All photos courtesy of Catalogue des Concours Canadiens, L.E.A.P., Université de Montréal

The Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) made architectural history in 2010 by winning an open international competition for a new museum—in a place where international architects hadn’t won one for over fifty years. What’s more, they won in a city that’s been on the UNESCO World Heritage list since 1985. This aggressiveness in foreign markets is business-as-usual for the world’s top firms. But surprisingly, the competition wasn’t in China or Russia or India or Brazil, but rather Canada. OMA won the international competition for an addition to the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec (MNBAQ) in Québec City.

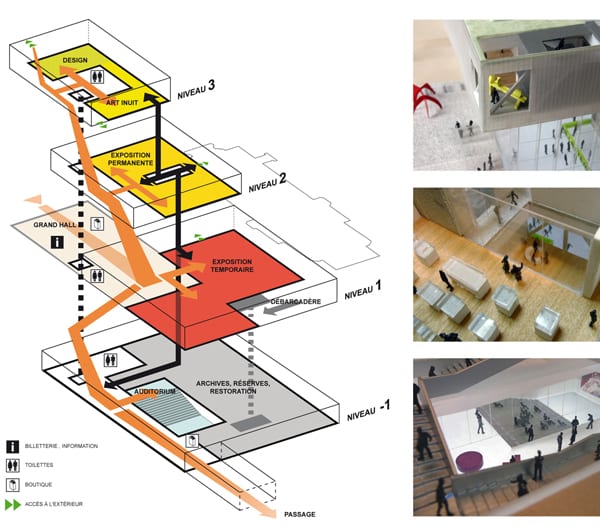

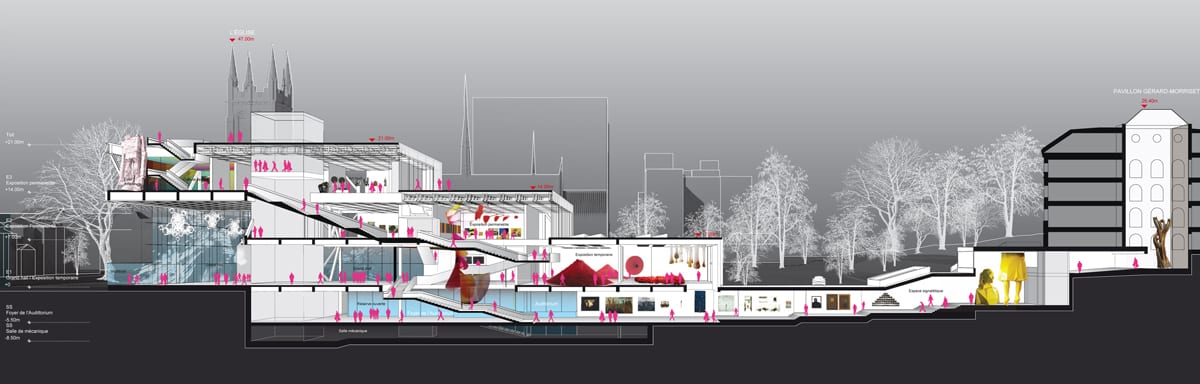

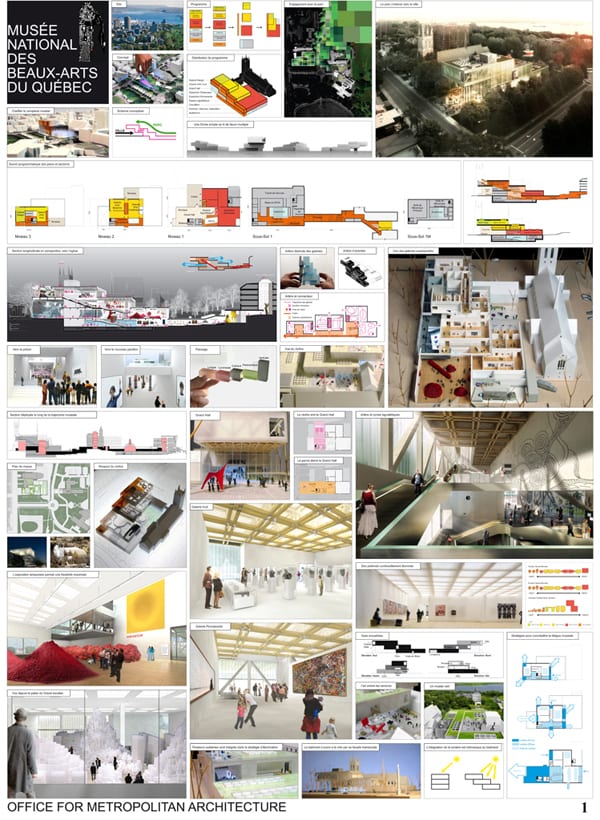

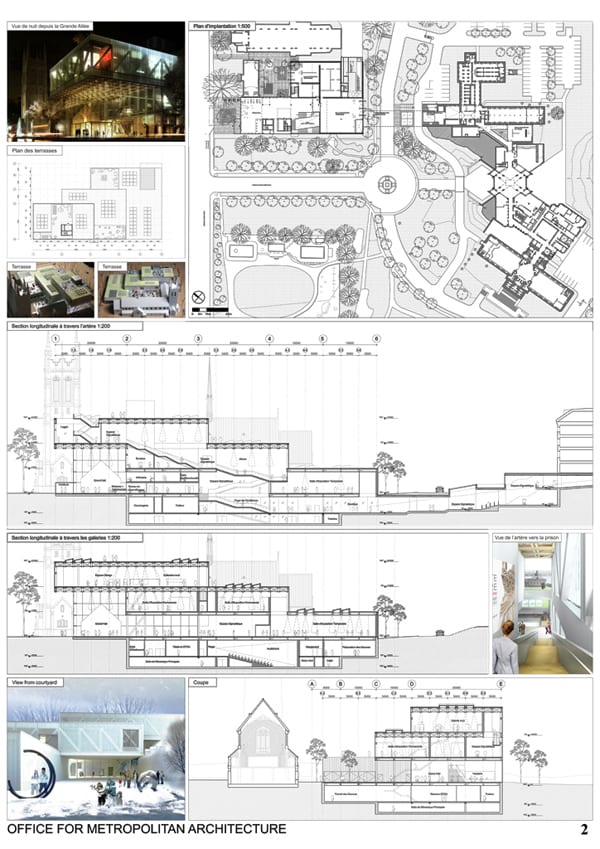

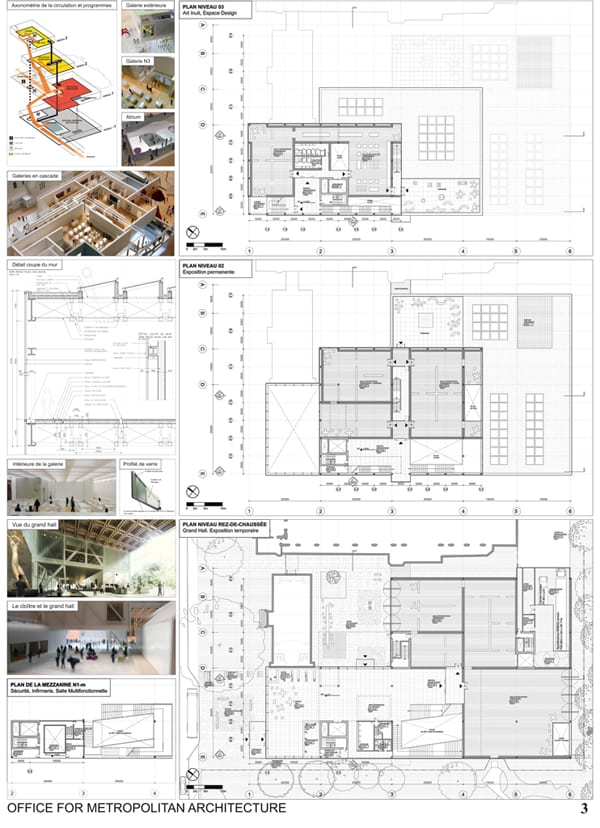

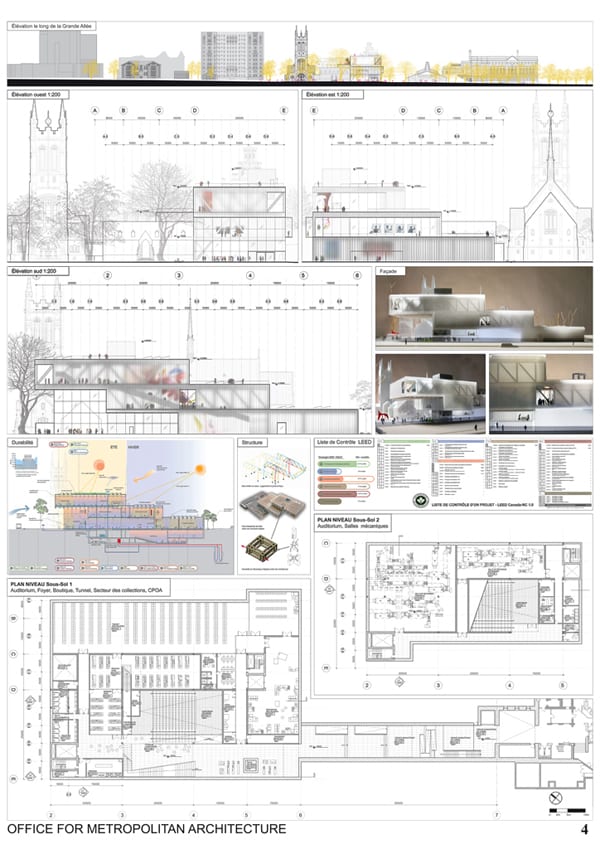

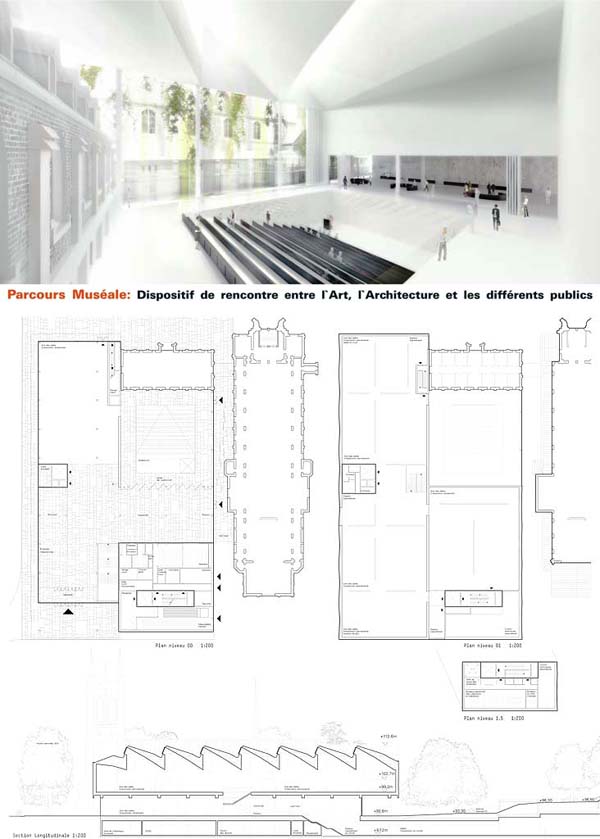

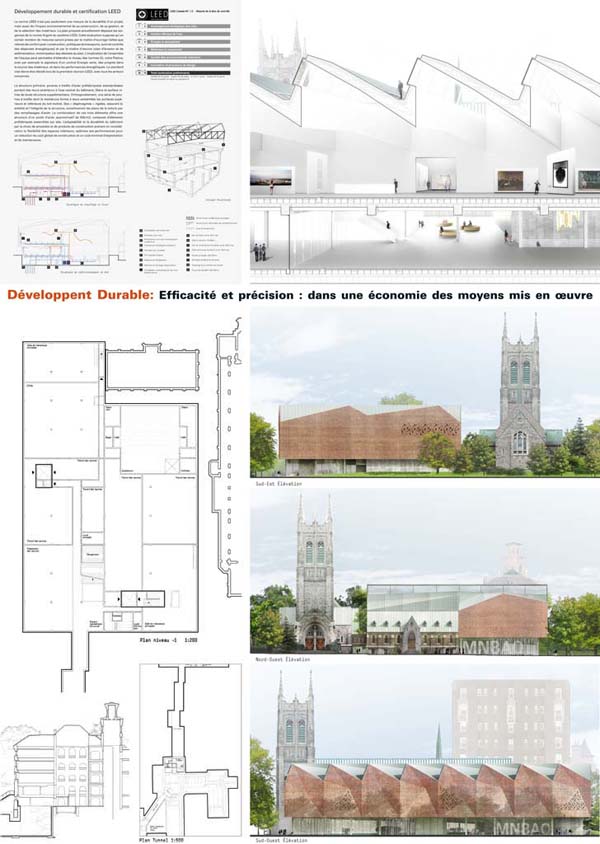

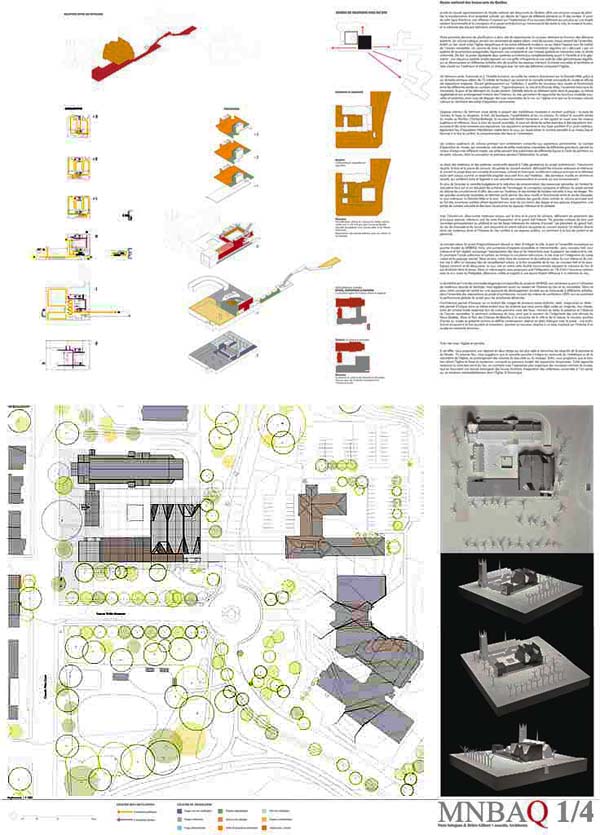

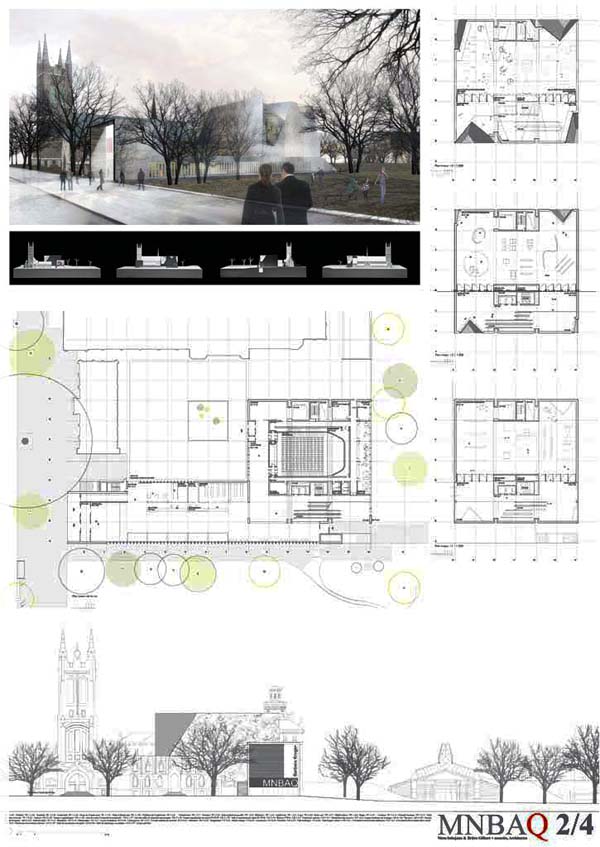

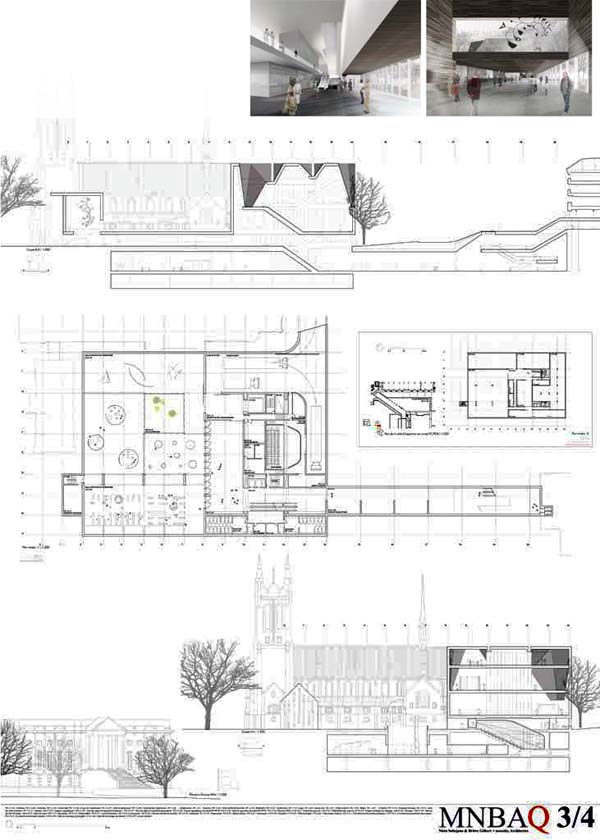

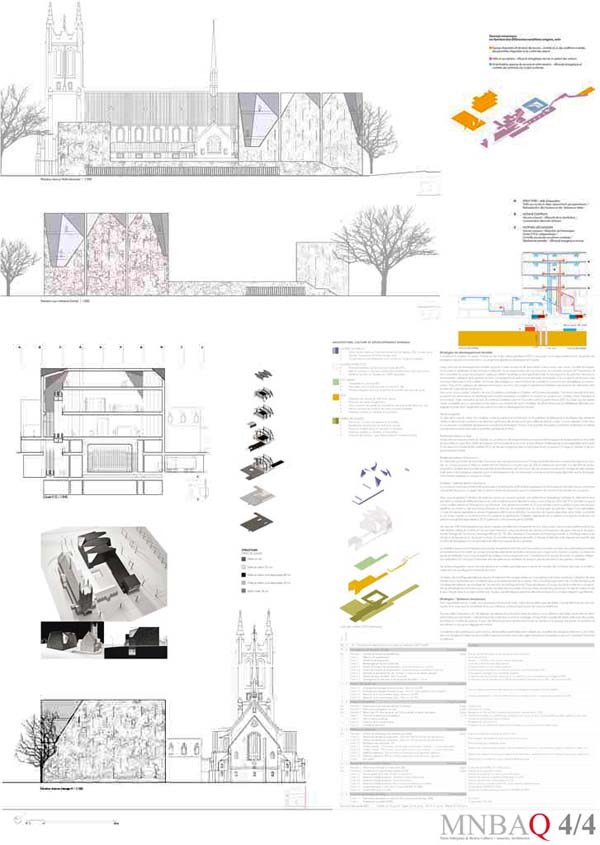

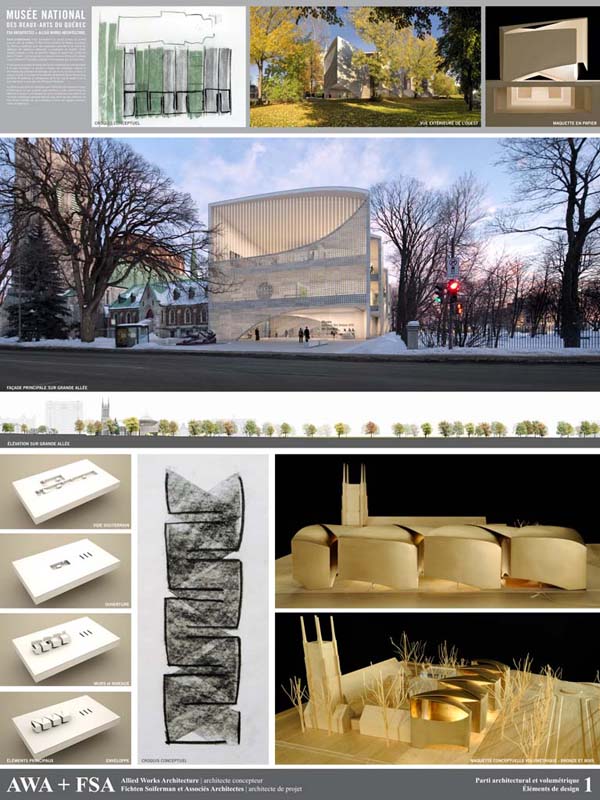

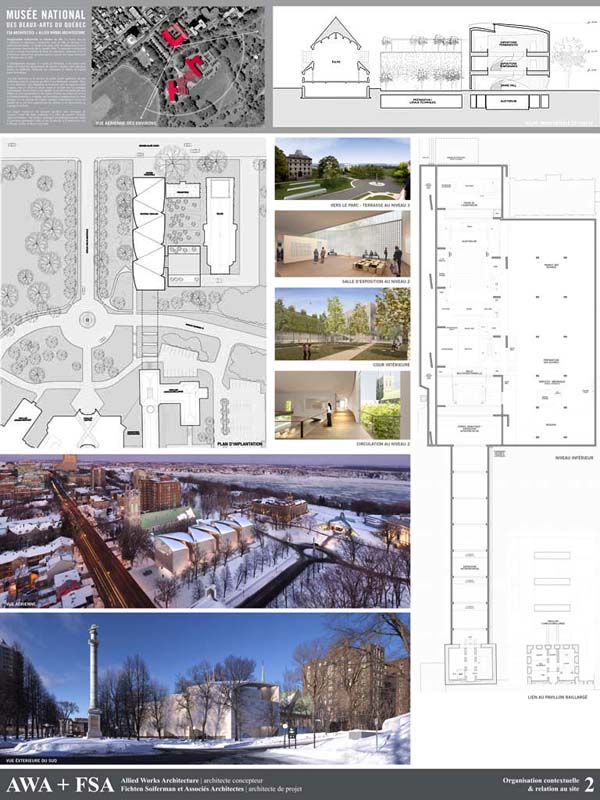

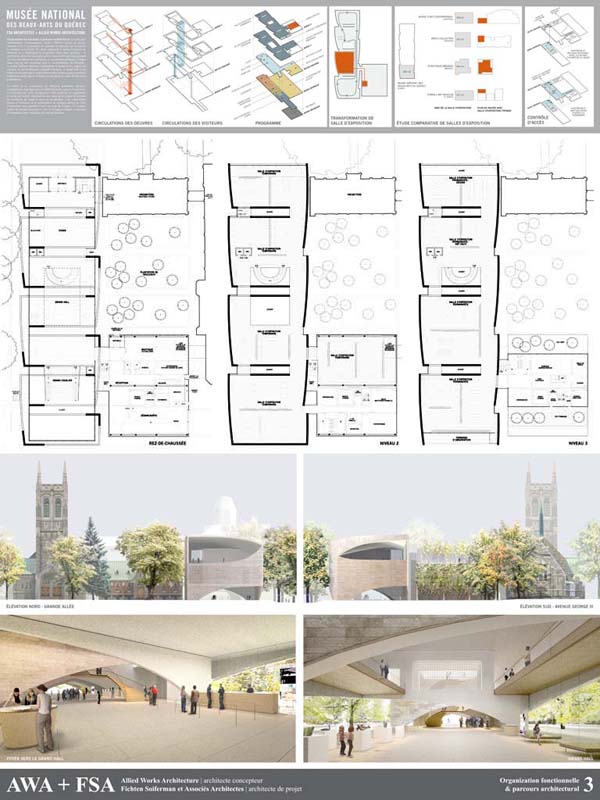

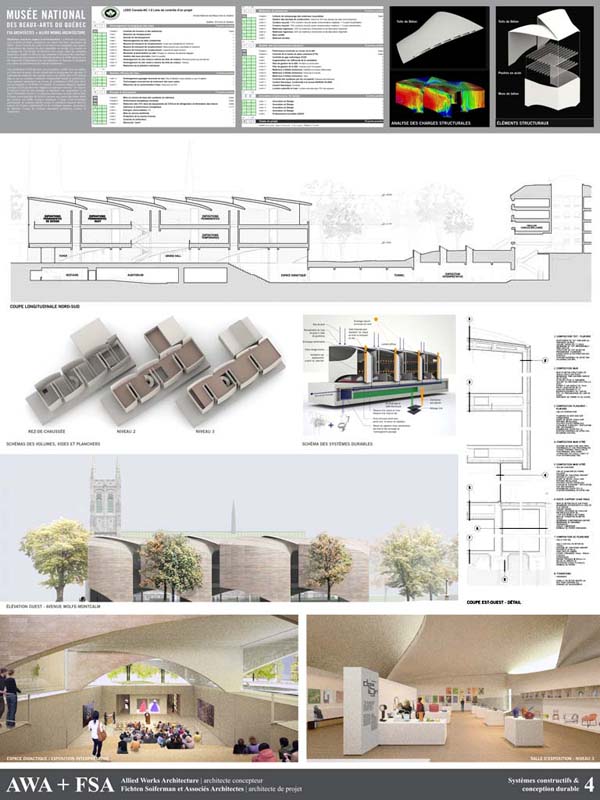

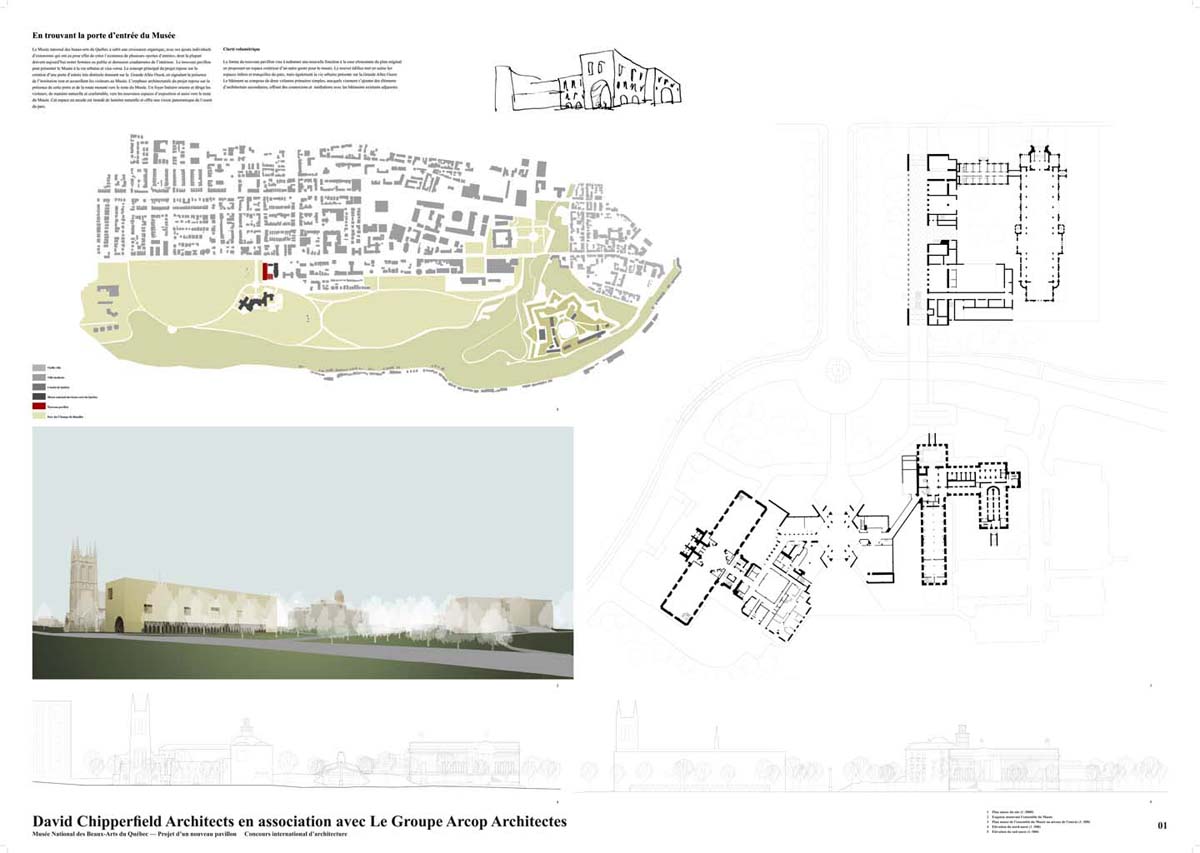

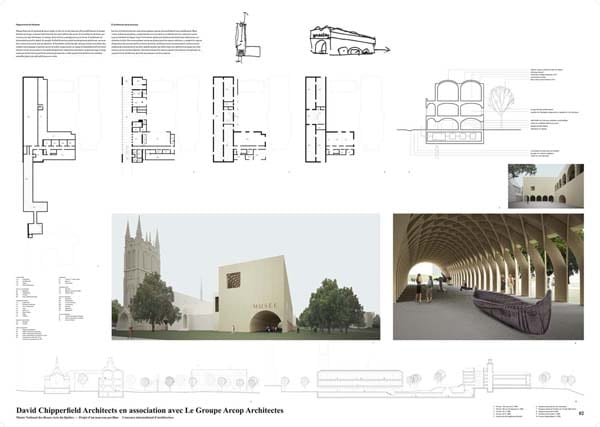

The competition called for a 10,000 sq-metre addition displaying art of the 20th and 21st centuries, connected by tunnels to a 1933 building and a renovated 1861 prison. An existing Dominican monastery was set to be demolished in order to make way for the new pavilion, while neighbouring Saint-Dominique church with its prominent steeple and presbytery were kept. The lot stretches from the city’s main street, the Grande-allée, down to the historic Plains of Abraham overlooking the St. Lawrence River. The addition would double the museum’s exhibition space, and bring the total surface area to 28, 876 sq metres.

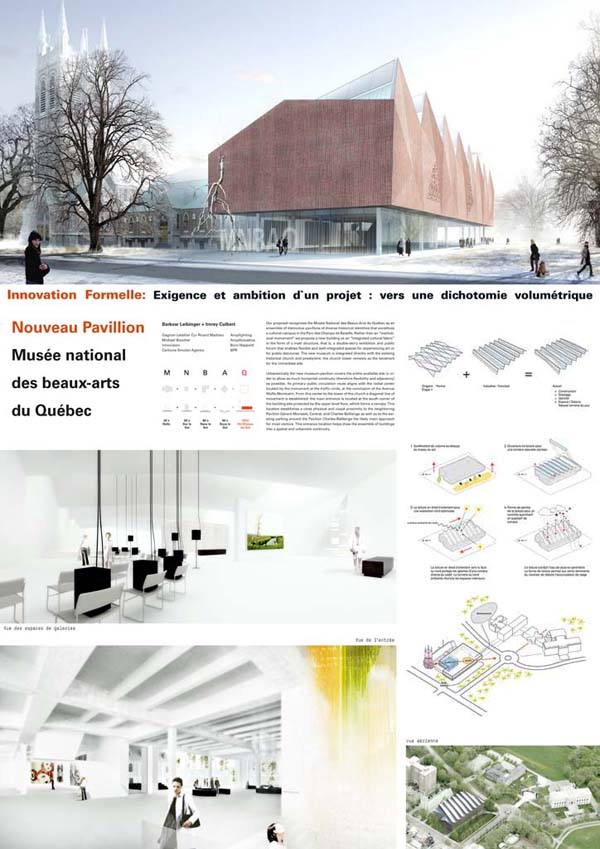

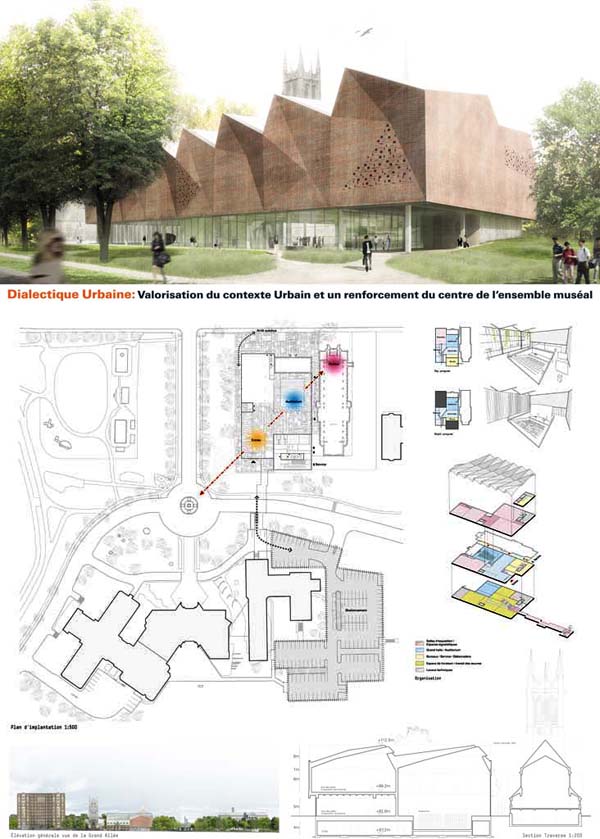

Besides OMA/Rem Koolhaas, there were four additional finalists competing in the second stage. They were: Nieto Sobeyano/Briére Gilbert et associés; Barkow Leibinger architekten/Imrey Culbert Architects; Allied Works Architecture/Fichten Soiferman et associés; and David Chipperfield/Arcop.

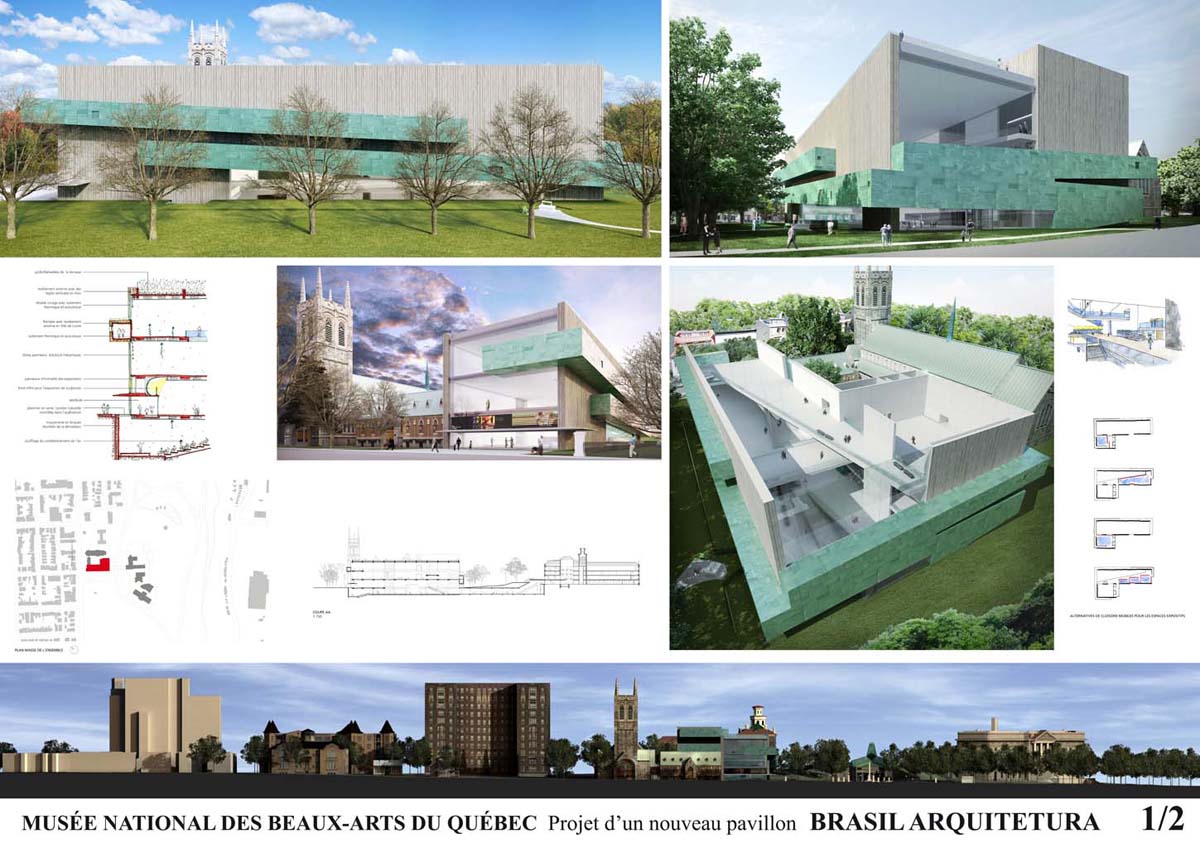

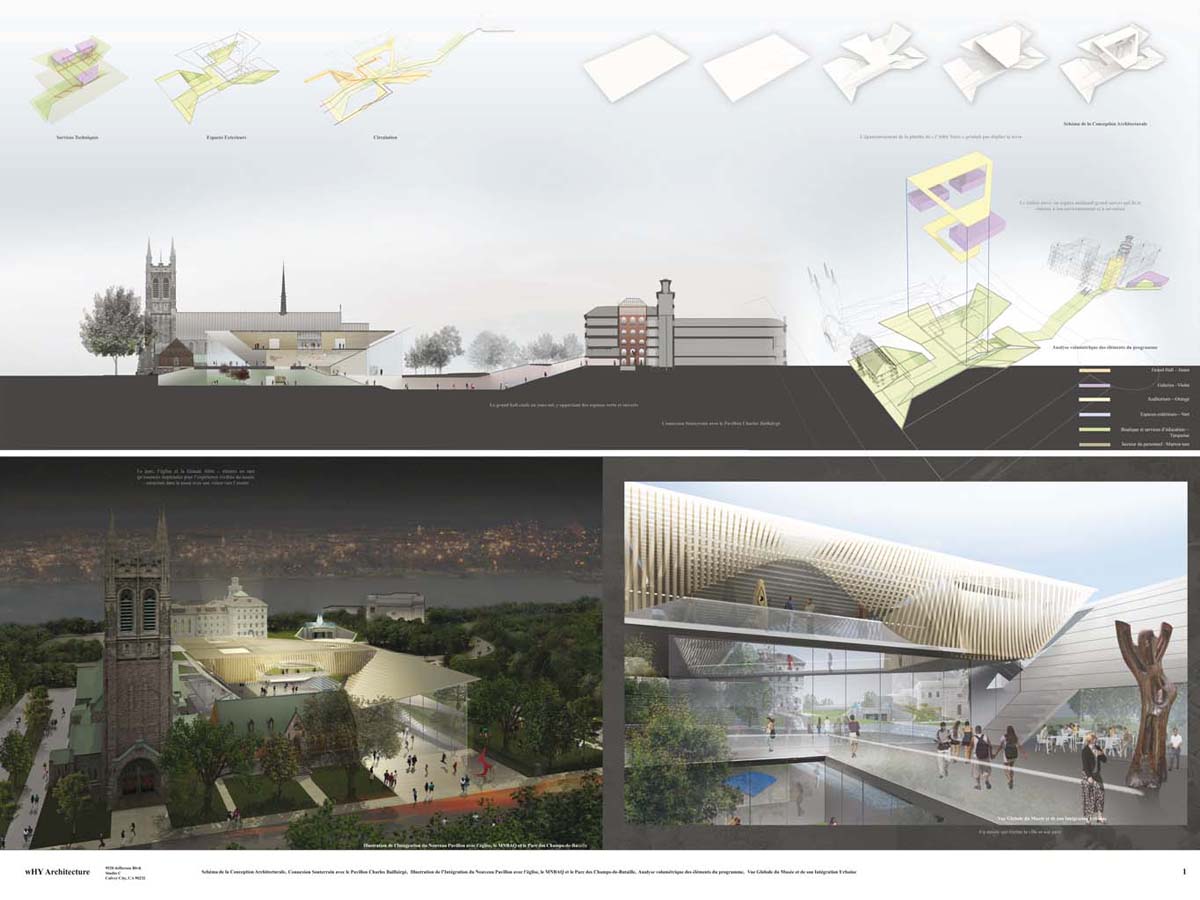

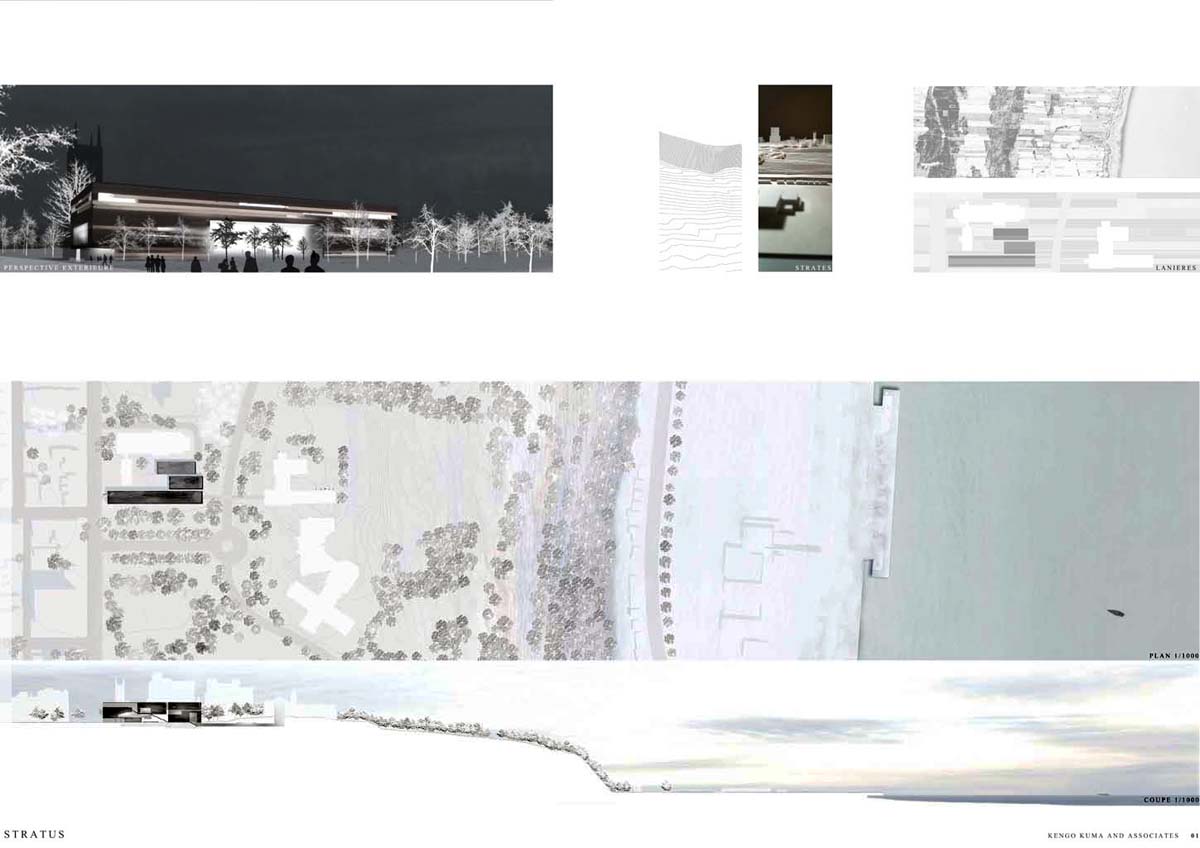

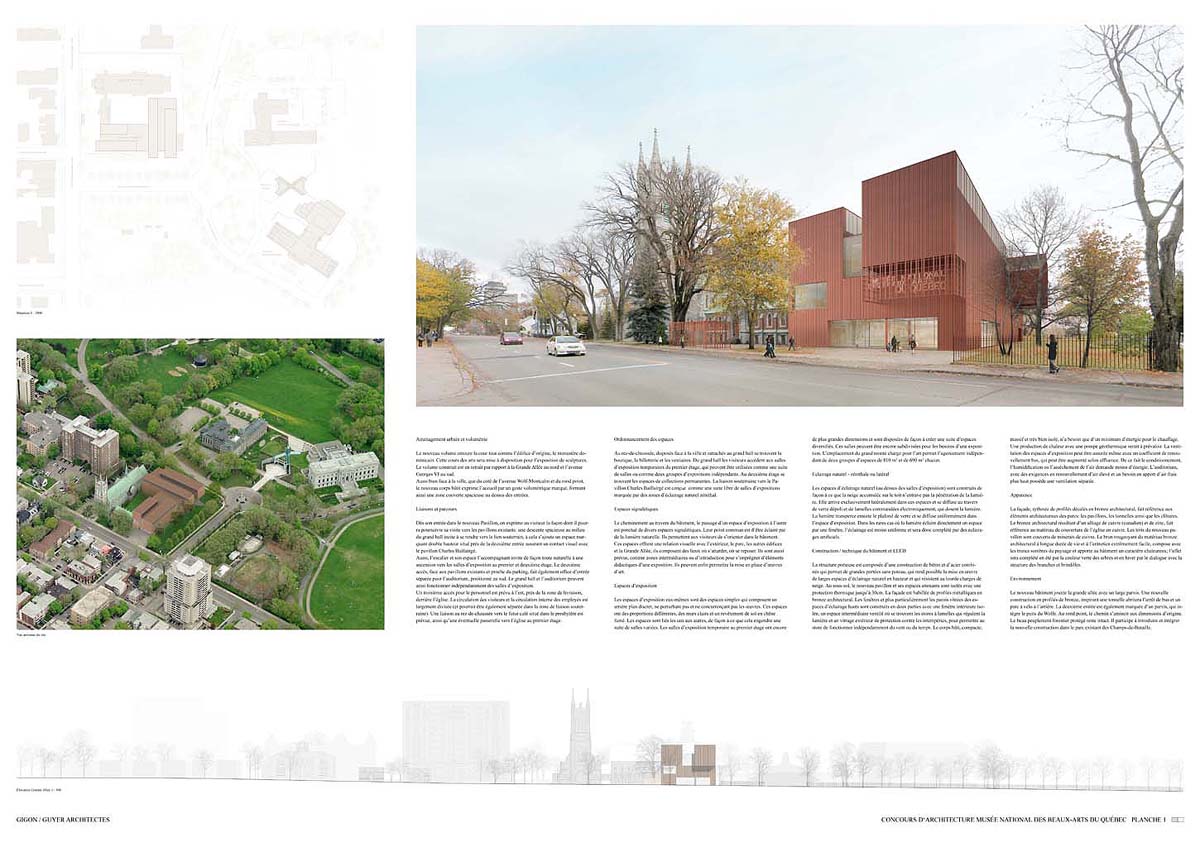

Notoble firms, who came under consideration, but were eliminated before the final round, were: Consortium Coté Leahy Cardas/Adjaye Associates, architectes; KUMA Associates; Gigon-Guyer, architects; GLCRM+KPMB, architectes; Saucier Perrotte/Bélanger Beauchimen Morency, architectes; Behnisch Architekten; BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group); M.C. Croft/J.Plante/Hudon Julien associés; wHY Architecture; and Brasil Arquitetura.

It was hardly a surprise to see OMA among the finalists. Guided by Rem Koolhaas’ canny disciplinary politics, OMA excels at promoting modern design within the contradictions of a globalized world. The MnbaQ project is surely another example of OMA at its globe-gobbling best. And yet many other entrants are also known for their ability to succeed in diverse political zones: David Chipperfield, Allied Works, David Adjaye, Behnisch, Snøhetta, GMP and BIG, just to name a few. The jury reports make it clear that OMA won not because of any political savvy—although jury members were on the watch for competitors’ willingness to listen and take direction; they were wary of divas—but because the proposal seemed to effortlessly fulfill very specific local demands. Shohei Shigematsu, the partner who runs OMA’s New York Office, led the project. His description of the proposal, enthusiastically quoted in the local press, shows an almost perfect understanding of the museum’s setting: “The building reflects the museum’s ambition and the city’s need to find a meeting point between the art the park and the city. . . . The concept is fairly simple: by lifting the ground we create a meeting space between the city and the park. The art becomes the link connecting the two.” OMA’s proposal carried the day because the team paid close attention to the particularities of the site.

Still, politics in Quebec are important. OMA’s winning in Quebec is no less remarkable as an outcome than when Renzo Piano and Richard Rodgers won the contest for the Pompidou Centre (Beaubourg) in Paris. It’s not that the MnbaQ reinvents downtown Quebec; or that a new architectural style is epitomized. In fact, OMA proposes a staid and simple landmark. But the name of the museum already indicates some of the issues. The city and the province bear the same name, but the museum is a provincial entity, not a municipal one. The museum’s mandate is to represent and promote a vision of the entire province. The Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec is a national museum; the nation in question is not Canada but the Province of Quebec. (A couple of hours up the St. Lawrence River, the equivalent museum in Montreal, the province’s largest city, bears only the city’s name.) As part of this mission, major capital investments are typically confided to Quebec professionals and entrepreneurs. How did it come to pass that international architects were allowed to build a national museum in the capital city of a province hyper-sensitive to the issue of independence, language, and internal development?

The first answer is branding. The driving force behind the project, museum director John Porter, and the benefactor and president of the museum’s foundation Pierre Lassonde, wanted the project to participate in the so-called Bilbao effect. They wanted the names of the architects themselves to bring media attention to their plans. And they wanted a building that would bookend Quebec City’s most famous building, the Chateau Frontenac, a railway hotel that sits at the other end of the Grande Allée. The seven-member jury, however, was much more focused on making sure the architects delivered a working museum. Two architects with international reputations, Nasrine Serjai and Xaveer De Geyter, joined André Bourassa representative of the Quebec Order of Architects, and Jacques White, a professor at the nearby School of Architecture at Université Laval. Two museum representatives—Porter and Esther Trépanier, and the jury chair, Charles-Mathieu Brunelle, the director of Montreal’s nature museums, rounded out the committee.

Another factor is that in open competitions, OMA competes against itself. While the winner has a prominent, daunting, theatrical cantilever defining the main entrance, others in the fifteen also used dramatic cantilevers and other ideas popularized by OMA. Indeed, Koolhaas’ prolific teaching and atelier-style office means many designers have direct experience of OMA strategies, forms, and preferences. The popularity of the office’s images, books, lectures, buildings, and the personality cult that surrounds Koolhaas mean that OMAish ideas permeate international design competitions, even when OMA doesn’t compete.

A third answer as to how an international firm won a commission to build, despite local politics, is that for twenty-five years, the province has been a rare district in North America that regularly holds competitions for public buildings. In brief, in Quebec any building project of a certain size using public funds must commission architects through an architectural competition. This policy has been successful and influential. Not all firms are happy with this policy, especially because there is no “second tier”; that is, while the policy can help young firms gain access to substantial projects, it also means that established firms have to compete in the wild, wild west. Although, not all commissions are given through competitions; there have been about fifteen per year throughout the province. Montreal, in particular, has a number of small, design-oriented firms whose business plan can be tied to the implementation of the competition format.

But alas! The MbanQ contest had the unfortunate effect of eliminating those small firms, mostly because they could not pass the first qualifying stage of the three-stage format. Of 76 firms who made an offer of services, the jury retained 15, five of which had to be Quebec-based. Those fifteen made a concept proposal, and the jury winnowed them to five. Those five had two more months to prepare further plans based on the jury’s comments, and to present their proposals in person. At that point, the team had to contain an experienced architect licensed to work in Quebec. OMA, for example, teamed up with Montreal-based Provencher Roy architects.

One thing that at first didn’t play a role as much as it can in Canada is budgets. Morphosis partner and Pritzker Prize-winner Thom Mayne once complained, after working on a graduate student residence for the University of Toronto in Ontario, that the budget was less than a parking garage in the U.S. The budget for the MbanQ building is set at CAN$90 million, with funding coming also equally from private donations and two layers of government.

The budget problem may be one of the lasting legacies of the competition. In the last quarter century, the mobility of architects between jurisdictions in Canada as well as commissions by firms based outside of Canada, have been dogged by low budgets. The initial vision that enabled high-profile designers to win has been seriously compromised by a confrontation with the financial realities. At this writing, the OMA/Provencher Roy et associés partnership have already seen their first call for tenders recalled: the first offers all surpassed their estimates. It remains to be seen if the solution will be more fundraising and an increased budget, changes in details and finishes, or, even changes in the design.

It’s a strange quandary to have budget problems, because the level of support for getting the architecture “right” has been quite high throughout the competition process. For example, the jury reports have been made public, and the MNABQ has adopted the internet (www.plusdespacepourlart.ca) and social media for an unprecedented public involvement. The museum also entered an unusual partnership with L.e.a.p., a research project cataloguing architectural competitions based at the Université de Montréal (www.leap.umontreal.ca and www.ccc.umontreal.ca), presenting all of the projects in the competition immediately upon the announcement of the winner. This method of accessible, public diffusion, not just of the winner but, so to speak, of the workings of an architectural competition itself, is a model for transparency in competitions everywhere.

David Theodore, a frequent contributor to COMPETITIONS and CANADIAN ARCHITECT, is a writer based in Montreal.

Winning Entry: OMA/Provencher Roy et Associés, architectes

Note: All photos courtesy of Catalogue des Concours Canadiens, L.E.A.P., Université de Montréal