COMPETITIONS: Pursuing architecture as a profession apparently was not a foregone conclusion for either one of you when you began your college educations. It was somewhat of a winding road for both of you. Although industrial design and fine arts are not that far removed from the workings and aesthetics of architecture, it evidently took some time before you both decided to pursue it as a profession.

Ming Fung: I was always interested in the arts and in theater. Also, my background in anthropology led me to have a strong interest in how people live in a space. That interest in theater has always been in the background, in the work Craig and I do.

COMPETITIONS: It has occurred to me that students studying architecture should be required to take a course in set design.

CH: We both press for that in our individual schools.

MF: Set design and theater lighting. Architects often don’t know how to light a building, and theater really sets the mood. There is a lot to learn from that.

CH: It can get over amplified to the point where your design becomes so particular in trying to control what people feel—which is inappropriate in an architectural framework.

COMPETITIONS: Craig, you were working in Stirling’s office before he became a star. What led you to that office, what was it like in those days, and what did you take from that experience?

COMPETITIONS: You both have held teaching positions at universities throughout your careers. How has that contributed to your development as an architect?

MF: I think the education of architects has changed. When I was teaching, ten or fifteen years ago, you have students who were very daring. They kept you on your toes with everything you asked of them. That was a constant reminder of staying fresh. Now the students don’t challenge us much—maybe it’s because I’m getting older. It seems that they want you to give them the solution. What I’ve learned from teaching is how culture evolves, and how society evolves. I see a young student coming in, how they’ve changed, whether it’s through the computer, how it makes things easier for them. It’s kind of a barometer of things. Then it informs as to how you practice, how you design and how you read design.

CH: I actually feel more adventurous in myself than I see in most of the students. It didn’t use to be like that. I would echo Ming in that people seem to be more reliant on the beaten path.

COMPETITIONS: Is it different here than in Europe in that respect?

CH: I suspect it is. What you can do in a teaching format—it’s the reason so many of us do it—is that you can experiment with different ideas and see what the implications are. Last year Ming and I were in Shenzhen at a conference where the Chinese government is exploring the idea: ‘What is a creative city.’ The first thing I wanted to do was get back to my studio at UCLA and get the students to start exploring in physical terms.

COMPETITIONS: What is the most important piece of advice you pass on to your students?

CH: Put yourself at risk, because school is the most permissive thing they are ever going to find. They are going to run into a stone wall as soon as they graduate. So it they don’t use that time to reach out, explore, and take risks, they may never find out who they really are. The big crossover point for me—and I relate a little to students because of it—I was initially kind of a kid musician, classically trained. I found myself admiring Miles Davis, Ornette Coleman, John Coletrain, etc. My classical training has somehow never enabled me to get past that to become a jazz musician, because I had been trained in a very rigid way. So I had to switch fields to experience Miles Davis, etc. Since education is a kind of orthodoxy, by training they might not ever find out who they really are, because they are always working within that box.

COMPETITIONS: Competitions are just part of the competitive environment. Since competitions are basically a speculative exercise, how do you decide whether or not to participate—aside from the time factor.

MF: The time factor! That’s probably why we don’t participate that often.

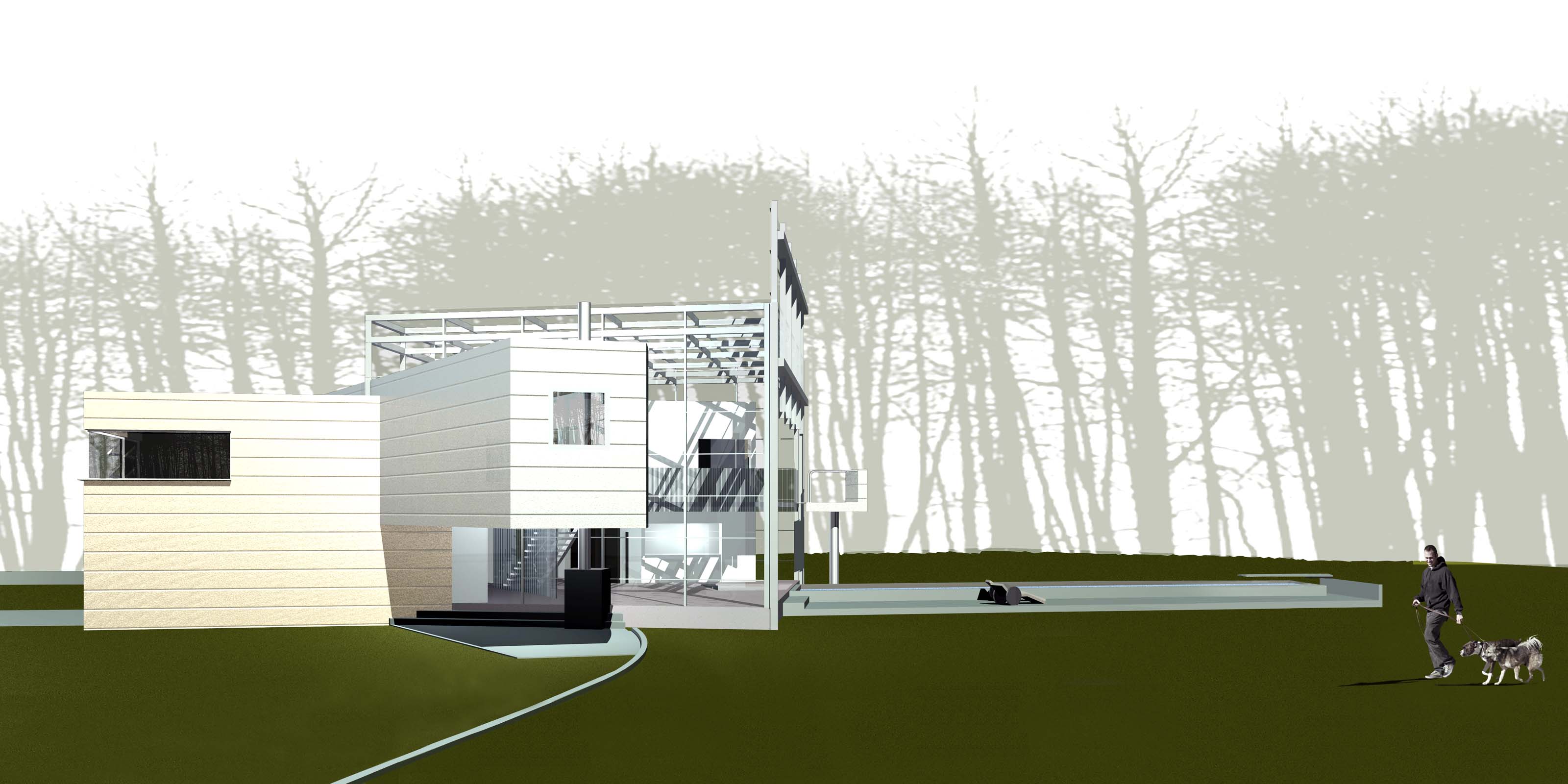

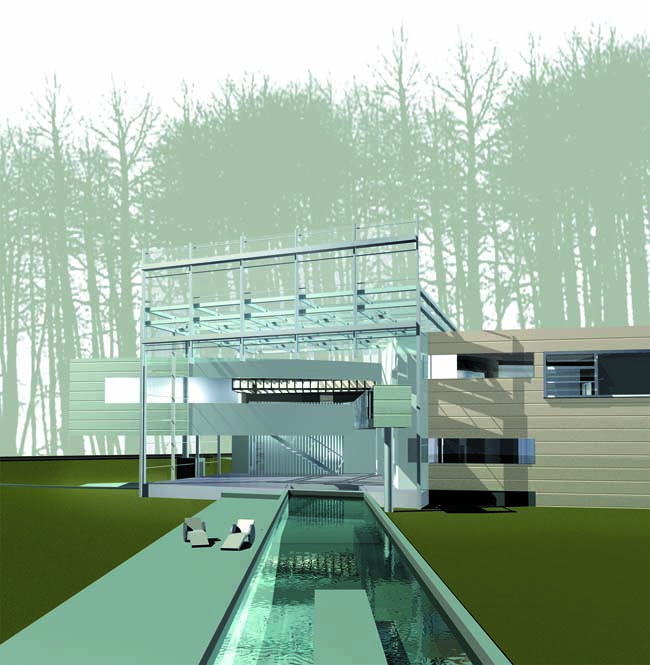

CH: Part of that is whether or not it allows you to take some unusual risks—in a framework which is rewarding because you set aside this time and your energy to take a risk and to grow and explore some things that would normally not be on your plate. I don’t think it’s necessarily about generating business; it’s an outrageous amount of effort with a very small possibility of achieving your goal. What motivates us to do a competition is to explore ideas we usually wouldn’t explore and to expand our design vocabulary. We were highly motivated by the Motown and Bethlehem Steel competitions. Those seemed to be places where we had never been before.

MF: One of the main reasons we would do a competition would be because of expressing ideas where we know that we don’t have interaction with the client. When we look at a competition, it’s not about winning; but the motivation is that we want to express those ideas whether we win or not.

CH: If anything, we tend to listen very carefully to our clients. There is a dynamic to that, but every once in a while you want to find out where you are, as opposed to where you and the client wind up. Competitions give you that opportunity. It’s allowed us to grow conceptually enormously through the years.

COMPETITIONS: Do both of you usually work on a new competition together, or does one of you—possibly being very enthusiastic about it—take it on individually? How do you decide on the team in the office, or does everyone take part?

MF: When we do a competition, I think the entire office works on it, because our office is not that big. We organize it in a way so that we can pull people from other projects the final two weeks. There is so much intensity with a competition, that everyone not involved would feel left out if they were left out.

COMPETITIONS: Do you restrict the time you spend on a competition?

MF: One way of looking at it in terms of when we have to begin working on it. To that extent time is restricted. Very often when we receive a competition bid, we don’t necessarily have the time to begin right away. Sometimes they give your two months, and we may not get started until a month or six weeks later.

CH: Some of it has to do with available resources, some with Murphy’s law. The impact on the office is an incredibly motivating force. I’ve often wondered why there is a different mindset working on a competition than when we work on a normal project? Part of it at least is that the totality of the effort is to get a high degree of definition around a fresh idea quickly.

From a teaching point of view—this was when Adele (Naude Santos) and I were trying to get San Diego started—the impact of taking a week off and having the whole school charrette on something has a sort of similar impact on students.

COMPETITIONS: There is a lot of collaboration these days in the world of architecture and planning (Even Frank Gehry has had to admit to that now). If the demands of a project/competition require a large team, it is only logical to seek out those you have worked with before. How about collaborations where outside architects sought you out?

CH: We just finished a competition about three weeks ago for an exhibition on “Mars” at the Chicago Science Museum. The kind of collaboration which is kind of jazz bandy is where everybody is playing different instruments and having really strong inputs.

MF: We first look at how team members can complement each other in terms of expertise. The riskiest situation is when we have to go outside of our circle that we have worked with. What I like about it is that it’s a really good test of how you are going to be able to work with these people; if it’s like oil and water while your are doing the competition…. We always look at collaboration in architecture as similar to playing music.

CH: We are not looking for a top down thing where an engineer does his salute and does what you tell him. We are really looking for more complex ideas. Some of those may come more in the exhibit framework, rather than in the architectural framework, where the exchanges are on many planes, as opposed to where the mechanical systems should go. In the case of RfPs (Requests for Proposals), the choices tend to be highly political. We were on the runner-up team for the Grand Avenue project, which was won by Morphosis. They got rid of Morphosis and Frank Gehry is doing it. That is another big difference between a competition and an RfP process, where you think, ‘we better have that civic engineer he’s hooked into the politics. This really pollutes the stream, and you don’t really get an ensemble of people who are creatively linked.

COMPETITIONS: Your newest project is the Linda Lea Theater. What kind of process took place for you to get that commission?

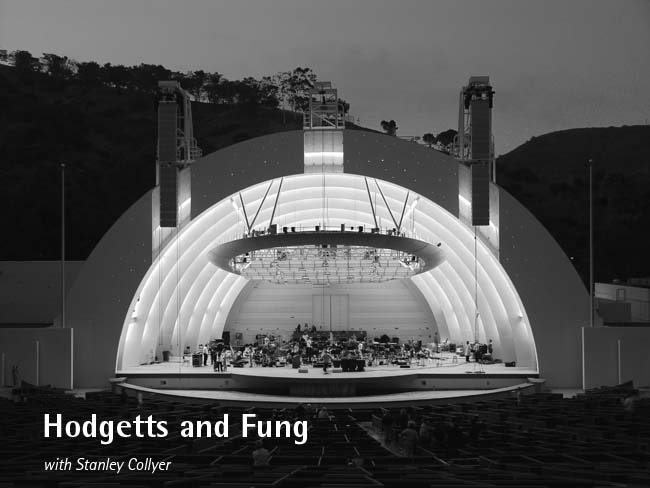

COMPETITIONS: Now the Menlo Park – Atherton High School PAC competition went well for you. Aside from the fact that you won, what were your impressions of that competition?

CH: Did anyone mention to you how our hearts sank when we walked into the room and saw these incredible renderings (by Predock).

MF: We love his work.

COMPETITIONS: The jury thought that the Predock design would bust the budget.

MF: I think the jury in this case was very reasonable. Most often in competitions, architects are selected based on the renderings; and then in development, the design has to be changed. In this competition—and it was kind of unusual—we were lucky that the jury was very pragmatic and were able to have a real discussion as to whether this can be accomplished within the budget or not.

CH: We had thought about it as a sort of pragmatic thing. Actually we did not have a clue as to Menlo’s affluence. We kept asking ourselves, ‘this is a high school, a very modest project; we were puzzled by the fact that they were having a competition. So we addressed this as a wayward commission. So it was a very practical, pragmatic approach. So it was lucky to have a jury which was also in that realm.

COMPETITIONS: As a young architect, Craig, you did a city plan for the Venice Biennale. Has the passage of time and living in southern California changed your ideas about cities since then?

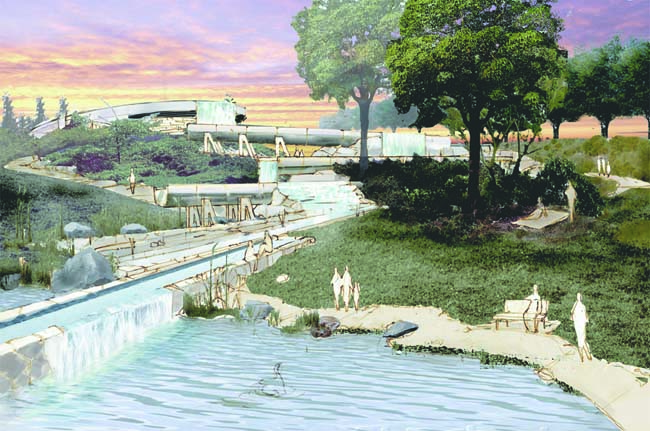

CH: I have to say with some sense of successful prognostication, that that entire plan was based upon the idea of working at home, working on computers, mixing manufacturing and residential areas with the ascendancy of clean technology, and about lifestyle enclaves. I was right. I wouldn’t change a thing. Very recently we have been working here on a project for magnetic levitation transportation in Las Vegas. One of the things that the developers were beginning to have a sense for was that a transportation system needed to be more than a utility; it needed to be a pleasurable and entertaining experience. That’s why they called us. So this is part of that curve which everybody thought was ridiculous at the time. The things we have thought all along were important in architecture are now becoming more and more accessible. Every day you now hear about people working remotely from the office. This is why we were never terribly interested in traditional commercial architecture. Both of us feel that it’s time has passed.

MF: We were interested in the idea of recycling buildings and adapting buildings of an entire district. When we were doing an exhibition for the Milan Triennale which was called Identity and Difference (The Imageries of Difference. The Triennale in the City), where we were thinking of cities as enclaves with that lifestyle. Milan in this sense is not any different from Los Angeles. There’s an entire industrial area where the artists start moving in, much like in LA. Even in China and Taiwan, they are going through this type of renovation, where the art district has become an ‘in place’ to be. In Taiwan, where there was this old train station, really only a shed, the architecture school took it over and made an annex out of it. This has drawn the artist community to the area. Even in Beijing the arts district is catching on, much like SoHo.