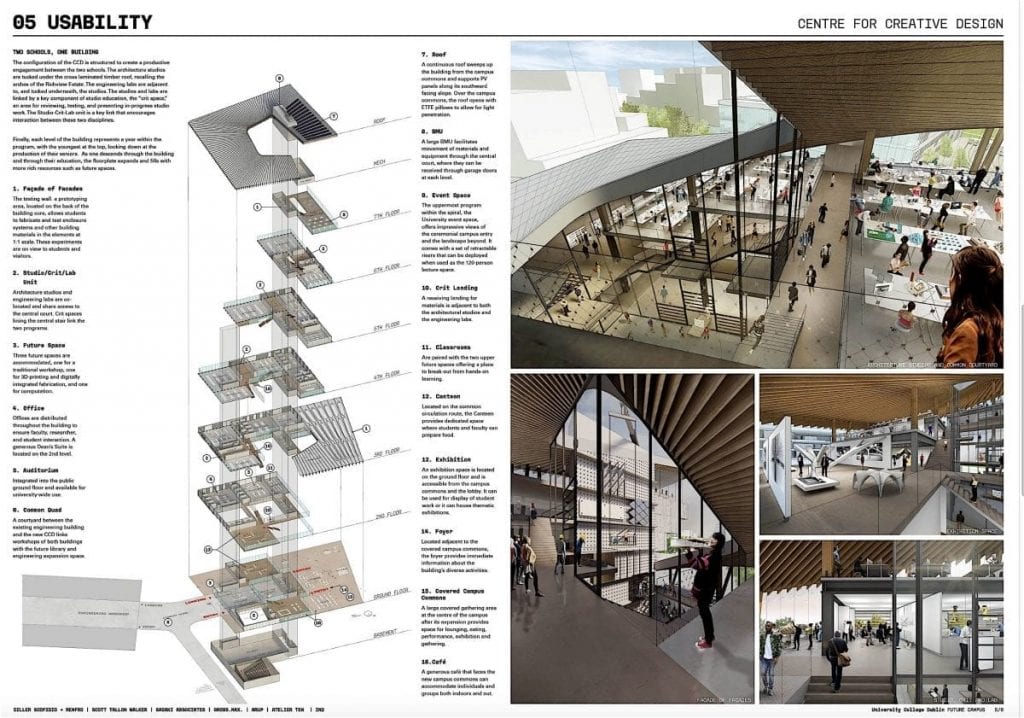

Finalist

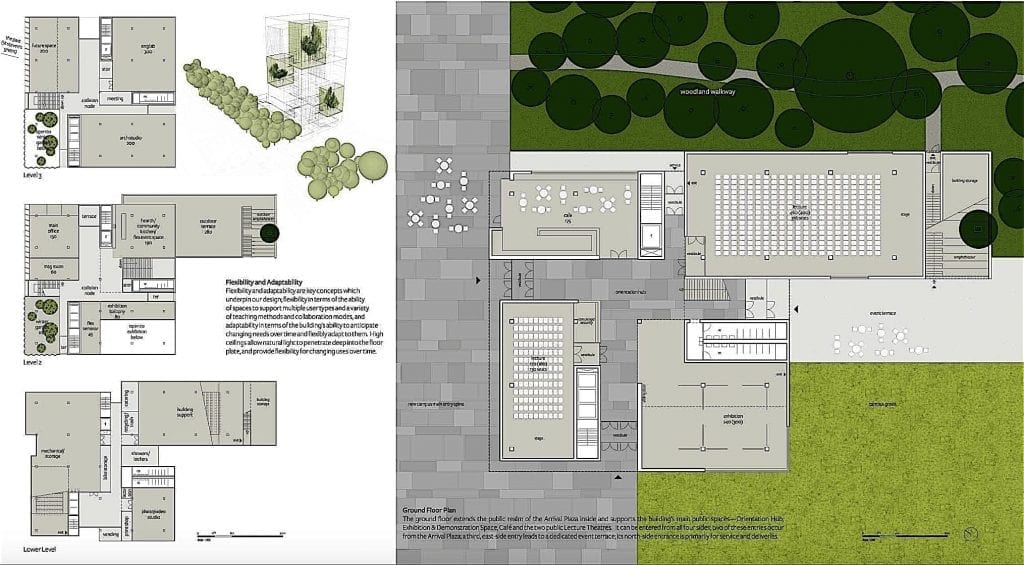

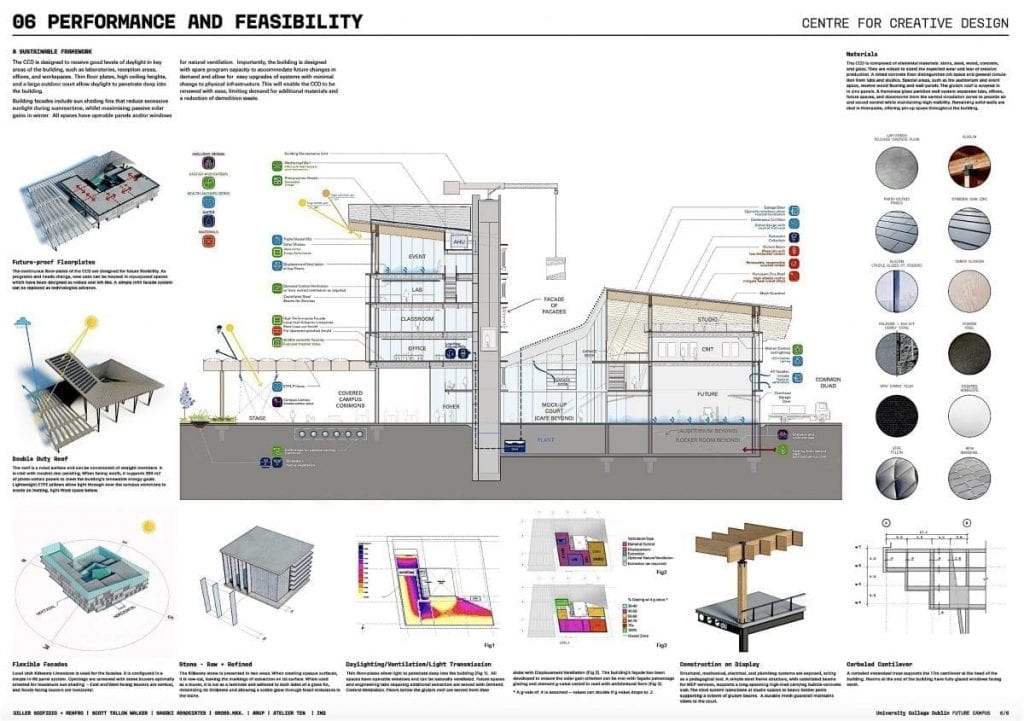

Diller Scofidio + Renfro (US) with Scott Tallon Walker Architects, Sasaki Associates, GROSS. MAX., Arup, Atelier Ten, IN2 Engineering Design Partnership, Linesight, Michael Slattery Associates and i3PT

Images: ©Diller Scofidio + Renfro / Malcolm Reading Consultants

Diller Scofidio Renfro’s CCD building resembled more of a strong ceremonial statement rather than the announcement of an arrival feature at the edge of the campus. Set back from the main entrance, it was the located centrally at the end of a plaza, flanked by buildings forming a V shape as they extended outward toward the CCD. The elevation of the buildings forming that “V” were higher facing the plaza, then diminished in height facing a park-like area in the rear. From this it was obvious that DSR wished to concentrate the expansion of campus facilities around an interior core, thus making room for more green space on campus.

The CCD is a seven-story building, with floors 3-5 allocated for architecture and engineering spaces. Because this is a high-rise, we find the paired architecture/engineering levels separated by year. While interaction between architecture and engineering is assured, contact between the various years is not encouraged. We should note here, that the renderings do show that there are open views to some areas from one level to the next, possibly ameliorating the separation resulting from the multi-floor configuration. -Ed

Finalist

John Ronan Architects (US) with RKD Architects, CLUAA, BSM Landscape, Michael Boucher Landscape Architecture, Arup, Transsolar and Pritchard Themis

All above images©John Ronan Architects

John Ronan proposed a very simple, but striking ten-story highrise as an campus arrival feature. As attractive and eco-friendly as this building was, the limitations placed on the size of the floor plates required a stacking program, limiting both interaction on the the interdisciplinary level by virtue of the common fragmentation issue. Ronan foresaw the site as a pedestrian only area, including the bridge spanning the adjoining highway. Aside from a commons area to the northeast of the main building, surrounded by university structures, the area was left open to change, essentially as future priorities might dictate. -Ed

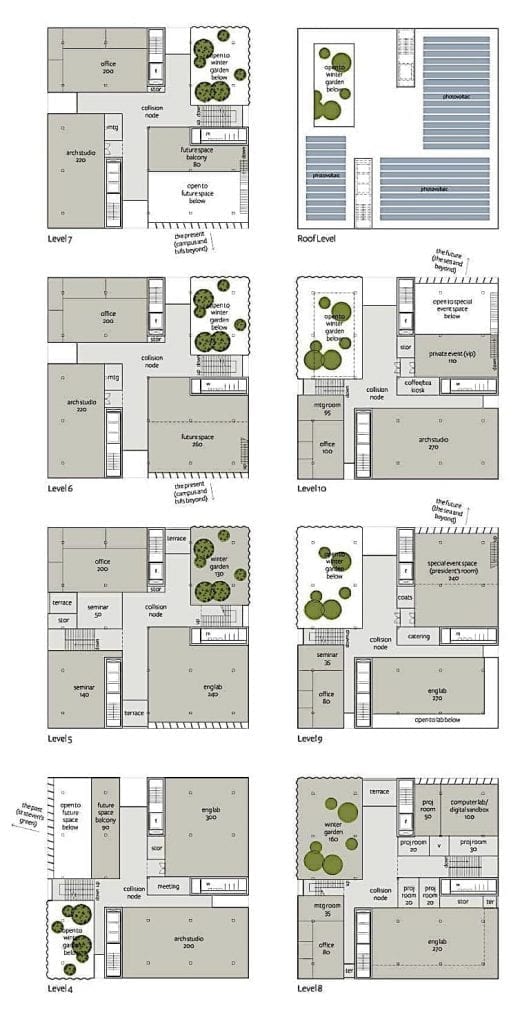

Finalist

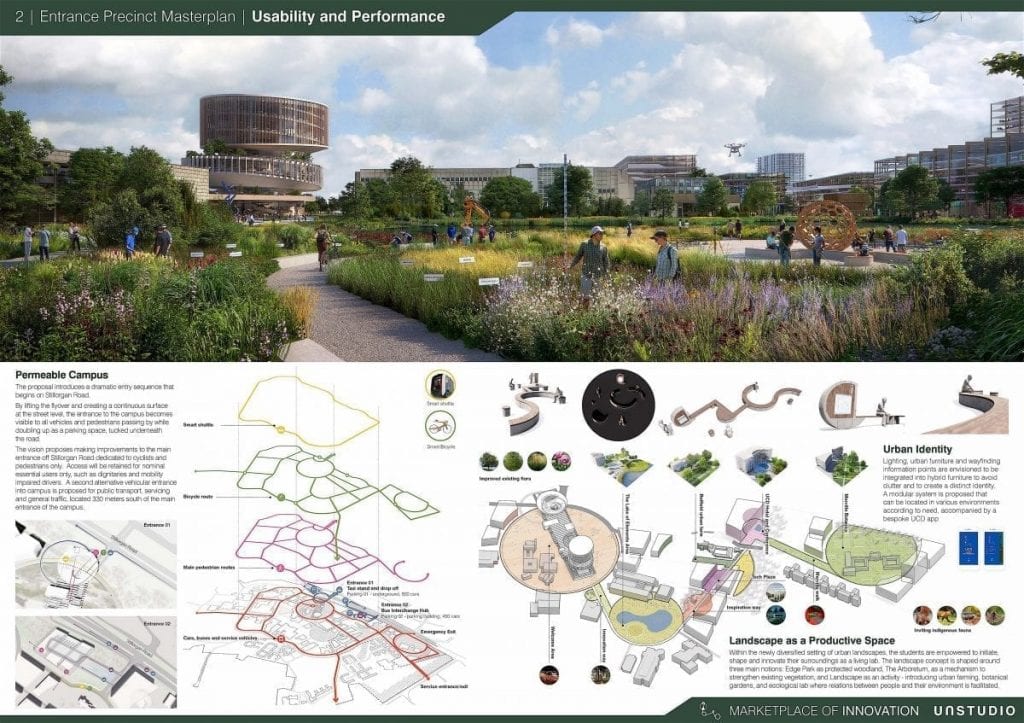

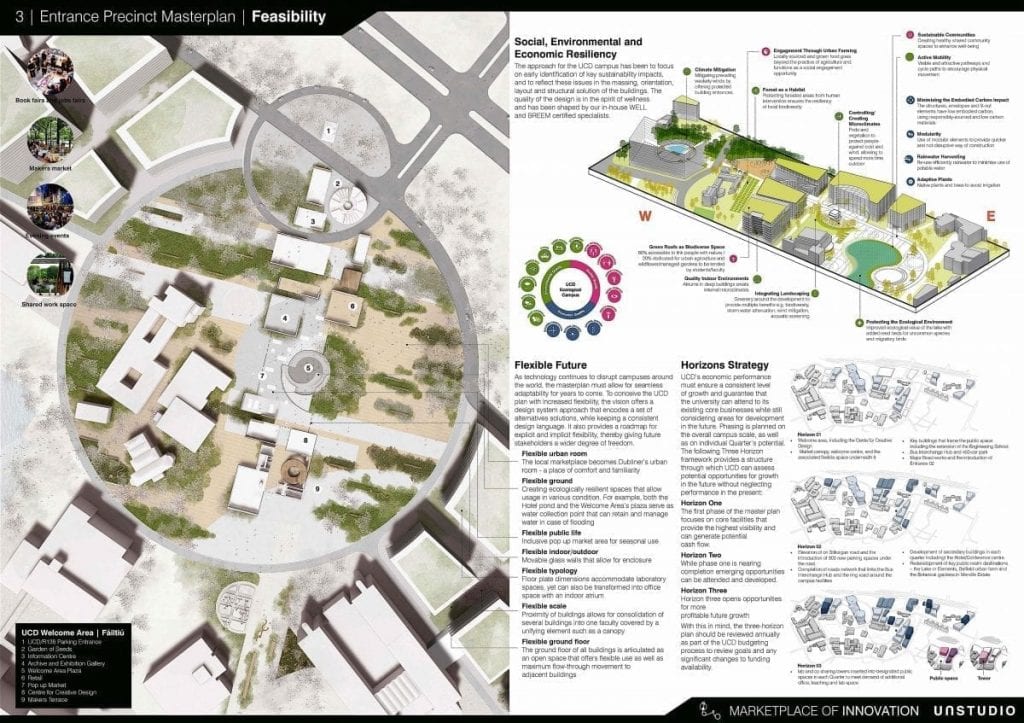

UNStudio (Netherlands) with MOLA Architecture, Arup, REDscape Landscape & Urbanism, fwdesign, Maurice Johnson & Partners and i3PT

UNStudio: Ben van Berkel, Caroline Bos with Marianthi Tatari, Dana Behrman, Clare Porter and Pedro Costa, Stella Nikolakaki, Ajay Saini, Chen Shijie, Maria Zafeiriadou

UNStudio’s proposal for the siting of its major CCD structure in some ways was similar to that of the DSR scheme in that it was located in the interior of the site. But there the similarity stopped. First of all, UNStudio’s link from the entrance to the buiding in the interior was not a plaza, but linked by a narrower axis as a generous pergola. In contrast to the other entries, UNStudio’s spine was not perpendicular to the street, but tiltled slightly. Also, UNStudio’s main structure was surrounded by a circular park-like area, separating it from the rest of the university facilities that might appear in the future. As for the building itself, it fulfilled all of the considerations that one would associate with a modern school of architecture: the open floorplate plan was ideal in that it allowed for both a high degree of interdisciplinary interaction, flexibility, and future planning. It was very much in tune with lessons learned from the New School of Architecture Aarhus competition held in 2015. The multiple use of new highrise buildings surrounding this site may have been counterproductive, in that it gave the surrounding area a more corporate, rather than academic character. Without any information concerning the ranking of the entries, one would have to assume that this one was a serious contender at the top of the list. -Ed

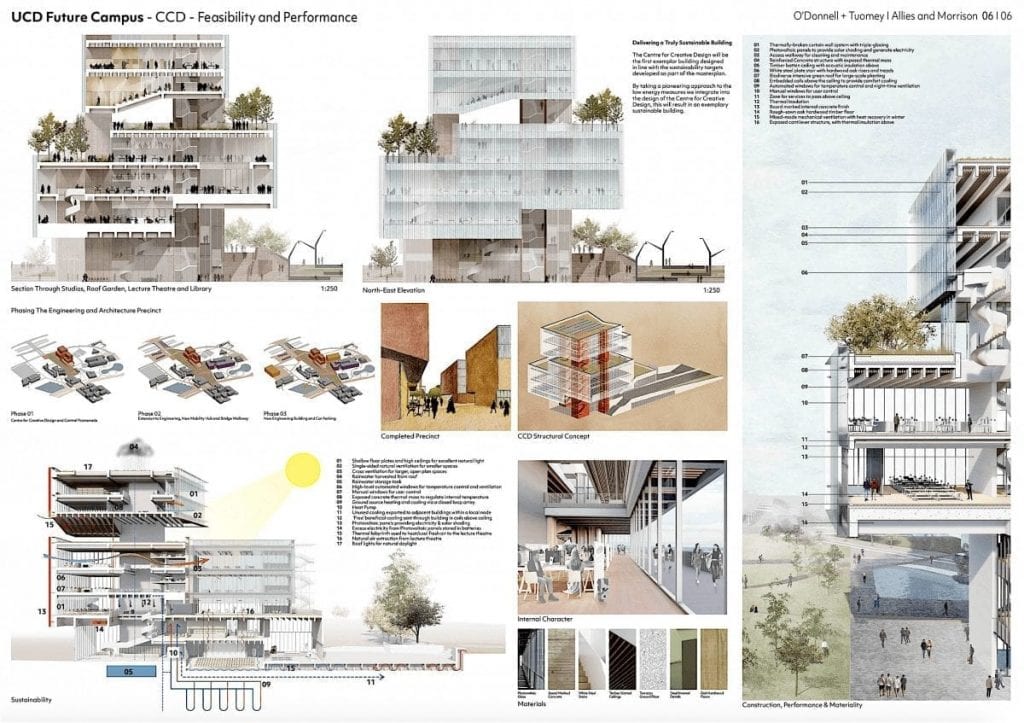

Finalist

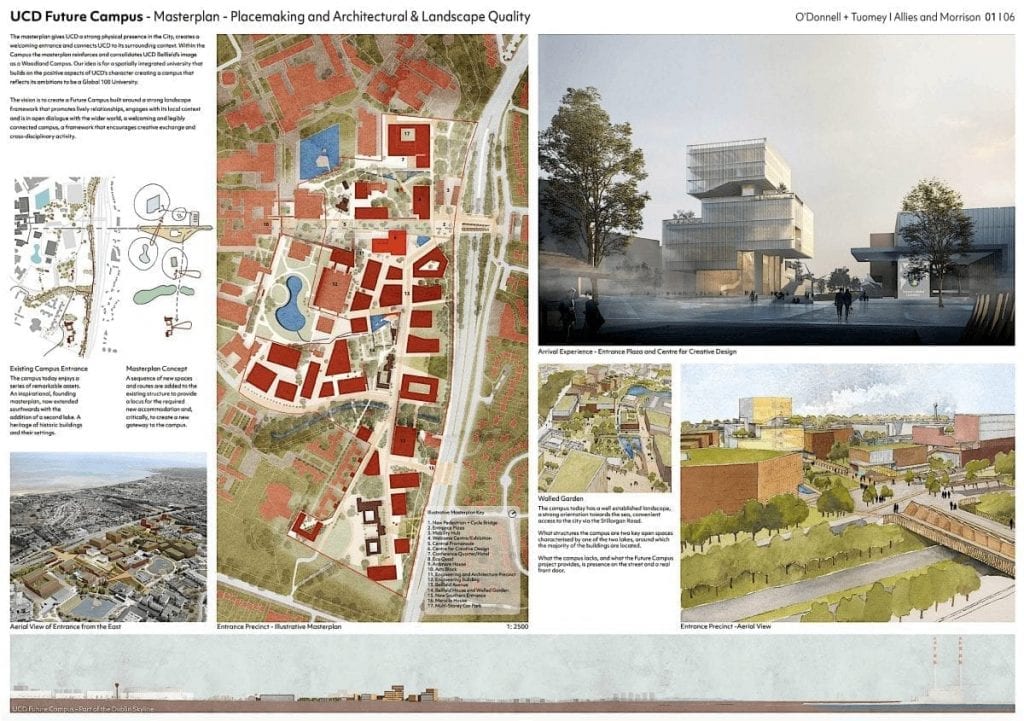

O’Donnell + Tuomey (Ireland) with Allies and Morrison, Arup, Hargreaves Associates, Superposition, Plattenbau Studio, Phil Jones Associates, Max Fordham, MLM Group, Dermot Foley Landscape Architects and Horganlynch

Images: ©O’Donnell + Tuomey/Malcolm Reading Consultants

O’Donnell + Tuomey’s CCD building might not be the first thing you would see unti you were at the entrance to the campus immediately exiting the bridge. When it does come into view, one can be sure that it is not some corporate structure; based on its sculptural form, there is an obvious connection to design. Although the authors state that the “open floorplates” are conducive to an interdisciplinary atmosphere, the design of those three almost identical stories would appear to be rather static, not quite having the flexibility the authors would like us to believe. The roof garden is a terrific idea at mid-level, and the renderings depicting the various areas of the building certainly portray a welcoming atmosphere. -Ed

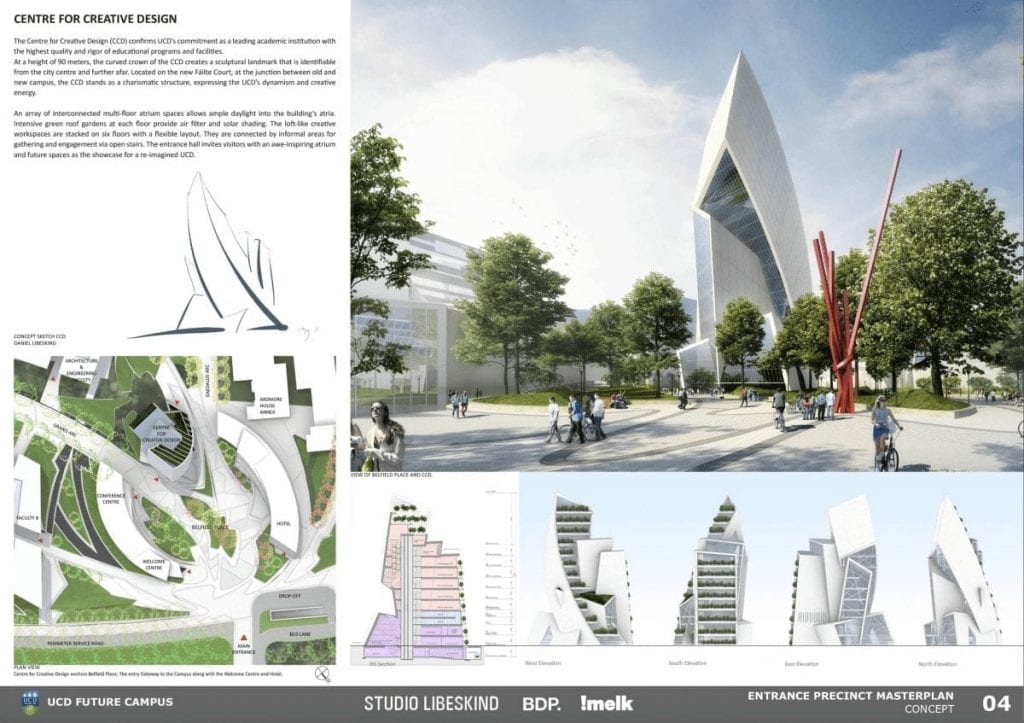

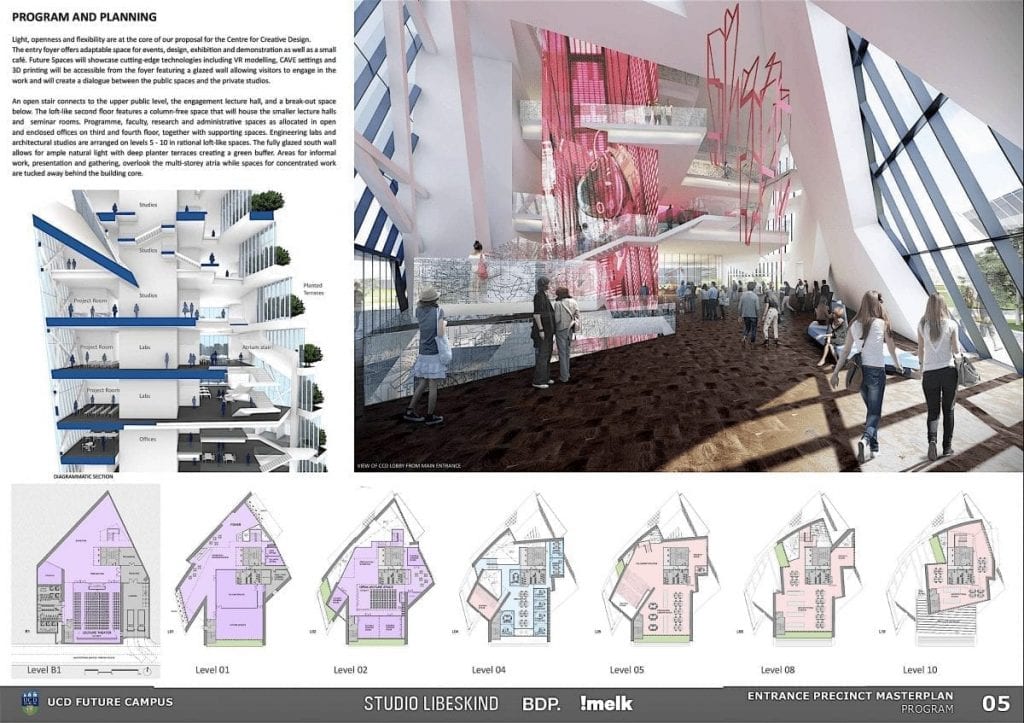

Finalist

Studio Libeskind (US) with BDP, !melk, NRB, Dcon, Arup, Brock McClure Consultants, O’Herlihy Access Consultancy, JGA and i3PT

Images: Studio Libeskind / Malcolm Reading Consultants

Studio Libeskind’s sculptural proposal for the CCD had much in common visually with the firm’s design for the “Crown” in Casalgrande Padana, Italy, albiet on a much larger scale. This was certainly an iconic form that could be seen from various parts of the campus—a real landmark. As for imagery, this building would seem to have more in common with a religious edifice, with the most remote suggestion that it had something to do other than with metaphysics. But by using this formula, the designers put themselves in a straitjacket when it came to satisfying the program organizationally. Cramming a difficult program as demanded here into such a structure would appear to negate any idea of the intended interdisciplinary principle. This is another case of designing from the outside in. -Ed