Young Architects win a Restricted Competition

over High-Profile Competitors

“Today the majority of design competitions are exclusively based on prequalification, which means that only established companies that have participated in numerous building projects qualify. The competition format that was chosen for this project challenged this, and the result shows that it was entirely successful.”

– Norwegian Architect Reiulf Ramstad, who together with Architect Jens Thomas Arnfred, acted as design professionals in both the Open Design Stage and the subsequent Restricted Design Competition with three from the open stage competing.

After surmounting two formidable obstacles, an open international competition with over 260 entries and a second stage limited to four other finalists—two of which were high-profile invitees*—the young Copenhagen firm of Vargo, Nielsen & Palle was declared the winner of the Aarhus School of Architecture Competition. As is often the case when a competitor from a small firm advances to a final stage, the winner teamed up with ADEPT, which had placed in the top six as an honorable mention in the open stage and Rolvung & Brøndsted Arkitekter, Tri-consult and Steensen Varming.

The Design Challenge

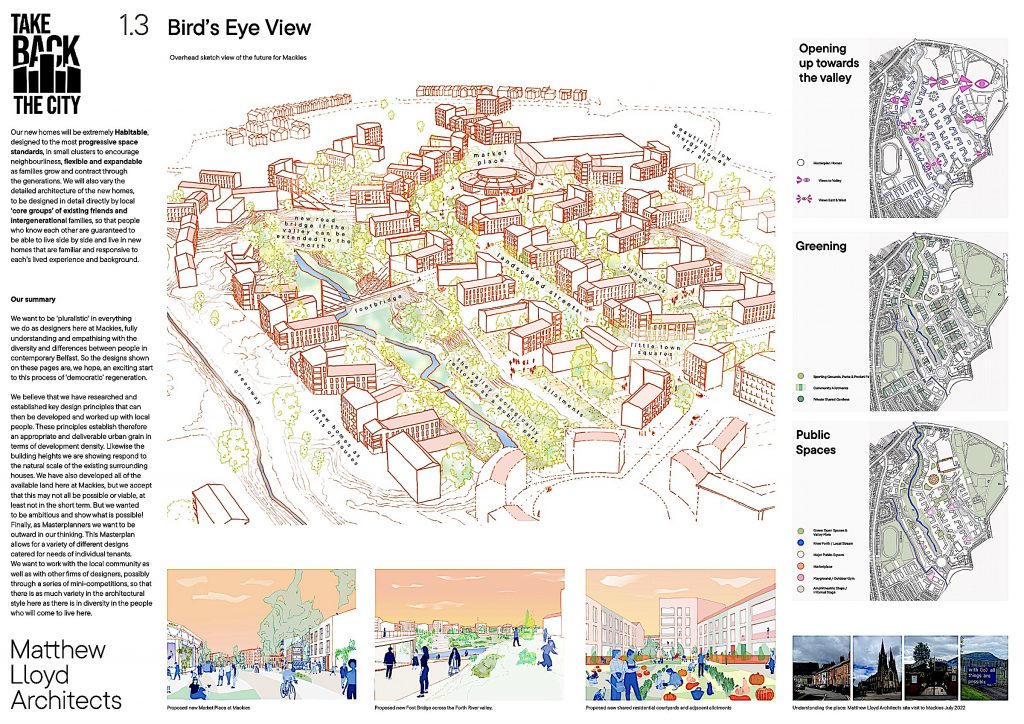

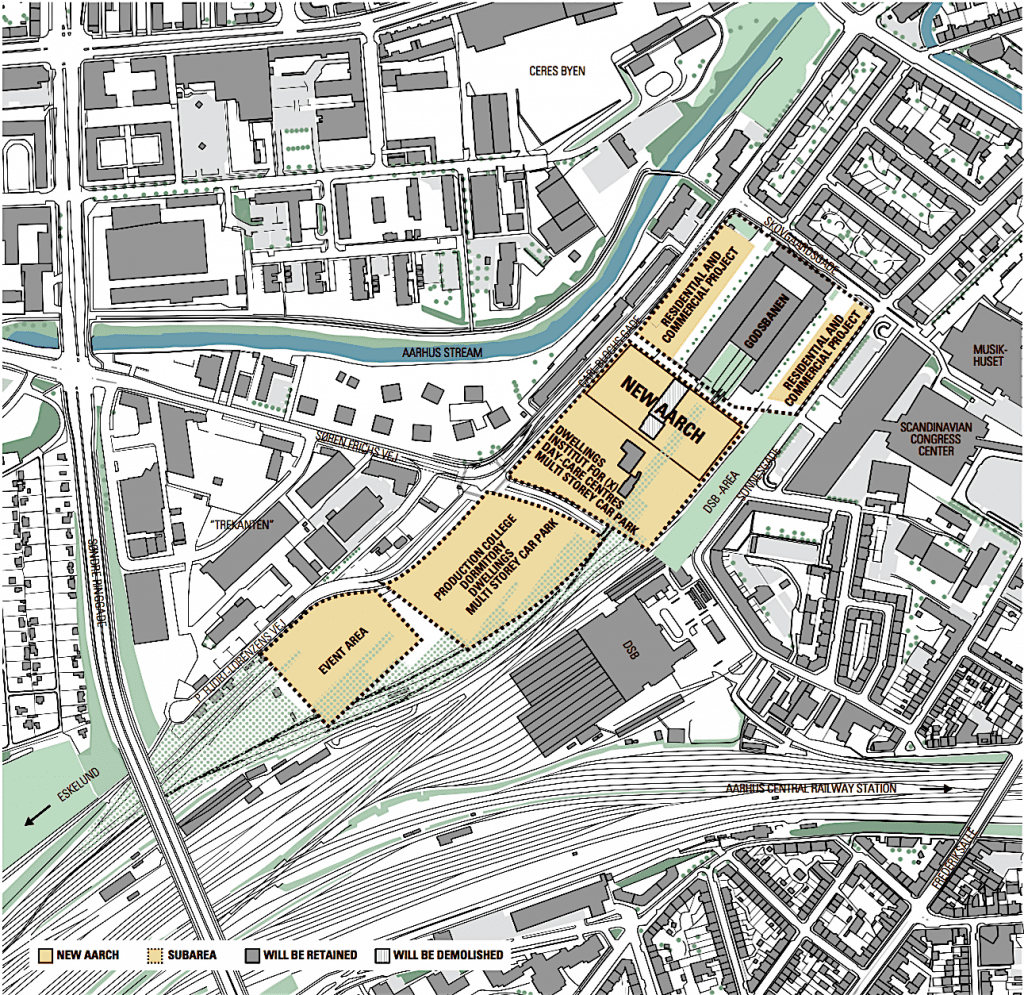

The site for the competition was an abandoned railyard near the Aarhus city center. As is true of a typical railroad location, the site in its entirety is linear, with a slight bulge in the center. And it is in this central location of the site, perpendicular to the tracks, that the new school of architecture is to be built.

As the first new school of architecture to be built in Denmark, the Aarhus school is to focus equally on practice as well as the visual theory. The competition brief is clear in its statement of the client’s aims:

“It’s about imagining a completely novel way of organizing a school of architecture, about providing the optimal physical framework for learning in an environment characterized by openness, community and knowledge sharing—in a physical space of high architectural quality.”

Other priorities are the use of light, where during the winter months is at a premium, and sustainability.

For a building of this magnitude, especially in a small country where architects are held in such high regard, the building budget can only be described as modest. A total of $42M, of which $25M is for building construction, pales in comparison to the sums provided for recent new architecture school buildings elsewhere (The recent Kent State School of Architecture cost $42M). This had to be in the back of the minds of the jurors as they examined the 260 entries in the open competition. In the end, there was an open admission that money was a factor:

Competition Site in an abandoned railyard

“The framework and economy of the new school of architecture are modest, which has forced the school and us to think hard and give priority to the right aspects from the very start. The initial open design competition enabled us to draw up a competition brief that has helped us find a robust winning project – a project in which the concept and the idea have been reduced to the bare essentials.

“We have been fortunate enough to find a winning team which has very skillfully – but also in a subdued and humble way – read, understood and solved the task. Architecture, functionality, and economy have been interconnected criteria during the assessment, and we are pleased to have a winning team which has understood the spirit of the budget without allowing inventiveness to suffer in consequence. This has convinced us that they are fully capable of handling the task and realizing the project.” -Signe Primdal, Jury Chair

So the end result of many of the design proposals was what could easily be regarded as a giant shed, almost factory-like. But this was hardly in conflict with the competition program, which suggested that the practice of creating by using materials was just as important as the drawing board. Therefore, it could hardly come as a surprise that the top three premiated designs in the initial, open stage had that industrial look. Instead of accommodating locomotives, this new building complex was there to encourage the creativity of young architecture students.

A former student at the Ball State University’s College of Architecture and Planning once was heard to reflect back on the initial years of the school, when it was located in Quonset huts: ‘When we moved from the huts into the new building, we lost something, the simplicity of a design environment.’ Maybe the Danes have latched onto something here!

The results of this competition is yet another example dispelling the notion that young architects are incapable of recognizing and dealing with the issues surrounding a low budget, difficult site product with high expectations.

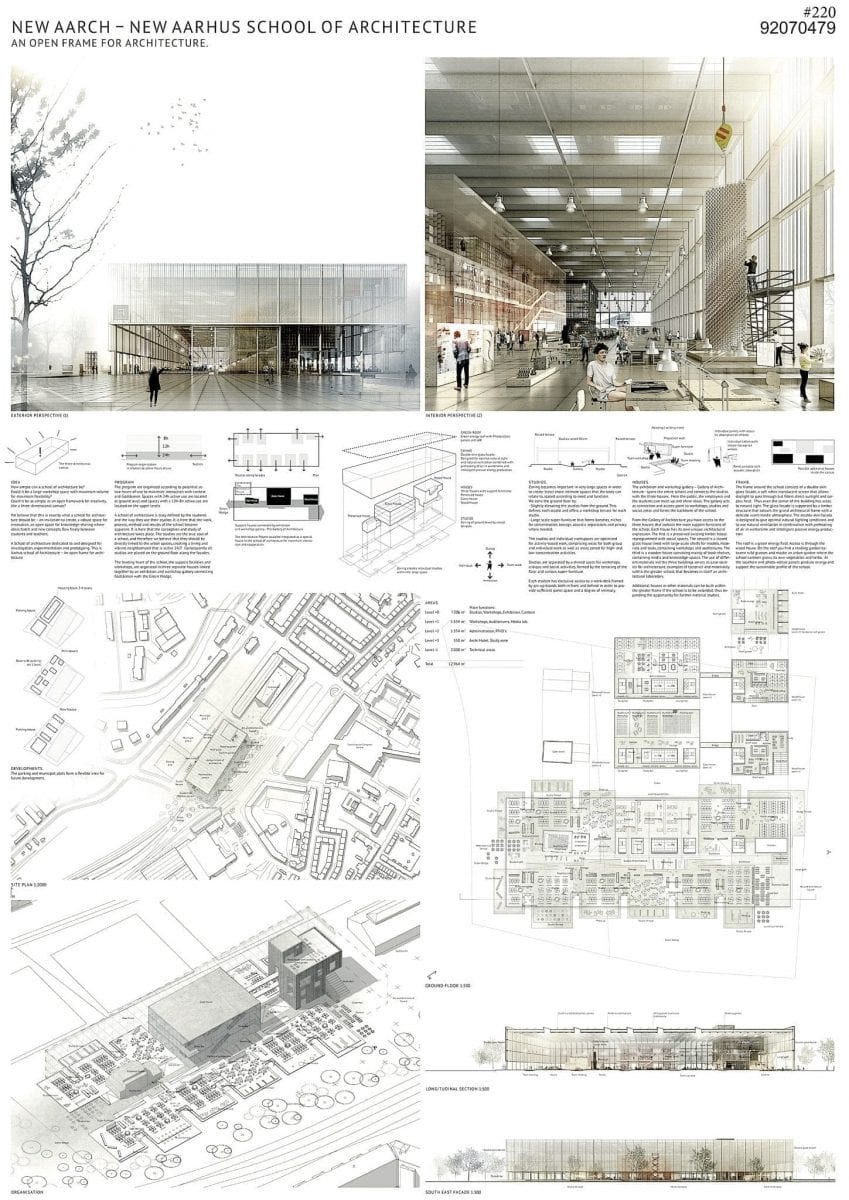

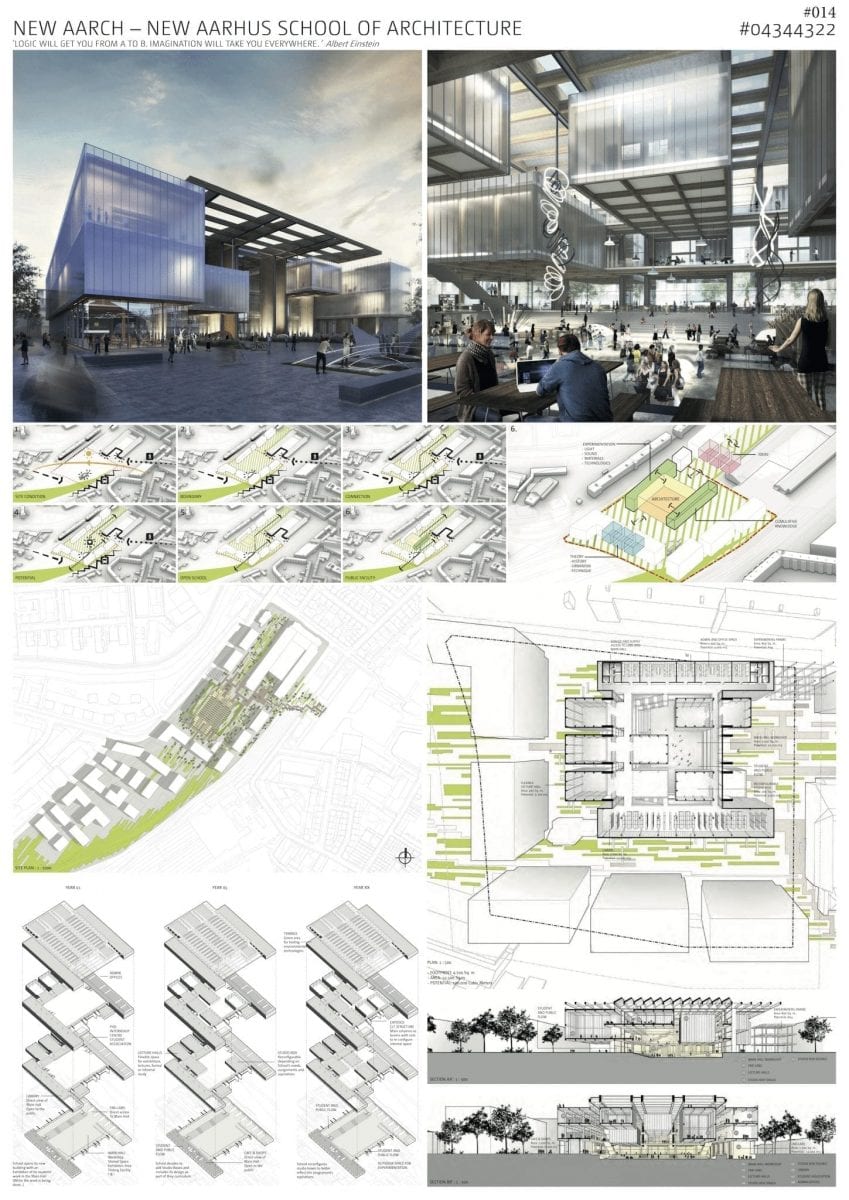

Winner

Vargo, Nielsen & Palle, Copenhagen

with ADEPT, Rolvung & Brøndsted Arkitekter, Tri-Consult and Steensen Varming

2nd stage images ©Vargo, Nielsen & Palle/ADEPT

1st stage board ©Vargo Nielsen & Palle

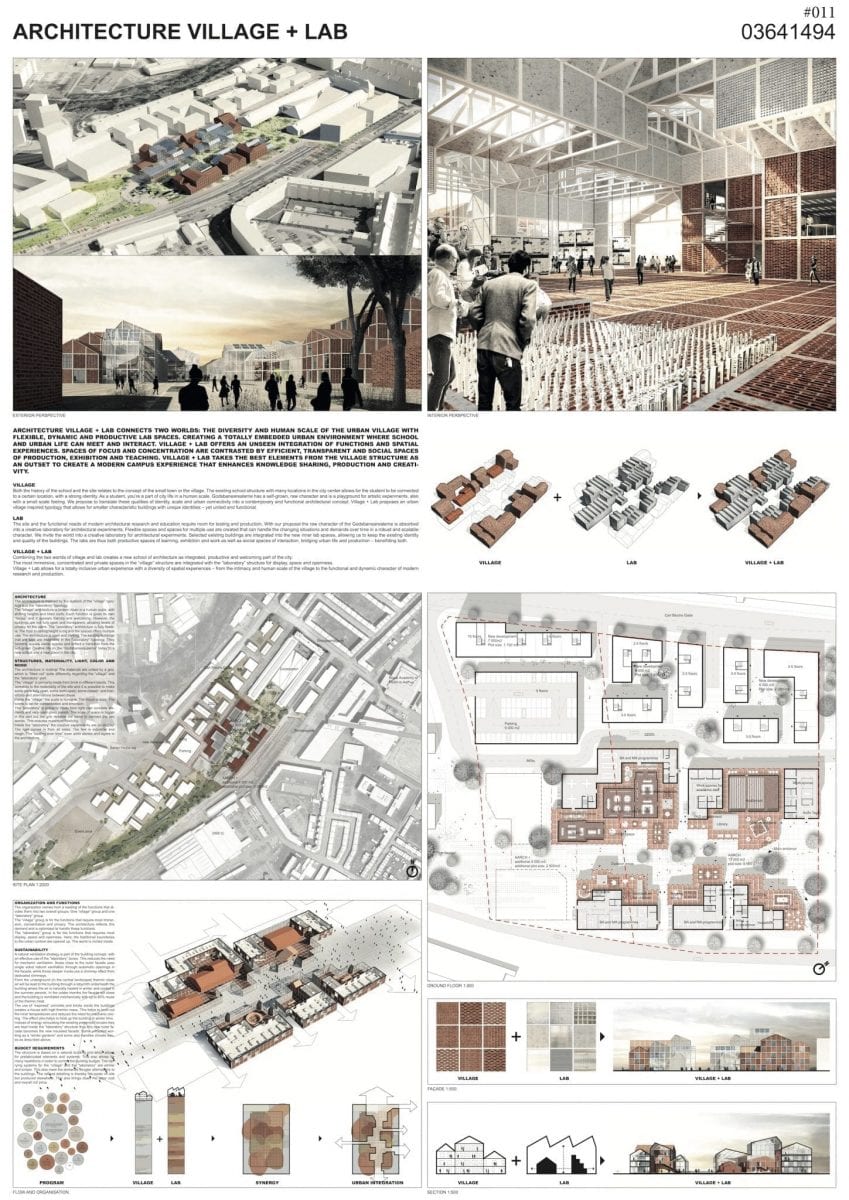

Second Stage Finalist from open competition

Erik Giudice Architects, Sweden/France

with Niras and Kragh & Berglund

1st stage board © Erik Giudice Architects

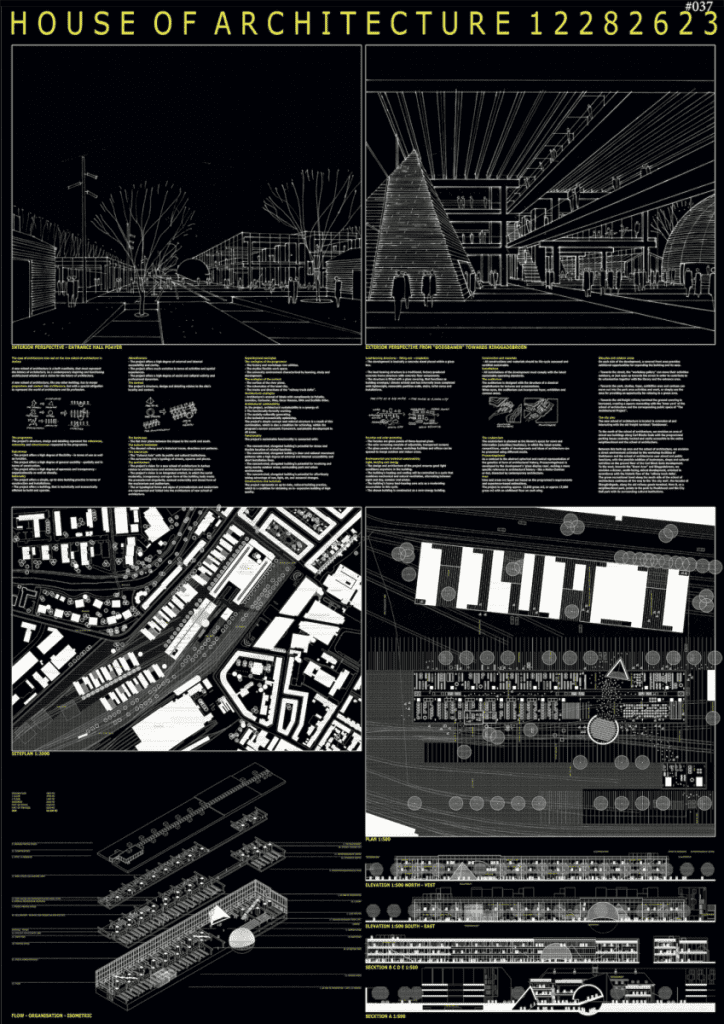

Second Stage Finalist from open competition

Atelier Lorentzen Langkilde, Copenhagen

with Buro Hapold

Image: ©Atelier Lorentzen Langkilde

1st Stage purchase

ADEPT, Copenhagen

1st Stage purchase

Bogle Architects, U.K.

Competition board ©Bogle Architects

1st Stage purchase

JWH + Vesthardt Arkitekter, Aarhus

Competition board ©JWH + Vesthardt Arkitekter

2nd Stage preselected invitees (not shown)

BIG, Bjarke Ingalls Group, Copenhagen

Lacaton & Vassal / Bessards’ Studio, Paris, France

* SANAA (Japan) in collaboration with B+G Ingenieure, Sasaki & Partners and Transplan (pre-qualified, but chose not to submit a project without further explanation)