Login to see more (login problems? E: scollyer@competitions.org or http://competitions.org/contact/)

|

|

||||

|

From Storied Restoration to Prime Time Destination

Winning entry ©Steimle Architekten

When we first included an article in COMPETITIONS about the restoration of Hannes Meyer’s Berlin Trade Union School in 2007, little did we anticipate that this subject would resurface on several occasions over the years. With the initial publication of

Contemporary Memorial Symbolism on the Thames

Image: © Adjaye Associates & Malcolm Reading Consultants

The recent U.K. Holocaust Memorial Competition in London concluded with designs from ten high-profile international firms . This began with a short-listing procedure which attracted expressions of interest from 97 international firms. In contrast to the entirely

This essay was published in The Architectural Competition – Research Inquiries and Experiences, Magnus Rönn, Reza Kazemian, Jonas E. Andersson (Eds.) Axl Books Stockholm, 2010 (pp. 578-600)

Introduction

The Vietnam War, 1959-75, was the longest and most divisive in American experience. 58,000 American soldiers died, 140,000 were wounded. Vietnamese casualties were far higher. The war caused permanent transformations in American society and culture. In 1979 Jan Scruggs, a Vietnam veteran, conceived the idea of a memorial to the memory of the American dead and, by implication, the veterans who had served. His further hope was that the memorial would reconcile the war’s veterans with the many Americans who had opposed the war. The memorial was to be sited in a place of honor on the Mall in Washington DC. It was to be privately funded as a citizen initiative, the federal government contributing the site. To undertake this effort a sponsor organization was created, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund (VVMF), its board members including West Point and Naval Academy graduates. Legislation to authorize a memorial, guided by Senators Charles McC. Mathias Jr. and John W. Warner, was passed by the U.S. Congress in May 1980 and signed into law by President Jimmy Carter in July. All public design projects in Washington are subject to intensive scrutiny, especially memorials. Three federal agencies, responsible for approving the design in all its aspects, were closely involved throughout the effort. Discussions concerning a design competition for the memorial had begun in May. Competition planning began in July. The formal competition process was concluded ten months later, in May 1981. The 1,432 designs submitted in the competition, a then record number, were judged by an eight-person jury, all professionals representing the principal design disciplines. The competition was won by a 21-year-old student at Yale University, Maya Ying Lin. The memorial was built and dedicated in November 1982, with a statue group and flagpole addition dedicated in November 1984, the latter the result of sometimes bitter controversy regarding the basic Lin design. The memorial became and remains one of the most visited in the U.S., having become a virtual icon. Much has been written about the design and the designer, and much attention was given to the controversy. Little has been written about the competition process itself, a process based on the highest standards for conducting design competitions. This paper focuses on that process, its context and its conduct.

Personal Perspective

My experience with competitions began in architectural school, where they are integral to the architectural design studio. Following school, studying and working in Italy and Sweden, 1954-56, my interest grew. In Italy I also became interested in contemporary memorials due to two examples related to WW II, both the products of competitions – the Ardeatine Caves near Rome and the Monument to the Deported in Milan. In Scandinavia that interest was broadened through studying the work of Gunnar Asplund, Sven Markelius, Alvar Aalto, and Arne Jacobsen – much of their work also the product of design competitions.

In 1955, on a visit to Sweden, I saw an exhibit of the competition entries for a proposed government center for Gothenburg. The winning entry was the work of Alvar Aalto. I was impressed by the simplicity and directness of Aalto’s drawings. His design, in my view among his most brilliant, was code named “Curia” in reference to a building in the Roman Forum. His submission was drawn in pencil on ordinary tracing paper. It included perhaps two or three constructed perspectives and photos of a massing model. The rest of his presentation consisted of plans, elevations and sections. Although this project was never realized the memory of the exhibit and the directness of Aalto’s drawings served as a guide in competitions that I later managed.

This general interest developed into the gradual realization that frequent and well-managed design competitions are a vital source for advancing creative design ideas. They are its exploratory test grounds. As important, they heighten the public’s interest and elevate public expectations of design, thereby establishing a vital environment for nurturing architectural creativity.

From 1966-70 I served as the first Director of Architecture and Design Programs at the then newly established National Endowment for the Arts, an opportunity that I used to try to promote their improvement and wider use in the U.S. In doing so I undertook an extensive study of competitions, historical and recent. I solicited the experience of architects from the US and abroad regarding their competition experience. I obtained and analyzed competition codes, mostly European and Scandinavian, but also the AIA code (destined to be withdrawn for legalistic reasons). Two products of my research were the book Design Competitions (McGraw Hill 1978) and, subsequently, the Handbook of Architectural Design Competitions (American Institute of Architects, 1981).

Unlike most European and Scandinavian countries, where the conduct of design competitions has been carefully regulated, in the US it has not. Although the federal government has had a limited program for certain “high profile” public buildings in recent years, in 1980 neither by the federal government, the constituent states, nor, least of all the AIA, the professional design organization of American architects, had any established and mandatory procedure for conducting design competitions. That condition has not basically changed. Conducting design competitions in the U.S. remains voluntary, entirely dependent on the sensibilities and skills of a project sponsor and the people enlisted to assist in it.

A sponsor of the requisite sensibilities proved to be the VVMF, who contacted the AIA for professional help. Since I was chairing the AIA’s committee on competitions at the time, developing the AIA Handbook, I was recommended to the VVMF as professional adviser. My first discussions with them were in May 1980. My work began in July, the same month that full authorization for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was procured. I worked directly with the VVMF Board and staff, but most closely with Robert Doubek, a West Point graduate and attorney.

Memorials and Competitions in Washington

Washington’s monumental character is the product of its 1791 baroque city plan and its largely neoclassic public buildings. That style also originates from the late 18th century. The earliest public buildings and monuments were products of design competitions — the U.S. Capitol, the White House, and the Washington Monument. Architect and later President Thomas Jefferson submitted seminal designs for the first two. Later works produced by design competitions include the Library of Congress, the Lincoln Memorial, and the Pan American Union. Inspired by Washington’s example, many of our individual states and municipalities utilized design competitions for their public buildings. One would think, then, that design competitions would be the norm for Washington, but that has not been the case.

In Washington, unfortunately, the practice became problematical. In the 1930s a design competition for a new Smithsonian museum, the winning design authored by Eliel Saarinen, had failed. The original effort to create a memorial to President Franklin D Roosevelt (FDR) through a design competition in the late 1950s had also failed. Other then recent memorials in Washington included the WW II Iwo Jima Memorial, a memorial to Senator Robert Taft, and the John F Kennedy Memorial. None were the result of design competitions. Beyond Washington there had been several recent and successful contemporary American memorial efforts, procured through open design competition, much esteemed by the general public. One was the Battleship Arizona Memorial in Pearl The Gateway Arch, St Louis. Gateway Arch competition drawing. Battleship Arizona Memorial, Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. FDR Memorial design, Washington DC. Harbor, designed through a competition won by a WW II Austrian refugee, Alfred Preis. One of the finest of all American twentieth century memorials is the Gateway Arch in St Louis (the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial), designed by Eero Saarinen. It was the product of a very well conducted design competition held in the late 1940s.

Apart from the inherent difficulty of creating memorials in Washington, competitions aside, an equally grave reality was that after 1975 the American public was trying to put the Vietnam War in the past, in effect to forget it. The veterans and their families could not. Thus, while the idea of a memorial to our Vietnam Veterans was most deserving, considering both the difficulty of making memorials in Washington and the critical factor of public support, there was little reason for optimism on our part.

Federal Design Approval Agencies

Three century-old Federal agencies are responsible for the approval for the design of public architecture in Washington. To create a memorial in Washington it is essential to coordinate carefully with them. The agencies are: the National Park Service (NPS), which manages public park lands and virtually all of Washington’s memorials; the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC), which approves land use and design; and the Commission of Fine Arts (CFA), which approves design. I had worked with all three. Their staffs were colleagues and friends. I knew their roles and responsibilities. Without compromising our work these agencies were involved on a working basis, mainly informational, from the inception of our effort.

Source of the Design Competition Methodology

A popular characterization of the predominant public architecture of Washington, most of it of classically inspired, is to refer to it as “beaux arts style”. In France, where the Institute of Fine Arts was founded centuries ago (l’Academie des Beaux Arts), and which included a school of architecture (l’Ecole d’Architecture) the term “beaux arts style” has no meaning. They would refer to Greek or Roman neoclassic precedents. Jefferson had introduced the idea of classical architecture to the U.S., inspired by his travels in France. From the 1870s until the depression of the 1930s many of America’s leading architects had studied at the Ecole. Because of the Ecole’s emphasis on neoclassicism and because so much American public architecture was neoclassic, the term “beaux arts” became an identifying style, a “brand”. This unfortunate misuse of the term obscures more significant aspects of the Ecole and its teaching methods. The Ecole is remembered for its extraordinary students drawings. Normally expressed with great graphic virtuosity the drawings were, foremost, exercises in developing a student’s design knowledge and facility, utilizing the most refined design palette of the western world. But Greek and Roman classicism were by no means all that they explored. Students also made detailed construction drawings. And they made designs for sites and climates far from the Mediterranean, even as far as Alaska, and so as different in architectural expression as the climates. Such exercises were far from neoclassic in motif. The Ecole was much more than a copybook of styles.

The Ecole was a school for learning how to design real and complex buildings. In the course of the nineteenth century France evolved into a Republic, and the Ecole’s students explored the possibilities for many novel types of buildings – schools, hospitals, and courthouses were typical subjects. Representative example designs accommodated many complex functions into a coherent workable form. The designs were depicted in plan, elevation, and cross section. Rarely did the students do perspective drawings. Their drawings, consisting of the three-part plan-section-elevation depiction system, had to be analyzed by the viewer for all their implications – appearance, function, structure, circulation, construction feasibility, spatial experience and hierarchy, visual emphasis, light, ventilation, etc. The artistic virtuosity demonstrated in the drawings can obscure the underlying purpose of architectural depiction in plan-section-elevation. Unlike perspective renderings, whose purpose is largely to allure, the purpose of depiction in plan-section-elevation is to inform. In order to be understood such drawings must be examined analytically, like a physician analyzing an x-ray. Thus the concomitant to this method of depiction is that it requires expert and experienced eyes to evaluate. It requires jurors of long experience and extensive expertise. In a large array of designs, as in a competition, the normal condition in the Ecole, jurors had to be capable of evaluating a design rapidly, to see the essence of an idea at a glance. Plan-section-elevation depiction also puts all design submissions, as in a competition, on an equal basis of comparison, one design with another. Thus, the cornerstone of an effective design exercise and its proper evaluation, certainly for a competition, was and remains clear and fully informative depiction on the one hand and evaluation by expert jurors on the other. The Ecole’s depiction method was disseminated world-wide, wherever competitions were held, and it persisted after the demise of the Ecole in the 1960s. It continues today. It has persisted because it is a very good idea. Not surprising, then, are Eero Saarinen’s original very good idea. Not surprising, then, are Eero Saarinen’s original competition drawings for the St Louis Gateway arch —plan-section-elevation—the same technique used in the Ecole.

Construction drawing, L’Ecole d’Architecture.

Project in Alaska, l’Ecole d’Architecture.

Looking southward into the memorial site.

Looking eastward from the memorial site to the Washington Monument.

True, Saarinen included a widely published perspective, but that was an accompaniment. The St Louis compe-tition brief required the traditional and proven depiction triad.

The Memorial Site

The site for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, chosen with the guidance of NPS, was a small and quite inconsequential western corner of Washington’s central Mall, its monumental core. The selection of this site had been made by July 1980 when I was engaged as professional adviser. I concurred fully with the choice, feeling that if it were not possible to make a suitable memorial there it would not be possible to make one anywhere.

The site was a two-acre (0.8 hectare) area, a rough circle in form, 1000 feet (300 m) northeast of the Lincoln Memorial. To its east was an artificial pond called Constitution Gardens. To its south stood a row of neoclassic buildings of modest scale. The site itself was a quiet tree-lined meadow. Its special character, however, derived less from its interior, even less from what one saw looking into it, as what one saw looking out of it — looking from it. From the site one could see, principally, a striking view of the 555 foot high (169 m) Washington Monument 0.7 miles (1,120 m) to the east. To the southwest was a view of the Lincoln Memorial. The Washington Monument vista, unobstructed by trees, was clear throughout the year. The Lincoln Memorial vista is fully clear only in winter, when it is not obscured. Lesser vistas were of the US Capitol dome and several Smithsonian Institute landmarks buildings on the Mall. But the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial were the main vistas, giving the site its special value.

Competition Planning and Execution

Living on the Pacific Rim can be a risky business. In L2010, Christchurch, New Zealand suffered a devastating series of earthquakes, resulting in the virtual destruction of half of the city’s urban fabric in the downtown area, the destruction of 100,000 homes, and the deaths of 185 of its inhabitants.

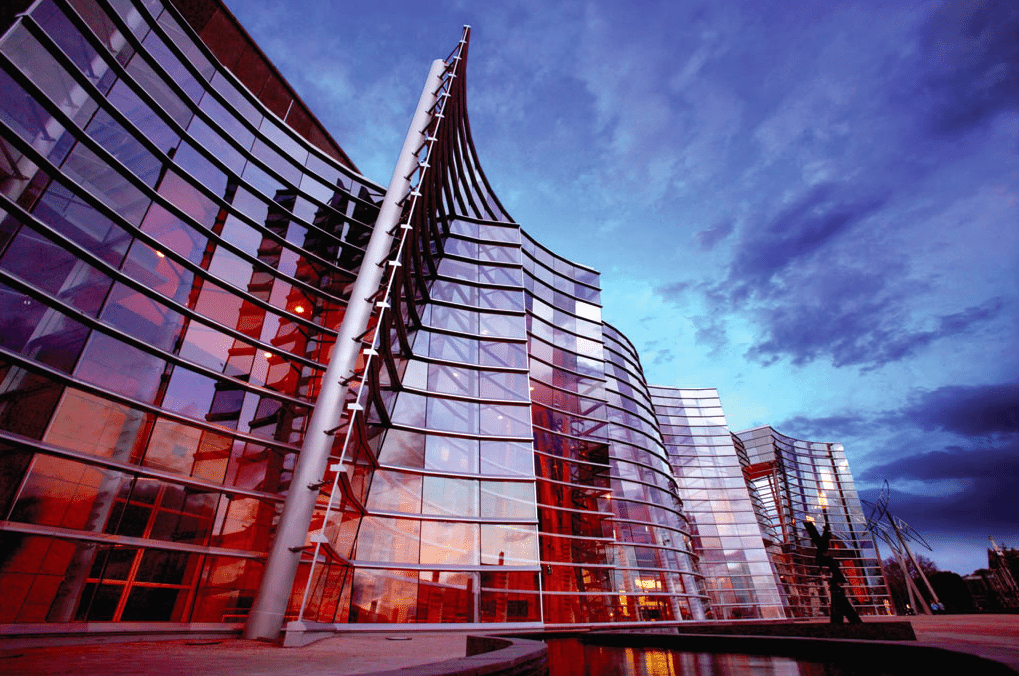

When we first heard of this disaster, one of our concerns was the survival of the new Christchurch Art Gallery, a stunning modern structure, which was the result of a 1998 design competition won by the Buchan Group of Sydney.* Based on the success of that competition, and its strong support by the local populace, using a similar process to select a design for a memorial to commemorate the victims of this disaster would have seemed to be a logical strategy.

For residents of Louisville, Kentucky, it would come as no surprise that the city’s Vietnamese community would support a competition commemorating the friendship and support of the Americans both in Vietnam and the U.S. and our welcome for the Vietnamese people who have arrived in this country. The foundation established to realize this concept was named “Tri An,” which means “deep gratitude.” According to the competition brief, “It is important to recognize the numerous humanitarian efforts and good deeds done by the U.S. military and the many Americans who went far beyond the call of duty to help the South Vietnamese people. As is the case with many non-government supported projects, this one also had a patron who lent his support to project, Yung Nguyen, the local founder and patron of the Tri Ân foundation, also the founder of a high-tech firm. To administer the competition, the foundation engaged the services of a local architecture firm, Bravura, which had a notable track record in memorial competitions, having previously acted as professional adviser for the acclaimed Patriots Peace Memorial competition in Louisville. In setting the bar for the anticipated winner, the competition brief stated that the design:

To attract the widest possible audience, the organizers decided on an international, open and anonymous, two-stage competition as the best model. It was decided to award three finalists the opportunity to have their designs equally reviewed for the possible realization of the project in a second phase. For their efforts, each was to receive compensation of US $4,000.

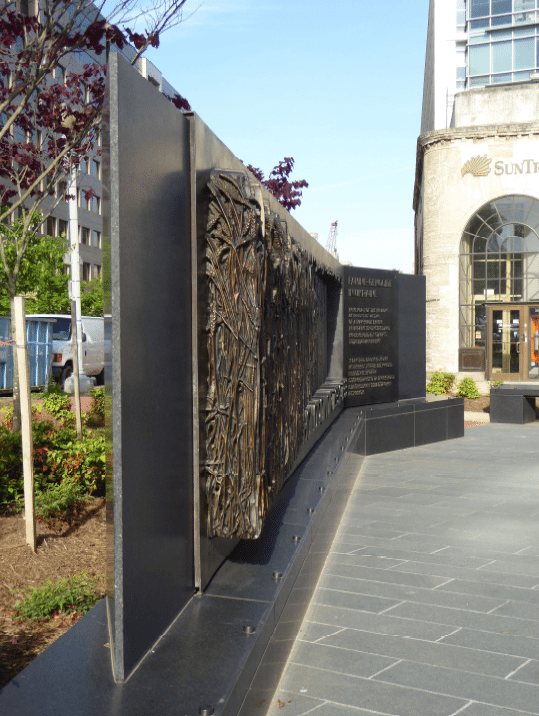

The Holodomor Memorial competition, held in 2011 in Washington, DC, was covered by this author in an Ezine from January 7, 2012 (http://competitions.org/2012/01/the-holodomor-memorial-competition-commemorating-ukrainian-famine-victims-under-communist-rule/?preview_id=17540&preview_nonce=ad77b76eb3&_thumbnail_id=-1&preview=true). Completed in 2015, and taking a symbolic page from Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the Mall, it commemorates those Ukranians who perished during the Stalin-era collectivization of agriculture in the Ukraine. Contrary to the Vietnam Memorial, there would have been no opportunity to list the million or so victims of that tragedy on this memorial. Across from Union Station, this high visibility site will provide not only a place of contemplation for victims’ families, but provide many visitors with a quick flashback to one of the world’s worst examples of genocide. –Ed.

DESIGN STATEMENT Larysa Kurylas, Design Architect & Sculptor “FAMINE-GENOCIDE IN UKRAINE: IN MEMORY OF THE MILLIONS OF INNOCENT VICTIMS OF A MAN-MADE FAMINE IN UKRAINE ENGINEERED AND IMPLEMENTED BY STALIN’S TOTALITRIAN REGIME.”

Thus reads the dedication panel inscription on the Holodomor Memorial, recently completed in the heart of Washington, DC, to ensure that this horrendous but little known 1932-33 genocide is never forgotten . . . and never repeated anywhere in the world. The focal point of the Holodomor Memorial is a bronze, bas-relief sculpture titled “Field of Wheat.” Wheat is the theme not only because its confiscation led to the death of millions of innocent Ukrainians, but also because wheat cultivation is one of the few things that Americans associate with Ukraine. The bas-relief depicting the field of wheat is subtly perspectival. From left to right across 30 feet, highly articulated wheat heads and stalks initially project outward from the rectangular, bronze wall plane, then gradually recede into the wall and finally, as the recess steadily deepens on the right, fade away completely. “HOLODOMOR 1932 – 1933” emerges at the base of the receding wheat stalks. The entire bronze wall rests on a granite plinth that deepens as the site slopes down to the west. Thus the dynamic, three-dimensional sculpture symbolizes transition from harvest bounty to food deprivation. The negative recessive space of the sculpture conveys the willfulness and cruelty of the famine, motivating viewers to contemplate the inhumanity of using wheat as a political weapon in what was once the “Breadbasket of Europe.” The sculpted “Field of Wheat” is within arms reach, encouraging personal, tactile engagement with the memorial through touching and burnishing of the bronze surfaces. The sculpted wall responds to the L’Enfant plan geometry of the site, reflecting the diagonal of Massachusetts Avenue and the grid of F Street, although the basrelief faces Massachusetts Avenue, the more important street. Being nearest to the triangular site’s widest, western end distances the sculpture from the busy, noisy convergence of North Capitol Street, Massachusetts Avenue and F Street, while framing a memorial plaza paved in furrowed slate with a linear texture evocative of barren plowed fields.

Because of the sculpture’s placement and low, horizontal profile, Massachusetts Avenue’s historic sight lines are preserved. This design strategy also ensures that the memorial is perceived as appropriately restrained in character. Granite panels attached to the back of the bronze sculpture face F Street and mediate between the Holodomor Memorial and sidewalk cafes across the street. A geometric pattern etched on the panels derives from a folk-inspired design by Vasyl Krychevsky in 1933. Abstractly suggesting barbed wire, the design symbolizes the attack on Ukrainian culture – a parallel goal of the Holodomor – and alludes to the Ukrainian border deliberately sealed by the government at the peak of the Holodomor. A wide brick walkway connects the memorial plaza to the F Street sidewalk. Between the sidewalk and the wall, staggered native Forest Pansy purple-leafed redbud trees form a distinctive backdrop for the “Field of Wheat” sculpture. Two native types of Nandina Domestica shrubs, selected for hardiness and yearround visual appeal, are interspersed among the trees and occupy the rain garden — designed to capture all storm water runoff — at the western edge of the site. The shrubs’ white flowers and red berries are reminiscent of “kalyna,” so prominent in Ukrainian folklore. In the positive-to-negative sculpting of the “Field of Wheat” and the composition of human-scale elements sweeping horizontally across the triangular site, the intent was to create a subtle yet powerful work of commemorative civic art in remembrance of the millions of victims who perished in the Holodomor. This evocative memorial enables contemplation by one person, a few individuals or a group of people. How inspiring it would be some night to see hundreds of flickering candles reflected on the wall, with a gathering of people solemnly singing “Vichnaya Pamyat” – “Eternal Memory.”

CREDITS Agency Sponsor: National Park Service Memorial Sponsor: Government of Ukraine Memorial Advisor: U.S. Committee for Ukrainian Holodomor–Genocide Awareness, 1932-33 Architect-of-Record: Hartman-Cox Architects Design Architect: The Kurylas Studio Sculptors: Larysa Kurylas and Lawrence Welker IV Foundry: Laran Bronze, Inc. General Contractor: Forrester Construction Company

NATIONAL HOLODOMOR MEMORIAL, Washington, DC (dedicated November 7, 2015) Photo: ©Larysa Kurylas

The Holodomor Memorial competition, held in 2011 in Washington, DC, was covered by this author in an Ezine from January 7, 2012 (http://competitions.org/2012/01/the-holodomor-memorial-competition-commemorating-ukrainian-famine-victims-under-communist-rule/?preview_id=17540&preview_nonce=ad77b76eb3&_thumbnail_id=-1&preview=true). Completed in 2015, and taking a symbolic page from Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the

Martin Luther King Memorial Competition Washington, DC (volume 10, number 4– Winter 2000) click to view larger image Winning Design ROMA Design Group San Francisco, California click to view larger image First Runner-Up Kohn, Pedersen, Fox New York, NY click to view larger image Second Runner-Up Brooklyn Architects Collective New York |

||||

|

Copyright © 2024 Competitions All Rights Reserved Competitions, Ph: (502) 792-2088 Website: https://competitions.org E: stanlycollyer@gmail.com Privacy Policy: Privacy Policy Cookie and Consent Policy: Cookie and Consent Policy Terms of Service: Terms of ServiceDisclaimer: Disclaimer IMPORTANT NOTICE : Unless otherwise indicated, photographs of buildings and projects are from professional or institutional archives. All reproduction is prohibited unless authorized by the architects, designers, office managers, consortia or archives centers concerned. The Competitions-Archive LLC is not held responsible for any omissions or inaccuracies, but appreciate all comments and pertinent information that will permit necessary modifications during future updates. |

||||