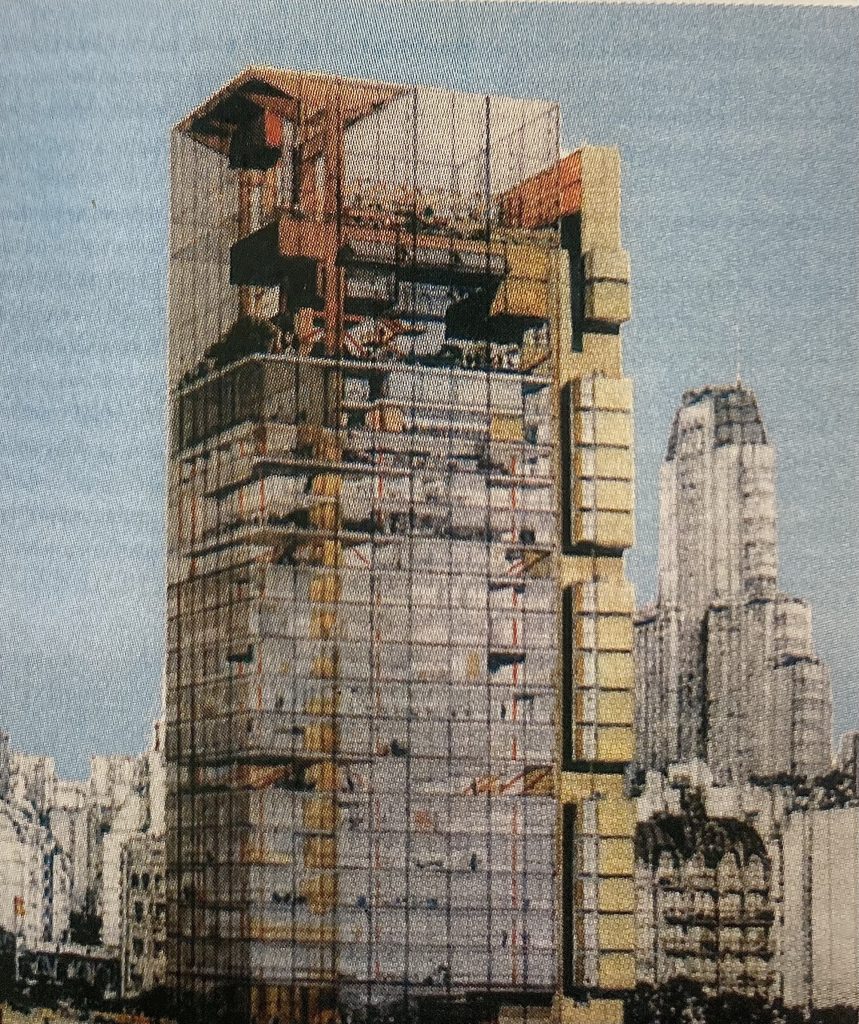

Figure 1 Industrial Union Tower (1967)

Rafael already made a name for himself in the late sixties as a university student in Buenos Aires. While I was a student serving as an intern in a downtown office in Buenos Aires, one of my peers came back with a story about an incident during his university exam on the ‘History of Modern Architecture’. We were all anxious about his fate, since that was one of a trilogy of final exams at the UBA for architecture students, and you could never be sure, if after eight years or sometimes more, whether you would pass or not.

According to my friend, It was an easy ride; but apparently it wasn’t for Rafael Vinoly, who also was to graduate at that time, and apparently had done anything but ace that test.

“All of a sudden Rafael started lecturing his examiner on architecture, the avant garde and politics. It was then that his professor invited the rest of the faculty to join him. They all listened in awe, as did we students as well. His exam closed with extended applause.” That applause was a scandal for a school such as ours, in the recent shadow of a military junta that governed with an iron fist.

From that day on, Rafael’s name always came to me associated with excellence, as well as his charming tales about the world of architecture. His majestic perspective for the Industrial Union Tower Competition (Figure 1) that unquestionably won the first prize in that competition made him, as young as he was, a “primus inter pares” at the top of his office’s creative staff. Aside from the commission for the City of Buenos Aires Banks that the office had generated through traditional connections and marketing, this was the firm’s first great achievement and looked as if it was all his.

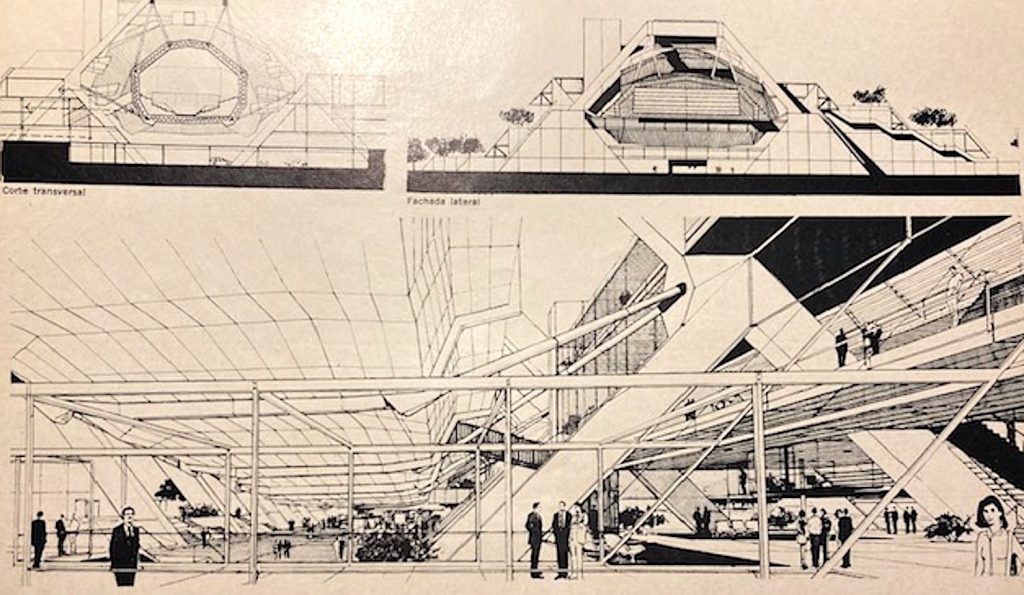

Figure 2 Buenos Aires Auditorium (1969)

Such recognition made him the lead on the competition for the Buenos Aires Auditorium (Figure 2) that did not end well. An observer that was allowed entrance to the typical restricted area of the competition projects asked why the office had decided to take the risk with these two huge violins that had little chance.

One of Rafael’s senior partners replied: “We have to let ‘The Kid’ play.”

A major opportunity occurred when the military was unable to fight Eduardo Sacriste, a sort of Argentinian version of Jane Jacobs, who relentlessly attacked the Mayor for the design of the TV Center for the 1978 Soccer World Cup—a design low point for the military government. Sacriste (one of the member architects of the Beaux Arts academy) had sunk before, the project for the German Embassy designed by Walter Gropius and Amancio Williams and in the same park that was been used now for the TV center.

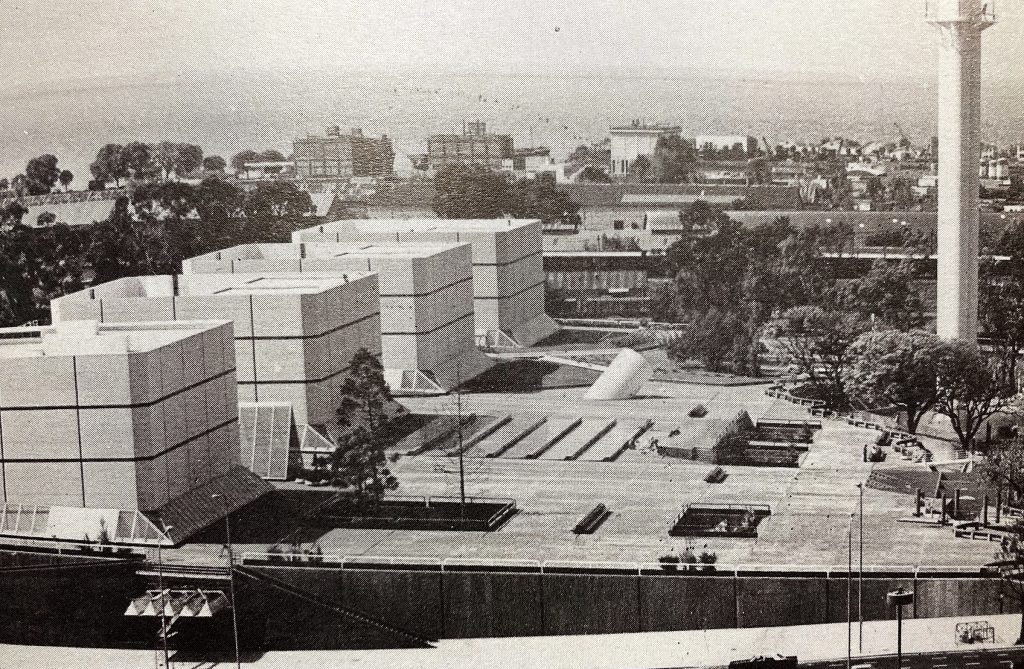

Figure 3 Buenos Aires TV Center and park

History tells us that 18 months away from the opening, with a pancake like project using a good part of Sacriste’s well guarded public park, Vinoly suddenly inclined the building model, creating a huge garden terrace that was to be for several years the parks most successful playground. Voila! (Figure 3)

His vibrant energy followed the project up to the details, and he was seen on the floor, almost obsessed selecting the color palette. The myth of the brave Enfant Terrible of Latin American architecture was reborn.

I met him for the first time in Berlin during a small IBA conference organized by Joseph Kleihues and Jorge Glusberg. It was a busy schedule, so much to see and do. At the time of departure the group met in the hotel lobby. All was very vocal, commanded by Vinoly‘s noisy and expansive good humor.

I mentioned to him I was going back via NYC, and in a typical inquisitive Buenos Aires style, he asked me about myself. He started laughing when I told him that I was Sacriste’s partner for some competitions and articles. “Ohhh, I see…You are a Pedigree boy!!! Call me. Let’s have breakfast in my office, 65 Bleecker St., Sullivan’s only building in New York.”

Two days later, he walked me around the office and when I mentioned how large it was, he started shouting all around like a mantra: “It has to be larger, it has to be larger”. In that happy Berlin farewell he had taken the challenge tossed by one of his former associates:” Rafael hope you can redesign some NYC lobbies”. Obviously the seed of competition that was planted with his departure from Buenos Aires was still alive. He had to wait a few years for revenge, as harsh as it sounds, is in this case was absolutely valid in Buenos Aires competition jargon.

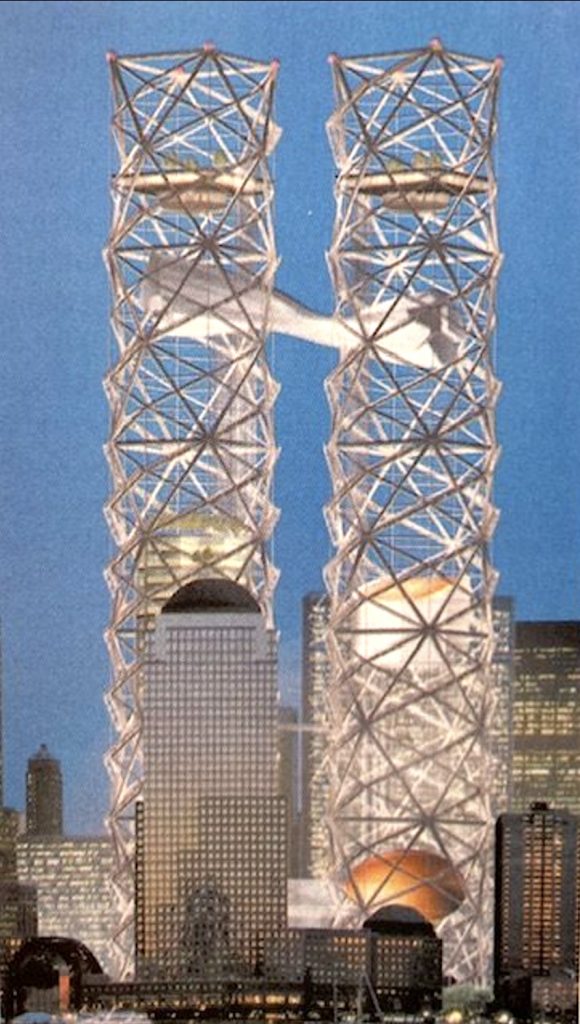

The Tokio Forum (Figure 4) was the vehicle for an extraordinary success, a remarkable achievement (Figure 4), but that was not going to win the Pritzker. Had the Forum had the luck of Hollein’s Münchenglatbach, maybe Vinoly’s interests would have changed, guiding his career in a different path. The Twin Towers project as part of the “Think” team at Ground Zero (Figure 5) (in my humble opinion by far his best), unfairly questioned at the time, was not to be either.

Figure 5 Think team World Trade Center competition finalist proposal (2003)

David L. Lawrence Convention Center, Pittsburgh; Competition (1999), Completion (2023)

We met again, while having lunch with Franco Purini at the Venice Bienale Arsenale. He joined us immediately, and made us laugh with his witty, sarcastic comments. So much joy!!! So much life!!!

When lately involved in the design of a large urban project, I thought of both of them for a design team. Knowing that Franco Purini was on board, I turned to an RV associate in Buenos Aires, but finding little knowledge of the US milieu, I asked his friend, the developer of Punta del Este’s Aqua building to schedule a meeting, which was set to happen in June. His sudden death deprives world culture of a phenomenal talent, thinker and doer. The Enfant Terrible of Latin American architecture, Uruguayan by birth and Argentine by education, will be missed on both banks of the River Plate.

Carlos Casuscelli, who received his education in architecture in Buenos Aires—at a time when Rafael Viñoly was also still there—was also a successful architect in Buenos Aires before immigrating to the U.S. during the years of political upheaval in Argentina. After a teaching tenure at Ball State University, he moved to Miami, where he and his wife, Mariana, also an architect, have a successful design studio.

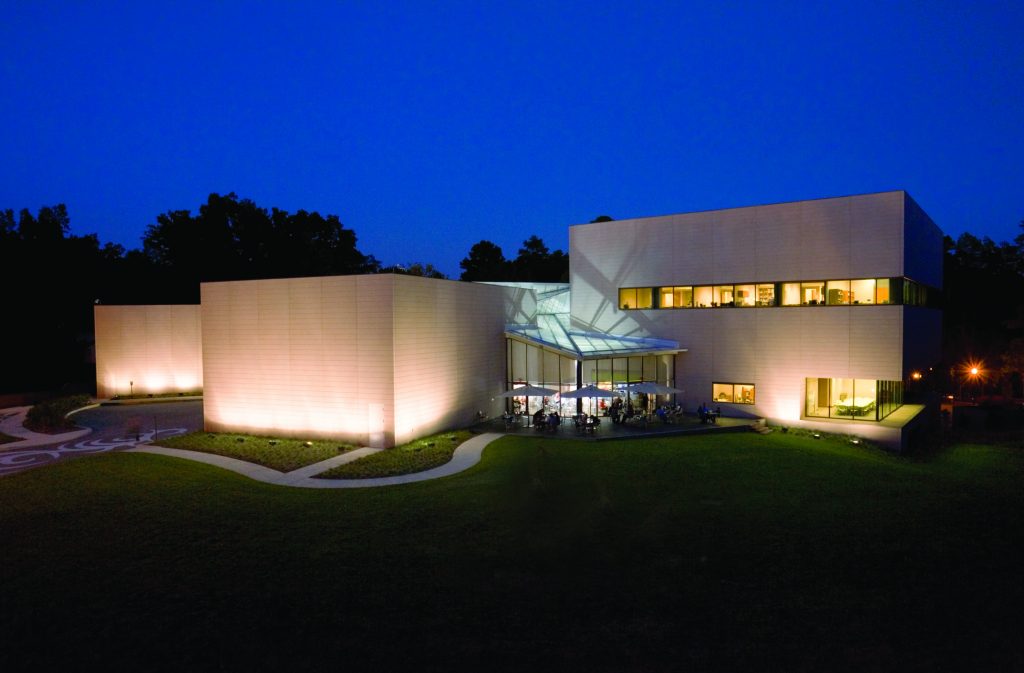

The following photos from Viñoly’s Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University (2005) were included in this article as one of the editor’s more interesting choices of projects from the Viñoly portfolio.

Unless otherwise noted, above photos: courtesy Nasher Museum of Art