by Miguel Ruano

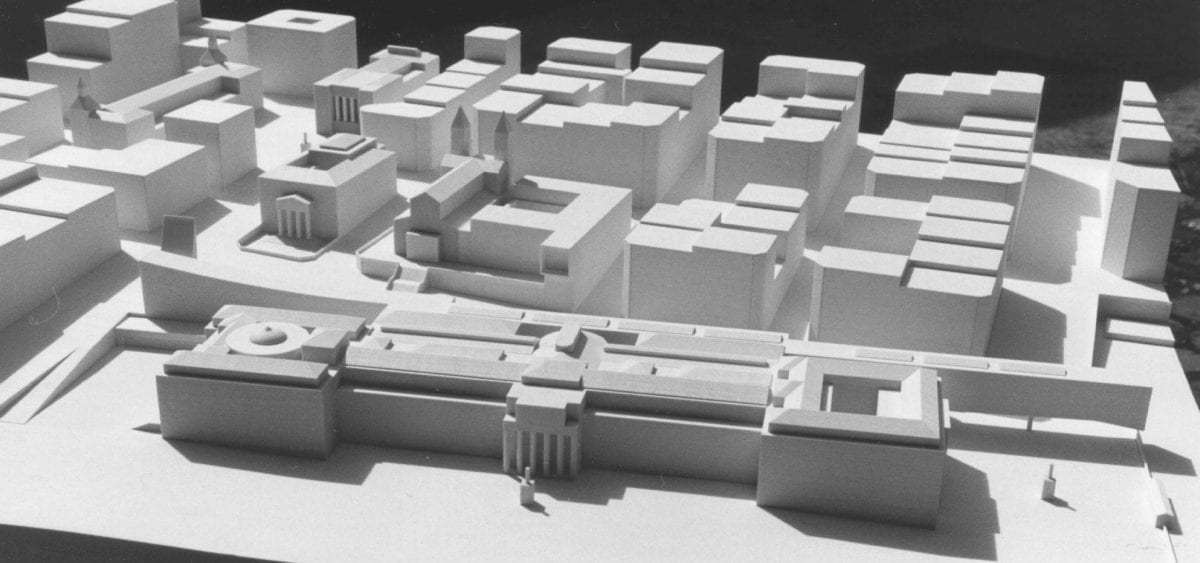

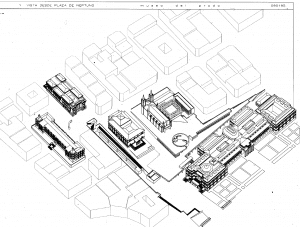

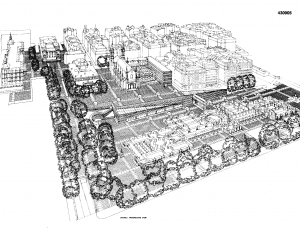

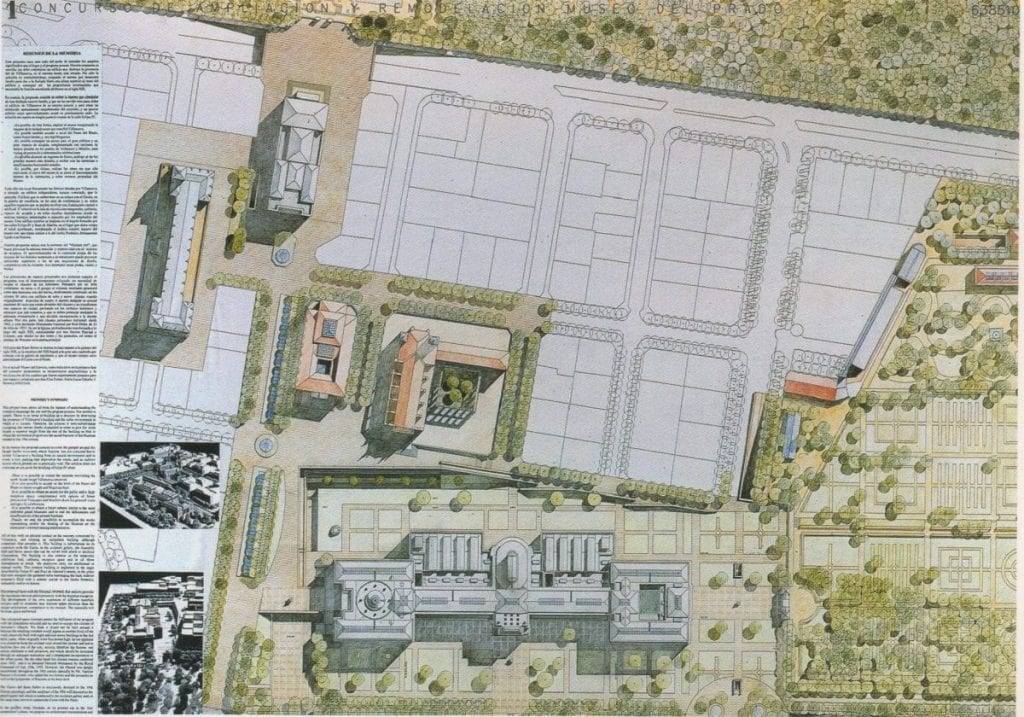

Aerial view of Prado (left); site outline (right)

In October 1993, rainwater was seen filtering down through the cracked, poorly maintained roof of the Prado museum’s 18th century building, directly threatening some of the world’s greatest masterpieces, including Velazquez’s “Las Meninas.” Alarm bells went off, both in the building and in the media, and the public learned what until then only a few insiders knew: that one of the best and most famous museums in the world had been in desperate need of repair and expansion for decades. As an emergency solution, seven architects were requested in 1994 by the Ministry of Culture to submit their own ideas for the refurbishment of the museum’s roof. At the same time, the notion of a more ambitious, high-profile international competition to design an extension to the Prado began to take shape.

The competition was to be organized by the Ministry of Culture of Spain, with the technical assistance of the UIA (International Union of Architects) and UNESCO’s endorsement. With government elections coming up, the politicians in charge of the problem needed to demonstrate that the Prado was a high priority.. Thus, the media was immediately informed to ensure complete and regular coverage. From the start, the competition took on the character of a political public relations affair, which in the end, would come back to haunt them.

The Rules

The Prado Competition began in earnest in February 1995, when the Museum’s board of trustees approved the competition rules, which were in turn accepted by the Ministry of Culture of the ruling Socialist Party. In theory, there had been a top-level agreement on the approach to be taken to address the museum’s problems between the Socialist government and the main opposition party, the Conservatives, who by then were already expected to prevail in the next election. The reason for such agreement was obvious—to make sure that the process would not be overturned for political reasons.

Subsequently, it would appear that this agreement had been on a shaky foundation from the very beginning. According to the rules, which were fraught with ambiguities and inconsistencies, the Prado was going to double its size to 40,000 m2 by the year 2000 via its expansion into three adjacent buildings. This brought about the first conflicts, as some of the owners of the buildings in question denied any association with the expansion plans. This included Spain’s Catholic church, which took the Ministry to court. Madrid’s City hall, already under Conservative Party control before the elections, hardly appreciated such a high-profile initiative taken by the lame-duck Socialist government—directed at the very heart of the city. Moreover, at the insistence of the Museum’s Board of Trustees, a clause declaring that the “current architectural image of the main building could not be disturbed” had to be included in the rules (and it was). The original competition schedule had to be delayed two months, and last-minute, but significant, amendments had to be made to the rules, giving everyone a feeling of improvisation. The whole venture started on a note of controversy.

The Entrants

According to the organizer’s estimates, 500 architects from all over the world were expected to register for the competition. Some were individually invited to enter, including Isozaki, Ando, Hollein, Wilford, Salmona, Macary, Pelli and Siza (who immediately declared he would not take part, and then was asked to become a member of the jury, to which he said no as well). Others, like Foster and Calatrava, both well-known to the Spanish general public, had already confirmed their interest, which raised everybody’s expectations after their much publicized showdown at the Reichstag competition in Berlin.

Finalist – Distinction (2)

Alberto Martinez/Beatriz Matos

Madrid, Spain

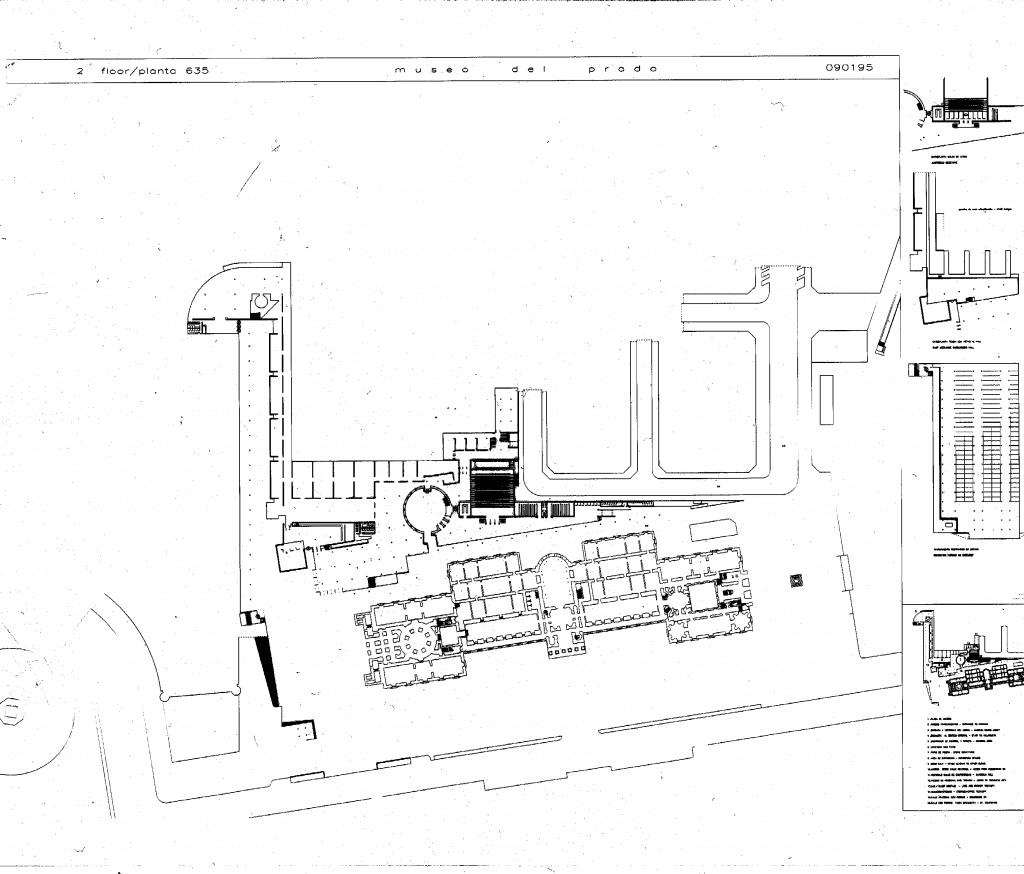

Second Place in First Round (11 votes)

This low-impact proposal creates a new urban space in front of the Prado’s historic building back elevation, which now acquires a new character as an urban facade. Below this platform, a new three-story underground structure houses the entrance hall, auditorium, cafeteria, library and storage areas. A transversal gap across the plaza brings natural light into the underground structure. From this, the building connects with a new adjacent structure, located on the old covent’s grounds, which houses the museum’s services (restoration workshops, offices, etc.) -MR

Images from competition boards ©Ministry of Education and Culture

As architects learned more about the competition’s details, skepticism and even open criticism heightened—from architectural circles as well as in the media. Some internationally famous names such as Ungers or Ando decided not to register, arguing either work overload or disagreement with the competition’s rules. The organizers, however, seemed to be satisfied with the fact that well-known architects like Foster, Moneo, Calatrava, Tusquets, Bohigas, Navarro, Eisenman or Benevolo had decided to enter, thus giving credibility to the initiative.

Interestingly enough, while the organization was obviously very forthcoming in disclosing names of high-profile participants, they would not supply a complete list of entrants, arguing that the competition was anonymous and, as a consequence, only overall registration statistics could be released.

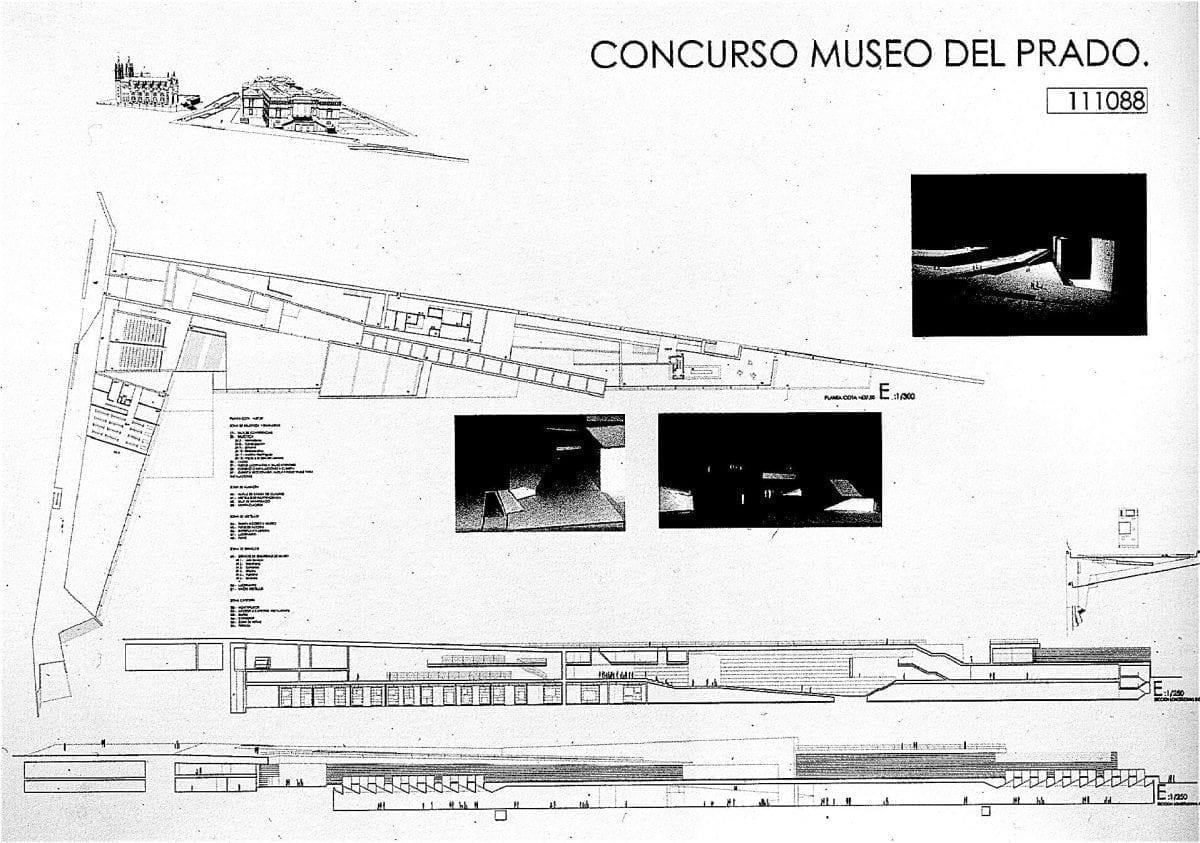

Finalist – Distinction (2)

Jean-Paul Duerig and Philippe Rami

Zürich, Switzerland

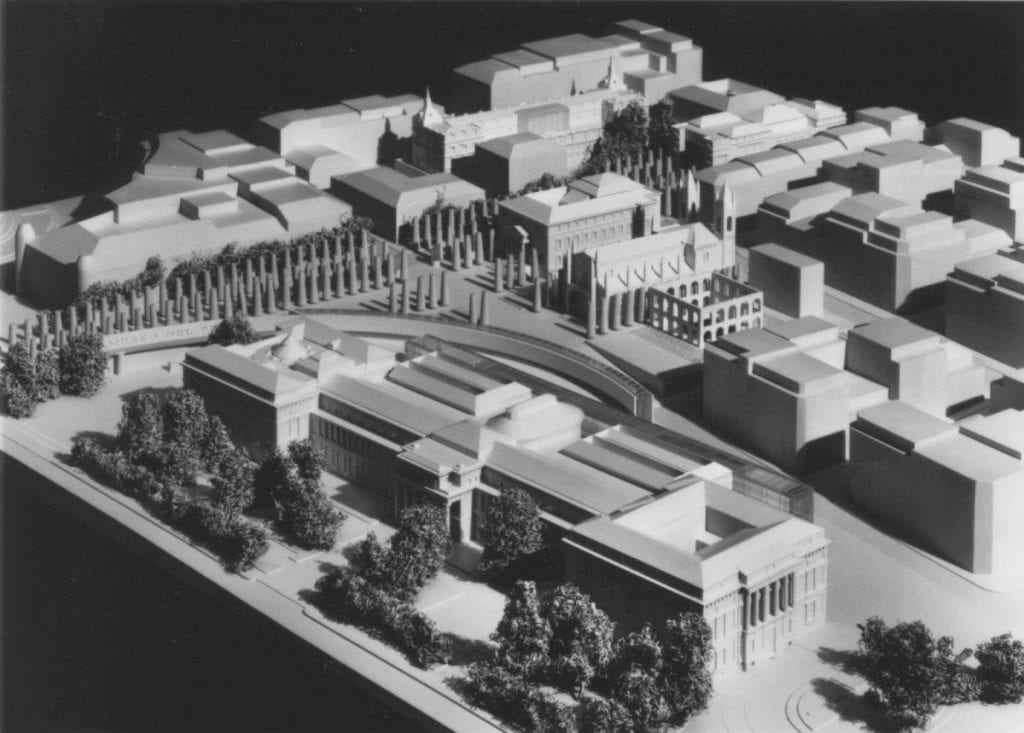

Seventh place in stage 1 semi-final round (6 votes) – tied with E. Zoido

This blunt proposal attaches a new gray granite and red brick structure, 300m (1,000 feet) long, to the Prado’s rear facade to house the entrance hall, exhibition halls, auditorium, cafeteria and shops. The nearby convent becomes a four-story building for the library, the restoration workshops, and the museum’s services and offices, while the old building will be used exclusively for exhibitions. The whole museum complex (four existent buildings, plus the proposed structure) are linked by underground connectors. –MR

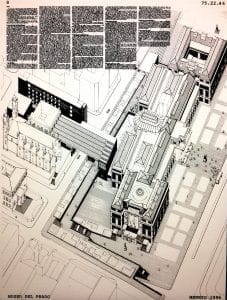

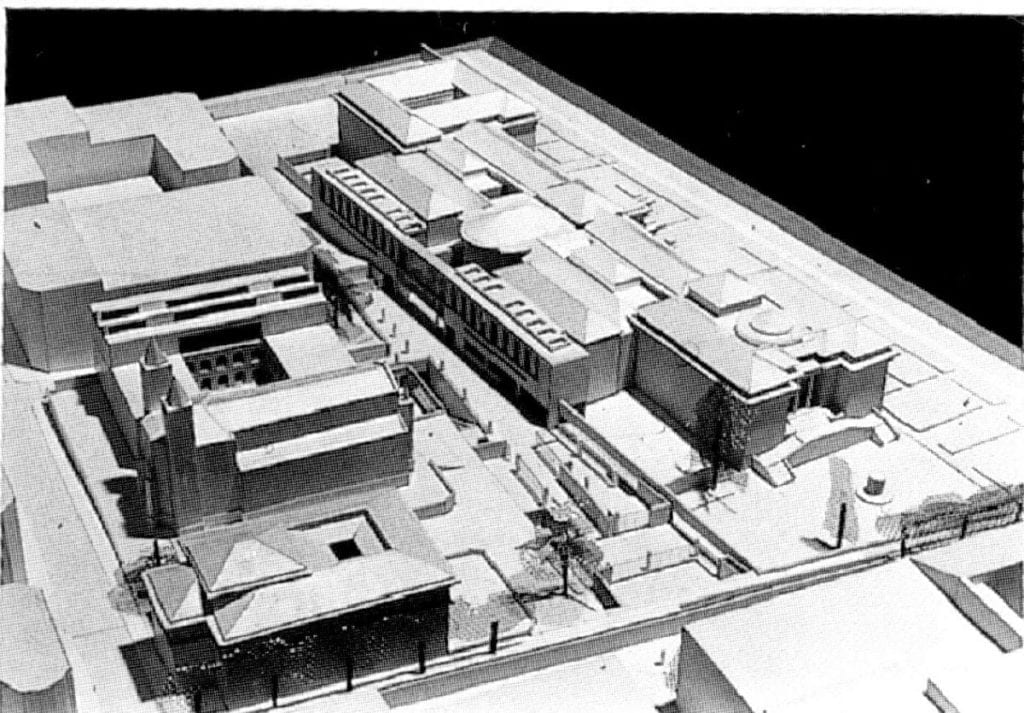

above

Aerial view of model

left and below

Images from competition boards ©Ministry of Education and Culture

The Jury

The rules stated very clearly, both in English and Spanish, that, in the first stage, a maximum of ten entries and a minimum of five would be selected to enter the second stage. Furthermore, the rules also established unmistakably: “in the Second Stage of the Competition, three prizes will be awarded. A first prize of 3M pesetas (US$24,000) and the commission for the final design of the works that form the purpose of this competition, and two distinctions of 2M pesetas (US$16,000) each.” The finer print, however, stated, “the first prize may only be awarded if there is a majority of two-thirds of the (jury) members present.”

The intended jury was a large and heterogeneous collection of fourteen members, so it became clear to many observers that reaching a two-thirds consensus would not be easy. Only eight members of the jury were architects (Botta, Duro, Eytan, Hertzberger, Hollein, Ramirez, Venezia and Salmona), and only one of them, the president of the UIA (Duro), was from Spain (albeit from Barcelona, not from Madrid). None of them were particularly familiar with the Prado’s problems, the museum’s urban context, or Madrid’s idiosyncrasies. The other six members of the jury included the Socialist Minister of Culture (expected to be replaced by a member of the Conservative Party between the first and the second stage of the competition), the Mayor of Madrid, the Undersecretary of the Ministry of Culture (also expected to change), the President of the Prado’s Board of Trustees, the Prado’s Director (expected to be replaced as well) and the Prado’s Assistant Director.

The Response

1,620 teams finally registered for the competition by the June 1995 deadline. These included 514 (32%) from Spain, a country with 24,000 architects for just 40 million inhabitants (0.6 architects per each 1,000 persons versus 0.3 in the U.S.), where work is extremely scarce nowadays; so the competition raised many expectations there. But this was not only the case with Spain: there were 184 registrations from Italy, 146 from France, 104 from the U.S., and 84 from Japan, these being the countries with the highest representation. The list of 55 countries was truly international, including places like Bosnia, Namibia, Croatia, and Cuba. Many of the entrants traveled to Madrid from far away places at their own expense just to participate in one of the eight tours of the Prado.

The competition registration fee was $250, meaning that the organizers collected US$405,000. The overall competition budget, for a project estimated to cost 20 billion pesetas (US$ 60M) was just US$640K, 0.4% of the total project cost. However, 63% of this amount ($165,000) had already been contributed by a private foundation, which meant that the organizers generated a surplus of US$165K from the very onset. These museum issues resurfaced again later in the game.

By November 1995, some of the famous international ‘names’ had decided to abandon the competition. These included Bohigas, Tusquets and, most important, Foster, who reportedly declared to the press that the competition rules rendered impossible any appropriate and economically reasonable solution to the problems of the museum and its urban context. In his opinion, the museum’s interests would be best served by intervening mostly in the current building, something the rules practically forbid, and by leaving the other three buildings pretty much in their current condition, which went directly against the requirements for their inclusion established by the rules. Foster’s opinions were supported by several architects, including some famous competition drop-outs, and even by the former director of the Prado under the Socialist administration.

Foster, according to one press report, had decided to continue working on a proposal that he intended to show publicly outside the competition framework, ‘as a contribution to the civic debate on the museum’s future.’ The media did not waste such a news opportunity, informing the public on a regular basis about Foster’s intentions and actions. To date, Foster apparently has shown his well developed proposal injust one public Spanish venue, at the widely publicized Seminar on Museum Architecture, which took place in Santander in July 1996—while the competition’s second stage was still in progress! At the same venue, the newly appointed Director of the Prado Museum replied to Foster that ‘if 1,620 architects from 55 countries had registered for the competition the rules could not be that bad.’ However, ‘due to the respect and consideration that he felt towards Foster and his work,’ he agreed to meet with the architect ot discuss his ideas and his design proposal for the museum’s expansion. All this was reported in etail by the national press, and Foster’s modus operandi, as well as the organizers’ seeming willingness to embrace it, generated outrage among other architects, particularly among Spaniards, participants in the competition or not, whose less-known names would not give them the grounds to pursue a bold strategy.

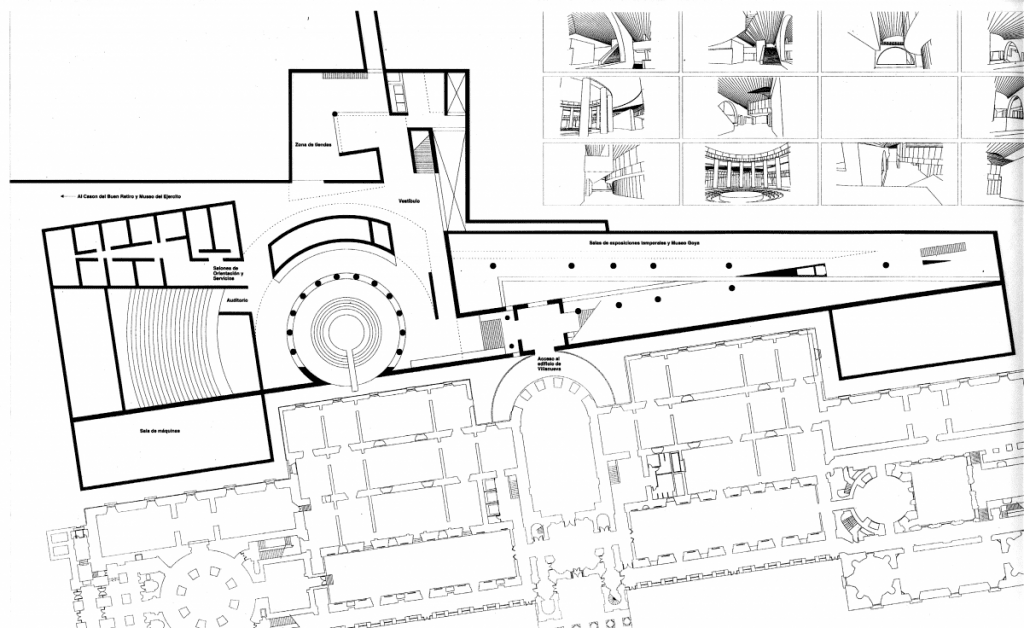

Finalist

Alfonso Govela

Mexico City, Mexico

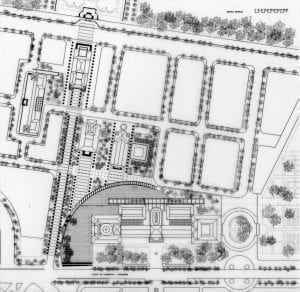

First place in the semi-final round (12 votes)

Govela uses a series of platforms and monumental stairs to hide a three-story underground structure, located and at the rear of the Prado’s current main building. This structure houses the entrance area as well as the connections between the four buildings of the new museum complex. The underground building is lit by a circular courtyard. -MR

Images from competition boards ©Ministry of Education and Culture

The First Stage

Only 482 entries (less than 30% the number of registrations) were submitted for the first stage of the competition, of which 30% were from Spain. The2,892 A-O boards (six per entry) were mounted on a temporary exhibition, 4km (2.5 miles) in length, for the jury’s eyes only, at the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid, at a cost of 15M pesetas (US$115K). Each foreign jury member received a daily allowance of just US$500 for living expenses, and no honorarium, in accordance with UIA regulations. The organizers themselves told the press that they estimated that each entry was worth on average at least 2M pesetas (US$15,000); implicitly acknowledging that they had collected a 964M pesetas (about US$7.5M) value in architectural design effort for a much lesser cost (a factor of 12-1).

The composition of the original jury changed slightly, with the unexpected participation in the jury sessions of Chwalibog as replacement of Botta in the last vote (Chwalibog was officially the just-in-case replacement for the UIA’s appointee, Ramirez and Eytan, both present). The Mayor of Madrid delegated Rodriguez-Avial, the architect in charge of Madrid’s urban planning agency to take his place on the jury. This increased the number of votingarchitects on the jury to nine, including the two Spaniards.

According to press reports, some members of the jury had declared their intention to persuade the organizer to increase the number of entries to be selected for the second stage and to raise the pecuniary compensation (US$16,000) per second-stage entry, which had been amply criticized in professional circles worldwide as too meager for an undertaking of such magnitude and significance, especially considering the amount of money generated through the registration fees. Only ten entries were eventually selected, and the compensation was not increased.However, the Ministry of Culture requested the submission of a 1/500 scale model for second state proposals, the cost of which, up to US$16,000 would be reimbursed by the Ministry.

Finalist

Jesus Marco

Taragoza, Spain

Sixth place in the semi-final round (7 votes) – tied with Moneo and Pardo

The proposal is based on a series of platforms whch take advantage of the site’s topography. According to its author, there is no ‘new building,’ just ‘new space.’ There are no facades, only terrace-roofs and a circular space made of stone. The original building remains untouched. Below the terraces, an underground structure houses several museum functions. -MR

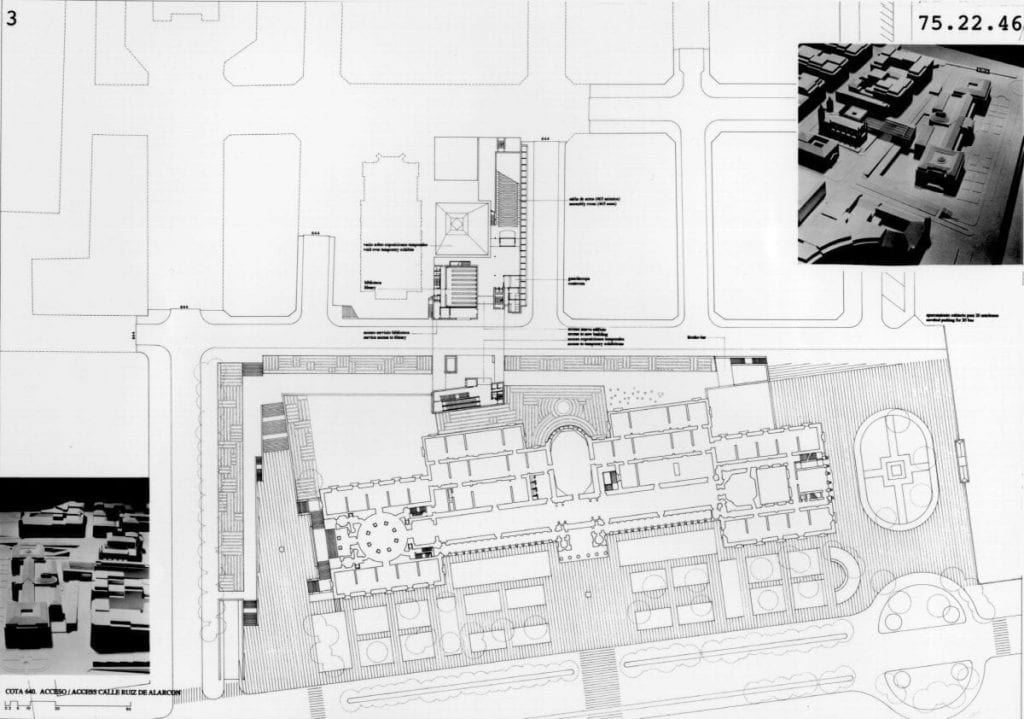

Plan (above) and Axonometric (top) Images from competition boards ©Ministry of Education and Culture

The jury meetings for the first stage, lasting four days, lasted a total of 28 hours, suggesting an average time of 3.5 minutes per entry. During the first round, the jury reviewed a total of 2892 m2 (31000SF) of drawings in one and a half days, giving each juror an average of about a minute and a half to review every single entry (equivalent to about 15 seconds per board). 107 entries were selected after the first round, 23 after the second, and five after the third. The jury then went back and finally settled on ten entries, reportedly voting unanimously to proceed in this manner into the second stage. “Jury sources” allegedly let it be known that the ten entries covered a wide spectrum of design approaches and stylistic tendencies, reflecting “everything that is currently happening in architecture today, from minimalism to the spectacular.” The same sources explained that allten entries were “progmatic, feasible and sensible,” as “crazy concepts had been filtered out,” and that “big names” could not be recognized among the selected entries.

Since the whole process was still anonymous, thenames of theten selected firms were not made public at the time. The firms were contacted privately, via a notary public, who informed them of the jury’s decision.

The Second Stage

Months passed and, while the selected firms were working on further developing their proposals, rumors spread as to whom the ‘chosen ten’ were. Even the most respected national press organs (“ABC”, “El Pais”) published articles disclosing the names of some of the ten firms, including Rafael Moneo’s, Spain’s shiny winner of the Pritzker Prize, and who, according to some reports, was the ‘in pectore’ winning contestant. Criticism against the competition organizers centered around the fact that while a very complex, long and expensive process had been designed to be totally confidential, for the purpose of preventing undue external influences, the organizers or individuals close to them appeared to be disclosing information when they found it convenient, presumably to obscure political and commercial interests.

When the competition jury met again in September 1996, there were many changes in its composition compared to the previous incanation: the Minister of Culture (now Minister of Education and Culture, the two departments having been joined into one or, as some critics say, the latter was phagocytized by the former), the Undersecretary of the Ministry and the Museum’s Director were totally different individuals as a result of the Conservative Party’s victory in the elections in March of that year. If this wasn’t bad enough, Hollein and Ramirez were also absent. Apparently, Hollein, wo had to come from Austria, had requested an honorarium on top of the US$500 per diem living allowance, a demand which was rejected by the UIA. He also requested a view of the hotel room where he would be staying. In the end, he explained he would not be able to travel to Madrid for the second jury session due to his prior commitments as Director of Venice’s Biennale. He ws replaced by Chwaliborg.

Ramirez cited personal reasons for not coming. AS he was not replaced, the jury was reduced to thirteen members, three of them unfamiliar with the decisions and criteria followed during the first stage selection process. Only six members of the second jury (less than half) were architects. A two-thirds agreement (nine members) was still required to award the first prize.

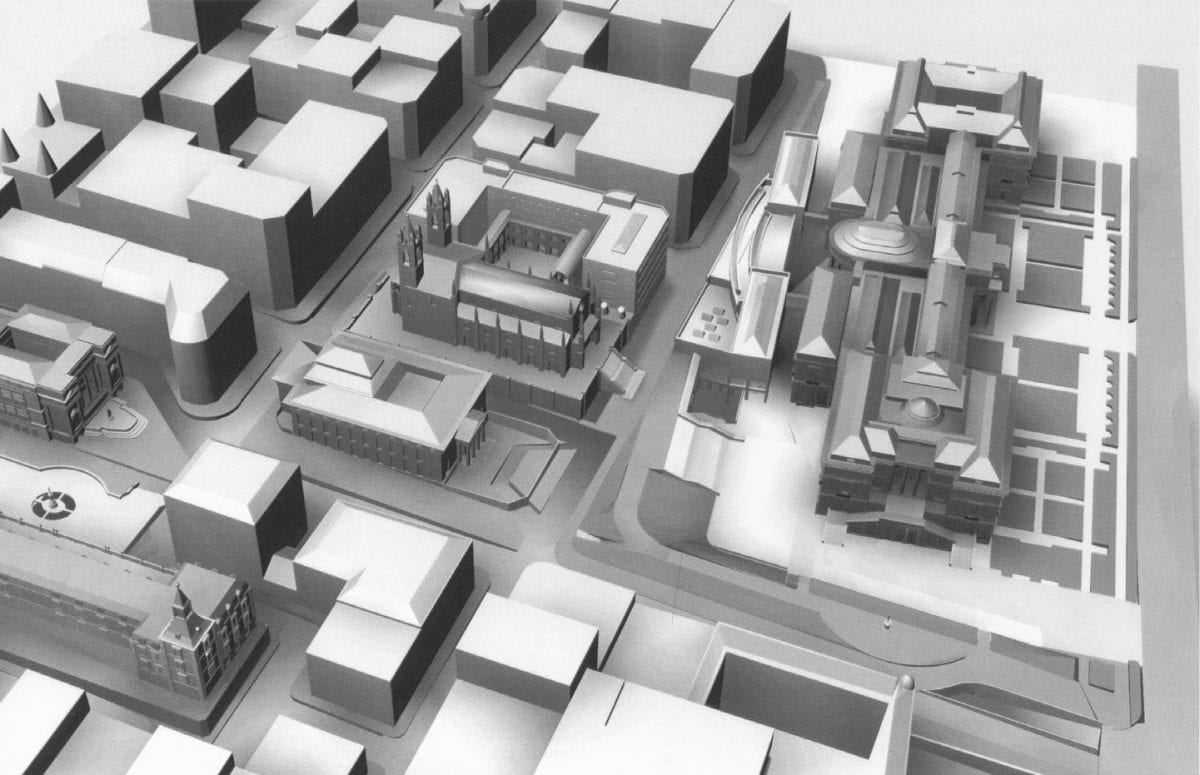

Finalist

Eleuterio Poblacion

Madrid, Spain

A new depressed open space with the shape of a circle’s arc is created at the rear of the current building, fiving access to new exhibition spaces located in the basement and lit through a glass prism. This underground structure also provides links to the other museum structures, but using what otherwise would be just corridors as multimedia galleries. The whole urban area around the current museum building is refurbished as a public space with gardens and plazas. -MR

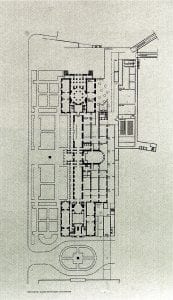

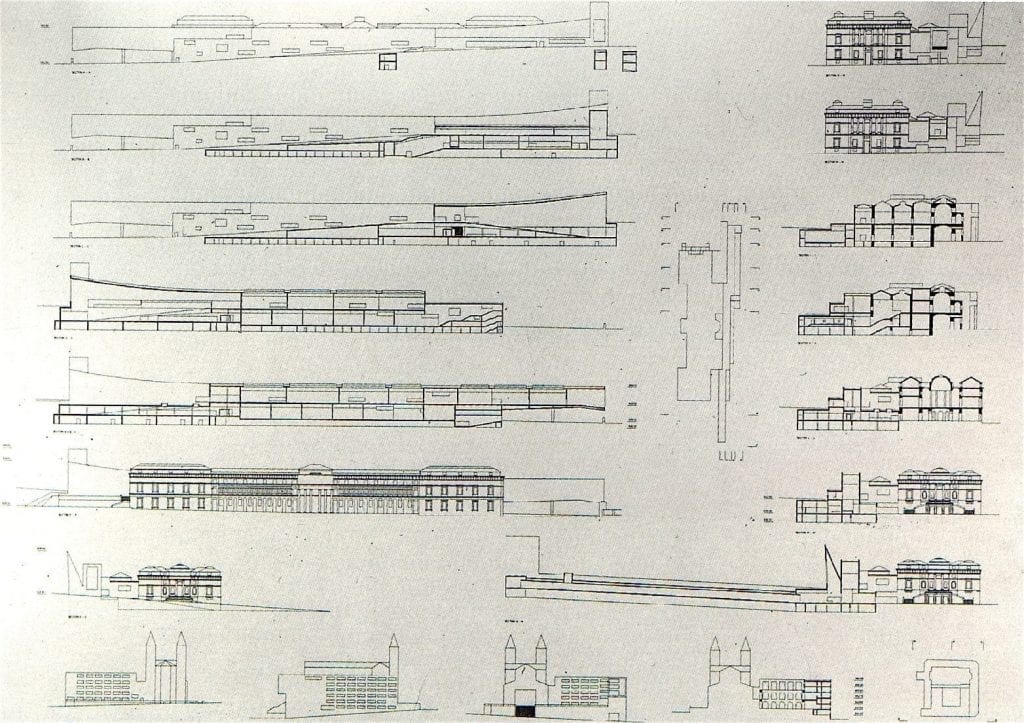

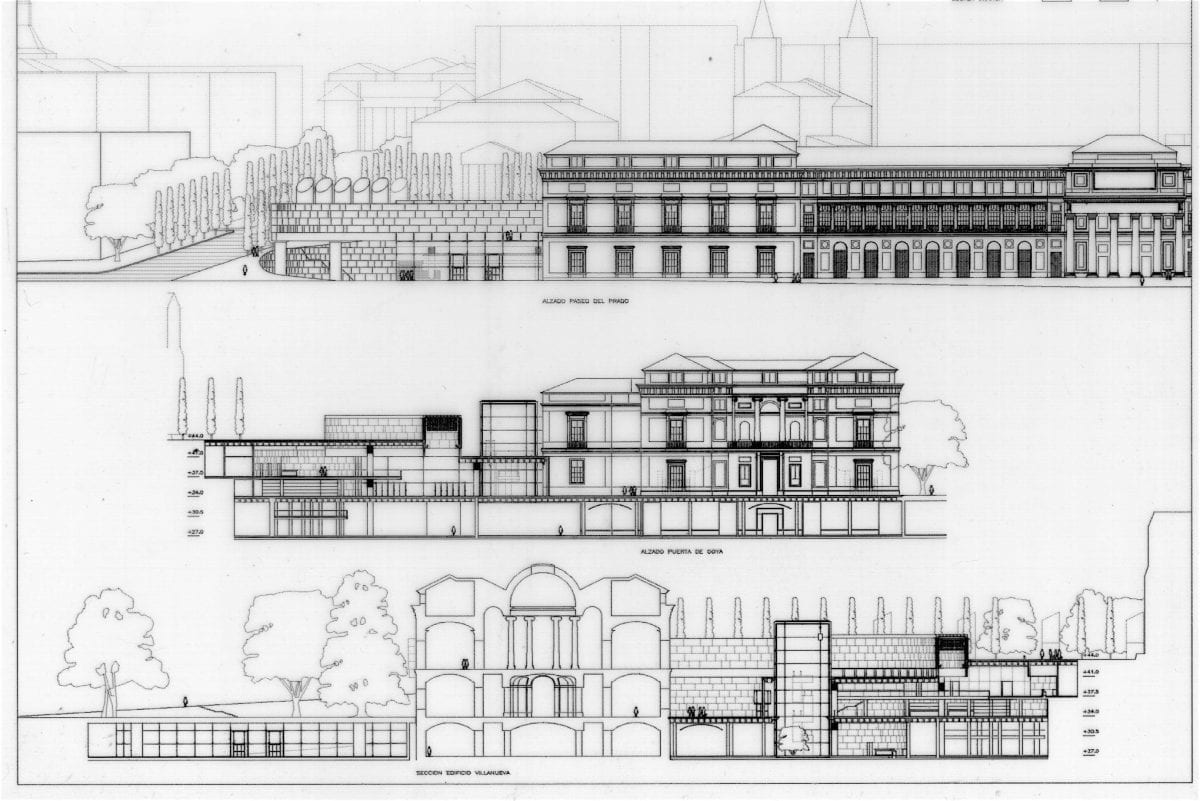

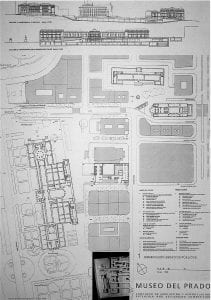

Aerial view of model (above)

Plan (left)

Elevations and sections (below)

Images from competition boards ©Ministry of Education and Culture

The Decision

The discussion went on for 22 hours, but the jury could not come to an agreement on a first prize. At least three of the political appointees would have had to agree with a potential common front by the six architects; but that never happened. In fact, agreement was not possible even among the professionals. Apparently, no less than four irreconcilable positions emerged, each defended by a group within the jury. In the end, after lengthy discussions, a compromise solution was reached: the first prize would not be awarded, only the two distinctions. Each group then abandoned their obstinate defense of their candidate, and the jury could concentrate on awarding the ‘distinctions.’ The amount originally intended for the first prize was distributed equally among the two distinctions, on top of the amount set by the rules. This was viewed from the outside as a signal from the jury that there would be no turning back.

The Minister of Education and Culture, who likely could have brought about a consensus, reportedly ‘remained very quiet during the discussions.’ Perhaps she was uncomfortable with a competition her Ministry had inherited from her Socialist predecessor, particularly at a time when, du to statewide budget restrictions, there are no public funds available for the project. Actually, the jury was reminded during their discussions that the competition had been organized by the previous Socialist administration. Possibly the new Conservative government prefers to have free reign to operate in their own best interests. Awarding a first prize would have been legally binding on the Ministry; so either the winning architects would have had to be commissioned within two years in order to proceed, or he/she would be entitled to a damage payment of 5M pesetas (US$40,000).

The Ministry explained to the media that “none of the proposals solved the Museum’s problems regarding the expansion of the exhibition spaces an public services.” She argued that this was only an ideas competition, that the problems to address were very complex, that the rules had been established by the prior Socialist administration, and that there had never been a commitment to accept any of the ten selected proposals as the basis for a future design. The Undersecretary of the Ministry of Culture stated that even if “none of the proposals solved the complex requirements and problems, they now had many usable concepts.” The President of the Prado’s Board of Trustees explained that they “had learned a lot,” and that “the jury’s discussion had been lively, intense, and intelligent.” In spite of the fact that the competition “had helped us in understanding better thePrado’s problems and the way to solve them,? He regretted that “no proposal correctly address all the functional, urban and architectural issues.”

Duro, already ex-president of the UIA, but still a member of the jury, said it had been a “sensible, sound, and serious decision.” Botta declared that the jury “was unable to find a brilliant idea” among the ten proposals.

Finalist

Rafael Moneo

Madrid, Spain

Sixth place in the semi-final round (7 votes) – tied with Marco and Pardo

Moneo ‘takes over’ the nearby convent by means of a bridge-building over the Prado’s back street. This building houses the entry hall and the restoration workshops, leaving an open public space on each side. Very respectful of the rules, and banking on an economical approach, Moneo’s proposal leaves the current museum building practically intact and concentrates on the new buildings located at its back, used for temporary exhibitions and museum offices.

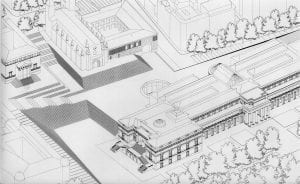

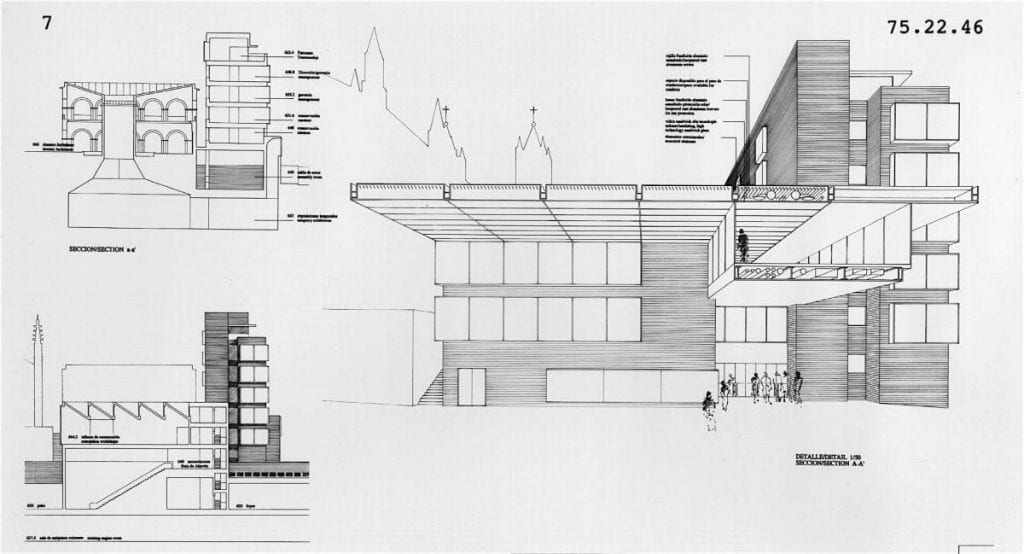

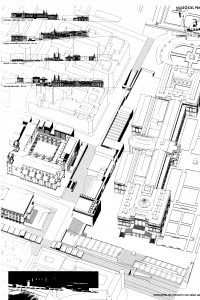

Model (left)

Competition boards (below)

Images ©Ministry of Education and Culture

Justification and Reaction

All submitted entries have been shown in Madrid only, at a rather desolate public exhibition space, which lasted just two weeks, as if the whole initiative had been something shameful, to be buried as soon as possible. At the exhibition’s opening, the ten finalist teams were given the opportunity to explain their proposals to an audience of architecture students, something they never had a chance to do in front of the jury.

A catalogue featuring the entries was hastily printed, as if a means to give some satisfaction to all the participants. The catalogue, contrary to what is conventionally done in such cases, does not include any text, rules of the competition, minutes of the jury’s sessions, no jury comments on the selected proposals, no registration lists, nor even an alphabetical index so a particular entry can be located on one of the 327 pages.

“Incredible, sad, extremely disappointing, frustrating and surprising” were some of the cautious qualifiers that the ten finalist teams used when referring to the jury’s decision. And learning about it through the media certainly did not make them feel any better. They found it hard to believe that none of the ten proposals were good enough to serve as the point of departure for a final design solution. Others were much harsher in their comments. The president of Madrid’s Architectural Association said that the competition results were “a collective fraud.” On Botta’s comments, a very respected Spanish architect and critic said that what the museum needed were not brilliant ideas, but ideas which were sound, sensible, balanced and, if possible, beautiful. When asked by the press, famous architects and museum experts used words such as ‘outrageous,’ ‘dismal,’ ‘frustrating,’ ‘ludicrous,’ ‘disreputable,’ ‘blunder,’ ‘incomprehensible,’ and ‘nonsense.’ Except for government media, no positive statement on the competition has been forthcoming.

Finalist

Antonio Barrionuevo

Sevilla, Spain

Third place in the semi-final round (10 votes)

The old museum building is devoted exclusively to exhibitions, while a new glass building i attached to it back facade. This structure houses the new entrance hall, and provides a link towards the old convent grounds, where most of the new program is located within a new service wing. Underground passages link the various buildings in the complex. -MR

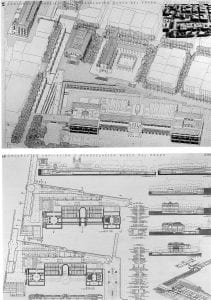

Model (above)

Competition board (left)

Images: ©Museum of Education and Culture

Some media reports referred to persistent rumors about supposed external pressures on the jury, or that the rules had not been respected by the organizers, or that some proposals that had been submitted outside the competition’s framework were unduly taken under consideration, or that somebody wante to give a chance to some architect who had not registered on time. The choice of the UIA to provide technical assistance in the organization of the competition had been criticized from the beginning, as this body was seen as ‘bureaucratic,’ ‘aloof,’ ‘too distant from the problem at hand to be able to be really useful,’ and ‘not knowledgeable of the Prado’s situation, Madrid’s context and Spain’s idiosyncrasies.’ After the jury’s decision was announced, criticism against the UIA intensified, especially regarding the choice of the jurors and the ‘hands-off’ policy the body followed once the process had been set in motion.

The competition rules were severely criticized from the beginning, and even moreso after the jury’s decision. The most significant single aspect of the rules was their request from each participant a decision on the philosophy and basic exhibition principles of the Prado collection—usually a task for museum specialists for a museum of this size and category. This circumstance would be the seed of the eventual calamity, as the museum’s administrators disagreed with the exhibition principles adopted by all ten finalist architects. Most likely, this could have been avoided if the program had been clearer and more specific to the Prado’s needs as perceived by those who were in charge of it. Also, the ten finalists expected that the jury would call on them to explain their entries in person, a notion that many architects and critics believe would have been in order, considering that there were only ten proposals up for review.

Architectural competitions in general, and large-scale international ones, in particular, have been questioned as an effective, efficient and fair system to select designers for a project, especially when the political factors are as important as they were in this case. Here, a clearer explanation of what really transpired was requested, but to no avail.

Finalist

Fernando Pardo

Madrid, Spain

Sixth place in the semi-final round (7 votes) – tied with Marco and Moneo

The New Prado is seen as a ‘campus,’ a cluster of several buildings with different sizes, functions and appearances. A new building is located at the back of the current museum, creating a new plaza and urban facade. This proposal places particular emphasis on natural lighting, as well as on the tectonics of the new structures, which have reminiscences of ‘soft-brutalism’ architects. -MR

Finalist

Enrique Zoido

Sevilla, Spain

Seventh place in the semi-final round (6 votes) -tied with Duerig and Rami

A new building is attached to the rear of the current museum, which will exclusively be devoted to exhibitions. Non-public areas and museum services are located on the convent’s ground nearby. The complex is all linked by pedestrian tunnels. -MR

Finalist

Dionisio Hernandez/Rafael Olalaquiga

Madrid, Spain

Fourth place at the first stage, first pass (9 votes)

The current building’s facades are left untouched, while a depressed courtyard, designed as a public garden, is built at its back. Around the courtyard a four-story underground structure houses the temporary exhibition halls, the cafeteria and personnel facilities. The underground connections between the various museum buildings is lit by oblong skylights, which function as urban design clements at the street level. -MR

Images: ©Museum of Education and Culture

Author Miguel Ruano has degrees in architecture from the Polytechnical University of Barcelona, M.I.T. and Harvard University. As a specialist in sustainability and the hospitality sector, he has been engaged as a consultant and in management for a number of high-profile, international companies, most notably in the U.K. He has taught in various capacities at a number of institutions, including the GSD at Harvard, M.I.T., University of Illinois, Washington University at St. Louis, and numerous institutions in Spain. He is the author of several books, and editor of the series, Design & Management and Architecture, and Design and Ecology (Gustavo Gili Publishers).