|

|

|

COMPETITIONS: Since you are interested in planning and ‘The City of the Future,’ one might imagine that someplace like the United States, where a building is here today and gone tomorrow, orr entire districts for that matter, would be more fertile ground for you, rather than Italy, where city cores are eternally preserved. How can one understand the ‘City of the Future’ here, against the background of Italian urban tradition?

Franco Purini: In Italy many think that the problems of the future in our country can be resolved only within the framework of preservation and restoration. Therefore, many think that we have enough (large) cities, where it is only necessary for them to deal with their own evolutionary process, taking into consideration their own history. As a result, the ‘Italian culture,’ not the ‘architectural culture,’ the culture that expresses the essence of the country, has a tendency to belive that something new is in someway an accessory, a corrective or an improvement, something marginal. To them, what is important is the presence of antiquity.

I have found this vision very limiting and restrictive, because even if Italy has a great presence of historical evidence, it also has a great need to have a strong tie with contemporary thought. Therefor it is necessary to add to the framework of that patrimonial conservation the politics and the implementation of new available knowledge, new strategies where needed. That should provide a relationship between our country’s ideas and contemporary global development.

What is the effect of the current politics of preservation? The core or center of the historical city, like Sienna, is perfectly preserved as well as can be expected; and granting that such a thing is possible, this city expands without any planning, creating a suburban area. Therefore cities like Sienna, Pisa, and Venice just to name a few, have horrendous suburbs. it would be much more interesting to preserve the historical centers for what they are, and then the new districts which are needed should be built according to a well coordinated design, just as if they were new cities or neighborhoods as part of that existing city.

In Italy today, especially in the north, the diffused city prevails, a variety of the American sprawl, so that in the end there is no more an identity to these places. There aren’t any places, there is nothing!

COMPETITIONS: In China, for instance, they are building many cities next to old ones, for as many as 50,000 inhabitants.

FP: Yes, they are building many cities and this is because there is an enormous growth and an enormous shift of demographics from the country to the city. That is slightly different from Italy, because here the process really happened in the 50s. Today we need small cities, where the creative class can live and work (according to the American sociologist Richard Florida), a class that is characterized by talent, technical knowledge and tolerance, while it is globally connected.

This class of citizens is able to make connections that are cognitive and existential, which was not possible earlier. For instance, people who work in the economy but also in communications have very strong cultural needs, such as museums. They also have physical and spiritual needs, so they require spirtiual places or something analogous that have great relationship to the body – health, fitness, nature, which are to be accompanied by a sustainable environment; and therefore ecology comes as a natural preoccupation – it is not a 9/11 emergency call to the immediate needs of people, but a new way of conceptualizing a new, profound and deep rapport with the world. This new reality has been accepted in Italy as well, where new ways of expressing these ideals should be met.

The old cities cannot provide much help, because they speak of other values, having been created in a very different time. For that reason they are based on another type of existence.

COMPETITIONS: In the U.S., in places like Naples, Florida, we are being forced to build affordable housing for school teachers, who otherwise could not afford to move to those cities because of the cost of living.

FP: In Italy things are a bit different. Things in the workplace are more traditional as opposed to America where continuous changes in the workplace and social mobility are the norm. So in America you have a situation which doesn’t exist here. But in Italy, especially in the north, there are cities capable of doing similar experiments to the U.S. and can support these changes or adjustments almost without any government support. This class is accustomed to live in very modern homes and they have a high level of consumerism. They are very mobile and dominate their territory. They hold tickets to the global economy; but unfortunately don’t have the wherewithal to realize their full potential since the town environment that could support these possibilities and ideas is missing.

COMPETITIONS: A number of Italian architects have influenced 20th century architecture in America, such as Scarpa and Aldo Rossi. The postmodern movement in America can hardly be imagined without the Italians. Still, that proved to be a short episode in architectural history. Is there a discernable trend towards a modern vernacular now? When students come back from there travels, what are they talking about?

FP: Let us say that foreign students coming here are not very interested in modern Italian architecture. It’s very rare that they look up Moretti and others, unless they are truly well prepared in advance.

Meanwhile the historical Itailian architecture is of interest to all foreign students. Modern contemporary Italian architecture, because of its strong political implications attached to architectural ideology, is of interest only to the more sophisticated; it is almost for experts. Unless you talk about Scarpa or Rossi.

There are three instances of this modern relationship between today’s American architects and Italian architecture. We have Robert Venturi, who wrtoe Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. He was strongly influenced by the perception of Rome’s traditional architecture and its baroque period – and by relatively unknown architects like Armando Brassini.

Then there is Peter Eisenman, who studied extensively the work of Giussepe Terragni, which was fundamental to his formative years. He considers himself very Terragnian.

There is also Steven Holl, for whom the experience of contemporary Italian architecture was veyr important. His first projects were influenced very much by the Italian Rationalism, above all by the projects built in Italy in the early 70s. His projects were published in pamphlet architecture. Let us say, that for the educated, sophisticated architect of the present, modern architecture is very important.

For the everyday architect, contemporary Italian architecture is not interesting, just the historical genre. The contrary is true for Italian architects, who are very interested in contemporary American architecture; but they are less knowledgable about Richardson, Olmsted, or Sullivan.

COMPETITIONS: You are part of the neo-rationalist movemnet in Italy. Some foreign architects, such as Kleihues used that term to describe their approach to design. What do Italians understand “rationalism” to mean, and how did aesthetics fit into this?

FP: I knew Kleihues well and also Ungers. Rationalism or neo-rationalism is essentially a sort of temporal transformation of classicism. Its foundation is classical, meaning that classicism is that system of rules capable through compositional means of extracting order from chaos. Rationalism is to an extent a new manifestation of classicism. A system that can unite in a made-up combination, order and chaos. Italian classicism has always had some nuances, where some traces of the chaotic state that preceded the final stages of that new order are visible. It is different from English classicism in that it is more mechanical and repetitive. For us, it is very important that the form be clear, but also mysterious. In this, we are followers of Tafuri.

COMPETITIONS: In Italy, there is a lot of what we call paper architecture, simply because many competition-winning designs are never built. On the other hand, there are a number of excellent publications in this country which can bring these designs to the light of day. In the U.S. it’s very important to be published – it can mean jobs. How important can winning a competition be here, even if it isn’t built?

FP: Until a few years ago, it was difficult to build in Italy, but today, things are changing. Even so, an enormous number of architects are entering competitions in Italy. Many architects never build anything, because as a profession in Italy, we lack power. For instance, architects are limited, subject to intimidation: “If you don’t do it this way for me, I’ll get somebody else to do it.” Government officials here don’t consider architecture to be an intellectual pursuit. Architects are regarded almost as a blue collar worker that provides a service. Architecture is not regarded as a product of the mind. At the core of all this, there is a deep devaluation of the idea of architecture.

COMPETITIONS: Like in the U.S.A.?

FP: No, I don’t agree. I wouldn’t say so. In the United States a personality like Frank Gehry is encouraged to do his own architecture. He is sustained and supported. He is regarded as an important artist and the country is happy to have him as a citizen. In Italy a personality like Frank Gehry, who is into research, is culturally opposed in every way. Here he wouldn’t be considered reliable and trustworthy. In America he is entrusted with extraordinary jobs. This is unique!

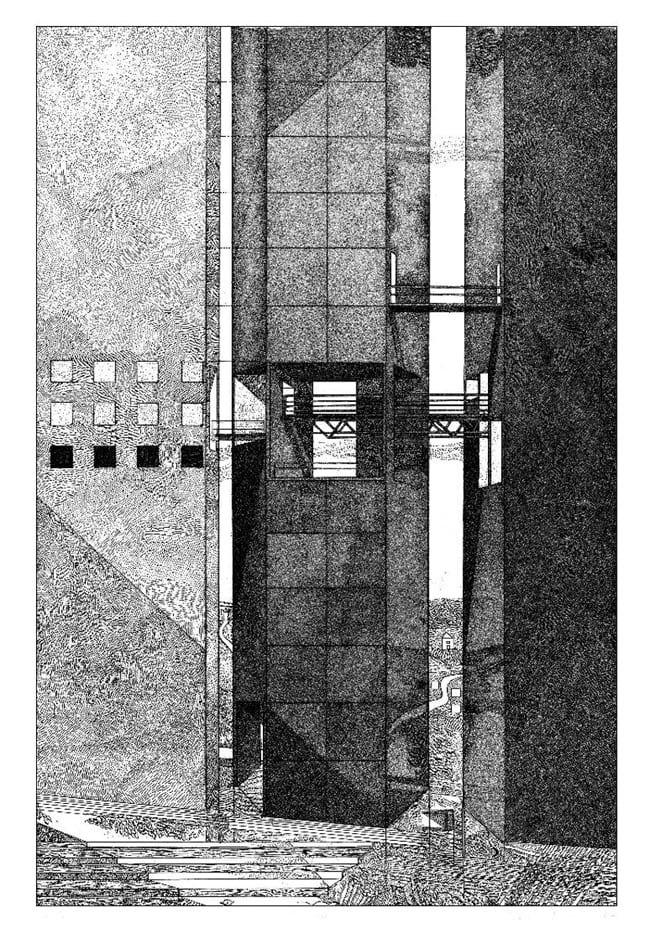

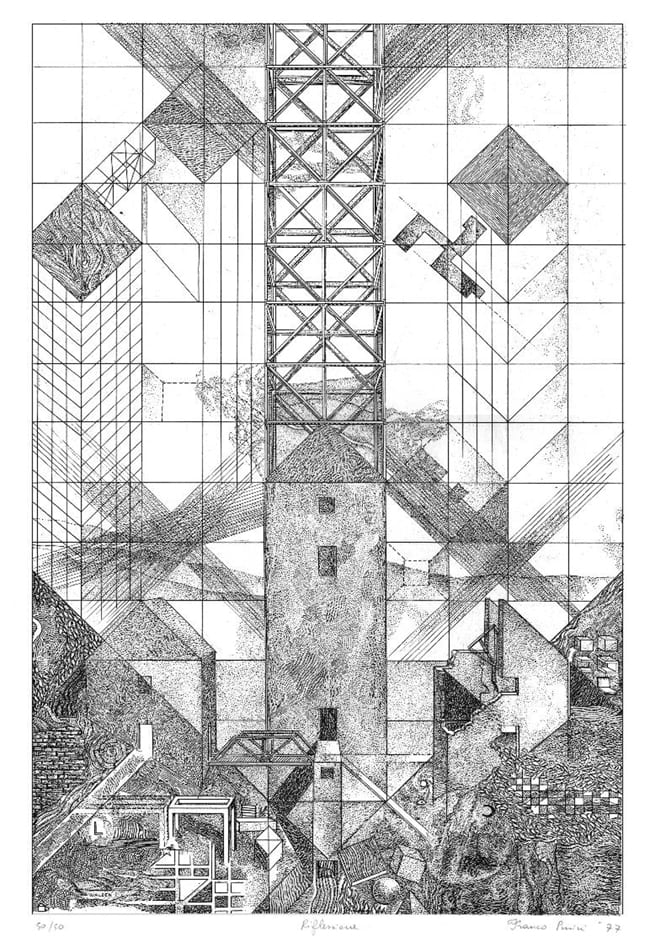

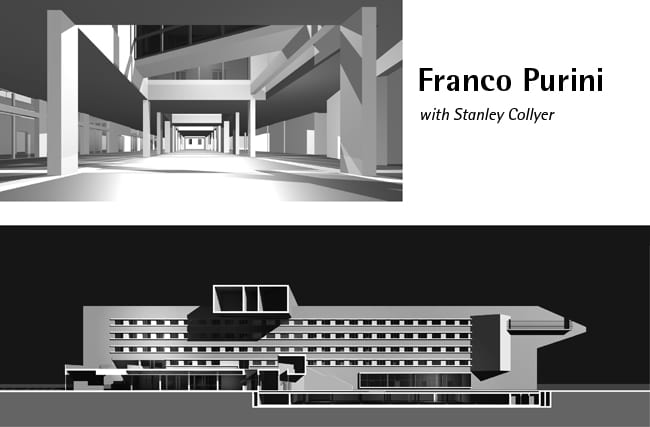

COMPETITIONS: Many of your drawings are in collectins around the world. With the advent of computer-aided design, how important is the hand rendering now? Doesn’t it still reveal a personality that a computer cannot replicate?