Oceanside High School has a location that many other big public campuses may envy. The 2,500-student school is an easy walk to some of California’s most beautiful beaches and also is close to the big open spaces of the U.S. Marines’ Camp Pendleton base along the Pacific coast. What’s more, the campus is just to the west of the Interstate 5, the main freeway route that puts downtown San Diego only about 40 minutes away.

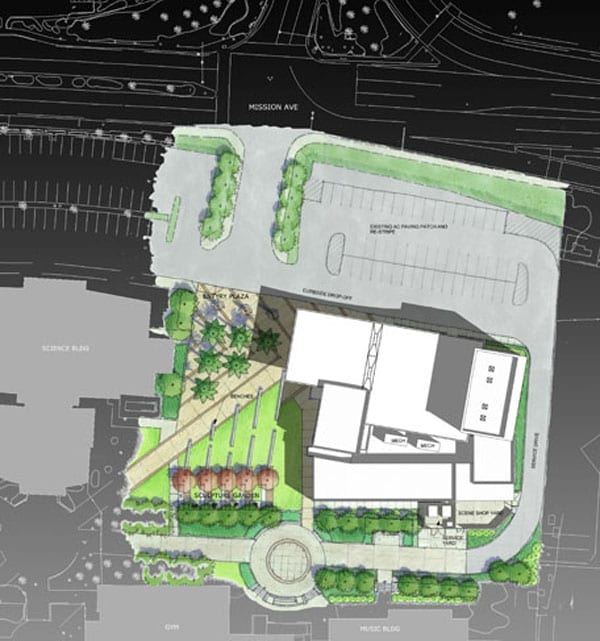

So when education officials in Oceanside decided that the school needed a new performing arts center, they knew they wanted to take advantage of the location and create a landmark that could be seen from the freeway. They also wanted a facility that would serve students taking part in drama, music and dance programs, as well as accommodate the wider San Diego County community who could attend professional shows there too. The school district figured that sponsoring an architectural competition for the first time might yield an array of designs to satisfy those demands and solve more practical questions of loading in theatrical scenery and helping students master the skills of digital lighting and sound production.

“We wanted an iconic building,” explained Larry Perondi, superintendent of the Oceanside Unified School District. “We wanted it to say that education and the arts are important but we also wanted people who come to Oceanside to say, “Wow, what is that? We felt our kids and community deserved to see what’s out there in terms of architectural thought and how we could get the best architectural bang for the buck.”

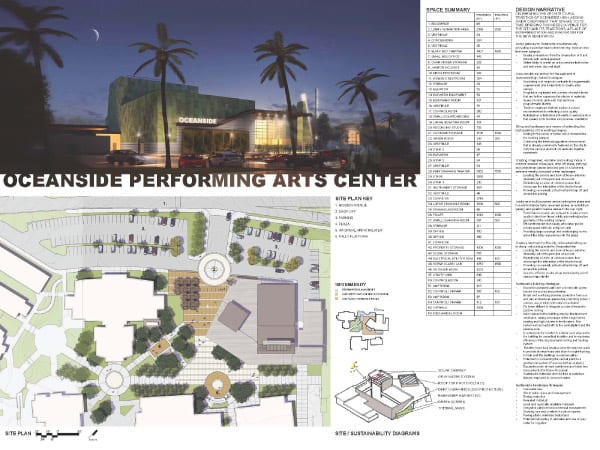

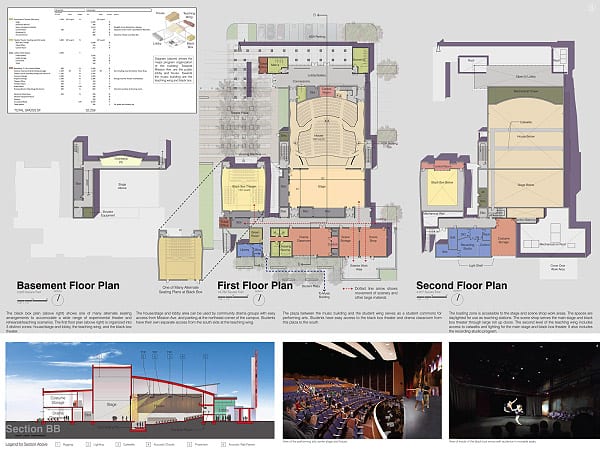

The program for the 20,500-square-foot arts complex included a 500-seat auditorium with a proscenium stage, fly loft, and band pit; a “black box” space that could hold 150 audience members for more experimental performances; and other indoor and outdoor spaces for meetings, galleries and classes. The district, in its documents, said it wanted a center “that nurtures proposed performing arts programs in a manner that meets their functional requirements, is adaptable for future needs, and becomes the defining element for its campus neighborhood and a signature entrance for the school.” And do all that within a $17 million budget.

The district advertised for interested firms and then interviewed eight of the 28 that responded. The list was cut late last year to five finalists, the latter having experience in theater and school design. Each received $10,000 for their designs in a process managed by architectural competition advisor Bill Liskamm. Those finalists, all with Southern California offices, were: Baker Nowicki Design Studio; BCA Architects; Harley Ellis Devereaux Architects; John Sergio Fisher and Associates; and Roesling Nakamura Terada Architects.

A six-member jury of design professionals, theater experts and school officials was formed to recommend a winner. Then, after a public display, the school board in late February affirmed the jury’s choice of Harley Ellis Devereaux.

There was spirited debate along the way, with pros and cons for all the proposals, according to Cheryl Gaston, a manager of the district’s bond construction for the school district. But in the end, the winner “best met the goals and objectives of the district.”

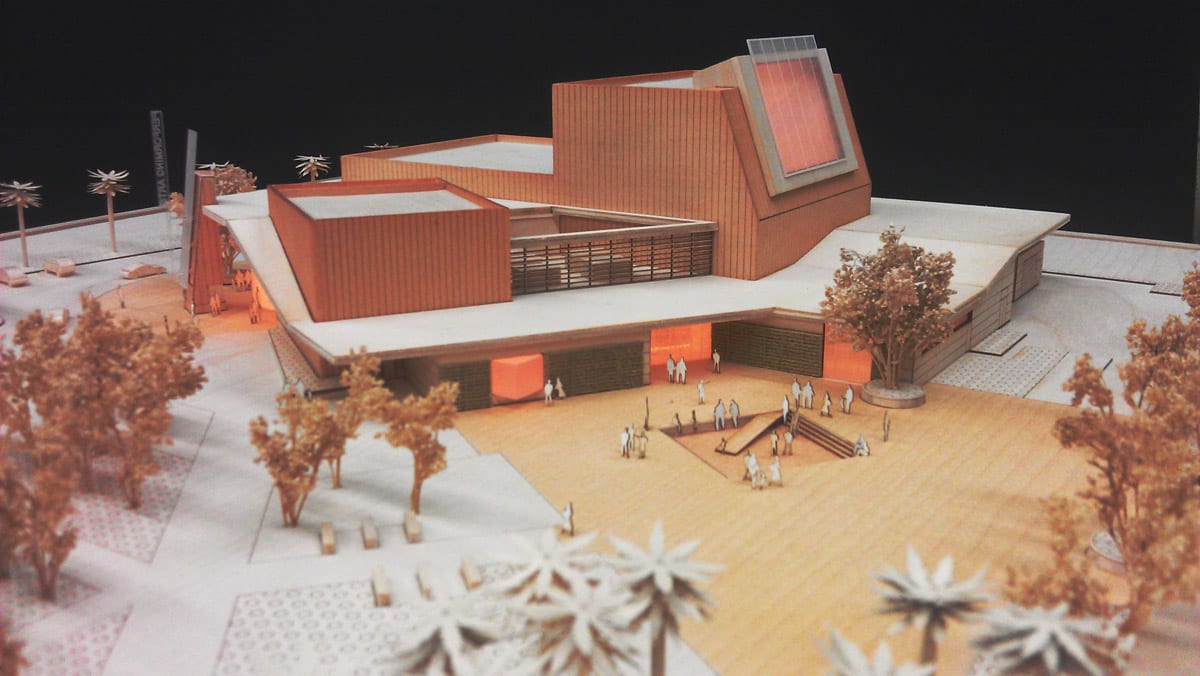

The Harley Ellis Devereaux proposal has a series of sculptural forms, with a higher boxy portion to accommodate stage apparatus. A common lobby links the large auditorium and the smaller performance space and the lobby can serve as a gallery or meeting room, with bands of digital “Times Square-is” announcements crossing the room. A separate obelisk-like tower for the box office is pierced by a roof extension from the main building, which also creates a sheltered walkway and canopy. The complex’s upper exterior is partly clad in copper panels, an unusual choice for a location that gets sea breezes.

Much of design focuses on “simple elemental forms” that would work both for students and for outreach to the community, said John Dale, principal at the firm. The goal was “timelessness and not something that was overly exuberant and unbuildable.” As for the copper, Dale described it as “a material that speaks to longevity” and yet would respond to the elements, turning green. (The school’s team colors are green and white.)

The most eye-grabbing element is a tower-like solar chimney for passive cooling and sunlight collection for electricity on the back of the proscenium. The chimney will be lit up at night with a massive video screen, providing an attraction visible from town and freeway. “It’s a kind of beacon, a very visual evidence of commitment to sustainability,” said Dale.

Presentation Boards by Harvey Devereaux – click to enlarge

The entry from Roesling Nakamura Terada Architects has a beveled wing-like roof line with skylight elements that bring sunshine into the complex and can be screened off during shows. The concrete block building is fronted by a glowing glass wall and, outside that, a pergola walkway of columns. Off to the side, a slim marquee tower of about 50 feet height can flash digital announcements to the world. Its two performance spaces are separated by an outdoor plaza, and student-oriented functions are in the back, in a two story wing. The black box can open to a grassy amphitheater.

“We wanted it to be grand but also wanted it to be on a human scale,” said Ralph Roesling, a firm principal. He said the building is partly inspired by the Irving Gill civic buildings in Oceanside, with “simple massings, simple volumes.” And when glowing at night through the glass frontage and flashing messages from its tower, the effect, he said, would be “very dramatic.”

Presentation Boards by Roesling Nakamura Terada Architects – click to enlarge

BCA Architects took their inspiration from the nearby ocean and beach, according to firm president Paul Bunton. Its curved, wavy roofs and a mesh screen wrapping the exterior like a ribbon picked up on the sense ocean waves. “That was a key theme,” he said. That sense of movement continued into the main hall, where curved sound baffles on the ceiling and angle walls give the impression of such motion.

Use of the outdoors was important in a California climate; so the plan called for an outdoor amphitheater on one of the complex and a small event park on the other. LED lights would be embedded in the mesh exterior to display images or announcements outside or for students to project their work in digital media arts; overall, the entire building would appear to glow from a distance. The firm’s proposal described it as “an iconic, landmark building that entertains and educates the students and the community, both day and night, inside and out.”

Renderings by BCA Architects – click to enlarge

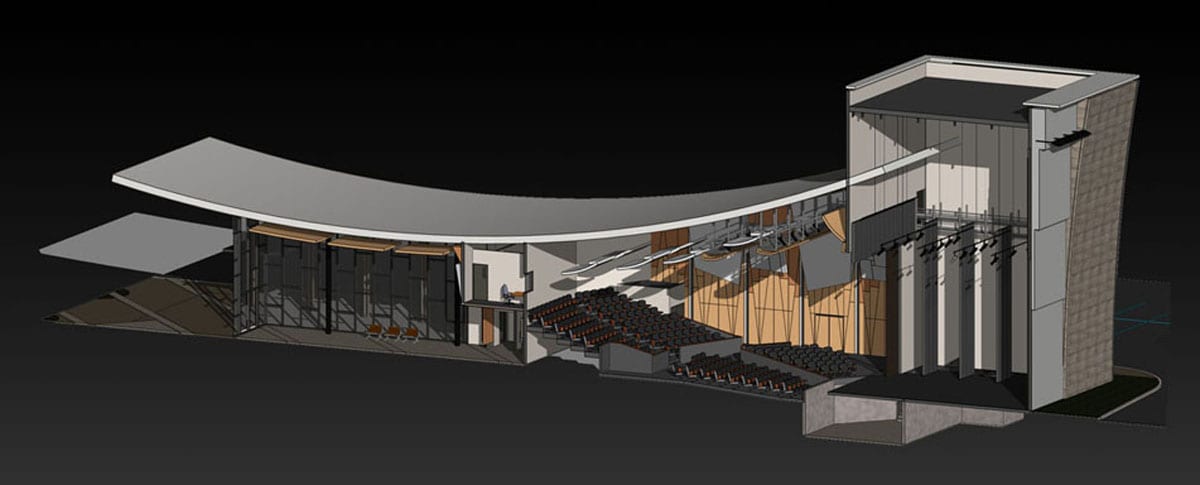

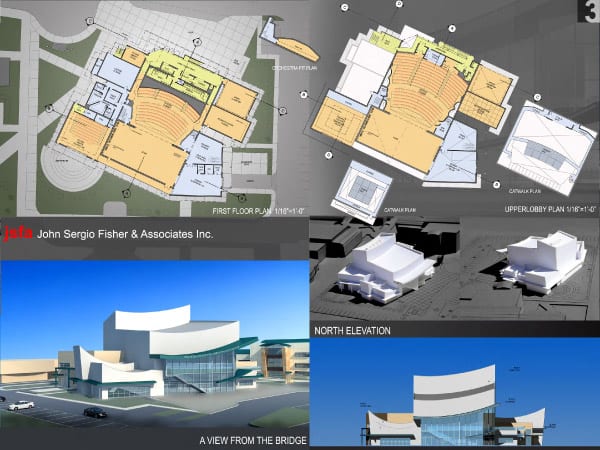

Much of the Fisher plan evolved from giving the main theater enough ceiling height and room volume to properly project the music of a full orchestra, according to principal John Sergio Fisher. The curved rooflines, inside and out, evoke a sweeping feeling but also help with the sound quality and eliminate the need for an acoustical ceiling cloud. “We were doing a performing arts center, not a high school auditorium,” he explained.

As a result, the building itself is a series of stepped-up massings with slanted rooflines. The stage loft, to the rear, is the highest point, and flanks of lower-scaled wings on the sides contain classrooms, sound studios, costume shop and the black box space. That flexible performance space can open up to the outdoors and an amphitheater. Much of the main structure’s public façade will be a two-story wall of glass and much of the rest would be masonry.

The Fisher entry did not include any of the towers or flashy projections some of its rivals had; instead it projects a more classical tone. Fisher said he hoped freeway drivers would notice the center but said he was “not as interested in impressing people driving by at 65 miles-per-hour for a few seconds” as he was in its effect on the high school campus and creating a “well-functioning and beautiful performing arts center.”

The most eye-catching part of the Baker Nowicki plan is a dramatically curved roof, like a ski jump from a tower structure for the back stage area down to a glass-line lobby, and then over to form a canopy. The back stage tower can be used to project digital imagery and lighting shows toward the freeway. Firm partner Jon Baker said the design recognized that many of Oceanside High’s campus buildings were mid-Century modern, and that he did not want a complete clash with them. His goal was: “something that had a certain amount of theatrical flair, but (something) we also felt would be compatible with the vocabulary of the existing campus. We did not want it to look like a spaceship landing from Mars.” The façade combines stone, tile, glass and plaster, materials that are durable for a high school and yet “provide the punch you want for the community.”

The Baker Nowicki design for the main auditorium differed from the other finalists in laying out some distinctly separate side sections of seats, slanted in their orientation, rather than the completely straight or gently curving rows of traditional Continental seating. Baker said the angled sections created “a little more creative atmosphere and changes the experience for patrons.” He also said it makes better use of the space for smaller meetings.

In the discussions among jurors and then among school board members, some of the plans were rejected for being overdesigned, too overpowering and not paying attention to the kind of war and tear, and potential vandalism, that can deface a high school facility. Some of the proposed lobbies were too small, and, according to jurors and officials, some entries did not pay enough attention to the classroom and teaching facilities.

Harley Ellis Devereaux won points for what superintendent Perondi called “its wow factor” of its solar chimney and digital projections, and its ability to be seen day and night from town and the freeway. The winner also was able to create a building that is comfortable for students yet has enough substance that “in ten years, people will say that’s a nice building.” He added that it was achieved without apparently busting the budget: the winning team “really listened to us and knew we are a public institution and not made of a zillion dollars.”

Overall, the plan “was well scaled and fit more comfortably into the site,” recalled juror Eric Davy, a San Diego architect. Its interior layout was appealing, particularly the usable lobby that linked the two performance spaces and provided more flexibility for various uses.

The copper cladding triggered some debate about its costs, its viability near the ocean and the likelihood of it becoming a graffiti target. But the copper would start relatively high above ground, about eight feet, and presumably out of reach of most vandals. And in the end, jurors decided that the copper contributed, Davy said, to “an impressive use of different materials, textures and colors that created more interest in the building than a couple of the others.”

For juror William Virchis, a veteran theater teacher and arts activist in the San Diego region, the winner combined an iconic presence with attention to function and long-term maintenance. For example, he said the design accommodated theater sets and orchestras while keeping in mind its use for students day to day. “Others didn’t seem very practical for instructional use,” he said.

More detailed design work and permitting are now underway, with groundbreaking expected in early 2014. Officials then estimate that construction will take about 18 months. The basic construction costs remain about $17 million but the overall price tag is expected to be about $23.2 million including equipment and costs for inspection and testing.

-Larry Gordon is a writer residing in Los Angeles