by William Morgan

Winning entry ©D/R/E/A/M Collaborative / Wozny Barbar & Associates

“We must look beyond current options and activate new and original ideas,” declared Mayor Martin J. Walsh in announcing Boston’s first-ever housing competition. “The Housing Innovation Competition, “ Walsh continued, “ is a chance for Boston to take its place in the forefront of housing innovation.” Announced in 2016, less than a year after the creation of the Mayor’s Housing Innovation Lab, the competition was to address the steep costs of living in The Hub, the lack of affordable housing, and the resultant strains on residents and new arrivals. iLab joined the Department of Neighborhood Development, the Garrison Trotter Neighborhood Association, and the Boston Society of Architects in soliciting affordable housing schemes for three city-owned lots in the Roxbury section of town.

As Tamara Roy, president of the BSA, said, this was “not an ideas competition–you had to have a developer willing to build workforce housing units with all the restrictions that city-owned land has. And the lots were small.” Marcy Ostberg, director of iLab noted, “We asked development teams to propose innovative compact designs.” The goal of the competition was “to show that small, affordable family units are feasible.” Living units smaller than what the city codes allow might create more opportunities for renting and ownership; plus, more diminutive housing might find spaces closer to downtown. “Through this competition,” Ostberg declared, “we wanted to find out the potential for creating these units.”

Even though the aims of the competition were positive–“to stimulate the architect, contractor and developer communities to collaborate on the creation of lower-cost prototype dwellings” (according to Boston’s Chief of Housing, Sheila A. Dillon), the level of participation was disappointing. There were more jurors–nine–from the city, neighborhood, design and building professions than submissions–seven, and one of those failed to meet the requirements.* The jury was asked to consider innovation, design, sustainability, and affordability, but the emphasis on relying less on design expertise and more on community involvement may account for low number of competitors. But it is especially surprising given that the winning project is scheduled to begin construction this year, with the possibility of employing the scheme as a template for further construction in other neighborhoods.

Nevertheless, the six finalists for the Housing Innovation contest demonstrated a certain level of success. Among the half dozen designs, there were a wide variety of styles, construction methods and materials, and even unconventional financial proposals. Clearly, competitions are now seen as a significant tool for the development of affordable housing in Boston. Competitions are understood as a way to test new ideas, and that well designed, compact flexible spaces could be an integral part of the residential landscape in the inner city.

Winning Design

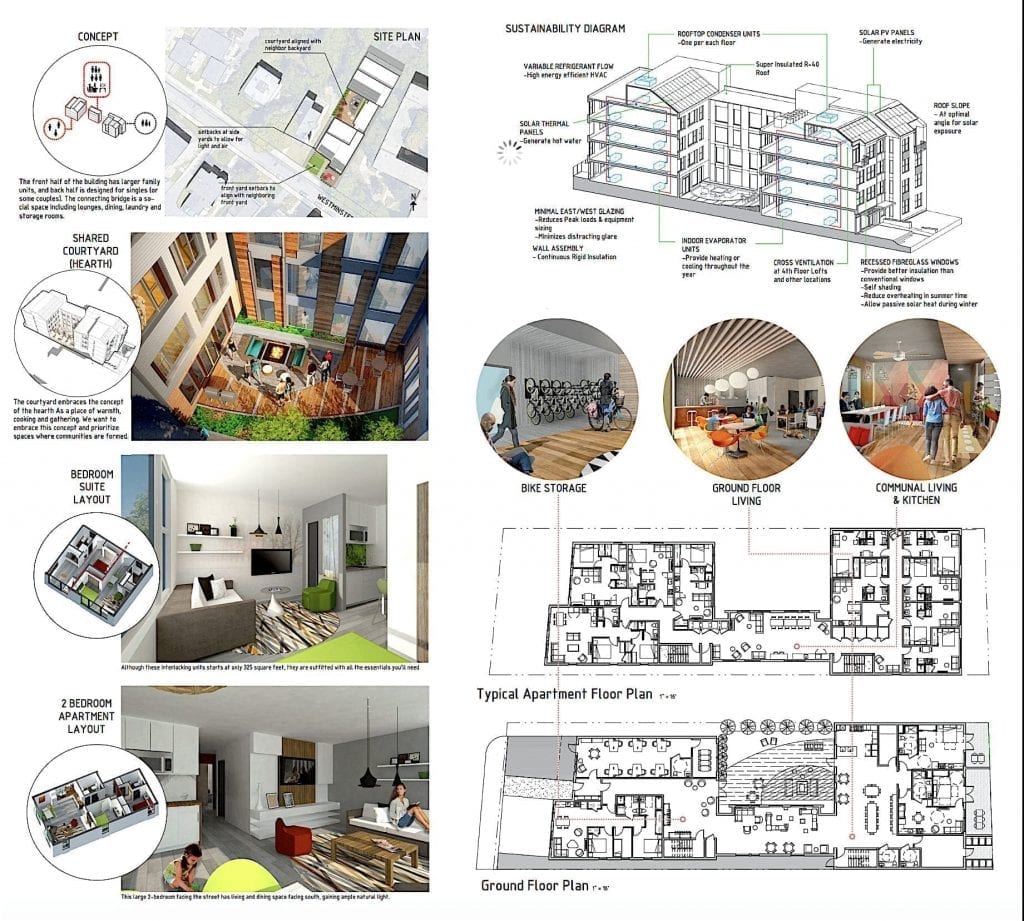

D/R/E/A/M Collaborative / Wozny Barbar & Associates

Dream Development, the winning design by D/R/E/A/M Collaborative, along with Wozny Barbar & Associates, features twelve living units, comprised of studios, one-, two-, and three-bedroom units, ranging from 436 to 955 square feet. The two-and three-bedroom units occupy two stories, with windows on both sides of the block; these units can be combined with the studios below to support multi-generational living. The twelve apartments all have outside addresses, although shared entries create five outdoor stoops. Six parking spaces are hidden behind the building. The three-story passive solar block has photovoltaic panels and storm water collectors. Community lawn space is in both the front and back of the project.

Images: ©D/R/E/A/M Collaborative / Wozny Barbar & Associates

Finalist

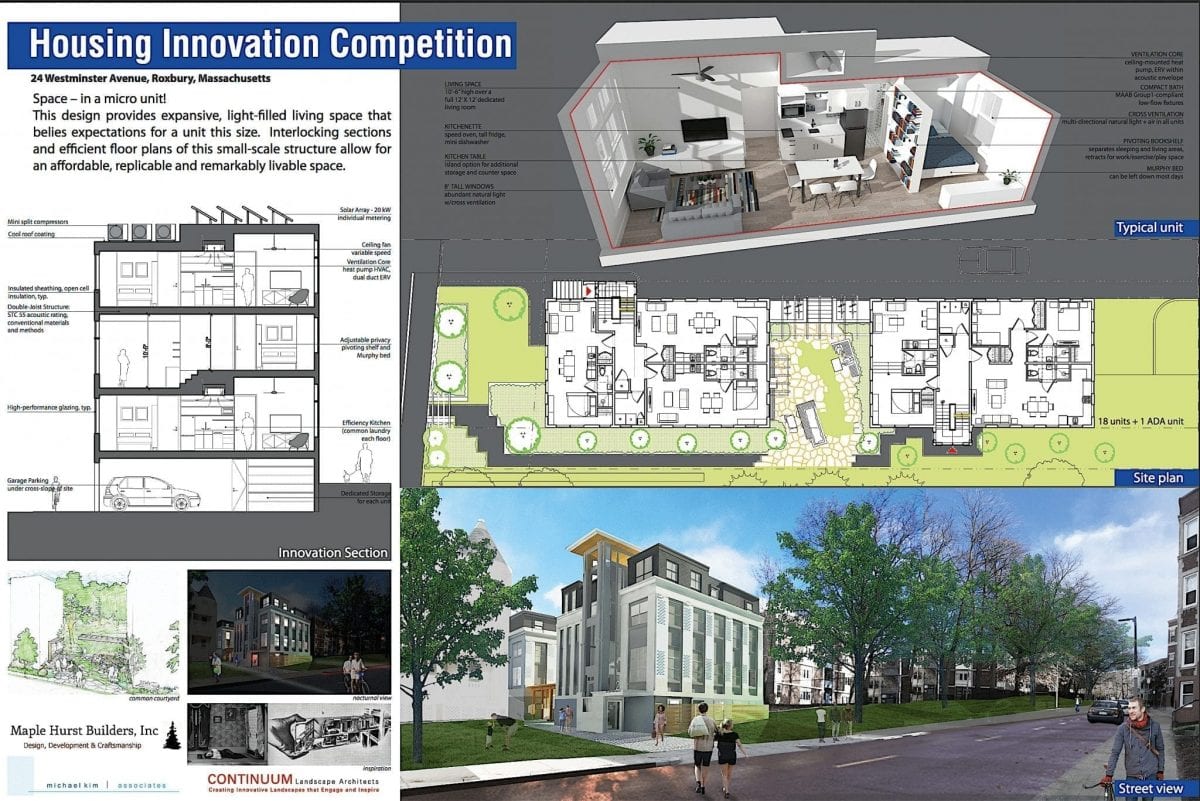

Michael Kim / Maple Hurst Builders (Unconventional Excellence Award)

There were three sites available, but the Maple Hurst design of Michael Kim and Maple Hurst Builders is at the same location as the winner. Not surprisingly, as with most the designs for public structures nowadays, a lot of attention is devoted to sustainability, with a solar array, heat pumps, high-performing glazing, and so on. The program is three stories, with a bermed basement to allow covered and hidden parking. Through very clever juggling of ceiling heights and flexible plans, the Maple Hurst team fit in nineteen flats (including one ADA unit). The change in materials between the monumental first two stories and the third story, along with a four-story stair tower, gives the exterior appearance a commercial mien. Yet, a considerably large and attractive common courtyard by Continuum Landscape Architects is situated between the two halves of the building.

Images: ©Michael Kim / Maple Hurst Builders

Finalist

Hearth House (Innovation Excellence Award)

Corcoran Jennison Associates / WHAT’S IN

Far more visually attractive is the Hearth House proposal, which also chose the same site as Dreamworks and Maple Hurst. And like the latter, it is composed of two large blocks separated by a common courtyard, although here there is an actual hearth as an eponymous focal point. While the number of units is not specified, these range from “a single working class tenant to a three-person family.” The clever spacing-saving interlocking jigsaw puzzle-shaped plans are reminiscent of Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation. As the Hearth House team noted, “choosing to live in a relatively smaller space should not mean sacrificing living large.” While taller than the other schemes, Hearth House employs clapboard like façade (some sort of concrete board, presumably) that pays tribute to the late19th-century shingled house next to it.

Images: ©Corcoran Jennison Associates / WHAT’S IN

Finalist

Urbanica (Design Excellence Award)

The long narrow sites lend themselves to the split block idea and a central communal courtyard. But that similar template then offers a lesson in how different designers and builders approach the same design challenge posed by such restricted spaces. Urbanica refers to their “multivalent” concept of their UHomes, of two blocks, one with three “Starter Loft concepts,” the other with six “Multi-Generational Townhouses.” With its shed roofs, porches, and gray-shingled walls, the Urbanica project seems the most traditional, yet there are no faux Georgian, New Urbanism cues. It also the handsomest, and did garner the competition’s Design Excellence Award. Since it can be assumed that all the projects will be up-to-date in terms of energy-saving systems, there is something to be gained by presenting a visually attractive package.

Finalist

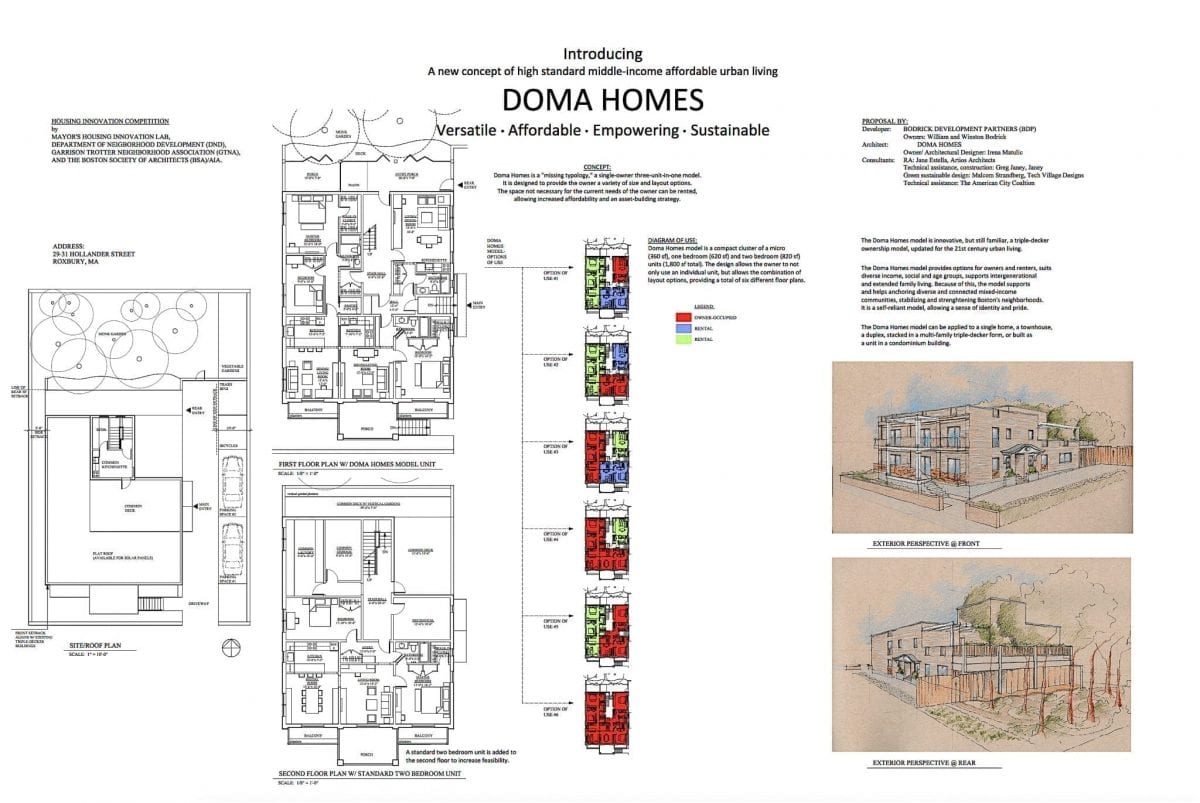

Doma Homes (Unconventional Excellence Award)

Architect Irena Matulic, along with Bodrick Development Partners, proffered a flat-roofed, two-story, single unit complex. Doma Homes has perhaps the most flexible plan of all, showing six combinations of layouts put together with units ranging from micro (360 square feet) to one and two-bedroom units (820 square feet), everything from single home townhouse” to a “duplex stacked in triple-decker form. “ The building, which features a common roof deck and a large, treed garden at the rear, could be developed as rentals or condominiums. For all its flexibility, the Doma project is the least visually appealing (the exact nature of external sheathing is hard to make out from the renderings), with a curious main entrance porch that mimics a suburban colonial pediment–a Post-Modern tribute to Michael Graves, or perhaps a nod to the supposed lower-class aesthetics of the neighborhood?

Finalist

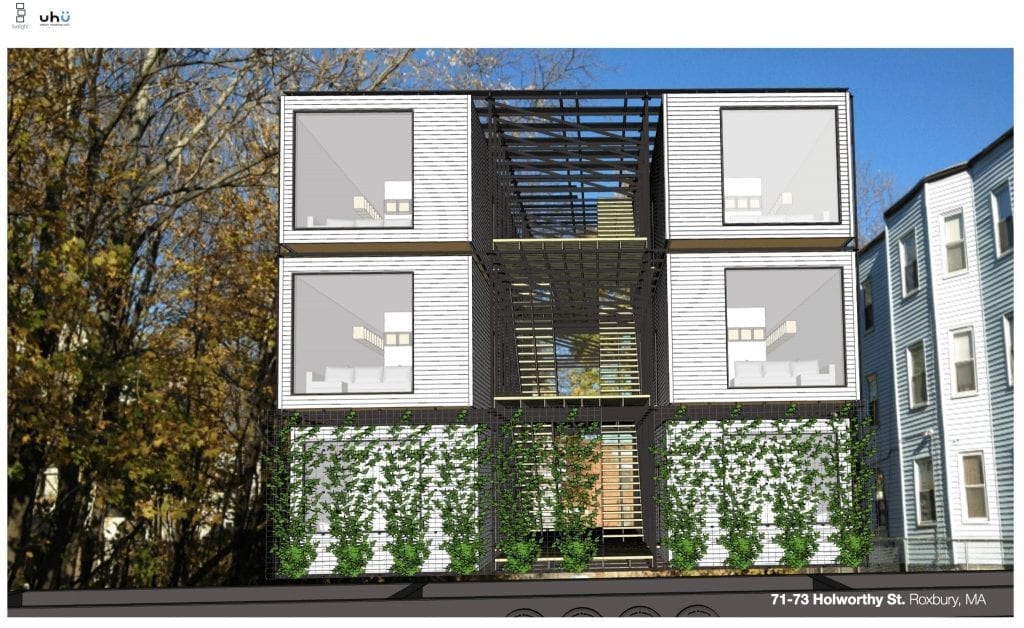

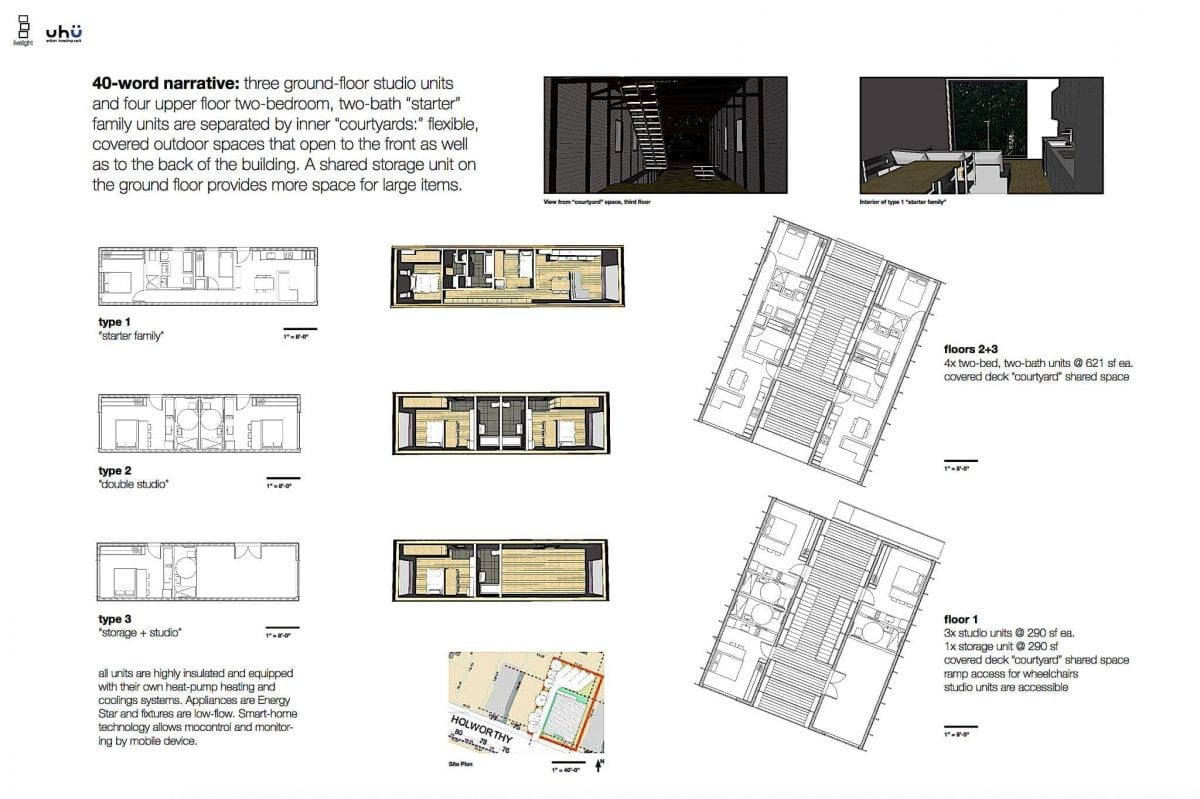

Livelight (Sustainability Excellence Award)

Livelight, was the design with the most potential. Based on the concept called Urban Housing Unit, a modular approach that would, in Unité or Montreal Habitat fashion, insert prefabricated units into slots in a superstructure. The basic building block, or Uhü, should be familiar to Bostonians, as a one-bedroom model traveled for three months to a variety of city neighborhoods and was visited by several thousand residents (the competition’s press release featured a photograph of the interior of the Uhü). Livelight offered three ground-floor studios and four upper-floor, two-bedroom, two bathroom starter units. These are clustered in three stories flanking a covered inner courtyard that runs the length of the structure; there are also covered outdoors spaces at both the front and rear of the complex. Given an acceptance of prefabrication, the Uhü method offers what the designers call “a paradigm-shifting model for Boston and residential construction around the world.” Yet, except for the lowest-end manufactured housing, Americans resist prefabrication; Livelight’s chief designer, Addison Godine, was informed by a neighborhood juror that they “would never agree to micro units.” Did the Uhü design perhaps seemed too Modern, even too European, for public housing in Boston’s Roxbury?

But stylistic considerations aside, the Housing Innovation Competition was a success in demonstrating that small, affordable family units are feasible–as long as they look like traditional types of homes. For better or worse, from now on, innovative housing for Boston will be community based, and about more the needs of those who will occupy it than architectural design. Construction of the winning Dream Work housing will offer additional revelations, but perhaps what was most innovative was the holding of the competition itself.

*It should be noted that the requirement for designers to match up with a developer would have depressed the number of teams willing to participate from the start, as one usually can only find a limited number of developers willing to participate in a competition. Had an open, initial design stage taken place without a developer, then provided the winner(s) with an option to choose one, the interest on the part of designers would undoubtedly have been greater.