This essay was first published in The Architectural Competition – Research Inquiries and Experiences, Magnus Rönn, Reza Kazemian, Jonas E. Andersson (Eds.) Axl Books Stockholm, 2010 (pp. 578-600)

View from Memorial to Washington Monument

Introduction

The Vietnam War, 1959-75, was the longest and most divisive in American experience. 58,000 American soldiers died, 140,000 were wounded. Vietnamese casualties were far higher. The war caused permanent transformations in American society and culture. In 1979 Jan Scruggs, a Vietnam veteran, conceived the idea of a memorial to the memory of the American dead and, by implication, the veterans who had served. His further hope was that the memorial would reconcile the war’s veterans with the many Americans who had opposed the war. The memorial was to be sited in a place of honor on the Mall in Washington DC. It was to be privately funded as a citizen initiative, the federal government contributing the site. To undertake this effort a sponsor organization was created, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund (VVMF), its board members including West Point and Naval Academy graduates. Legislation to authorize a memorial, guided by Senators Charles McC. Mathias Jr. and John W. Warner, was passed by the U.S. Congress in May 1980 and signed into law by President Jimmy Carter in July. All public design projects in Washington are subject to intensive scrutiny, especially memorials. Three federal agencies, responsible for approving the design in all its aspects, were closely involved throughout the effort. Discussions concerning a design competition for the memorial had begun in May. Competition planning began in July. The formal competition process was concluded ten months later, in May 1981. The 1,432 designs submitted in the competition, a then record number, were judged by an eight-person jury, all professionals representing the principal design disciplines. The competition was won by a 21-year-old student at Yale University, Maya Ying Lin. The memorial was built and dedicated in November 1982, with a statue group and flagpole addition dedicated in November 1984, the latter the result of sometimes bitter controversy regarding the basic Lin design. The memorial became and remains one of the most visited in the U.S., having become a virtual icon. Much has been written about the design and the designer, and much attention was given to the controversy. Little has been written about the competition process itself, a process based on the highest standards for conducting design competitions. This paper focuses on that process, its context and its conduct.

Personal Perspective

My experience with competitions began in architectural school, where they are integral to the architectural design studio. Following school, studying and working in Italy and Sweden, 1954-56, my interest grew. In Italy

I also became interested in contemporary memorials due to two examples related to WW II, both the products of competitions – the Ardeatine Caves near Rome and the Monument to the Deported in Milan. In Scandinavia that interest was broadened through studying the work of Gunnar Asplund, Sven Markelius, Alvar Aalto, and Arne Jacobsen – much of their work also the product of design competitions.

In 1955, on a visit to Sweden, I saw an exhibit of the competition entries for a proposed government center for Gothenburg. The winning entry was the work of Alvar Aalto. I was impressed by the simplicity and directness of Aalto’s drawings. His design, in my view among his most brilliant, was code named “Curia” in reference to a building in the Roman Forum. His submission was drawn in pencil on ordinary tracing paper. It included perhaps two or three constructed perspectives and photos of a massing model. The rest of his presentation consisted of plans, elevations and sections. Although this project was never realized the memory of the exhibit and the directness of Aalto’s drawings served as a guide in competitions that I later managed.

This general interest developed into the gradual realization that frequent and well-managed design competitions are a vital source for advancing creative design ideas. They are its exploratory test grounds. As important, they heighten the public’s interest and elevate public expectations of design, thereby establishing a vital environment for nurturing architectural creativity.

From 1966-70 I served as the first Director of Architecture and Design Programs at the then newly established National Endowment for the Arts, an opportunity that I used to try to promote their improvement and wider use in the U.S. In doing so I undertook an extensive study of competitions, historical and recent. I solicited the experience of architects from the US and abroad regarding their competition experience. I obtained and analyzed competition codes, mostly European and Scandinavian, but also the AIA code (destined to be withdrawn for legalistic reasons). Two products of my research were the book Design Competitions (McGraw Hill 1978) and, subsequently, the Handbook of Architectural Design Competitions (American Institute of Architects, 1981).

Unlike most European and Scandinavian countries, where the conduct of design competitions has been carefully regulated, in the US it has not. Although the federal government has had a limited program for certain “high profile” public buildings in recent years, in 1980 neither by the federal government, the constituent states, nor, least of all the AIA, the professional design organization of American architects, had any established and mandatory procedure for conducting design competitions. That condition has not basically changed. Conducting design competitions in the U.S. remains voluntary, entirely dependent on the sensibilities and skills of a project sponsor and the people enlisted to assist in it.

A sponsor of the requisite sensibilities proved to be the VVMF, who contacted the AIA for professional help. Since I was chairing the AIA’s committee on competitions at the time, developing the AIA Handbook, I was recommended to the VVMF as professional adviser. My first discussions with them were in May 1980. My work began in July, the same

month that full authorization for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was procured. I worked directly with the VVMF Board and staff, but most closely with Robert Doubek, a West Point graduate and attorney.

Memorials and Competitions in Washington

Washington’s monumental character is the product of its 1791 baroque city plan and its largely neoclassic public buildings. That style also originates from the late 18th century. The earliest public buildings and monuments were products of design competitions — the U.S. Capitol, the White House, and the Washington Monument. Architect and later President Thomas Jefferson submitted seminal designs for the first two. Later works produced by design competitions include the Library of Congress, the Lincoln Memorial, and the Pan American Union. Inspired by Washington’s example, many of our individual states and municipalities utilized design competitions for their public buildings. One would think, then, that design competitions would be the norm for Washington, but that has not been the case.

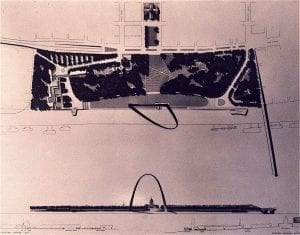

In Washington, unfortunately, the practice became problematical. In the 1930s a design competition for a new Smithsonian museum, the winning design authored by Eliel Saarinen, had failed. The original effort to create a memorial to President Franklin D Roosevelt (FDR) through a design competition in the late 1950s had also failed. Other then recent memorials in Washington included the WW II Iwo Jima Memorial, a memorial to Senator Robert Taft, and the John F Kennedy Memorial. None were the result of design competitions. Beyond Washington there had been several recent and successful contemporary American memorial efforts, procured through open design competition, much esteemed by the general public. One was the Battleship Arizona Memorial in Pearl Harbor, designed through a competition won by a WW II Austrian refugee, Alfred Preis. One of the finest of all American twentieth century memorials is the Gateway Arch in St Louis (the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial), designed by Eero Saarinen. It was the product of a very well conducted design competition held in the late 1940s.

The Gateway Arch, St Louis Gateway Arch competition drawing.

Battleship Arizona Memorial, Pearl Harbor, Hawaii FDR Memorial design, Washington DC.

Apart from the inherent difficulty of creating memorials in Washington, competitions aside, an equally grave reality was that after 1975 the American public was trying to put the Vietnam War in the past, in effect to forget it. The veterans and their families could not. Thus, while the idea of a memorial to our Vietnam Veterans was most deserving, considering both the difficulty of making memorials in Washington and the critical factor of public support, there was little reason for optimism on our part.

Federal Design Approval Agencies

Three century-old Federal agencies are responsible for the approval for the design of public architecture in Washington. To create a memorial in Washington it is essential to coordinate carefully with them. The agencies are: the National Park Service (NPS), which manages public park lands and virtually all of Washington’s memorials; the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC), which approves land use and design; and the Commission of Fine Arts (CFA), which approves design. I had worked with all three. Their staffs were colleagues and friends. I knew their roles and responsibilities. Without compromising our work these agencies were involved on a working basis, mainly informational, from the inception of our effort.

Source of the Design Competition Methodology

A popular characterization of the predominant public architecture of Washington, most of it of classically inspired, is to refer to it as “beaux arts style”. In France, where the Institute of Fine Arts was founded centuries ago (l’Academie des Beaux Arts), and which included a school of architecture (l’Ecole d’Architecture) the term “beaux arts style” has no meaning. They would refer to Greek or Roman neoclassic precedents. Jefferson had introduced the idea of classical architecture to the U.S., inspired by his travels in France. From the 1870s until the depression of the 1930s many of America’s leading architects had studied at the Ecole. Because of the Ecole’s emphasis on neoclassicism and because so much American public architecture was neoclassic, the term “beaux arts” became an identifying style, a “brand”. This unfortunate misuse of the term obscures more significant aspects of the Ecole and its teaching methods.

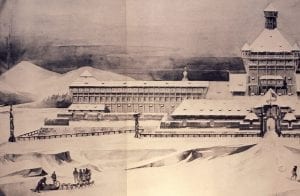

The Ecole is remembered for its extraordinary students drawings. Normally expressed with great graphic virtuosity the drawings were, foremost, exercises in developing a student’s design knowledge and facility, utilizing the most refined design palette of the western world. But Greek and Roman classicism were by no means all that they explored. Students also made detailed construction drawings. And they made designs for sites and climates far from the Mediterranean, even as far as Alaska, and so as different in architectural expression as the climates. Such exercises were far from neoclassic in motif. The Ecole was much more than a copybook of styles.

The Ecole was a school for learning how to design real and complex buildings. In the course of the nineteenth century France evolved into a Republic, and the Ecole’s students

explored the possibilities for many novel types of buildings – schools, hospitals, and courthouses were typical subjects. Representative example designs accommodated many complex functions into a coherent workable form. The designs were depicted in plan, elevation, and cross section. Rarely did the students do perspective drawings. Their drawings, consisting of the three-part plan-section-elevation depiction system, had to be analyzed by the viewer for all their implications – appearance, function, structure, circulation, construction feasibility, spatial experience and hierarchy, visual emphasis, light, ventilation, etc. The artistic virtuosity demonstrated in the drawings can obscure the underlying purpose of architectural depiction in plan-section-elevation. Unlike perspective renderings, whose purpose is largely to allure, the purpose of depiction in plan-section-elevation is to inform. In order to be understood such drawings must be examined analytically, like a physician analyzing an x-ray. Thus the concomitant to this method of depiction is that it requires expert and experienced eyes to evaluate. It requires jurors of long experience and extensive expertise. In a large array of designs, as in a competition, the normal condition in the Ecole, jurors had to be capable of evaluating a design rapidly, to see the essence of an idea at a glance. Plan-section-elevation depiction also puts all design submissions, as in a competition, on an equal basis of comparison, one design with another. Thus, the cornerstone of an effective design exercise and its proper evaluation, certainly for a competition, was and remains clear and fully informative depiction on the one hand and evaluation by expert jurors on the other.

The Ecole’s depiction method was disseminated world-wide, wherever competitions were held, and it persisted after the demise of the Ecole in the 1960s. It continues today. It has persisted because it is a very good idea. Not surprising, then, are Eero Saarinen’s original very good idea.

Not surprising, then, are Eero Saarinen’s original competition drawings for the St Louis Gateway arch —plan-section-elevation—the same technique used in the Ecole.

Construction drawing, L’Ecole d’Architecture. Project in Alaska, l’Ecole d’Architecture

True, Saarinen included a widely published perspective, but that was an accompaniment. The St Louis competition brief required the traditional and proven depiction triad.

The Memorial Site

Looking southward into the memorial site Looking eastward from the memorial site to the Washington Monument

The site for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, chosen with the guidance of NPS, was a small and quite inconsequential western corner of Washington’s central Mall, its monumental core. The selection of this site had been made by July 1980 when I was engaged as professional adviser. I concurred fully with the choice, feeling that if it were not possible to make a suitable memorial there it would not be possible to make one anywhere.

The site was a two-acre (0.8 hectare) area, a rough circle in form, 1000 feet (300 m) northeast of the Lincoln Memorial. To its east was an artificial pond called Constitution Gardens. To its south stood a row of neoclassic buildings of modest scale. The site itself was a quiet tree-lined meadow. Its special character, however, derived less from its interior, even less from what one saw looking into it, as what one saw looking out of it — looking from it. From the site one could see, principally, a striking view of the 555 foot high (169 m) Washington Monument 0.7 miles (1,120 m) to the east. To the southwest was a view of the Lincoln Memorial. The Washington Monument vista, unobstructed by trees, was clear throughout the year. The Lincoln Memorial vista is fully clear only in winter, when it is not obscured. Lesser vistas were of the US Capitol dome and several Smithsonian Institute landmarks buildings on the Mall. But the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial were the main vistas, giving the site its special value.

Competition Planning and Execution

Like any complex undertaking, a competition process has to be planned in complete detail, a sequence of coordinated actions all leading to an end product. The end product, the objective, was a realizable design concept that could earn the approval of the responsible agencies in Washington and, equally, the public.

A useful planning technique is to plan in reverse, to start with the end objective and work backwards to the beginning, identifying all the steps between. To plan, mount, and hold a design competition requires from nine months to a year, preferably less than a year. This allows adequate time without dissipating interest. A competition schedule must take into account the normal events of the year, such as holidays. Starting as we did in July 1980, we set May 1981 as the target date for having the competition design in hand.

The component phases were:

First, the planning phase, preparing an overall schedule for the entire process, preparing the various documents, the competition rules, the jury selection, the budget, prizes, logisitics, etc. The essentials were substantially completed by the end of September, two months after starting.

Second, the competition announcement phase, in which the competition was announced in the general media, the professional press, publications of all the design societies, and all schools of design. As soon as the competition announcement was made we began to receive inquiries. In response we sent a booklet describing the competition – site, rules, schedule, jurors, prizes, and the contractual relationship with the winner. We allowed three months for this second phase, ending at the end of December 1980, the registration deadline.

Third, the design phase, which began in early January 1981 by mailing the competition brief to all registered competitors and continued for three months. We allowed a month for competitors to ask questions regarding the brief. We studied their questions, the same question often asked by several competitors, and sent all competitors a question-and-answer document. The designs were due at the end of March 1981.

Fourth, the receiving and processing phase involved preparing the design submissions for review by the design jury. We received 1,432 designs, a then record. They were unwrapped, each assigned a code number, each checked for compliance, each photographed for a record, and all transferred to an airplane hangar for jury examination. This phase occupied three weeks, starting in early April.

Fifth, the jury phase, during which the jury examined all the designs, made their selection, and reported their recommendation to the VVMF. This occurred over a one-week period, beginning on Sunday, April 26 and continuing to the following Friday, May 1, when the jury reported to the VVMF.

Sixth, the design announcement phase, occupied the following week. It required the preparation of a press information packet and press conference. At the end of the week there was a public display of all 1.432 design submissions. Less than ten months had elapsed from initial competition planning to the public presentation of the design.

Seventh, the post-competition phase, entailed three critical and simultaneous tasks. The first was to obtain preliminary official approval for the design by the approval agencies. Second was to compose to a design team to develop the design. To do this an experienced and reputable local design firm (Copper Lecky) and an experienced builder (Gilbaine Building Company) were paired with the winning designer.

Third was a fund raising program. The U.S. government was to contribute the site. The memorial itself was funded by public subscription, including donations by more than 275,000 individuals. By early August 1981, two months after the conclusion of the competition, all three were accomplished or initiated.

Competition Working Documents

There were five principal working documents. They were:

The first document was related to the competition announcement, the “launch”. Along with press releases to the general and professional press and to the principal American professional design associations (architects, landscape architects, sculptors, planners) we prepared and sent an announcement poster to every school of design in the U.S. (architecture, landscape architecture, planning, and art). The announcement was an invitation to inquire about and receive information regarding the competition. Internet use at this time was virtually non-existent.

The second document, an illustrated booklet, was sent to anyone who inquired about the competition, which was open to any American citizen 18 years of age. This booklet described the purpose of the competition, identified its site, presented the rules, identified the eight-person jury, described the intended contractual relationship between the winning designer and the sponsor, and listed the prizes for the competition winner and runners-up. This booklet contained registration forms. Competitors could compete as individuals or teams. It was sent out immediately upon receipt of an inquiry. About 5200 inquiries were received in the fall of 1980, a rather assuring response.

The third document, also an illustrated booklet and site maps, was the competition brief. It was sent to all registered competitors, altogether about 2,600 individuals or teams, half the number of those who had inquired. It included plans of the entire mall and the site. The latter was illustrated in detail, showing topography, trees, benches, paths, and lighting. The brief was, for the most part, a description of the site. This booklet also enumerated the design requirements. We sought a design that were reflective and contemplative, that would be harmonious with its setting, that would not constitute a political statement regarding the war, that could be visited at any time or season, and that would not prove a maintenance burden. A further and essential requirement was that the memorial display the names of the 58,000 service men and women (eight nurses), who died or who were missing in action. This booklet also included the presentation requirements. Each design had to be presented on not more than two vertical panels each 30”x40” (76.2 cm x 101.6 cm). The design submission had to include a plan, section, and elevation, all at the same scale, the same scale as the site plan. A one-page written description was encouraged. All lettering had to be by hand, non-mechanical. Models would not be considered, although photographs of models were allowed. The competitors were free to add anything else, explanatory sketches, perspectives, etc. All drawing media were allowed. CAD was not in general use at the time. The booklet also described the requirements for wrapping and delivering the designs, as well as identifying the sender on the outer wrapping and having a sealed envelope on the rear of each panel, also identifying the designer or team.

The fourth document was the question-and-answer document.

The fifth document was a report on the competition results, sent all the individuals or teams who had submitted designs, 1,432 in total. The 1,432 submissions were the work of 730 teams and 2,550 individuals. A total of 3,843 designers participated.

Processing and Displaying the Designs

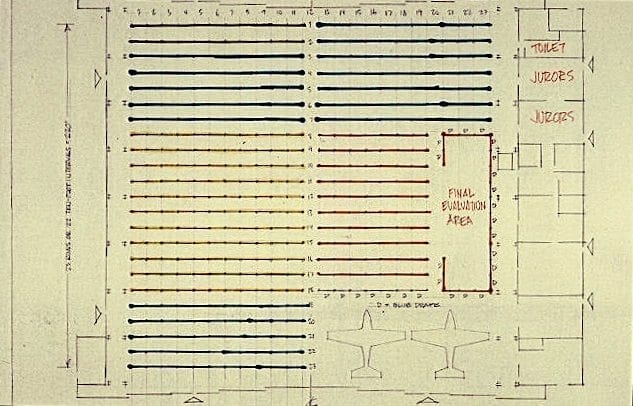

Hangar #3, Andrews AFB, Maryland

Exhibition plan for the 1,432 design panels

At the outset of this undertaking we realized that we might find ourselves in an atmosphere of opposition, possibly hostility, regarding the creation of a memorial related to the Vietnam War. As regards official Washington we were entirely wrong. The misgivings certainly persisted, but there was no lack of respect for the soldiers who had fought the war and who had died serving their country, the “rightness” or “wrongness” of the war aside. That manifested itself in the extraordinary degree of cooperation extended to us for conducting the competition.

The designs were received and processed in a large private mail-handling warehouse east of Washington. We needed such a facility for about three weeks. Here the designs were unwrapped, number-coded, photographed for the record, and prepared for display nearby. The use of the warehouse space had been donated, an example of the support the VVMF experienced throughout the competition process.

To display the designs for the selection jury we were generously offered the use of Hangar #3 at Andrews Air Force Base. The hangar had an unobstructed interior area of over an acre (0.4 hectare). We needed all of it. And the military security was a great help. We had to be prepared for possible anti-war protests. But none occurred.

We drafted a plan for displaying all 1,432 submissions, a linear 1-1/3 miles (2 km) of exhibit. I calculated that 3-1/2 hours were needed to walk by the entire design display, viewing each design slowly and without pausing.

In the receiving warehouse I had examined all the designs for rules compliance and to grade them very roughly into four categories of design merit – “highly promising”, “possible”, “unlikely”, and “ineligible”. I rated 191 designs in the two top categories. The exhibit arrangement, parallel isles, was such that jurors would pass from one “category” to another without being at all aware of that and without becoming influenced in any way, the two top category designs being in the more central aisles. The grading and arrangement was done to gauge how much time the jury would need and to facilitate repositioning the designs as the selection and elimination process proceeded. The finalists would end up being examined in a small court central to the main display.

The Jury

Jury: L to R: Weese, Hunt, Eckbo, Nivola, Rosati, Clay, Sasaki, Belluschi, Spreiregen

None of the members of the VVMF were designers or artists. Thus it became my responsibility to recommend the jury members. I did so by drafting a long list of candidates, designers I knew or knew of. The final list was drawn from those I was able to contact and who expressed interest in serving. I recommended that the VVMF interview each of the potential jurors individually. I excused myself from the interviews, preferring that the VVMF officers assess the potential jurors without my possible influence. All were accepted. In the case of sculptors I had recommended three, intending that two would be engaged. I recommended three because unlike architects or landscape architects the work of individual sculptors tends to be stylistically more identifiable. That might influence sculptor-competitors. But the VVMF liked all three and so three sculptors it was. The result was an eight-person jury, an even rather than the normally preferred odd-numbered jury.

In soliciting the American design community we wanted to appeal to designers of all types and predilections, professional and amateur alike. For that reason the jury represented the principal design disciplines. The selection jury was composed of two landscape architects, Hideo Sasaki and Garret Eckbo; two architects, Pietro Belluschi and Harry Weese; three sculptors, Costantino Nivola, Richard Hunt, and James Rosati; and one environmental design journalist, Grady Clay. All were highly seasoned and accomplished professionals. All were widely respected. Many had worked together, some in Washington. They were also most collegial, people who might deliberate intensely but were not at all likely to argue or posture. Four were veterans of other wars, but none were Vietnam veterans. That was intentional. In the initial planning phase the sponsor expressed interest in having one Vietnam veteran on the jury. I made no comment about this at the time, although I believed it was a bad idea. Such a juror-veteran might, I felt, skew the jury’s discussion with emotional argument. And which single veteran would be appropriate?…an officer or an enlisted man, an infantryman or an airman, someone who had served at the outset of the war or someone who had served at the end, someone who had been wounded or someone who had not? Fortunately the problem disappeared. One day the VVMF simply informed me that they had decided against the idea. There would be no Vietnam veteran on the jury.

The jurors started on their first morning by visiting the site together. They then went to Hangar #3 at Andrews AFB, and convened in a small meeting room alongside the hangar’s voluminous main space to discuss the program. Having done that they chose Grady Clay as jury chairman, and then went into the hangar to see all 1,432 designs individually. Each juror saw all the designs. As mentioned earlier I had calculated that a minimum of 3-1/2 hours was needed to view all the designs. The eldest juror, Pietro Belluschi, took a full day. By the end of the first afternoon one of the jurors, Harry Weese, came back to our impromptu conference room in the hangar and told me, “Paul, there are two designs out there that could do it”. One was to become the winning design.

Each juror, working individually, noted any design that appeared plausible to him. By the middle of the second day, Tuesday, 232 designs were noted by individual jurors. That was 41 more designs than I had designated in my top two categories, confirming to me that my screening and arrangement had not been prejudicial. Of these 232 designs 162 had received one juror vote each, 53 designs had received two votes, 10 designs had received three votes, and 7 designs had received four votes. The jury then viewed the exhibit collectively, pausing to discuss each of the 232 noted designs. Through discussion they cut the field to 90, then 39. As they did so they made remarks that clarified and defined the qualities that they felt were appropriate to the memorial. The final decision was made by early afternoon of the fourth day, Thursday. All the while one of the jurors, Grady Clay, a journalist, had been noting the remarks made by his fellow jurors in the course of the winnowing process. The selection made, Clay and I composed a report and explanation to the sponsor, based on Clay’s notes, to be presented the next day Friday noon, May 1, 1980.

Among the comments made by jury members as they reviewed the many designs, and noted by Clay, the following proved particularly cogent:

“I see something horizontal, not vertical.”

“Memorials that rely on symbols don’t work for a diverse culture.”

“In a city of white memorials rising this will be a dark memorial receding

“Many people will not comprehend this memorial until they experience it.”

“Most of the memorial is already there. It’s the site, and the vistas from it.”

“The design is like a Chinese vase – you bring to it what you are able to bring; you take away what you are able to take away.”

“A great work of art doesn’t tell you what to think, it makes you think.”

“You always experience a great work of art in different ways.”

“It will be a better memorial if it’s not entirely understood at first.”

“Confused times need simple forms.”

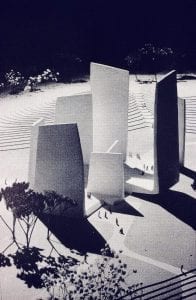

Third place design

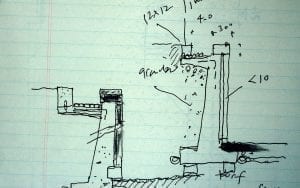

The jury deliberations were the most thorough and probing discussion I have ever experienced for any design, and I have participated in many. For example, Weese made several sketches showing how the design could be constructed. Weese’s sketches showed a concrete retaining wall supporting a finished stone face, a drainage system, and a small “stumbling curb” on the high ground above and behind the wall. Its purpose was to prevent people from inadvertently walking over the edge. At the time of the competition the “post modernist” movement was at its peak, and many of the submissions were of that inclination. They depended on allusion and symbol, a predilection that the jury found severely wanting.

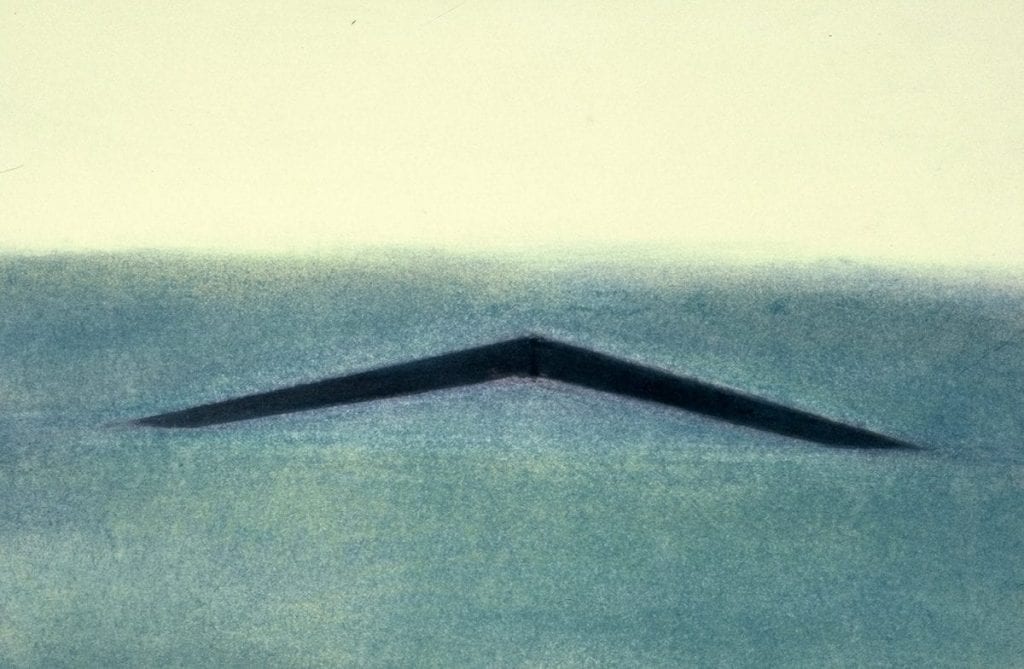

The selected design was the work of Maya Ying Lin, a then 21-year-old student at Yale University. Not only was the design far from the norm of Washington memorials, or indeed memorials anywhere, its depiction in pastel crayon was almost childish in character. Only a jury of the perspicacity of that eight-person panel could have found that winning design. A lay jury would certainly have overlooked it. A part-lay part-professional jury might well have become deadlocked over it, going instead to a more “acceptable” compromise design.

The jury’s recommendation to the VVMF not only had to be clear, it had to be convincing. It had to be understandable to a group of non-designers.

I called the VVMF office late Thursday to tell them that the jury was prepared to meet with them, that they had a recommendation to make. We would be ready at noon the next day. At noon that May 1 Friday about thirty people, VVMF and staff, arranged themselves in a large circle in front of the display of finalists, Lin’s design at the center, concealed under a cloth. That was lifted after a brief explanation of the jury process, followed by an explanation of the jury’s recommendation and reasoning, drawing on Clay’s notes. The presentation took 25 minutes. When it was concluded there was a brief silence, a matter of seconds. All looked to Jan Scruggs as originator of the memorial project to comment first. He rose from his chair, paused, strode forward, and in a calm and deliberate voice said, “Well, I like it.” The immediate reaction of all the others was to leap to their feet, clapping, cheering, and embracing one another. They understood it. At that moment my earlier misgivings receded. This memorial could become a reality. A new horizon came into view.

Maya Lin’s Design

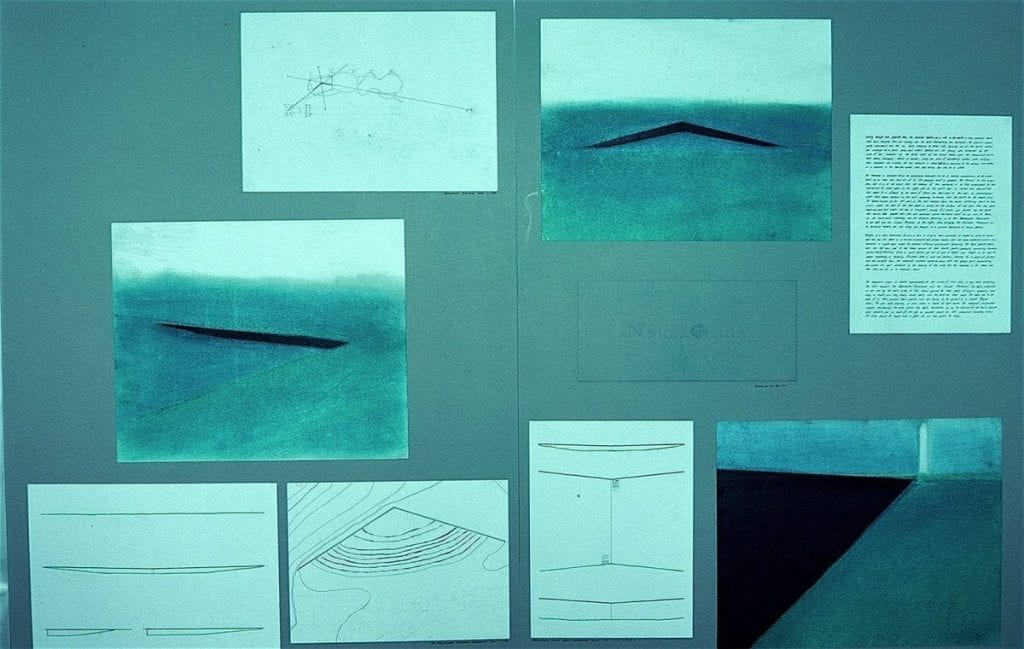

Maya Lin’s two submission panels

Lin’s concept of the memorial in the landscape

Concept of the vista to the Washington Monument Weese’s construction sketch

Maya Lin’s two panels showed, as required, a plan, a section and an elevation— plus supplementary drawings and a hand-written explanation. Altogether she had portrayed a fully convincing concept. One of Lin’s explanatory perspective sketches nearly said it all. It showed the view of the Washington Monument, looking eastward along the east wall of her memorial design. It confirmed what her plan-section-elevation-drawings suggested. One might speculate on the effectiveness of Lin’s seemingly naive drawings had she then had greater graphic abilities. Could she have been as clear? She may have been preoccupied with drawing to the detriment of thinking, as happens with presentation drawings. Her drawings served as a means, not an end.

Lin proposed that the names of the 58,000 war dead be arranged chronologically, in order of death, not alphabetically. The names would commence at the apex joint of two memorial walls and conclude at the joint base – full circle. They would disappear into the ground to the east and resume at the west.

She also showed how the design’s two-wall form derived from the utilization of the two principal vistas. The second place design also used the key vistas very well, but it was not as direct as Lin’s. It was more elaborate, while offering nothing more. In the final deliberations one juror commented, “This is how we might do it if it were for WW II”. Its designers, Marvin Krosinsky and Victor Ochakovsky, were two recent Russian immigrants. The third place design was the work of four landscape architects, Joseph Brown, Sheila Brady, Douglas Hays and Michael Vergason, with sculptor Frederick Hart. Its use of the vistas was good but not optimal. The vistas were to the Washington Monument and the less visible Capital dome, not the more immediate and more visible Lincoln Memorial. Again, a juror commented, “This is how me might have done it for WW I. The design we’re coming to – the Lin design — is a design of our times”.

In addition to the first, second and third prizes 15 honorable mentions were awarded. The teams or individuals who comprised these consisted of 23 architects, nine landscape architects, four sculptors, four students, and two artist-designers. The youngest was 18, the oldest 66. The average age was 38.

Lin’s design submission was the convincing portrayal of a raw idea. The jury saw in it the essence of what the memorial should be. They also

Model of Lin’s design, made for the press conference.

Lin with the model.

Dedication of thr Thiepval memorial, 1931.

realized that, as in all initial designs, much developmental refinement would be necessary. As it was, Lin’s topographical indications were somewhat muddled and the wall area she had shown was inadequate for displaying the 58,000 names. But these were minor shortcomings, easy to correct. It was the concept that was important.

In final form, and as built, the memorial is 246.75 feet long (75.2 m) and 10.1 feet high at the vertex (3 m). The two walls meet at an angle of 125 degrees. The two walls are composed of 70 inscribed panels. Ms Carla Corbin was principal staff architect for the “architects of record”, the Cooper-Lecky Partnership. She worked most closely with Maya Lin.

Genesis of Maya Lin’s Design

What were the origins of Lin’s design? The primary influence was indirect, less a specific precedent than a way of thinking about memorials to a war’s dead. The influence was the motivating idea behind the design for a memorial in Thiepval, about eighty miles northwest of Paris, a memorial to over 73,000 British soldiers “missing in action” in the WW I Battle of the Somme. Their bodies were never recovered, having been blown to bits or drowned in mud. The memorial was the work of the noted British architect Edwin Lutyens, and was a major departure from the glorifying memorials of his time, certainly of the 19th century. Lutyens was a master of irony. He was revolted at the slaughter of WW I. The Thiepval memorial, at first sight seeming to be a traditional and glorifying arch of triumph, is transformed in the visitor’s comprehension to become, instead, the jaws of death. It has almost no flags flapping in the wind. Real flags would be a token of life. Flags are carved in stone. They, too, are dead. From inside its many arches the outward vistas are of the former battlefields, the killing fields, now rolling pastures and farms, but once the landscape of death. Those rolling and fertile fields add a further sense of irony, the pointlessness of the sacrifice of young men to war. The arch surfaces are covered not with the expected referential and glorifying motifs but rather the thousands and thousands of names of the dead. Only that.

How did Thiepval idea influence Lin? There had been an exhibit of the British WW I memorials in Scotland a few years prior to the Vietnam competition. One of its curators, Gavin Stamp, was invited to lecture at Yale by architects Anne McCallum and Andrus Burr. Burr was the instructor of Maya Lin’s studio class, and assigned the Vietnam Memorial as one of four class projects. Lin learned about Thiepval at a lecture by Vincent Scully, a popular architectural historian then at Yale. Scully had learned of Thiepval from Stamp, and was subsequently credited for introducing it. Lin adapted Lutyens’ ironic attitude, first producing a pun of her own. There is also a memorial building at Yale, a student center, with the names of Yale alumni who died in all the nations’ wars inscribed on the interior walls of its main entrance. But Lutyens’ corrupted icon was the more significant source of Lin’s inspiration – with some coaching.

In the fall of 1980, when the competition was announced but before the brief was issued, Burr assigned four studio projects for his undergraduate studio class. One was the Vietnam Memorial. The class visited the site for the memorial that fall. At the time other scholars were exploring the subject of funerary architecture, the architecture of death. Lin completed three of the four projects, including the Vietnam Memorial. Her first design was a twisted human figure. Burr urged her to go beyond that. With the irony of Thiepval in mind she then did a pun on the once prevalent “domino theory”, the idea that if Vietnam were to fall to communism Southeast Asia would follow, hence a prevailing rationale for the Vietnam War. Lin’s initial design, her pun, was an array of large black gravestone-like slabs falling into a coffin, itself sinking into the ground with one corner protruding. It was the domino theory gone awry. A review of the studio work was held in the fall in which two New York City architects, Carl Pucci and Ross Anderson, participated. In the course of reviewing Lin’s “domino theory” design she was advised to delete the slabs, leaving just the protruding coffin corner. Another suggestion was that she put the 58,000 names on the visible coffin corner surfaces, starting at one corner of the coffin, disappearing into the ground and resuming on the other side. Lin listened to these suggestions. When the brief was issued in early January Lin made a refined design based on these ideas, drew them up quite privately and submitted her design in the competition. She had listened, learned and refined particularly well.

Public Announcement

The jury had made their decision on Friday May 1, 1981. A press conference and public announcement was scheduled for Wednesday May 6, five days after the sponsor accepted the design from the jury. It was obvious that Lin’s drawings would be insufficient, particularly for newspaper publication or TV broadcast. On the very same Friday I proposed that we needed to have two explanatory models illustrating the design. One was a simple model of the entire Mall, showing the visual relationship between the memorial wall positions, the Washington Monument, and the Lincoln Memorial. The other was a model of the design itself, showing topography, trees, and human figures to indicate scale. Weese, having a branch office in Washington, offered the help of his staff to make the models. I prepared drawings with minor toptgraphical

Public exhibit of the designs, May 1981.

Memorial dedication, November 1982.

Early on a winter morning.

In early spring.

corrections, and from that the models were built. Meanwhile, Lin was contacted in New Haven and told that some members of the VVMF would come to New Haven to confer with her. She hadn’t been told that she had won the competition. In New Haven the next day, Saturday May 2, she was informed that she had won, but that she had to keep this news completely confidential. Lin, accompanied by two VVMF staff, arrived in Washington about noon. At Weese’s office the models were by then well under way, the topography and wall positions in place. Lin noticed the slight adjustments, and although I explained that the model was only for the press conference, the public announcement, and for initial informational photographs, she was somewhat disconcerted. Her first remark was, “You changed my design”. I tried to persuade her that the design would likely “change” anyway in the course of its refinement, as indeed it did. Unfortunately, this encounter, though minor, was to foretell many ensuing difficulties, some of them severe, between Lin and the VVMF in the next months. But there were immediate needs to attend to.

Our objective at that moment was the press conference and announcement a few days later. The models had to be completed by Sunday so that they could be photographed for informational use as enclosures in a press kit, an information package, to be distributed at the press conference. Upon meeting Lin we knew that the story would concern not just the memorial design but, as newsworthy, the designer as much and possibly more.

On Wednesday May 6 the Boardroom of the Headquarters of the American Institute of Architects was filled with print and TV press reporters, TV cameras and cables covering the floor. The announcement would be national news. We composed the announce-ment presentation with the greatest care. Our press kits were ready, com-plete with the photographs that we felt would convey the memorial design effectively. The models were in place, covered. We knew, also, that the impact of the presentation had to be “love at first sight”, that the design had to win immediate public acceptance – through the press reports to be sure – or the project was dead. We had to do it exactly right.

Our presentation plan was centered on the design and on Lin as the winner of the competition, having her explain her design. Scruggs and Doubek were to make brief introductory remarks. I was to follow, describing the competition process and design selection, also speaking briefly. This background information was, of course, necessary. Its larger purpose was to heighten the press audience’s anticipation for the design and its author. We wanted maximum impact.

Lin was young, diminutive, and Oriental. She wore a pork pie hat. She might easily stand out in a room full of reporters. She might be spotted, lessening the surprise. To avoid that we arranged for Lin and my wife and long-time assistant, Rose-Helene, to arrive at the press conference shortly after the preparations started. The two were to carry reporter’s notebooks and quietly seat themselves in the rear of the room, blending into the frenzy. So they did.

Scruggs made the opening remarks. Doubek made further introductory remarks. I followed, describing the competition process – the jury, the number of entries. In concluding, my words slowing, I said, “I would now like to introduce to you the winner of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Design Competition … Maya Ying Lin”. This was her cue. Following our plan she counted slowly to ten, rose, and then walked slowly from the rear of the room to the podium.

She then presented her design. The presentation, carefully rehearsed, consisted of slides of her drawings interspersed with actual views of the site, blending reality with possibility. Her accompanying narrative was, simply, a reading of her hand-written design description, the narrative she had included on her presentation panels. The whole presentation took about thirty minutes.

The response could not have been more positive. Photos were made of Lin and Scruggs holding the model. The story went out immediately on all the major wire services. It was feature news on evening TV. Many more news stories were to follow. Many editorials were written, overwhelmingly favorable. There were many laudatory “letters to the editor” of the major newspapers.

Following the press conference and public announcement, we made a second presentation to members and staff of the U.S. Congress on Capitol Hill, including the memorials patrons, Senators Mathias and Warner. CFA, NPS and NCPC staff were also present.

After the Competition

All of Washington’s memorials were subjects of controversy in their time. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial was no exception. In all cases the contro-versies caused the realization of the past memorials to be delayed – the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial both a half century. The controversy that ensued over the Vietnam Veterans Memorial has been amply described in the book To Heal a Nation by Jan Scruggs and Joel Swerdlow, as well as a more recent book, The Wall: 25 Years of Healing and Education by Kim Murphy. Fortunately, I was not directly involved in the controversy, though I remained close to Scruggs, Doubek and the VVMF. My role had ended with the conclusion of the competition and the

Eastward vista to the Washington Monument.

Southwest vista to the Lincoln Memorial.

The names and background reflection.

A commemorative anniversary.

formal approval of the design by the CFA, NPS, and NCPC by August 1980. The controversy became vicious and the tactics quite underhanded. To my deep regret that controversy became another slur against competitions, even though controversy can and often does occur as often with commissioned work. When a problem arises the competition process gets blamed; the commission process does not. Through all this Lin performed admirably, standing up to an onslaught of harsh criticism. She never wavered, and she and her design prevailed. But Lin had her limits and in time resigned her role as design consultant. The design survived the controversy and the memorial was built, dedicated only 28

months after competition planning started, 18 months after the design was first presented. Final permission to build the memorial was granted by then Secretary of the Interior James Watt when the VVMF agreed to add a flag and, of greater impact, a statue group representing Vietnam soldiers on patrol. This compromise was reached through the critical intervention of Senators Mathias and Warner, and through negotiations with the CFA, NCPC, and NPS. The procedures of these agencies can be credited with protecting the original design. They assured that the placement of the flag and the statues would not compromise Lin’s basic concept.

On Saturday May 9, three days after the public announcement, we had an open house exhibit at Andrews. All 1,432 designs were displayed. The hangar was filled. The memorial dedication took place on Nov 11, 1982. That was the first of two dedications, the second being two years later for the soldier sculptures and flag. President Ronald Reagan did not attend the first dedication. Vietnam was still too politically sensitive an issue. But he attended the second, for the statue and flag. By then the memorial had succeeded in surmounting the divisive scars of the war. Its creation had far surpassed Scrugg’s original hopes. It had indeed become an act of tribute as well as reconciliation. Almost immediately it became an American icon.

Afterthoughts

Although these events took place over a quarter century ago they remain vivid in memory, aided of course by my log books and papers. There are several thoughts and recollections that I would like to add.

When I began my work as professional adviser, I made a personal pledge – that this competition was going to be one of the best ever conducted. I wanted to establish— or, more modestly, reestablish—a model. I thought, too, that it would be a miracle if we were able to get any memorial at all built, but if we did, we might open a Pandora’s box, that there would be many more memorial efforts to follow and that these, regrettably in my view, would be predominately war related. My first hope, that this competition as a model procedure would set an example, was not realized—although competitions came into wider use as a result of our success. The second, that there would be many war related memorials, was.

In the entire course of the work none of the members of the VVMF, all veterans, ever asked about my personal views regarding the war itself. Nor did they ever discuss theirs. I believe we were of similar minds.

The public exhibit at Hangar #3 on Saturday May 9 also stands out. The broad public interest in the memorial effort and the competition can only be described as spectacular. I met many of the competitors then, most of the winners among them. Especially memorable were two recent Russian immigrants who had won second place, Krosinsky and Ochakovsky, who smothered me with great bear hugs and proclaimed, “This is democratic architecture!”

Coloring these recollections are the inspiring words of the Swedish architect Ragnar Ostberg, written in his 1929 book about the Stockholm

Town Hall, for which he had won the design competition held from 1902-05.

“At the office days lagged on in grey monotony, from time to time relieved by the frequent competitions, sometimes resulting in a prize, though usually not, or by the week-ends, which afforded opportunities for architectural studies in various parts of my own country.

…but I was still kept waiting for the great chance…”

Ragnar Ostberg received the Gold Medal of the American Institute of Architects in 1933.

Paul D Spreiregen, FAIA

Architect

2215 Observatory Place NW, Washington, DC 20007, USA

(202) 337-2887 paulspreiregen@verizon.net