by Dan Madryga

Taichung is a city with grand ambitions. Taiwan’s third largest metropolis has been developing an impressive inventory of architecture and planning projects that envision the city as a new hub for design innovation and inspiration. And as in Taipei and Kaohsiung, open international design competitions are an important part of this process, attracting creative talent from around the globe and prompting compelling, forward-thinking designs. Taichung first garnered the attention of the global design community with 2010’s Taiwan Tower Competition, a forum that sought an iconic design for a landmark observation tower commemorating the centennial anniversary of the founding of Taiwan. The winning project, an eye-catching, garden-topped “21st Century Oasis” designed by Japanese architect Sou Fujimoto, is sure to become a major attraction for the city.

Now, the Taichung City Government has wrapped up a landscape and planning competition that once again attracted worldwide participation and produced intriguing results. The winner of the Taichung Gateway Park Competition, designed by Catherine Mosbach, Philippe Rahm, and Ricky Liu and Associates, has the potential to break new ground in sustainable landscape design.

Gateway Park will be a key component of Taichung Gateway City, an ambitious urban planning scheme intended to rebrand the city as a visionary, sustainable metropolis. The project first materialized soon after the 2004 closing of Taichung’s outdated Shuinan Airport, which provided a virtually clean slate upon which to devise a large new urban district (the airport’s old Hangar A15 has been converted into an exhibition center that publicly showcases Gateway City’s various ongoing projects). With a goal of creating a diverse, integrated community, Gateway City will meld together commercial, residential, cultural, and recreational functions, with an emphasis on innovative design strategies and an eco-friendly modus operandi.

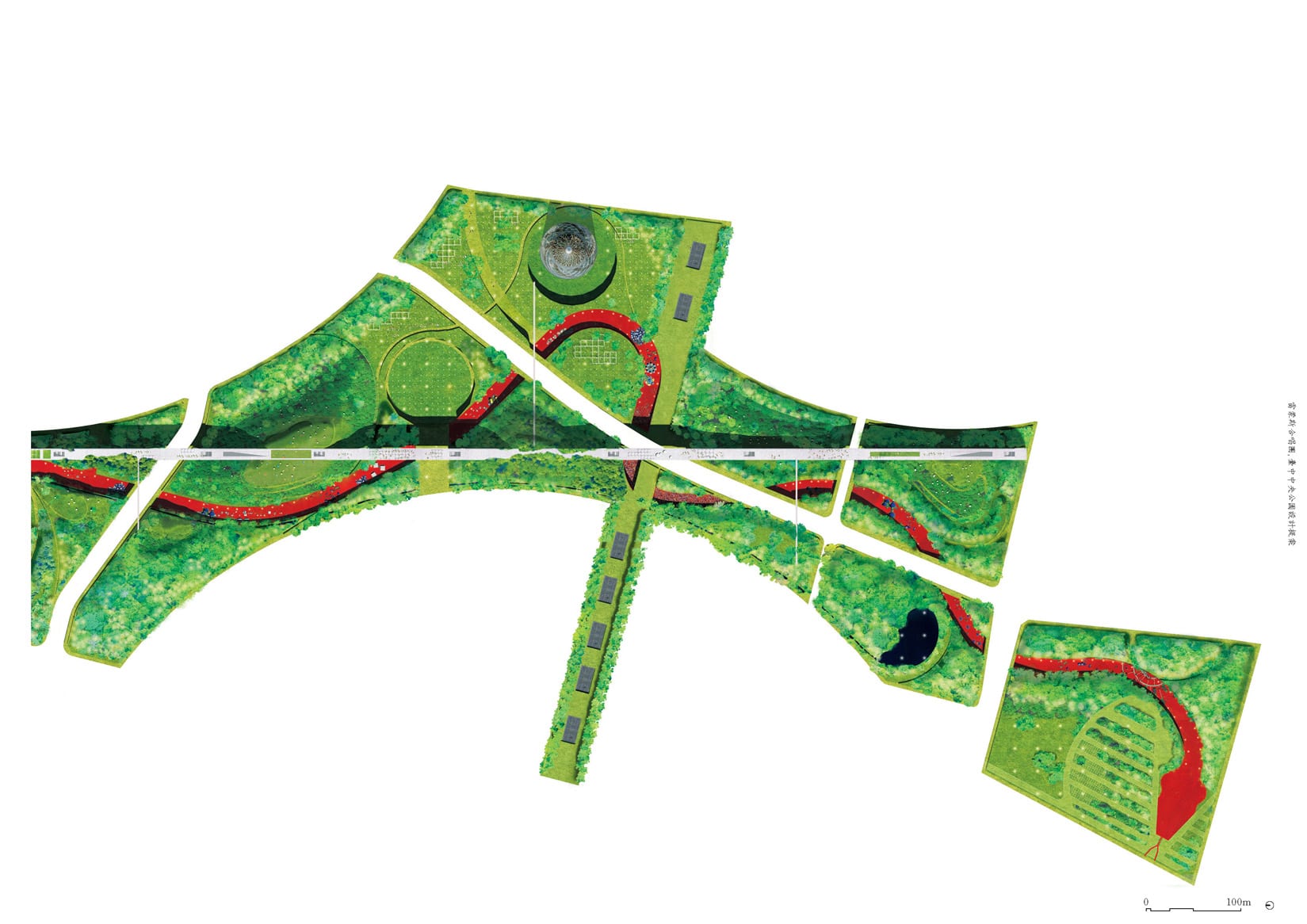

Serving as the central backbone of the new community, Gateway Park will help set the standard for Gateway City’s subsequent development. The open, two-stage competition challenged architects, planners, and landscape architects to develop a meandering 168-acre parcel of land into a functionally complex recreational park running north to south through the new city, linking its various functional zones. The competition organizers sought a park that combined “tranquility, ecology, landscaping, disaster mitigation, carbon reduction and recreation.” Various recreational and cultural facilities had to be skillfully integrated into the park’s fabric, including a Cultural Center, Movie City, and the aforementioned Taiwan Tower. With a preliminary construction budget set at approximately US$85,000,000, the park is certainly a large-scale, high stakes endeavor with great potential.

Above all else, emphasis has been placed on Gateway Park’s intended role as an eco-park, and designs were to be judged with an eye for inventive, boundary-pushing concepts that might brand the park as a progressive, international role model of sustainable design.

After preliminary Stage One submissions, the pool of talent was pared down to four shortlisted teams, who were given three months to develop their designs. A jury panel that balanced local Taiwanese design talent with notable foreign figures gathered to review the final submissions:

- Chi-yi Chang (Taiwan), Director of Graduate Institute of Architecture, NCTU

- Li-shin Chang (Taiwan), Associate Professor of Landscape and Urban Design, Chaoyang University of Technology

- Mario Cucinella (Italy), Mario Cucinella Architects

- John K.C. Liu (Taiwan), Professor, Graduate Institute of Building and Planning, National Taiwan University

- Charles Waldheim (USA), Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture at Harvard

- Minghung Wang (Taiwan), professor, NCKU, ROC

- Riken Yamamoto (Japan), professor.

First Prize: “Atmospheres of Well-Being”

by Catherine Mosbach, Philippe Rahm, Ricky Lui & Associates

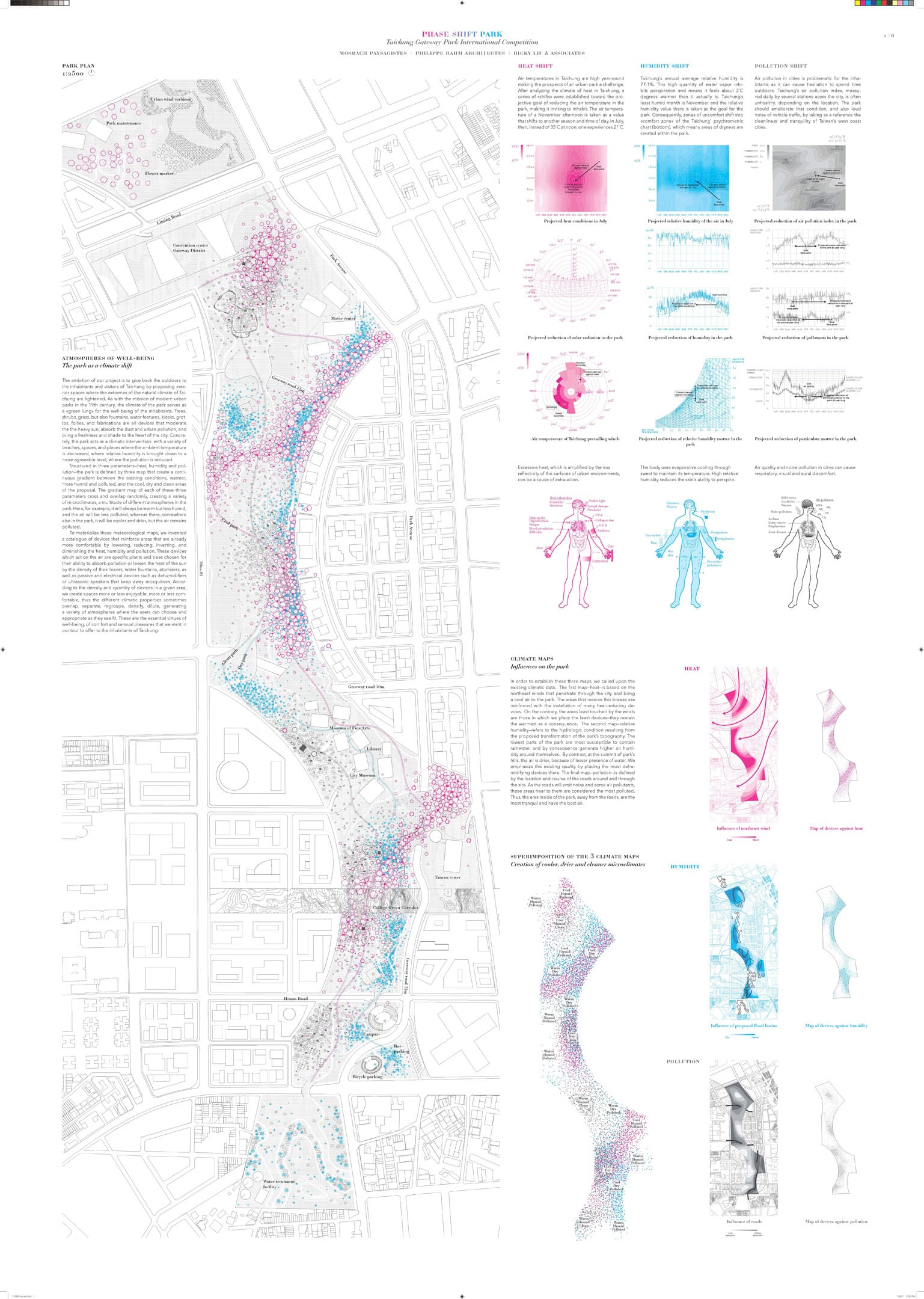

While each shortlisted project contained intriguing ideas, one entry stood out above all others, greatly impressing the jury. The winning project, “Atmospheres of Well-Being: The Park as a Climate Shift,” proposes a radical new concept in landscape design: a park that creates and controls a range of microclimates and atmospheres by means of natural and artificial devices. Employing a rigorous analytical process, the winning design is an innovative proposal that reconsiders the potential of landscape design and its role in the ever-evolving sustainability movement.

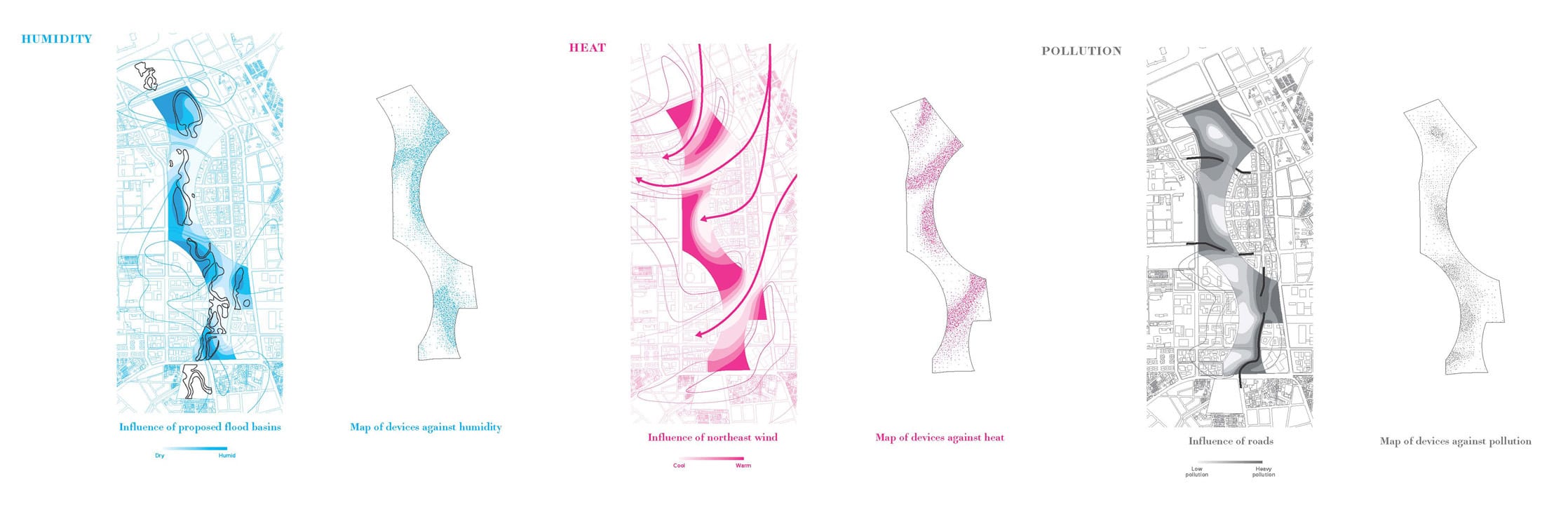

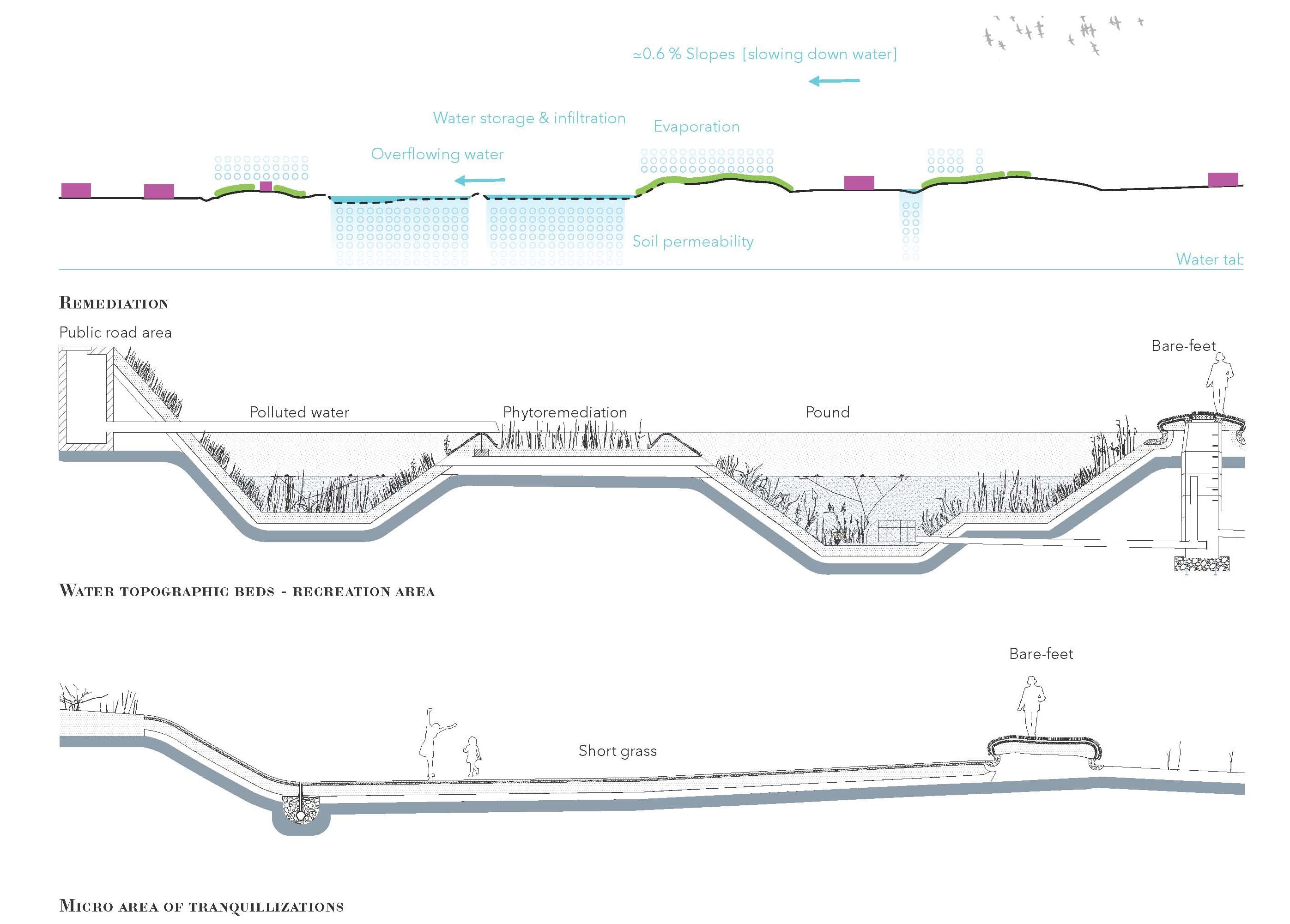

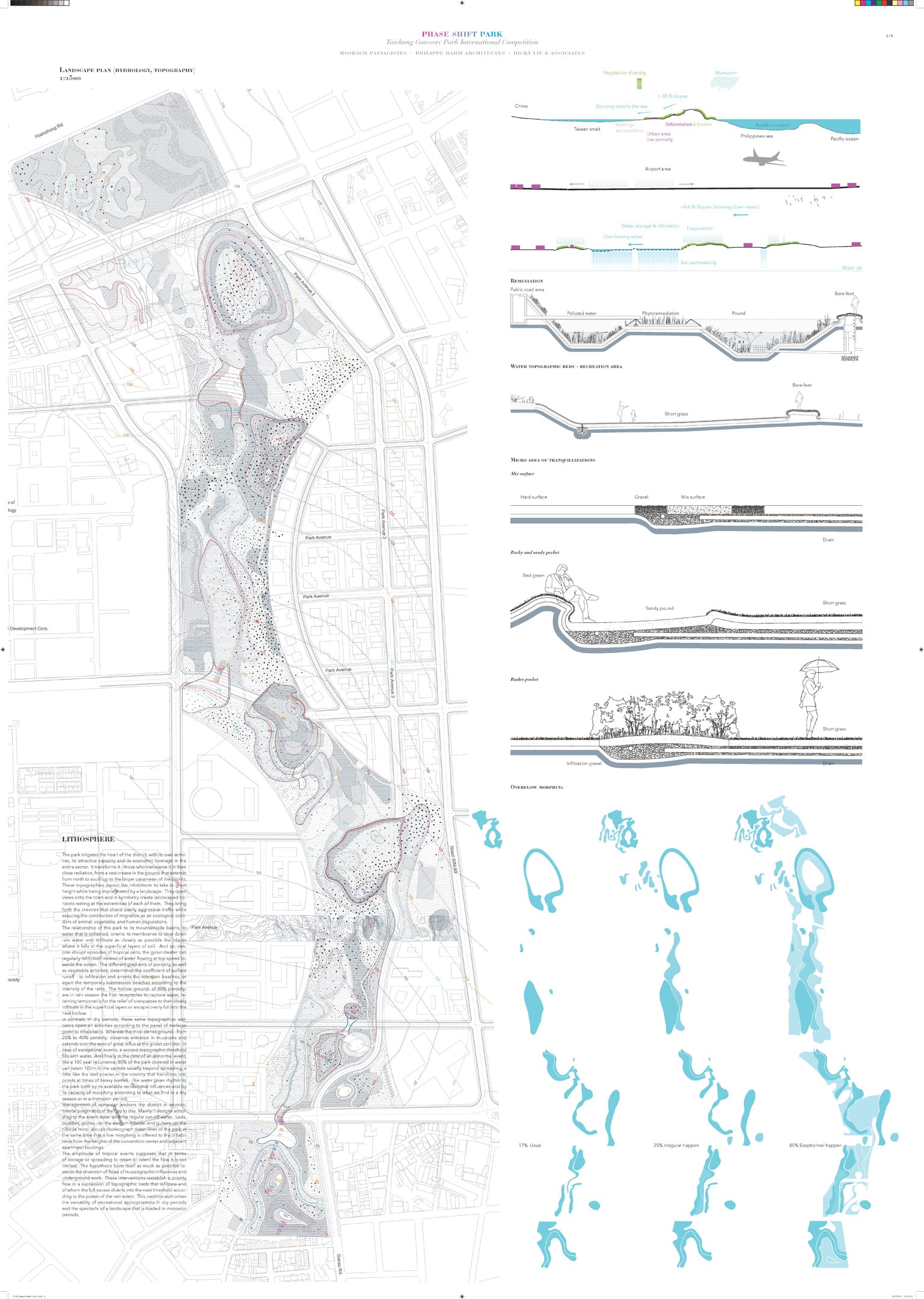

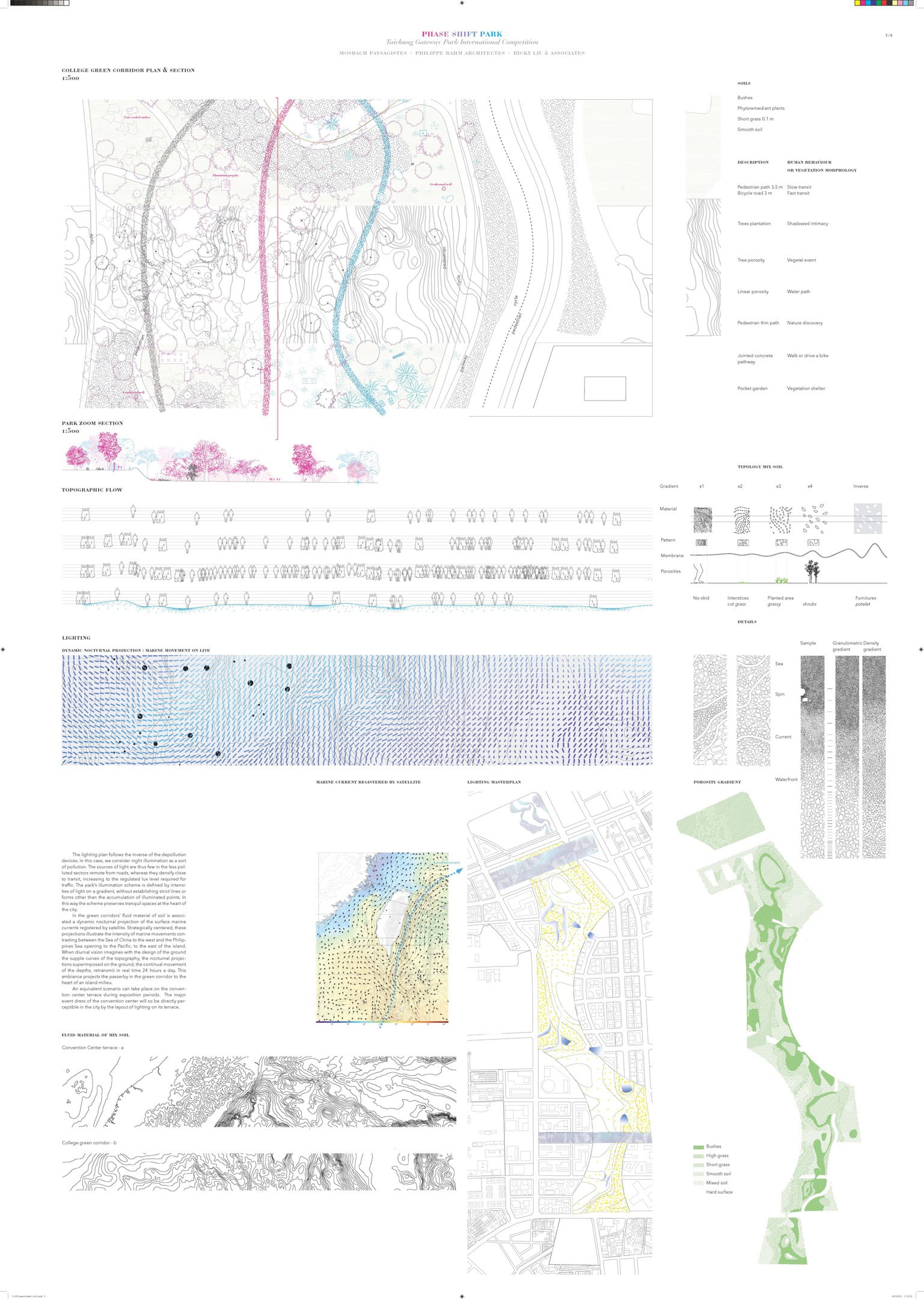

The park is structured by three parameters – heat, humidity, and pollution – that variously overlap and create a multitude of microclimates and atmospheres. The team carefully studied and mapped the existing environmental conditions of the site to determine the most ideal locations for the various park functions. For instance, leisurely outdoor activities such as cafes and open-air restaurants are placed in cool-air microclimates, while the largely indoor functions of the Cultural Center, Taiwan Tower and Taichung Movie City are placed in warmer areas. As physical exertion is most ideal in climates of low humidity, sports and recreation fields are placed in dry-air zones, and playgrounds are located in areas with the cleanest air.

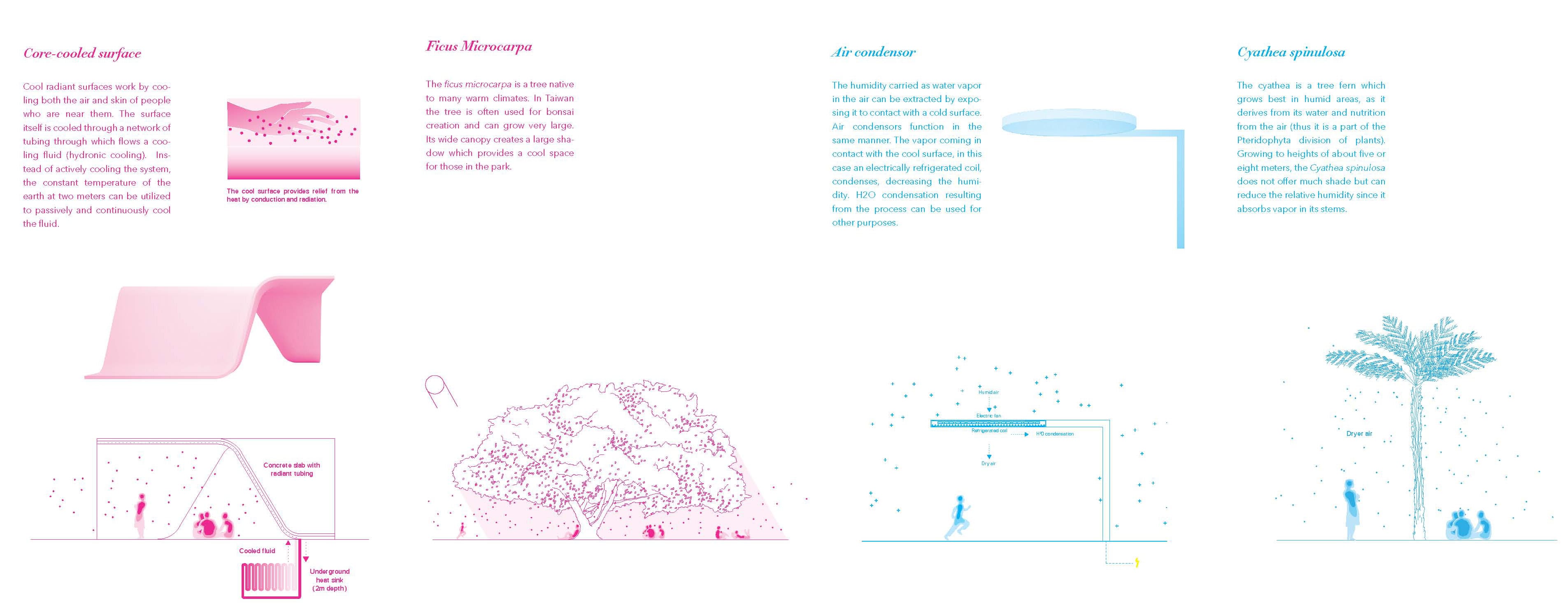

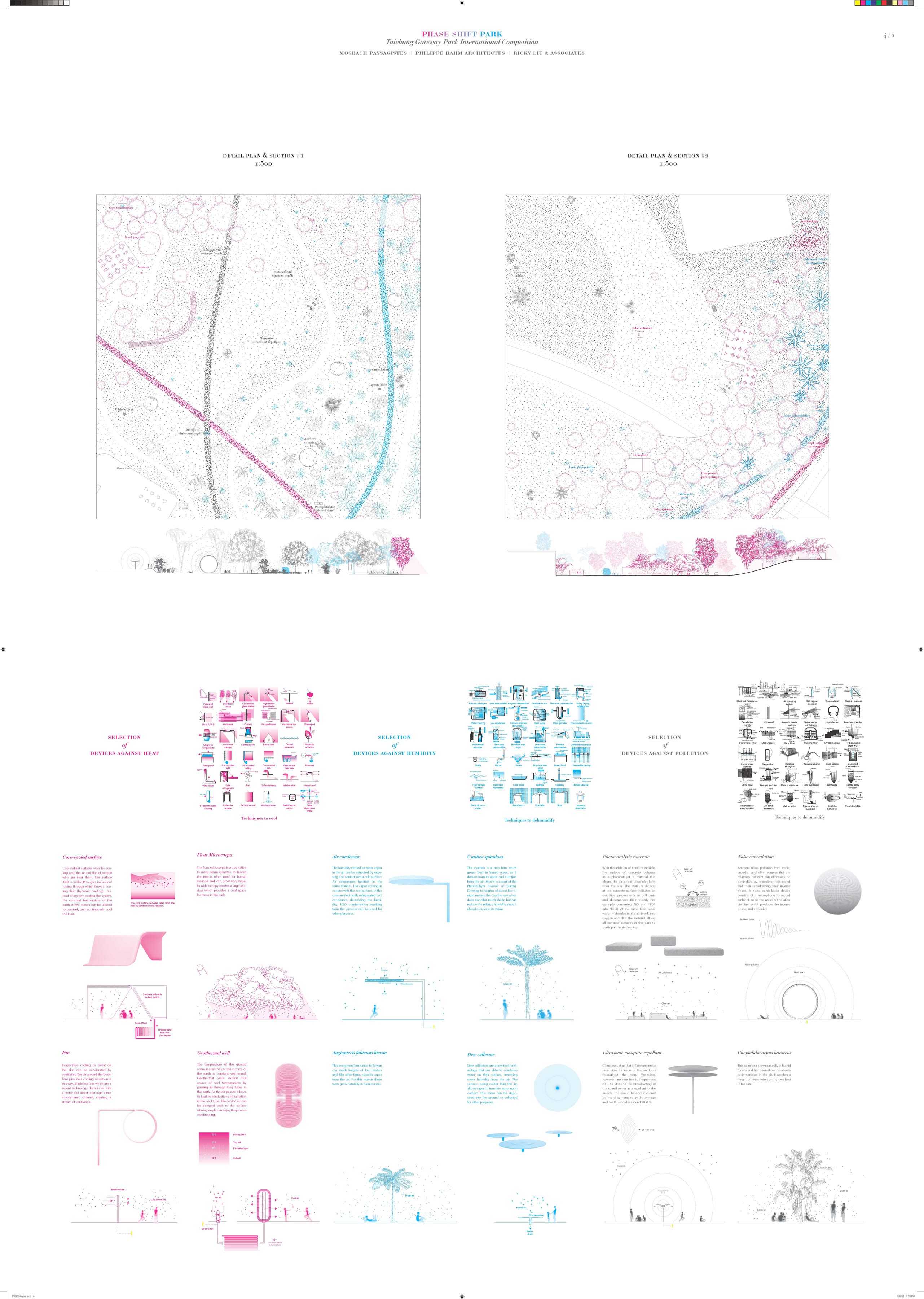

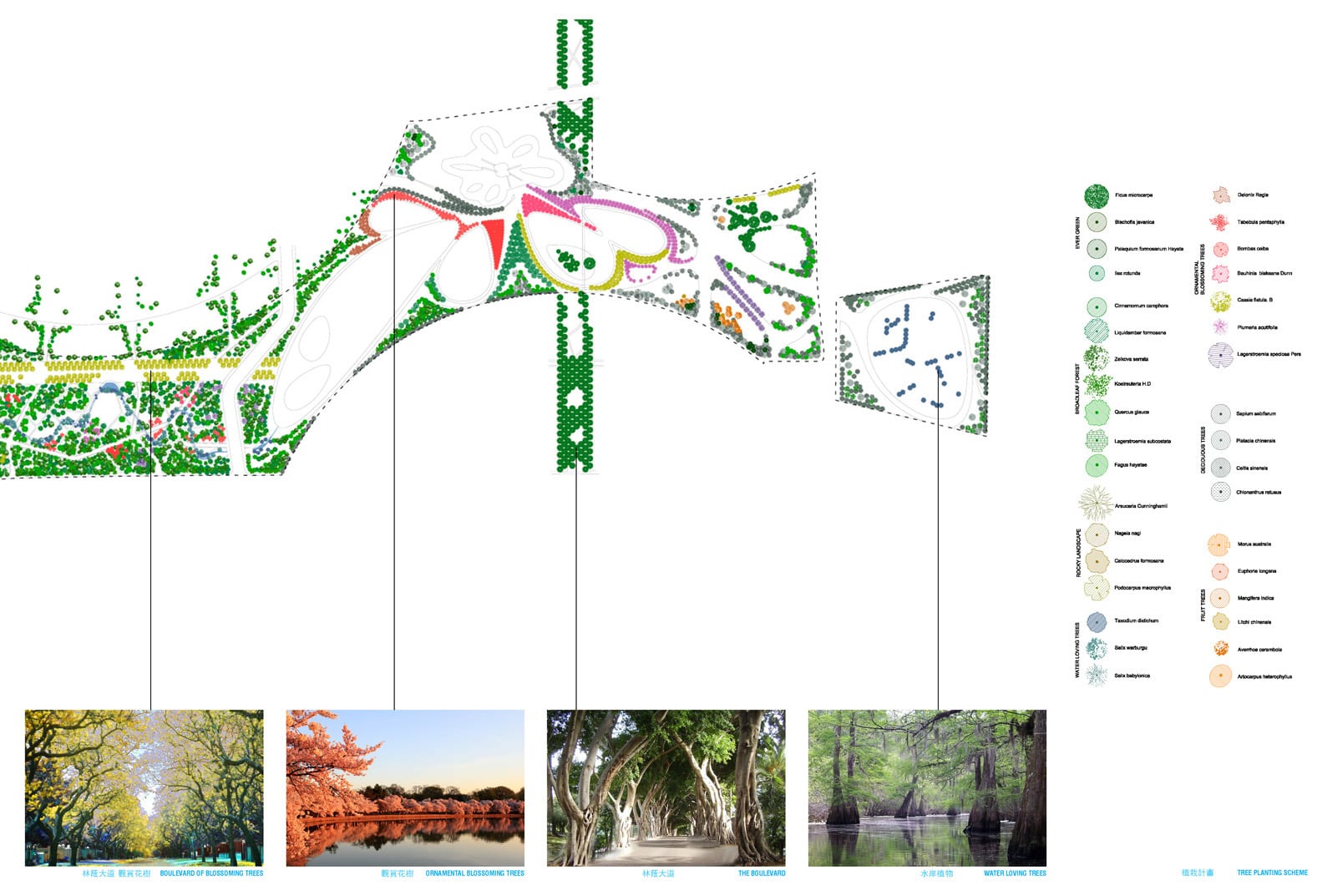

To further maintain and enhance the desired microclimates of the park, the team has created a well-researched catalogue of climate-controlling devices ranging from natural plantings, to passive design strategies, to state-of-the-art technologies. A palate of indigenous trees and plants have been selected for their various virtues of positive climatic impact, from the wide-canopied, shade-providing Ficus microcarpa tree to the Cyathea spinulosa, a tree fern whose stems absorb vapor in areas of high humidity.

The list of designed devices is quite extensive. Concrete “grottoes,” their surfaces cooled through a network of fluid-filled radiant tubing, will provide refreshing shelters of repose. Geothermal wells will utilize cool subterranean temperatures to generate passive air conditioning. Specially designed air condenser and dew collectors will control humidity in particularly muggy areas. To fight air pollution, street furniture will be made of photocatalytic concrete, a titanium dioxide-infused material that cleans the air under ultraviolet from the sun. Even noise pollution is dealt with: large spherical devices record the sound of noise pollution and broadcast back their inverse phase, effectively diminishing unwanted ambient sounds. The list goes on. In fact, the team’s presentation is chock-full of detailed maps, charts, diagrams, and illustrations that attest to the vast amount of research and analysis that went into the project.

This intensively eco-driven approach wowed the majority of jury members. “Taichung’s future starts here,” proclaimed one jury member, impressed with the scheme’s analytic approach to harnessing and controlling natural energy. Others praised it as a potentially new design paradigm in the making, an opportunity for Taichung to be at the forefront of innovative, sustainable landscape architecture and planning: “[the plan is] one giant leap for Taichung’s goal to improve its environmental quality; one powerful push for creativity in the global architectural and landscape design realm.”

The unorthodox approach is unsurprising when considering the team members’ design history. Leading the winning team, Paris-based landscape architect Catherine Mosbach approaches her chosen field with an innovative, phenomenological slant, which considers sensory experiences that go beyond the standard visual-centric norms. Her best-known project to date, the Bordeaux Botanical Garden, is an innovative research facility that deftly and evocatively balances science and art.

In a similar experimental vein, the architecture of collaborator Philippe Rahm is unique in its focus on generating a range of specific, function-derived climatic atmospheres. Spatial form, composition and materiality are dictated by the specific qualities of temperature, light, and humidity desired to provide inhabitants an appropriate degree of comfort necessary in a given space.

While the team members have developed and refined their individual ideas on a range of small projects, the Taichung Gateway Park gives them an ideal opportunity to test the concept of creating and controlling microclimates on a much larger scale. (The influence of the more conventional joint tenderer Ricky Liu & Associates is not as readily apparent, but it should be noted that the firm has enjoyed previous success in Taiwanese design competitions, having won commission for the 2010 Taiwan Center for Disease Control Competition.)

Park sections (click to enlarge)

This experimental approach naturally carries with it an element of risk, and the winning entry was not without its criticism. One jury member in particular expressed skepticism in such an untested conceptual framework, questioning the reliability of the microclimate data and citing the team’s lack of experience on large-scale projects.

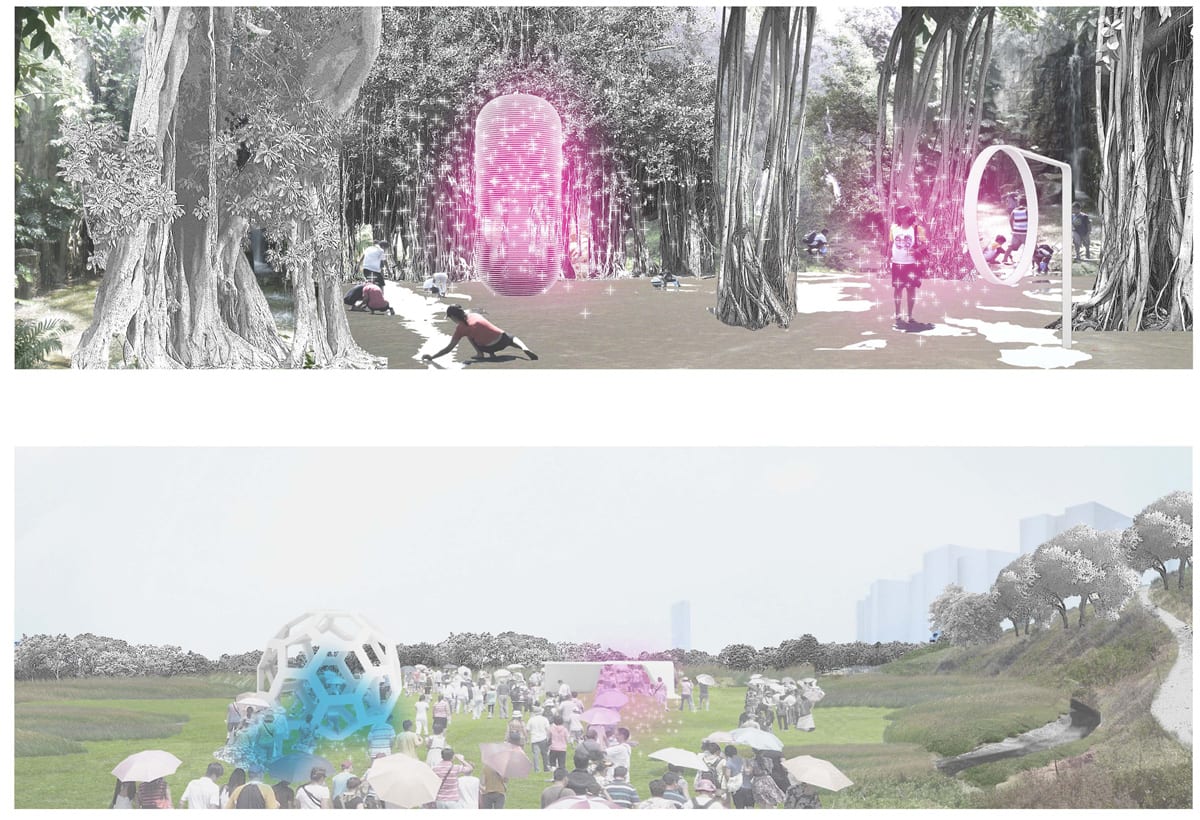

Some jury members were also concerned that with so much attention afforded to the technical aspects of the park, the team’s design presentation offers very little in the way of concrete imagery or aesthetic sensibility. The imagery in particular bears the unmistakable fingerprints of Rahm, who favors abstract spatial diagrams documenting the climatic qualities of temperature, light and humidity over the usual flashy architectural photos and renderings. The few renderings provided in the heavily diagrammatic presentation are rather impressionistic collages that fall short of conjuring an artful interpretation of the team’s innovative conceptual framework. Compared to presentation boards of the other finalists, there is little sense as to what their park will actually look like.

Yet in some ways this is a welcome inversion of the recent trend in design competitions, where flashy façades are generated with little or no consideration of underlying technical issues. Here, in an updated version of the familiar old modernist credo, form follows climate. It is a testament to the jury’s faith in the winning team to trust that the aesthetics of the park will be refined as the project continues to develop. Mosbach in particular has proved more than capable of creating beautiful, compelling landscapes in her past projects, and it will be interesting to see how her singular aesthetic sensibilities inform the evolving design. There is certainly risk involved in this experimental scheme, but there is also great opportunity for an influential, groundbreaking landscape environment.

In the persistently sluggish global economy, it often seems as though inspired, innovative design ideas are relegated the presentation boards of ideas competitions, to be briefly discussed but never to be built. Taichung’s recent series of open competitions for Gateway City are thus a welcome breath of fresh air in what has lately been a rather stagnant competition culture. The recent streak of Taiwanese competitions is allowing intelligent young design firms the opportunity to tackle large-scale projects with their potentially game-changing visions. And with any luck, Taichung Gateway Park will soon be an important destination for those interested in cutting-edge landscape design.

Third Prize

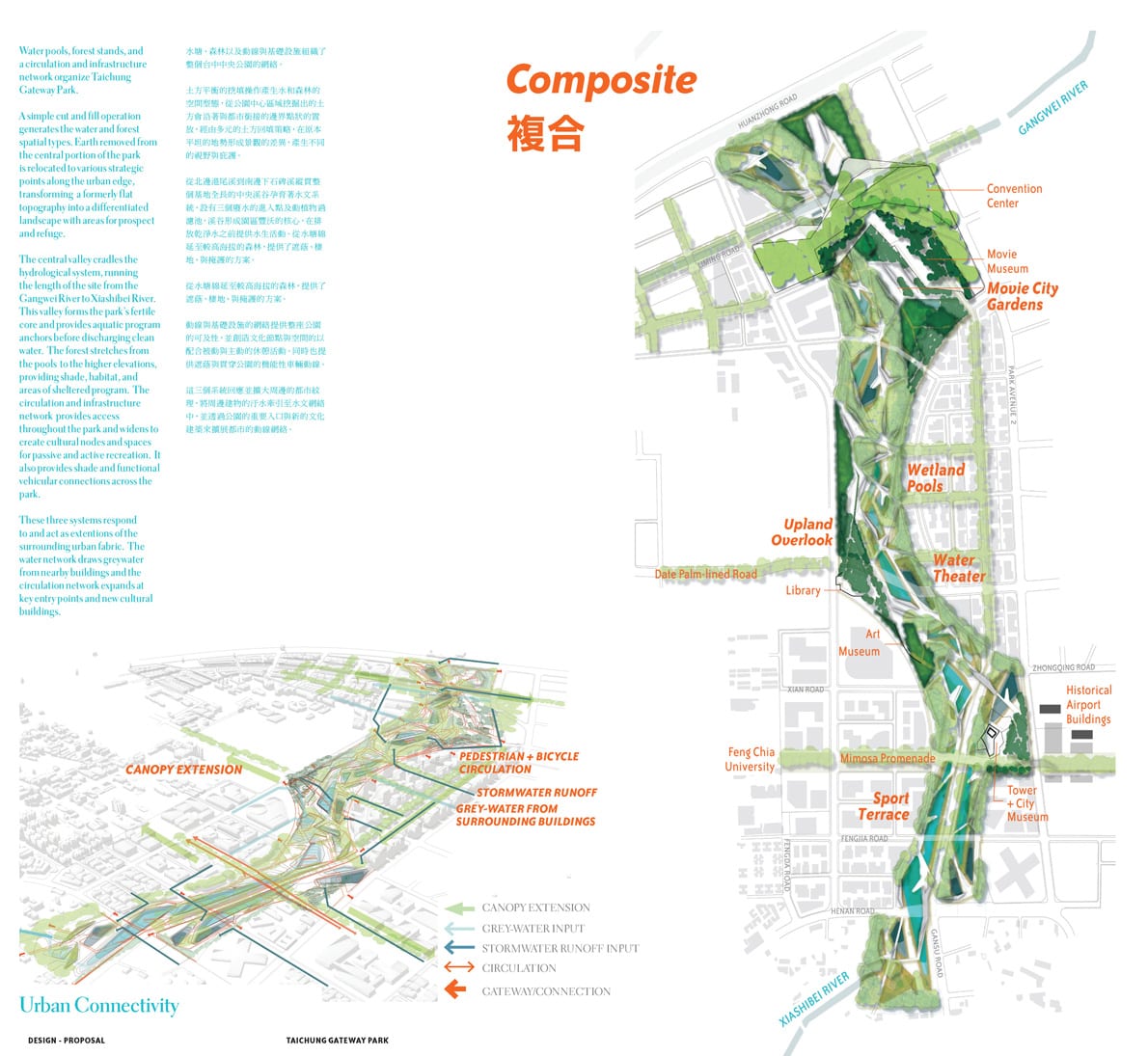

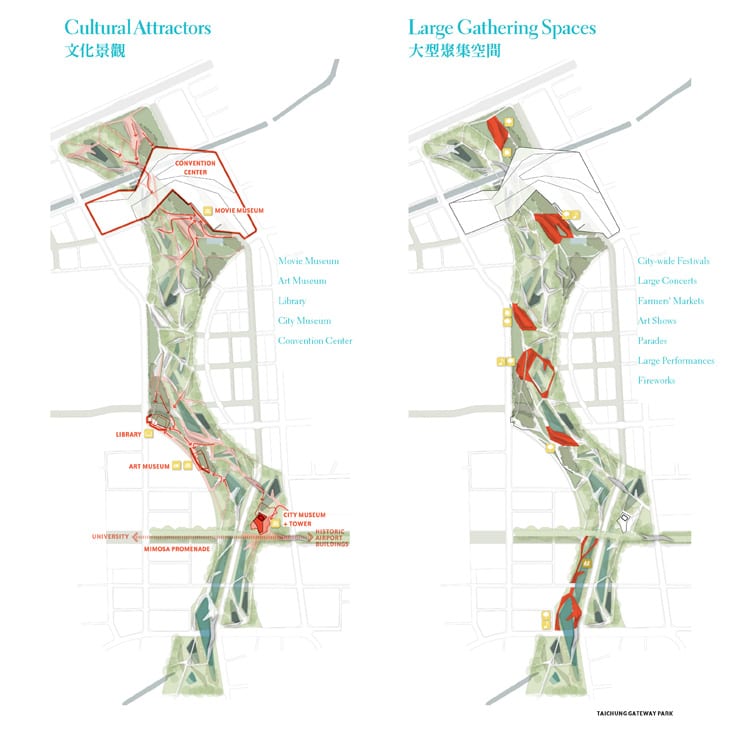

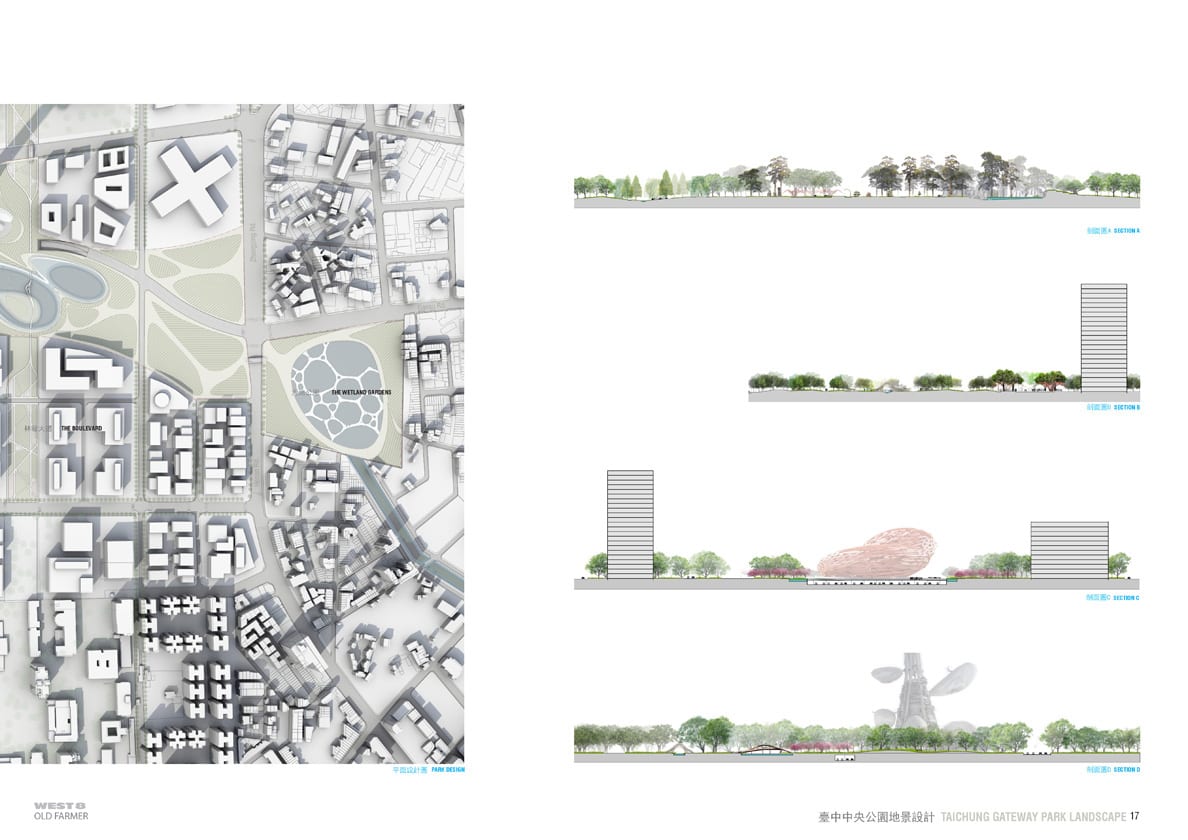

by West 8 Urban Design and Landscape Architecture (Netherlands), Old Farmer Landscape Architecture Co. (R.O.C.)

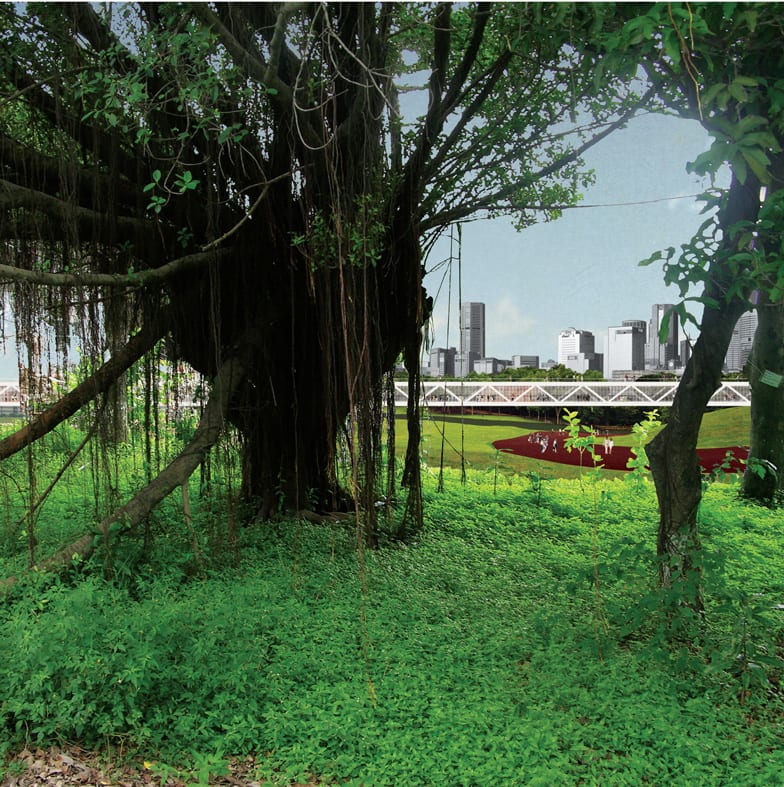

This entry created an “artistic representation of the diversity and beauty of the Taiwanese landscape.” Divided into six “atmospheres:” the Orchard, the Babylon Stones, the Cascading Waters, the Bouquet of Culture, the Sport Facilities, and the Wetland Gardens, the jury liked the scheme’s diversity and vivid, memorable imagery. A concern was voiced that “the recreated landscapes had an artificial quality, and that a closed circuit water system was high in energy consumption and not fitting to the eco-park idea.” Moreover, they noted a weakness in pedestrian circulation: Not much thought was given to the interrelation between the areas of the park.

Honorable Mention:

by Martino Tattara (Belgium), Pier Vittorio Aureli, Branzi Architetto, Favero & Milan Engineering, Tai Architects and Associates (R.O.C.)

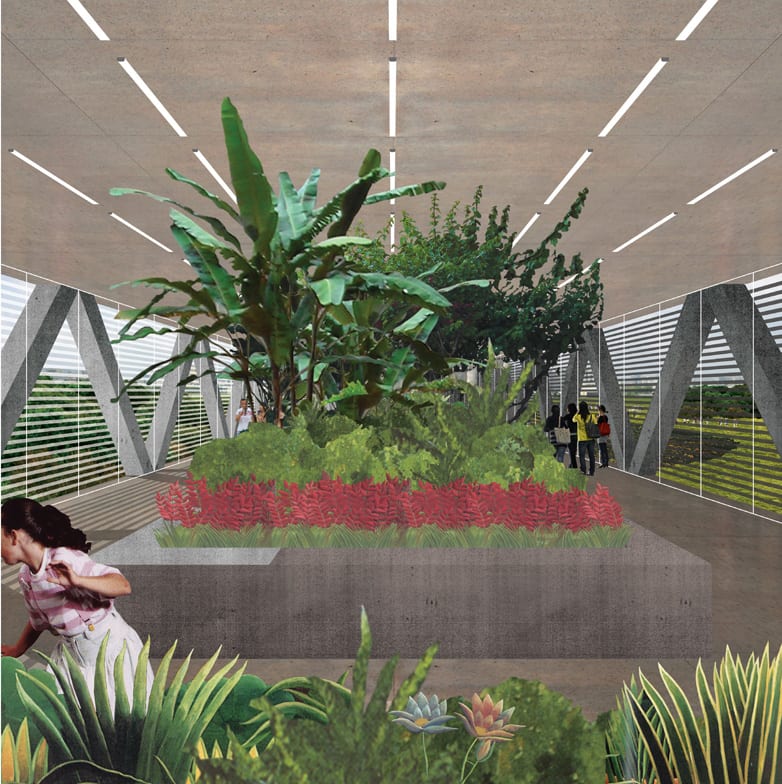

This entry proposed a park that combines non-figurative architecture with figurative signs and acknowledges that it is artificial and not an imitation of nature. It was open to the possibility of being developed in incremental stages.

As for an “Inhabitable bridge,” a monumental piece of architecture, elevated above the ground and running the length of the park and housing a variety of functions, the jury had mixed opinions about this element. Some found it a powerful statement, while other found it too closely resembled a transit bridge, an all too familiar feature of Taichung’s urban landscape.