COMPETITIONS: You started out as an art major. When did you decide to move to architecture?

Peter Pfau: I went to art school, dropped out, and became a carpenter and contractor. Going back to study architecture was kind of a natural progression for me. But I spent time getting back there, because I had to go through various colleges to get to the point where I had a degree.

COMPETITIONS: Being in construction isn’t a disadvantage before going into architecture.

PF: It isn’t, because I’m still a capable carpenter; so I expect from people in the field what I know I could deliver myself.

COMPETITIONS: In New York City you worked with some high profile architects who had relatively small studios. I’m thinking of Susanna Torre. Did those experiences serve as a model for your own firm?

PF: I also worked with Michael Schwarting at the Design Collaborative in New York. We won a PA Award for the FIT (Fashion Institute of Technology). It was a great time to be in New York where there were a bunch of interesting people. For Susanna I actually worked on a Fire Station in Columbus, Indiana.

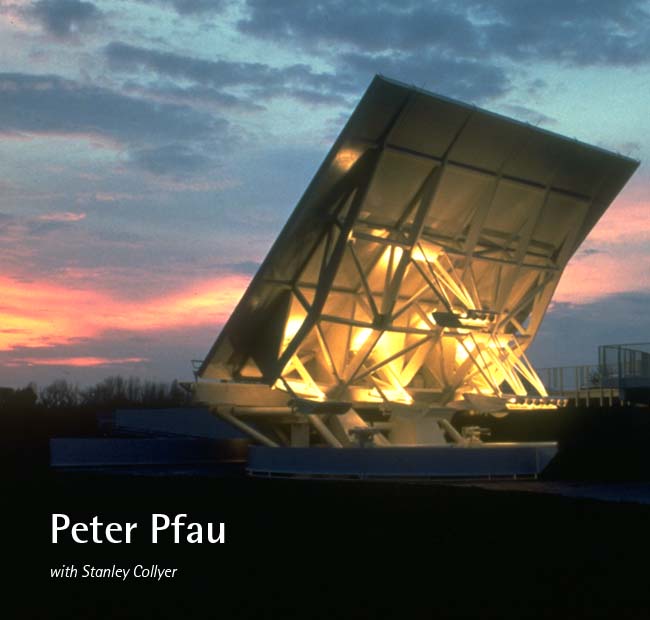

COMPETITIONS: One might have thought that winning a high profile competition like the Astronauts Memorial Competition would have led to bigger and better things. Was that the case with this one?

PF: Absolutely. We got a lot of notoriety as a firm back then. My partners, Wes Jones, Paul Holt and Mark Hinshaw and I experienced a crazy time: we were working 14 hours a day, seven days a week. What we learned was that just being a flavor of the moment, hot firm, does not get you work. You need to have references and a track record. We would get up for some of these interviews; ‘but here come these young bucks with no experience,’ and they would say, ‘Are we going to hire those guys, or the others who have already done five of those which we are doing?’ That is the challenge that everyone has to overcome in their careers, convincing people who are going to spend a lot of their hard-earned money on a project—that they should hire you. At that time I was 35 years old and barely had any idea what I was doing running a firm. It (Astronauts Memorial) was an exciting time and a pretty amazing project where nothing like it had ever been done before. We had to find engineers who could do dynamic engineering. It was quite a challenge.

COMPETITIONS: Were there any second thoughts about the siting of that project? Some have remarked that it deserves a more secluded location, so as not to compete with the main attraction.

PF: Funny you should ask. Wes and I felt very strongly that it should be located across the road, because it was too close to the ‘main event.’ But there were a number of reasons: it had to do with the telemetry path from the control buildings to the launch pad and other factors. The last thing we wanted to do was have the memorial, which memorializes disasters, resulting in a disaster because of bad telemetry. It didn’t really give us a great deal of choice; but I think we made the best of it.

COMPETITIONS: Holt Hinshaw Pfau Jones wasn’t exactly a gigantic firm, but not small either. I notice that you struck out on your own during that downturn in architecture activity in the early 90s. What was it like to start up a firm under those conditions?

PF: If you can survive in a downturn, you can survive under any conditions. We always keep a wary eye towards what is happening economically, to go into a survival mode if necessary. We’ve been fortunate to have worked through all the ups and downs—and be able to do good work.

COMPETITIONS: What advice would you give to young architects who want to open their own office?

PF: It ain’t pretty. It’s a very difficult profession, and I ventured into it as a very young principal out of blissful naiveté and passion for the activity of making architecture. It’s become a profession that’s very much driven by the proclivity for litigation in the marketplace. It’s changed from a profession where McKim Meade and White used to do about six drawings for the Lowe Library at Columbia University. To do a building like that now would mean to have 350-400 sheets in our drawing set. And then there is the expectation of tremendous expertise, which far exceeds what is humanly possible for even the brightest of human beings. So we end up with these armies of specialists on our teams. Somehow, I think expectations for the level of perfection of working drawings have come out of that in a way that contractors are relying more and more on greater levels of information from the architect. It’s problematic, because you can’t answer all the questions. We are only human. It’s a tough business out there, and everyone is quick to blame the architect. So my one piece of advice to a young architect is, not to distinguish by whether or not they make mistakes, but by the elegance by which they make them when they repair them.

COMPETITIONS: These days we hear a lot of talk about prototype schools. But intercity schools don’t often fit into that category. Lick-Wilmerding is a prime example. Aren’t these problems more interesting to solve?

PF: They are. But the reality is that the fee structures of most public schools are not manageable for us. So (there) we can’t do the kind of work we do, which is very design and research intensive, for the kind of fees you get for doing a public school. Unfortunately, we’re not able to do the type, unless there is some kind of climatic change that’s looking for a higher level of design. We’re realistic about that; we try to make sure that we’re doing work where people are actually looking for what it is we do. It’s a very challenging type—you would have to set up a nonprofit or something to do that, and it would turn out to be a financial disaster anyway.

COMPETITIONS: Getting shortlisted for an invited competition is not easy. How did you manage to get shortlisted for Lick-Wilmerding, in view of the fact that you had not done much school architecture?

PF: It’s always a complicated dance. In that case, we evidently said the right things in our RfQ which led up to the shortlist. It’s taken us a long time to learn how to respond to those things in a meaningful way. It’s amazing how much work it takes to get work.

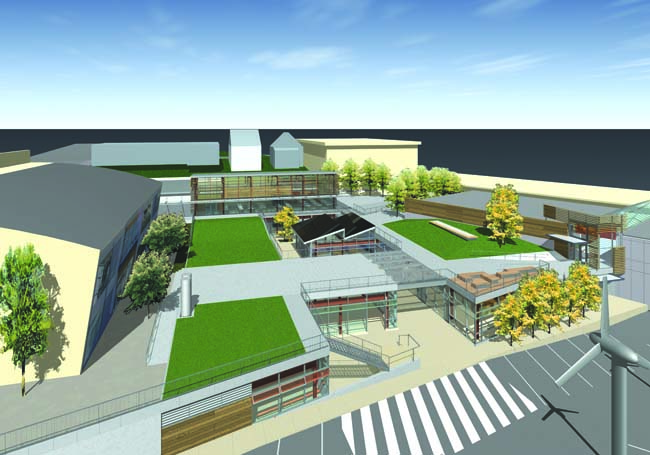

COMPETITIONS: Going below grade at LW for the shop areas obviously won the competition for you. It now seems so logical. Was this solution an instant revelation? What was the gestation of that scheme?

PF: I collaborate closely with Dwight Long on all the designs we do here. One of the things that distinguished the competition was that we had an actual meeting with the client in the middle of the competition. I’m a strong advocate of this, because otherwise you are just shooting in the dark—you have no sense of what resonates with them as a group. Initially we decided to explore three different schemes. I can’t remember all the names we gave to those schemes, but one was ‘Getting in touch with your inner shop (Doing the coolest shop building you could imagine).’ I believe that Dwight hit upon the idea of the underground building. At first we were skeptical, because digging entailed a lot of expensive excavation. But the cost estimator we had on board did a quick estimate of our schemes. Because the cut was clean, and the underground scheme didn’t require an elevator, it very much simplified the plan and made it less expensive—It was counterintuitive to us.

Once we realized that, we were stoked. We then began to see that it created linkages with other things, and we could create a kind of precinct where all the classrooms could look on to each other and collaborate between the disciplines as opposed to being stacked on top of each other. We presented the three schemes, one of which was the underground scheme at mid-term. As outof- the-box thinking, it clearly resonated with them. With some of their input, it evolved into the final scheme. It was quite different from any of the other schemes. It’s one of those things where design is an exploratory process. It’s not like we’re so brilliant that it comes to us immediately: it comes to us through exploration and evaluation of alternatives and deep thought.

COMPETITIONS: How familiar were you with how the school worked previous to the competition. By creating grassy areas above ground, the hallway congestion problem was solved. Students now hang out outside and in the cafeteria. Could you have anticipated that?

PF: We poked around out there. One of our interests, which that project illustrates is how do you make all the places in between the places as interesting as the places you get to. We’re interested in what kids do, where do they go? How do they use the space? How can we design things that are about meaningful use? Sometimes they aren’t used quite the way we thought they would be used; but that’s interesting to me, as long as they are used. It’s all about how kids interact together, share knowledge, and create community. With each school, we immerse ourselves in the sociology and existing philosophies of each school.

COMPETITIONS: The Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Center, an infill which is so common in San Francisco, isn’t a terribly high profile foreground building. Was that intentional? As the first of its kind to be built in the U.S., did you consider providing it with any special type of visual image? Or was the functionality on the inside of primary importance to you?

PF: Our competition-winning scheme was about having a much higher profile image than we were able to realize under the reality of the challenging budget we had for the project. The original competition scheme that Jane Cee and I came up with was this idea of a flaming luminous beacon on Market Street that would be visible from farther away in the city, and would be a symbol of the heart of the gay community. The reality was that we had very challenging budgets and constraints to work with, so we had to come up with something that worked and went through five or six value engineering passes. It still has a little bit of energy with the color scheme, which is a little in-your-face.

When thinking about my progression as someone who does competitions, there’s a real difference between what I’ll do now, and what I would have done. When Wes and I were in New York together, before we came to California to join Holt Hinshaw Pfau Jones, we would do any competition. Any competition you sent to us, we would do it at night after our jobs. After we started HHPJ, we were doing almost any competition—aside from a competition for a classical city hall. Now I have a firm to run, and it costs a lot of money. It’s one thing when it’s my own selfsacrifice; but requesting a sacrifice of others is not fair if you don’t compensate them. When we do a competition now, we play for real, and it gets expensive. We get competitions where we get paid five grand and we spend $60K. It’s a big hit for the business to do that sort of thing. After doing so many of them over the years, we now try to be selective at trying ones we think we have a shot at—where the energy, alignment of the client and the project and our interests are in sync.

COMPETITIONS: The Berkeley Montessori School, with its covered walkways, has the feeling of a California mission enclosure. Was this the thought behind the plan? Or was it the practical demands of the program?

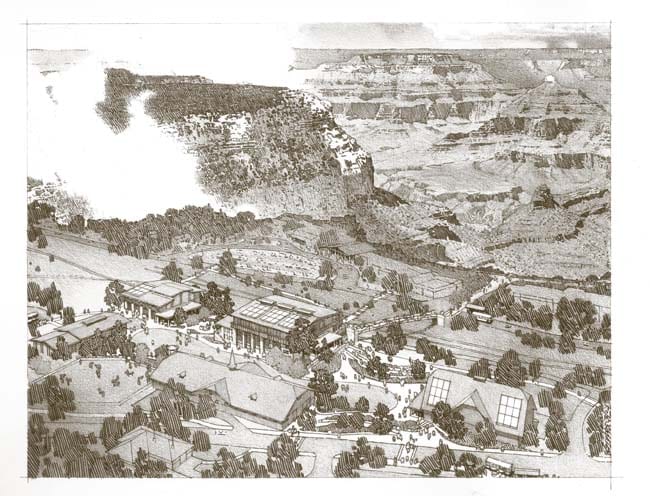

PF: There was the challenge of relating to what is clearly an odd centerpiece—the half-Moorish domes of that Santa Fe structure (railroad station), which was done by a Santa Fe staff architect. Oddly enough, I am working for the National Park Service on a building at the Grand Canyon that the same Santa Fe staff architect did. And it’s an equally interesting building. It was a significant, historic building; so we had to configure the new buildings around it in a way that they didn’t touch. So we hit on this idea of creating this inner court with meaningful spaces around it. Because it was a very challenging budget—we knew that from the beginning—our strategy was to make a very simple stucco box that would relate to the stucco of the historic building and attach a tame strip of architecture to it.

PF: The architect who designed the synagogue was an old friend, and we had a very meaningful dialogue with them. There is a great working relationship between the two: there is a memorandum of understanding where we create less parking between the two sites, because their use is different. The school needs parking until 3 pm, and they need parking from 4 pm on. So we were able to create an overlap of spaces.There is also a shared drop-off.

PF: A lot of public entities are wrestling with different delivery methodologies. So you will see a lot of design/build pairings. With the design/build pairing, you can do these things called best value analysis, where it is not necessarily price, but best value. We try to avoid situations where the outcome will be

bad, especially if I get up in the morning and come into work facing bad outcomes and a building you aren’t proud of. You can see that there are a lot of institutional clients who are endeavoring to prevent the low-bid outcome, because it’s pretty much universally awful.

We can’t draw enough drawings to enforce a low-bid situation to have a good outcome. The day is long, and there is a lot of opportunity for wiggling and putting bad work, being reluctant about taking it out to replacing it with good work. So we just end up remodeling the deviations from our drawings to get a project that looks like what we want it to look like. That should be avoided. Our profession is challenged, and I wonder whether we shouldn’t be looking to a European model. They care more about design.

COMPETITIONS: Which projects are you working on presently?

PF: Some green designs—the San Francisco Friends School, and a new classroom building at City College which is a green building.

COMPETITIONS: The City College project is a public entity.

PF: In that case there was a real motivation for green design and a good quality of design. That made for a good situation for us. We are also doing a private school in Oakland and Sacred Heart schools where we are just completing their master plan and a field house. The highest profile project we have in the office at the moment is the SPUR Urban Center, located on Mission Street. It’s a little like the Urban Center in New York, with a focus on research and planning.