Richard Rogers (1933-2021)

Could you imagine that a person who is anything but adept at drawing, and also dyslexic, would become one of the world’s great architects? Meet Richard Rogers, who was full of ideas, but engaged collaborators to fully realize them. One might even assume that Rogers choice of architecture as a profession was logical.

Roger’s cousin, Ernesto Rogers, was not only an important Italian architect, but as renowned journalist, editor of two Italian architecture magazines, the most notable being Casabella, where he used the term, “Rationalism,” as pertaining to architecture. So for Richard, born in Florence, Italy, who fled with parents to England in 1938 as refugees from the fascist Mussolini regime, the architectural pedigree was already well established in the family genes.

London’s Architectural Association was his introduction to academia and the first step up the ladder toward finding his niche in the profession. That was eventually followed by studies at Yale in the U.S. and encounters with a number of important architects, including Paul Rudolph and, most importantly, Louis Kahn, the latter imparting to him that all important advice: work collaboratively.

Pompidou Centre Photo ©Stanley Collyer

Returning to London, he and his wife, Su Brumwell, together with Norman Foster and his wife, Wendy Cheesman, established a firm called Team 4. Then, in 1970, Rogers entered a practice with Renzo Piano, the result of which was the winning entry for the Pompidou Centre design competition in 1971. Although at first reluctant to enter that competition, once their design won and was built, there can be little doubt from what came later in his own practice, that his finger prints could well be observed as one of the driving forces behind the hi-tech design through the ultimate realization of that project.

Lloyds of London Photos © Richard Bryant, courtesy of RSHP

Encountering a ground-breaking project like the Pompidou Centre, one’s first inclination is to find out more about the architects. In the case of Rogers, that was subsequently easy to learn—a 1986 biography by Bryan Appleyard went a long way towards serving that purpose. More important was Rogers own book, authored with Mark Fisher, A New London. There he discussed the shortcomings of the institutions that commissioned architecture in England, stating that almost all of the interesting architecture built to that date was the result of private clients, not from government support. His next major project, the Lloyds of London headquarters in downtown London was a case in point. If anything, that building made yet a stronger statement about high-tech than the Pompidou. When visiting London, I was told I should go visit Rogers’ Channel 4 building. Another hi-tech production, it was located in an older neighborhood, where it had a commanding street corner presence.

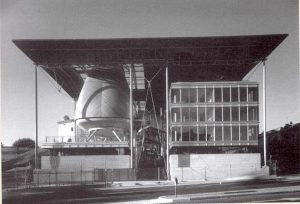

Bordeaux happened to be on the way from Paris to Bilbao, Spain, where I would visit Gehry’s new museum. The stop in Bordeaux turned out to be just as rewarding. Rogers’ Courts building I visited there turned out to be an eye-opener. Although an extension of the existing courts, at first glance one would never have guessed that. A whimsical building with suspended pods of wood serving as courts, there was absolutely nothing threatening about the structure’s design. A thought crossed my mind: if all courts had such a calming effect, might not there be less crime, or at least less harsher sentencing?

La Defense competition Photo: Stanley Collyer

Richard Rogers was one of the jurors that chose von Spreckelsen’s winning design in this Paris competition

In his 1992 book about London’s shortcomings when it came to new architecture, he discussed the European model, depending heavily on competitions as a vehicle to achieve better design. He discussed Mitterand’s Grande Arch de La Défense competition at length, won by the Danish architect, Johann von Spreckelsen. As a member of that jury, Richard was making the rounds of the entries, discussing them with juror, Richard Meier. Another juror who was tagging along, Jorge Glusberg, remembered the following episode while they were examining what turned out to be that final winner, but, from its presentation, obviously not from a high-profile firm.

Richard Rogers to Meier: “Richard, this person could be a nobody.”

Richard Meier: “Richard, before the Pompidou, you were a nobody.”

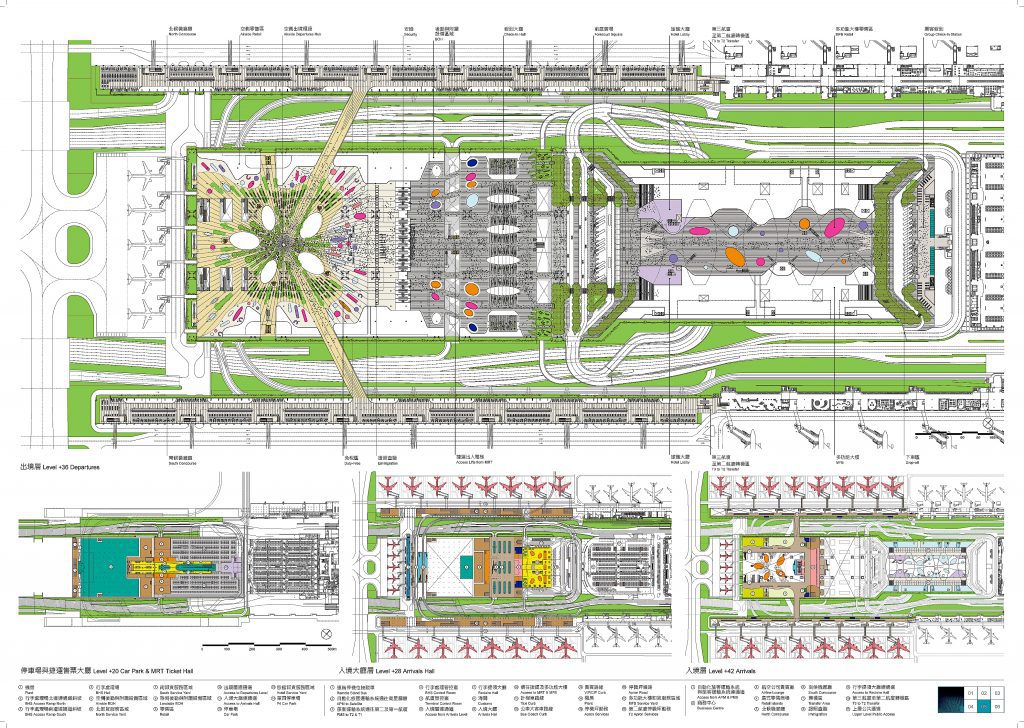

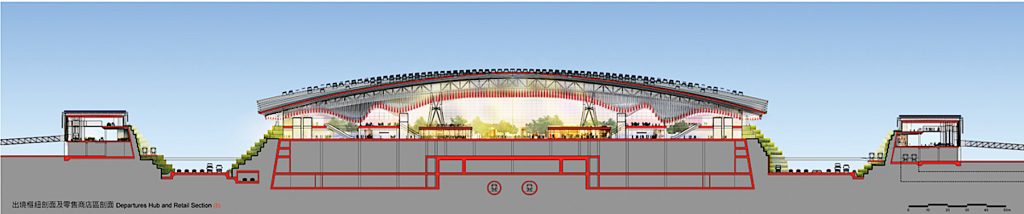

Frequent international travelers have no doubt experienced an airport designed by RSHP, the most important to date being Heathrow Terminal 5 (London) and Madrid’s Barajas Airport Terminal 4. One of the world’s largest airport terminals in Taiwan is the result of an invited competition RSHP won over Van Berkel en Bos U.N. Studio and Foster and Partners. Now under construction, it should be open by 2023.

Images from Rogers Stirk Harbour’s winning Taiwan Taoyuaong Terminal 3 competition presentation (2014-)