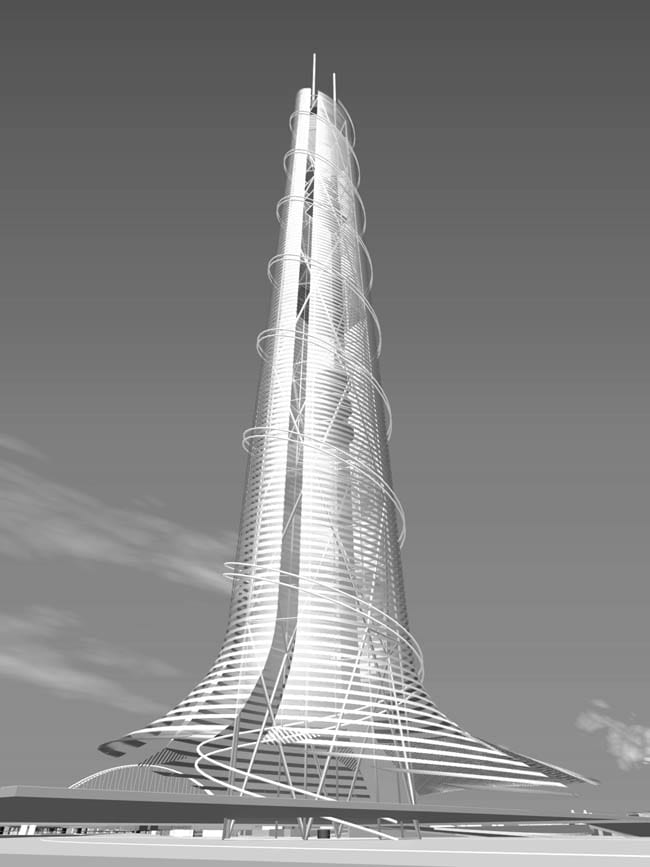

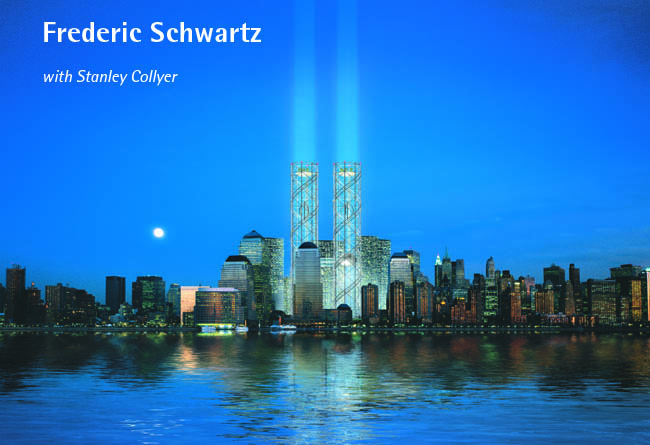

“World Cultural Center” – World Trade Center Innovative Masterplan – Runnerup, Ground Zero, NY, 2003

By THINK Team: Shigeru Ban, Frederic Schwartz, Ken Smith, Rafael Vinoly

FS: We are actually talking to some different firms about collaborating on a Toronto Waterfront urban design competition. I was asked there, how do you collaborate, why or why not, etc. Going back to Berkeley and Venturi Scott-Brown…at least at Berkeley you were taught, particularly from Escherick, Charles Moore and Donlyn Lyndon that architecture is a collaborative effort. It involves not only collaboration with other architectects, but also with landscape architects and artists. For example, Santa Fe (“Railyard Remake in Santa Fe, COMPETITIONS, Vol 12, #3) was a great collaboration where there were specifically architectural, landscape, and art components. What made that collaboration so fruitful is that we dropped all the titles: ‘I’m the artist, I’m the architect, landscape architect.’ When you bring in the different disciplines and different opinions, you get a much richer project, but also you are able to critique each other in a certain way. There is no set formula. Right now we are doing one in Patterson, New Jersey—The Patterson, New Jersey Masterplan—where we have two landscape architects, engineers, we have the second largest waterfall east of the Mississippi—it’s an amazing place, where Edison really started electricity. That collaboration, whether the participants are young, old, or experienced, all sit at the table and throw out ideas. The masterplan projects are like that, whereas the architecture ones—we have been doing that lately in San Francisco with HCD Architecture—are slightly different.

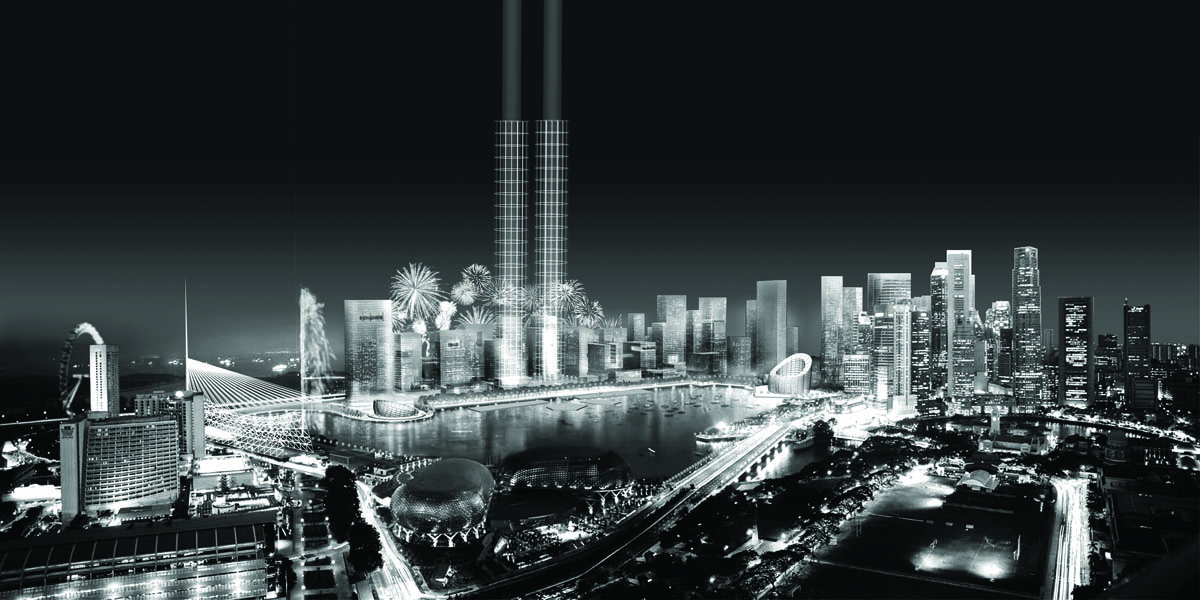

Real collaboration is about two different disciplines. For instance, George Hargreaves(landscape architecture) is downstairs, and we worked with him on this and on Singapore, also with Arup. Those roles are more defined. When it gets into two architects collaborating, where you have a good dialogue and respect for each other’s work and trust each other, it can make the work better than if it is one person.

The best recent example is the difference between the “Think Team,” where we were three architects, three engineers, and Ken Smith, versus Studio Libeskind. Can one person think that they have all the ability and knowledge to do not only to lay their hands on the masterplan, but do all the buildings, too? That is a complete misunderstanding of what That is a collaboration where we all made each other work better; we all respected each other; we all brought different things to the table, drew on certain philosophies that triggered the “Think” project—I brought my knowledge of New York and urbanism; Rafael brought all his brilliance. That had a certain chemistry that produced a work that would have been impossible for any one of us to do (on our own). Chemistry, trust, criticism happened in a collaboration in 1992 with Robert Venturi, Denise Scott-Brown and Steve Izenour. We did four competitions, one after the other—the Paris Civic Center in California, the Bronx Police Academy, the Staten Island Ferry Terminal which we won, and the Toulouse (France) project. Most competitions I do on my own; but I feel that two heads are better than one. But the masterplanning ones, and those on the other side of the world require people locally who understand the culture and the architecture. When we went to Shanghai, I got a crash course on Chinese architecture and Chinese landscape—driving me around different cities, and there is no way I could have understood Shanghai without working with somebody from Shanghai. It’s impossible to come in and just wave the wand. The landscape was what influenced our entry to the World Expo—based a lot on Chinese gardens and Chinese landscape paintings, how buildings are situated in the landscape, and making it green and possibly even more dense.

COMPETITIONS: One of your Ground Zero schemes had everything perched on a raised platform—similar to Citroyen Parc in Paris. Did that by any chance serve as a model for that concept?

The best example is still the Citroyen Parc, which is also a model for the High Line here in New York. The “Sky Park” took it to an extreme. We also did one, which we didn’t present, where it levitated thirty stories up—the program is like a pancake. You would come up in giant elevators. It is so high up that the land under it appears to be open. Alsop did that building in Toronto which levitates; but this one would levitate over sixteen acres.

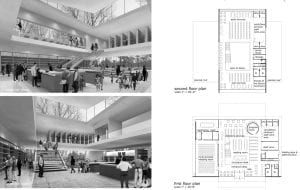

Nairobi Al Jamea Campus Competition Winning Entry (2013-2017)

FOXFowle Architects and Frederic Schwartz Architects (New York), Andropogon Associates Landscape Architecture

COMPETITIONS: It takes time(and money) to do a competition. Architects in large firms have controllers looking over their shoulders when it comes to deciding whether or not to do a competition. You do a lot of them. How do you decide whether or not to enter?

FS: I am asked that question quite often. I have a quick explanation: yes, you spend money to lose money. If you are watching the ticker, it’s hard to do these things. I follow a strategy: if you start too early, you lose your momentum and also a lot of money. I like to think about it for a while, then do it more like a charrette. Since the turn of the century, we usually have one in the office all the time. I do them because I feel it levels the playing field with firms that have controllers. I can compete for something big against somebody like SOM in a competition. I can’t compete against them in an interview process, because I’m not even going to get invited to the interview. I have gone up against SOM a few times in competitions and won, and my first job was at SOM. I’m able to do these large projects where I otherwise would not be considered—especially in America.

In Europe it’s a different situation, where all the public projects are competitions. The first competition in New York City in 100 years was the Staten Island Ferry Terminal. The last one was McKim Meade and White’s Municipal Building. I select a competition based on whether or not it is a design I usully would not have the opportunity to do. It also gives the young people in the firm a chance to work on interesting, and bigger things.

COMPETITIONS: Do you approach a competition like any other project in the office? How do you organize the office for a competition?

FS: It’s a volunteer system, where I ask ‘who wants to work on it.’ We have a very international office, about fifty percent from the outside—people from China, Germany, Denmark, etc. We put different people on different projects for different reasons. The kind of people I hire know when they come here that we are always going to do competitions, and they are interested in that. It’s part of the DNA of the office. You have to balance it with the work load, because it’s extra work. There are a couple here who work mostly on competitions. There is Jessica Jamroz, who is now running the New Jersey 9/11 Memorials – to be dedicated on September 11th. Both are collaborations with Arup, and it would have been impossible to do that without them.

There is great euphoria when you win—except zero on the 9/11 competition. There was nothing to really celebrate there. When you compete, you have to be prepared to lose. Some of them are just heart-breaking because you feel that everyone didn’t play by the rules, or what was the jury thinking?

FS: It was resolved by the brilliance of the fabricators and engineers in our office. We found a company that makes high-tech airplanes and stainless steel medical equipment, i.e., MRIs. For them to do this was just like regular work. It was like this: ‘Just give us the computer program, with the task of using half the the total weight of the stainless steel. When they figured out how to do that, the bids from the initial price dropped in half. By the time it is announced, the Federal Government will have announced an appropriation of half a million dollars.

COMPETITIONS: Many clients are curious as to whether or not a competition raises the quality of the project. From an architect’s standpoint, does it make any difference whether or not it is open or invited?

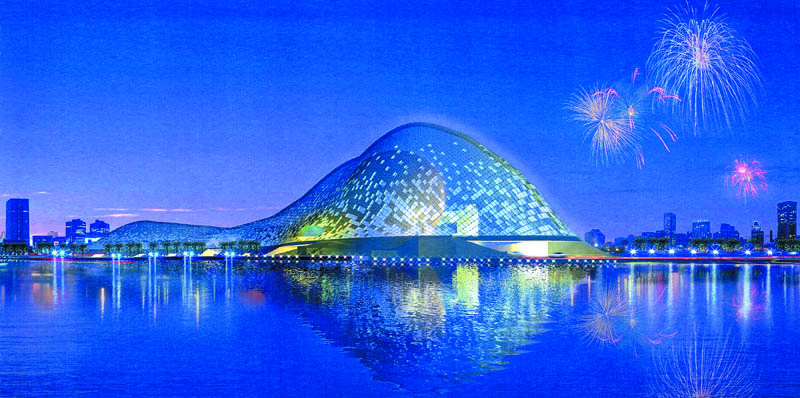

FS: There is a big difference between an open competition and an invited competition. With a competition, I am looking at a chance to expand our horizon and rethink the problem. One kind of disappointing one comes to mind—the San Diego Ball Park Competition. I liked the way it was set up, whereby in the interim, we met with some of the people who were making the decisions. Unfortunately, you’re not always seeing the jury; so your client leads you down a certain path and says, ‘That’s great;’ but then the jury can decide differently. We did something here that was extremely daring with Rafael Viñoly, “the wave.” All the other schemes were pretty conventional. It was hard to tell one from another. I think they all played it safe for the developer.

As for the question of whether or not a competition raises the design bar, I think that the very nature of the competition idea should open up the playing field.

COMPETITIONS: Are we placing too much emphasis on “signature” buildings? Should every young architect strive to be identified with a signature?

FS: I think not. It’s more important to do signature architecture than have signature architects. With signature architects, you know it’s that person’s building, almost wherever it goes, whereas a signature building is more specific to necessity. For instance, New York City needed the Chrysler building, the Empire State building, the World Trade Center, the Brooklyn Bridge, and Central Park. The collection of all of these memories makes our city what it is. I can’t really think of a signature building in Atlanta or Philadelphia. I don’t equate the Empire State or Chrysler buildings with a signature architect, although I know who designed them. Signature architects inspire young people to become architects.

The Shanghai project might have been a signature building; but it wouldn’t have been like, ‘I’m a signature architect. Already the Westchester memorial is being written about as the most important architecture in Westchester. And it’s not even architecture. I take great pride in what they mean. Seventy-five percent of those people (in Westchester County) don’t have a grave they can visit from 9/11. They don’t want to go to Ground Zero, they want something closer to home. So it acts as a de facto grave, because it is a gathering place for their loved ones. This design came more out of Escherick and Berkeley rather than Harvard, where each problem is faced anew. It’s non-judgemental architecture.