COMPETITIONS: Recent years have seen an exponential increase in invited competitions. You have been in several.Young architects are always asking, ‘How does one get shortlisted for an invited competition? Any advice?

ROB QUIGLEY: It would appear that firms get shortlisted based on the work they have accomplished to date. I’m not sure it’s anythihng you can actually promote, other than focussing on doing good work. Of course that takes time and doesn’t help the young firms—the reason they are entering competitions is that they don’t have the built work yet. So it’s a classical chicken and egg situation. That’s why I’m glad there are still open competitions, which don’t discriminate against firms which don’t have a substantial repetoire of built work.

COMPETITIONS: There have been a few isolated cases where firms invited themselves into an invited competition and won. One case which comes to mind was a high-rise competitiion in Miami, where Arquitectonica managed to become an add-on to an already shortlisted circle. After winning that one, there was no looking back.

RQ: I think the burden is really on the competition organizers. If I were organizing a competition and it was an invited format, I would hold at least one or even two slots that should be held open for young firms that have exhibited enormous talent, but don’t have that much built work to show for it.

COMPETITIONS: When a competition comes up, be it open or invited, what factors determine whether or not you will participate?

RQ: It would be unusual for us to get involved in an open competition. With invited competitions, it has a lot to do with timing.and the workload in the office. Secondly, we have to be interested academically in the issues. Sometimes the issues we are interested in are ones that we don’t have a lot of experience in. And that is what may be intriguing to us. Yet, we probably wouldn’t get invited into the competition unless we actually had experience in that building type.

A competition we are involved in now — a theater for a high school — is something we have never worked on before. We joined up with another firm on this, and it has been a delight dealing with this, mainly because it’s so fresh for us.

COMPETITIONS: After graduation from college, you went to Chile and worked on affordable housing. What effect did this have on your approach to the profession? Did it affect how you thought about architecture?

RQ: Did it ever! It changed my entire world view, including architecture. I was raised in an upper middle class family, spent my entire six years of college wholly focused on the world of art and architecture, like most students. You can’t get through unless you do. I grew up believing in certain value systems that had been taught to me to me throughout my schooling, about what America stands for —politically, culturally, etc. Suddenly I found myself in the middle of a Third World environment, where there was in fact a free election taking place. In fact, it was the most important election in the world at that particular time — the Allende election. We had a front row seat to this incredible political event. That combined with changing cultures — living in a small town at the edge of the Aricaen Desert, working together building houses where we would literally mix concrete with shovels; and what was so alarming was that I found out that we really weren’t the good guys. To a freshly minted college graduate, this was a shock. “We” were not helping anybody; in fact, we were making their life more difficult.

In terms of architecture, it was essentially a two-year architectural void. We were just building the most simple housing, dealing with fundamental social issues: How do you make a one-by-four beam hold up, and how do you get it to the site efficiently. There was no theoretical or intellectual discourse because of our isolation.

But during a discussion with a Chilean architect from the capital, he asked ‘Why aren’t there any American architects? This was 1969; so my answer was, ‘what are you talking about? What about Louis Kahn,’ who was certainly my hero at the time. He said, ‘He’s a European architect. He happens to be practicing in the U.S. Clearly he’s Eurocentric in his entire thought.’ He would give me Frank Lloyd Wright. Charles Moore was just beginning to become known in those years, and he would give me that. He wouldn’t give me Saarinen or any of those others: They were all Europeans.

He had a good point, which was that American architects were not really focussing on who they really are. So when I came back, I was very interested in creating an architecture that spoke to whatever region I decided to live in and take into account the local history of the place, the local vernaculars. Regionalism describes it rather superficially. It is a much more emphathetic idea. That caused me to restudy architects such as Aalto or even Le Corbusier and realized that their best work came from being focused on regional issues, i.e., Aalto’s furniture. Although Aalto may have been creating furniture for global use, what he was really trying to do was figure out a way in Finland to make this wood work through these particular machines they had available.The idea that you can create a more meaningful and more universally valid architecture by being provincial was fascinating to me. So when I elected to come to San Diego, that became a focus whereby the building type is irrelavant. Had I not gone to South America for two years, I would not have gone in this direction. It totally transformed my viewpoint.

COMPETITIONS: As you look back, was there any particular project which marked a turning point in your career?

RQ: No. Many careers have hinged on competition-winning design or a major commision from a patron. It’s been very incremental. We started out doing very small remodels and houses, and I opened my practice way too early in my career. At one point, we wanted to work in the civic realm, because we were interested in social issues that housing was not engaged in. It took almost 15 years to make that transition from doing just residential to doing a combination of broader building types. Now, at 60, we are to the point where we can do a wide variety of work with credibility. But it took 35 years.

COMPETITIONS: You have designed many building types, from detached housing to libraries, transit centers, community centers and hotels. Do you approach all of these projects similarly, or do certain building types (or master plans) demand another process?

RQ: We do tend to work differently on different projects. It’s not so much the building type, as it is other circumstances. If it is an extremely controversial project, where neighbors don’t want a community center, etc., in their back yard, then there is a communication problem of disenfrancisement, we promote working in a workshop format—a very differeent way of designing, which we happen to enjoy a lot. We have found that it produces more, not less, cutting edge architecture. We actually get more artistic license. Although it’s a process we promote, it is more expensive, and often clients are not willing to do that. The would hold true, whether it was a housing project or a civic project. Other situations result in how situations are going in the office. I may work on one project more than another, depending on the talent in the office, my schedule, etc. In general, we do like to work collaboratively. The is not the kind of office where I have the sacrad hand, and everyone else bows down to it. It’s much more of an interactive process. Some projects are more interactive than others.

COMPETITIONS: When you do decide to enter a competition, to what extent is the rest of the office involved, and at what stage?

RQ: It depends on the competition. In this one that we are involved in now, I have two people involved, who have been there from the very beginning. We always put together a team at the start. I always stay involved. With an office of only thirteen people, At that scale, I can have hands-on involvement in every project. There is no middle management—just me and everybody else. It makes no difference how long they have worked here: Some people have worked here 27 years.

COMPETITIONS: Aside from publications, your works have been widely exhibited. Can you measure any kind of payoff here in terms of work?

RQ: I do remember early on, when we had not won many awards, that won a prestigeous architecture award for a mixed-use housing project in Los Angeles. I proudly called the developer, announcing that we had won the award, and this was met with silence. He said, ‘Oh God,’ don’t tell me. I’ve got an architectural award winner? We’re going to lose our ass. The last time I won an award, I lost so much money, you can’t believe it. Here I thought it was a simple straightforward building, Rob, and now you tell me it’s an award-winner?’ So it’s double-edged.

The publications and awards are helpful in attracting talent to the office, not necessarily clients. The is true especially in the residential sector. But in the civic arena it is different—they do help there. We have probably won almost 60 design awards, but only done a few competitions, none of which have been built.

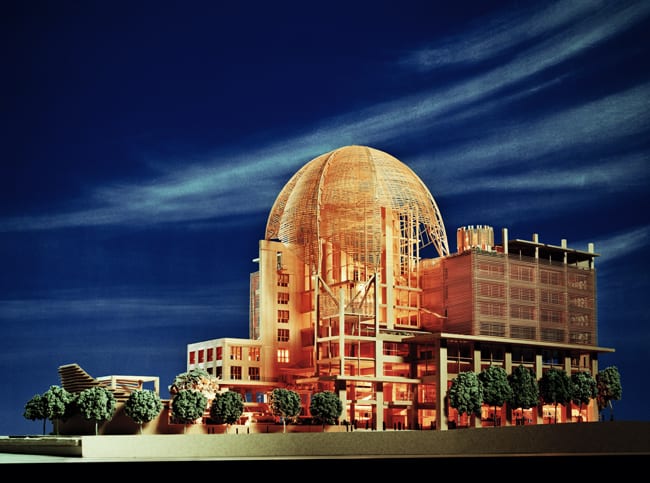

San Diego Central Library, model (2005); completion (2014) Rooftop terrace

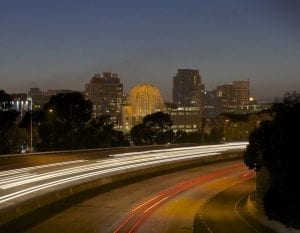

View to library at night from expressway

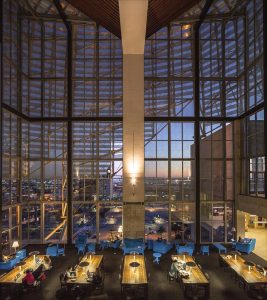

Reading room (left); View to library from street (right) Images: courtesy Rob Wellington Quigley

COMPETITIONS: You did win the San Diego Waterfront competition. And the future of that may be hanging in the balance.

RQ: The first phase is going ahead. That’s the rehabilitation of the old police station, which they were going to tear down. A temporary park will be created there.

COMPETITIONS: With the exception of corporate structures, most architecture on the west coast and southwest uses a different language from the rest of the country. Some architects from the west have been successful in overcoming this stereotype and break into other markets, often with the help of competitions, like Antoine Predock, Konig-Eisenberg, just to name a few. MRY had the early advantage of having Charles Moore’s name attached to the firm when they got their break. Are architects working on the west coast at a significant disadvantage when competing in the global market?

RQ: I never felt it was a disadvantage. When I say we’re interested in regional attitude, I mean the locale where that building is going. It’s not the signature of the region I’m so interested in, it’s the problem-solving process, the place-making in particular. We have a building in Colorado which looks like it should be in Colorado. We have had an office in the (San Francisco) Bay area for the past ten years doing work in northern California. I’ve never felt that we’ve been stigmatized because of those concerns. I think that people from other regions can look at what we have done in San Diego or in Phoenix or Colorado and see that we’ve adapted appropriately to those conditions. I think that is because we have never been interested in developing a polished signature…like a Richard Meier signature. Otherwise, how do you remain true to the ideals of place-making?

West Valley Library, San Jose, CA

RQ: One of the lessons is to respond appropriately. The educational system is all geared toward making foreground buildings, as is the competition proecess. Certainly that is appropriate in many cases—our library is a foreground building—but that is a minority of the buildings. What we have lost is the ability to make background buildings, make buildings that are more anonymous and yet make more profound connections, buildings that knit things together, rather than celebrate an iconographic quality. Students are wholly unprepared to accomplish that—it’s more difficult to make a background building than a foreground building—but have no training whatsoever in that area and don’t even think of it in terms of values. The thought hasn’t even occurred to most of the students you talk to that a decision has to be made as to whether a building is a foreground or background building, then respond appropriately.

COMPETITIONS: But a background building can have a personality also.

RQ: Of course. A background building can be just as rich as a foreground building. I like to think that we are creating one of our first background buildings, which is now under construction at UCSD (University of California, San Diego). It’s a student services building which is 100,000 SF. It is intentionally desgined to connect things together, not to draw attention to itself as an object.

COMPETITIONS: Back in 1984 you were honored with an award “as the best of a new generation who are changing America.” The past 20 years may have been a little sobering: what role can the architect play in society?

RQ: Architects can have very little influence over the changes which need to happen in this country. I can only speak from a local viewpoint, but architects can make a difference in their cities. For instance, in San Diego we’ve had an impact on planning decisions and our attitudes as to how the city is made. On a local level architects can help to educate neighborhood and civic groups to understand how things can be made better, and what an architect can contribute. We are in construction on a major homeless center in Palo Alto at the moment—a major contribution to the social structure of that community. And there were at least one or two young architects involved on the committee which initiated that project. They put together a coalition of service providers in the Bay area and privately raised $8M in six months.