by Stanley Collyer

Contrary to previous autocratic regimes in Russia, the current visual arts community is apparently encountering few restrictions and is evidently regarded by authorities as being essentially apolitical, presenting no danger to the system—Socialist Realism is out; abstract art is in. This expansion of accessibility to contemporary art collections is attested to by the recent competition for a new National Center for Contemporary Arts in Moscow, also supported by the local Moscow administration.

Besides appealing to the local populace, there could be little doubt that the sponsors were looking for a Bilbao effect, as a lure to potential foreign tourists. During the Soviet period, contemporary art was not a cultural priority, and artists such as the deconstructivists were sidelined. Now may we see more missing examples from the early modern period in Russian art?

Similar to recent practices in the EU, this open international Competition was held in two stages. During Stage 1 the jury selected ten participants: five from the candidates who filed qualification applications containing all the necessary information about the participants, and five from the candidates who developed preliminary architectural concepts for the museum. In Stage 2 the teams received the competition brief to develop their architectural concepts. Based on that, the jury selected three finalists.

The ten firms shortlisted for the Second Stage were:

- UNK Project (Russia)

- WAI Architecture Think Tank (China)

- Anton Barklyanski (Russia)

- Melorama (Russia)

- Ghirardelli Giancarlo Architect (Italy)

- Steven Holl Architects (USA)

- Nieto Sobejano (Spain)

- Heneghan Peng (Ireland)

- 51N4E (Belgium)

- Alejandro Aravena (Chile)

Determining who the five shortlisted firms were, based on their portfolios, is probably not rocket science. Those above-numbered firms 6 through 10 could easily be viewed as the ‘usual suspects.’ Therefore, we can probably assume that only one participant from the ‘non-prequalified’ group made it to the final group of three—MEL. In the end, Heneghan Peng of Dublin, also winner of the Egyptian Museum competition, was declared the winner.

The Jury

The sponsor assembled an international jury, consisting of curators, museum and art institution directors, and architects, including Maria Baibakova, Director and Chief Curator, BAIBAKOV art projects, Russia; Bart de Baere, Director, Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst Antwerpen (MuHKA), Belgium; Louis Becker, Principal, Partner, Henning Larsen Architects, Denmark; Dieter Bogner, Founder of Vienna’s “Museum Quarter” and owner of Bogner-cc, Austria; Manuel Borja-Villel, Deputy Vice-President of the Fundación Museo Reina Sofía, Spain; Giovanna Carnevali, Director, Mies van der Rohe Foundation, Spain; Sergei Kuznetsov, Chief Architect of Moscow, Russia; Leonid Lebedev, Member of The Council of the Federation of the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation; Mikhail Mindlin, Director of The National Centre for Contemporary Arts, Russia; Nikolai Shumakov, President of The Union of Moscow Architects, Russia; Sergey Tchoban, Managing partner, Architectural Bureau «SPEECH Tchoban & Kuznetsov», Russia.

The Design Challenge

The site for new building of the National Center for Contemporary Art was in Khodynskoye Pole (Moscow), a former airfield at some distance from the center of the city. The site was an unlucky one, since a shopping center was in the process of construction to the rear of the site while the competition was taking place. Had the shopping center been integrated into a total plan, a better result, and one less awkward, might have been anticipated.

The brief stated that this facility should become “the main national institution and a focus for all possible ventures in the sphere of contemporary art. These include young artists’ projects and luminaries’ exhibitions; the Center’s own collection and those of other institutions and private collections; the Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art and the National Contemporary Art award; open lectures and movie shows; professional conferences; publishing programs and an e-library; concerts and performances; an art school for children; artists’ studios; a café and a bookstore, etc. Entering the Center, every visitor must feel not just as if he were in Moscow or Russia but in a Center of Contemporary Art on an international scale, a significant point on the map of the museum world.”

“It is to be an institution with a developed museum infrastructure (a cafe, a club, a bookstore and gift shops, a room for children’s activities, etc.), a research center and an educational program, the purpose of which is to familiarize a wide range of visitors — Muscovites and tourists, children and adults, those with previous experience of such art of those without — with the art of the past decades and excite interest in this sphere of world culture.”

The Entries

As might be anticipated, the competition attracted a variety of designs—cubes (MEL, Wai Think Tank), verticality in the form of towers and layered programs (Heneghan Peng, Holl and and Aravena), and massive facades with penetrations at the surface (UNK Project, Ghiradelli). What one did not find was any reference to the sweeping, poetic statements of a Fuksas or Zaha Hadid. In retrospect, the committee might have considered their architectural expression too predicable for this design exercise. What was more interesting was the effort by the finalists to establish a connection between their architecture and the place.

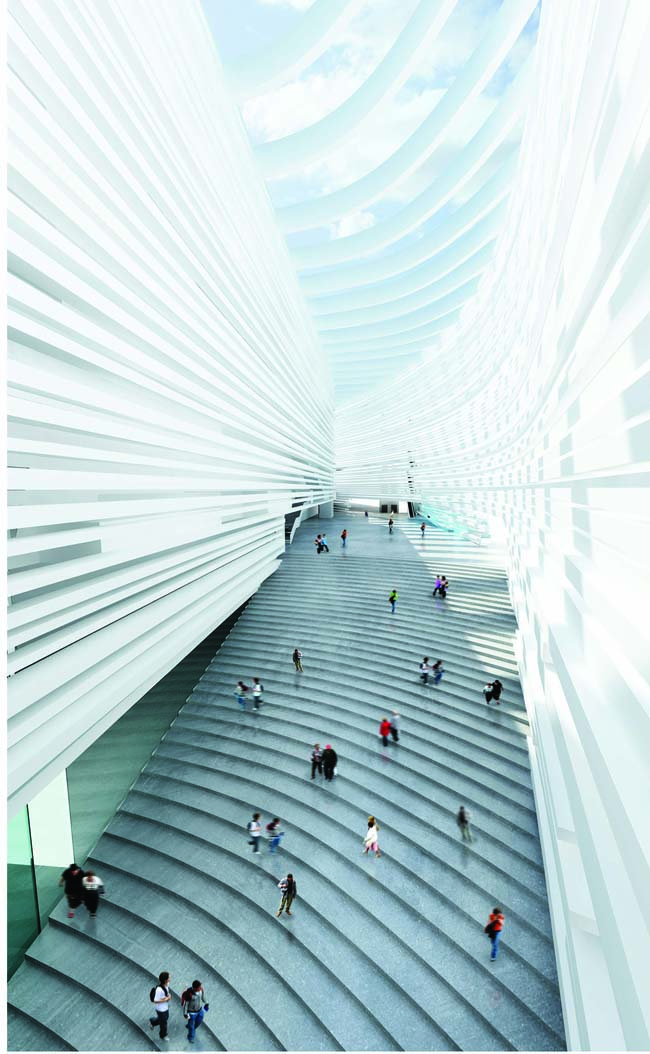

First Place – Heneghan Peng (Ireland)

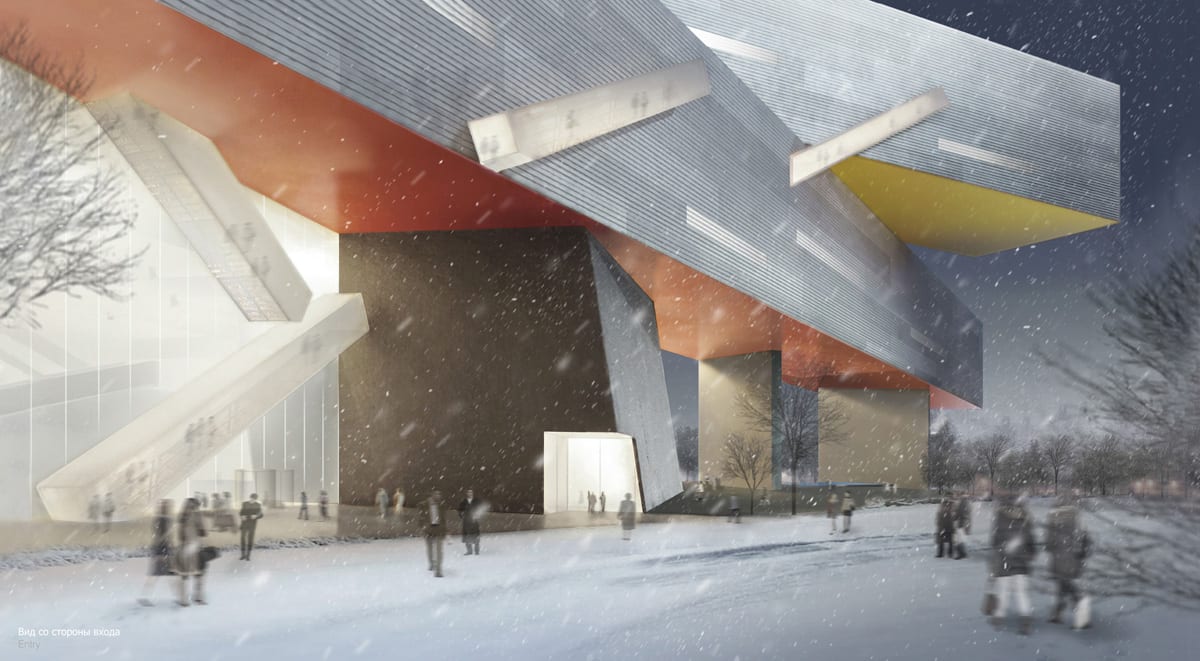

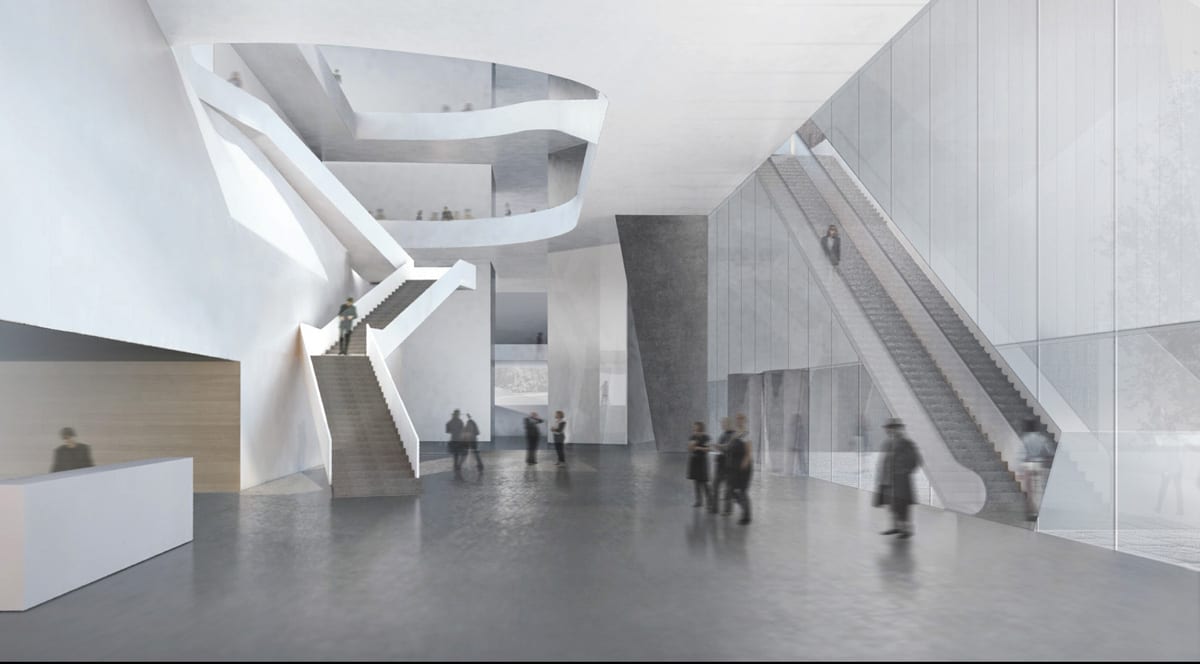

The architects address the verticality of this structure with cantilevered “trays,” adding a significant visual feature to the building, which lends it a commanding presence in the center of the site. By creating this strong central focal point in the center of the site, the new shopping center to its rear can serve as a backdrop, rather than an item to be covered up horizontally, as we see in many of the other proposals Functionally, it told visitors that their experience would be a shorter vertical one, rather than a longer journeys throughout exhibition spaces at grade to reach their destinations. The exhibition areas were concentrated on the upper levels, thereby providing visitors with a view of the entire workings of the museum as they ascended via escalator. This stacking idea is vaguely reminiscent of SANAA’s New Museum in New York, also a vertical experience, though Heneghan Peng’s is more pronounced in defining each level by featuring the cantilevered trays. However, the NCAA Museum has more room to spread out, contrary to the New Museum, where the constrained site dictated its verticality—the slight offset of each level lending an important visual effect. Although this may have not had anything to do with the jury’s final decision, it should be noted that one of the jurors, the Austrian Dieter Bogner, is on the Board of the New Museum.

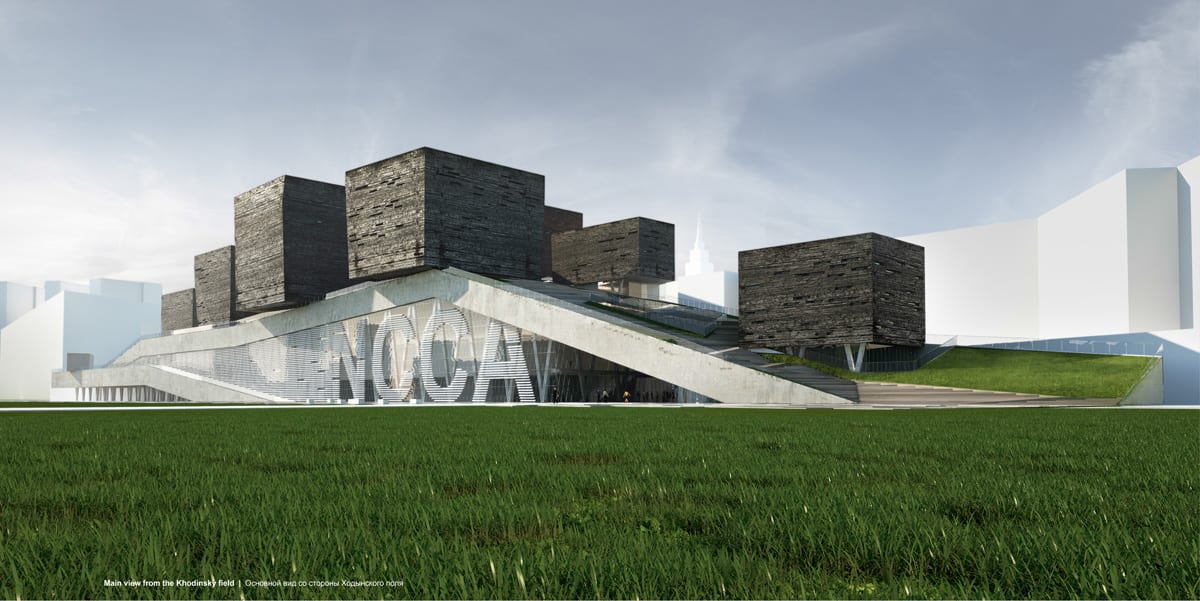

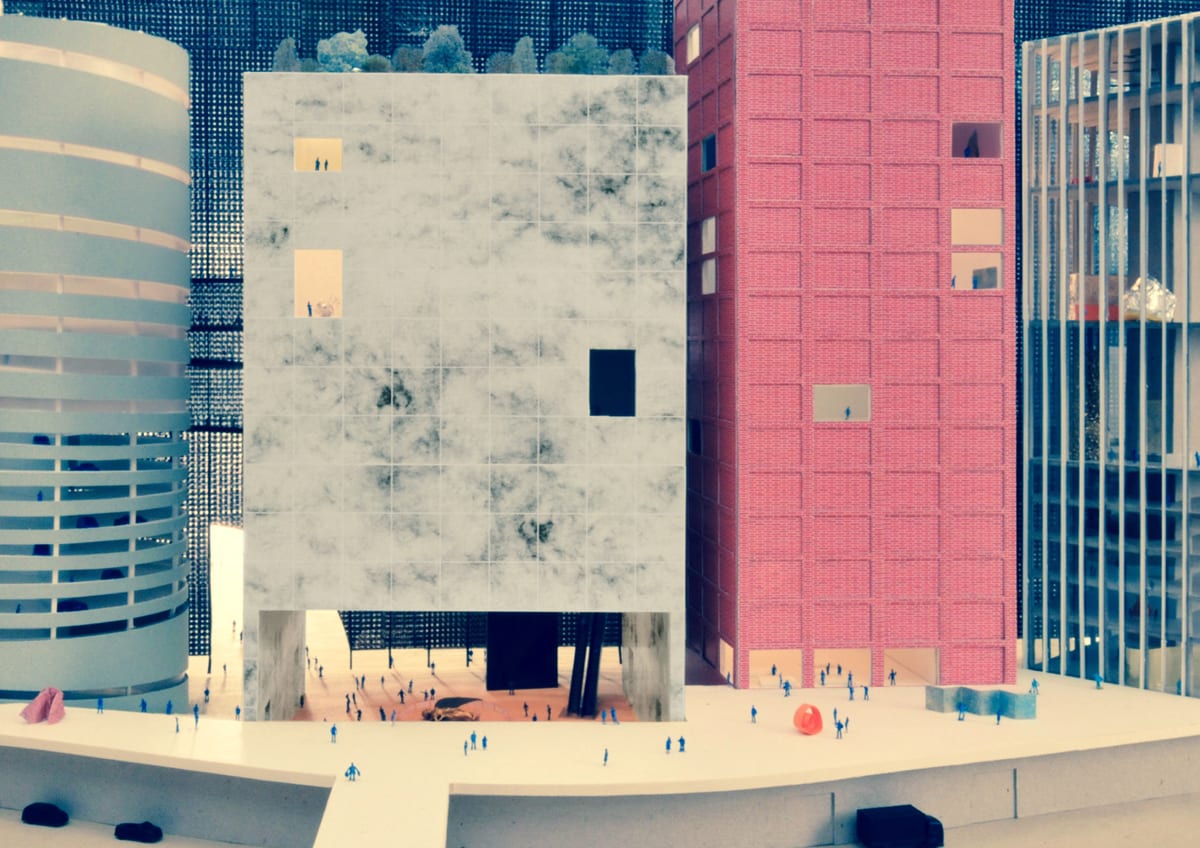

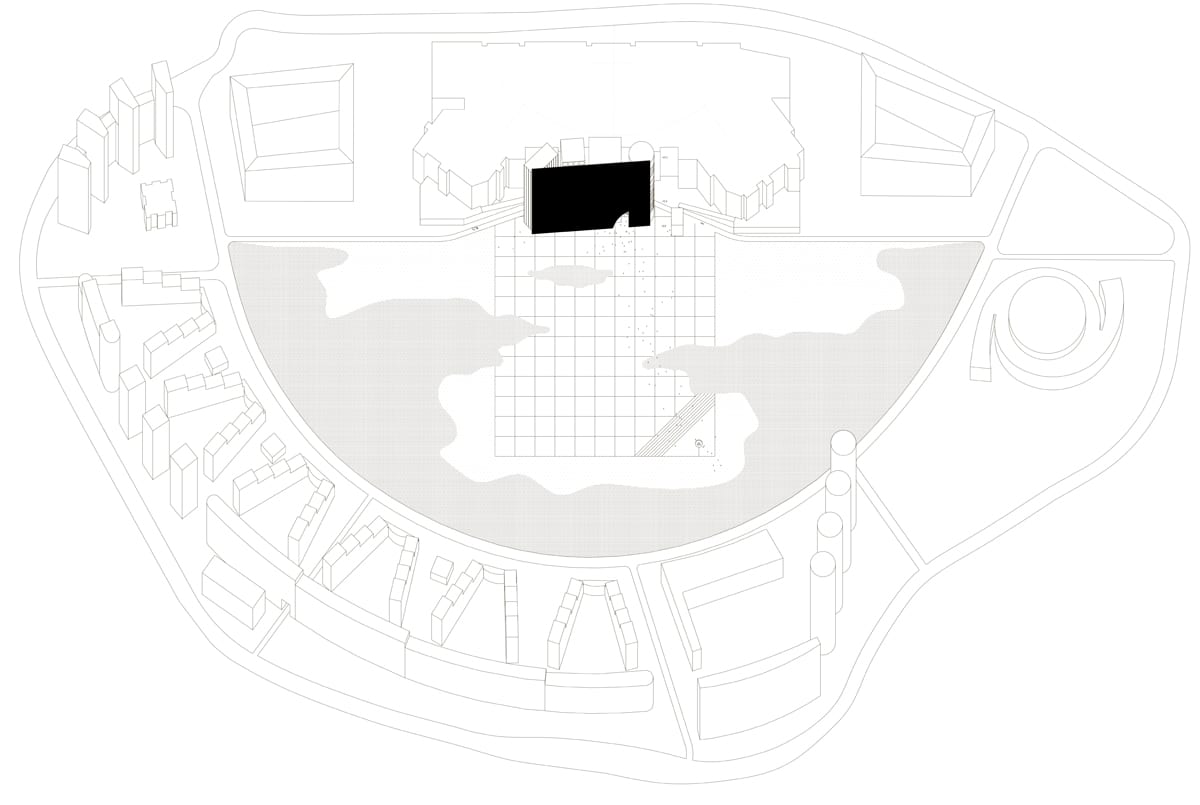

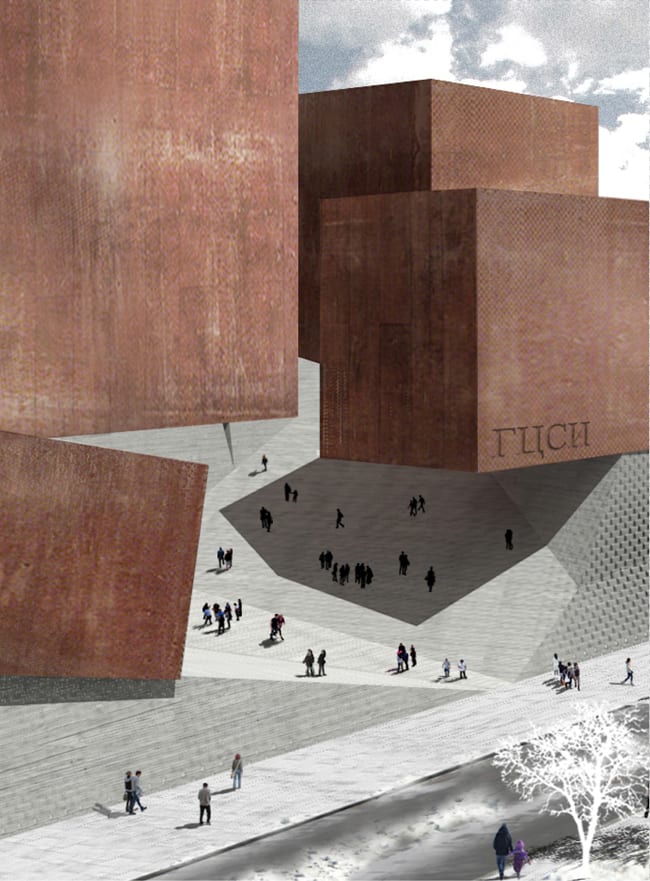

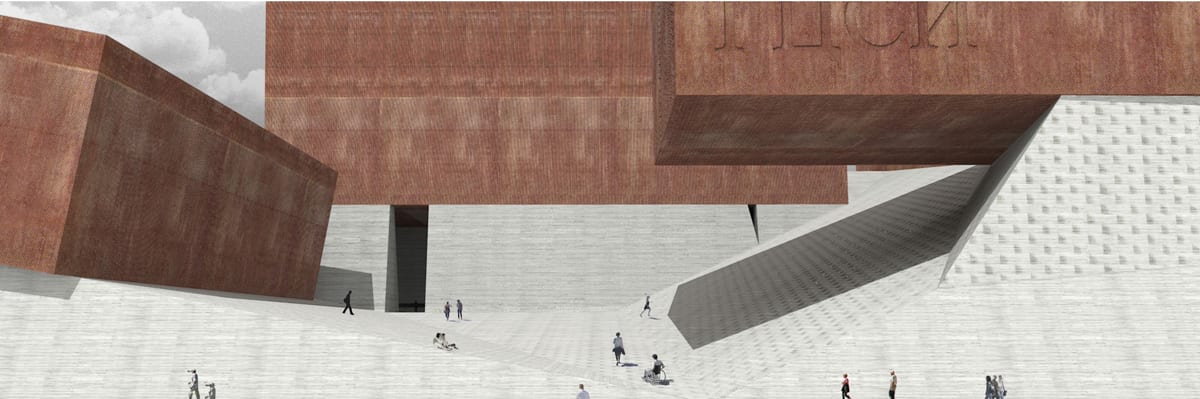

Second Place – MEL (Russia)

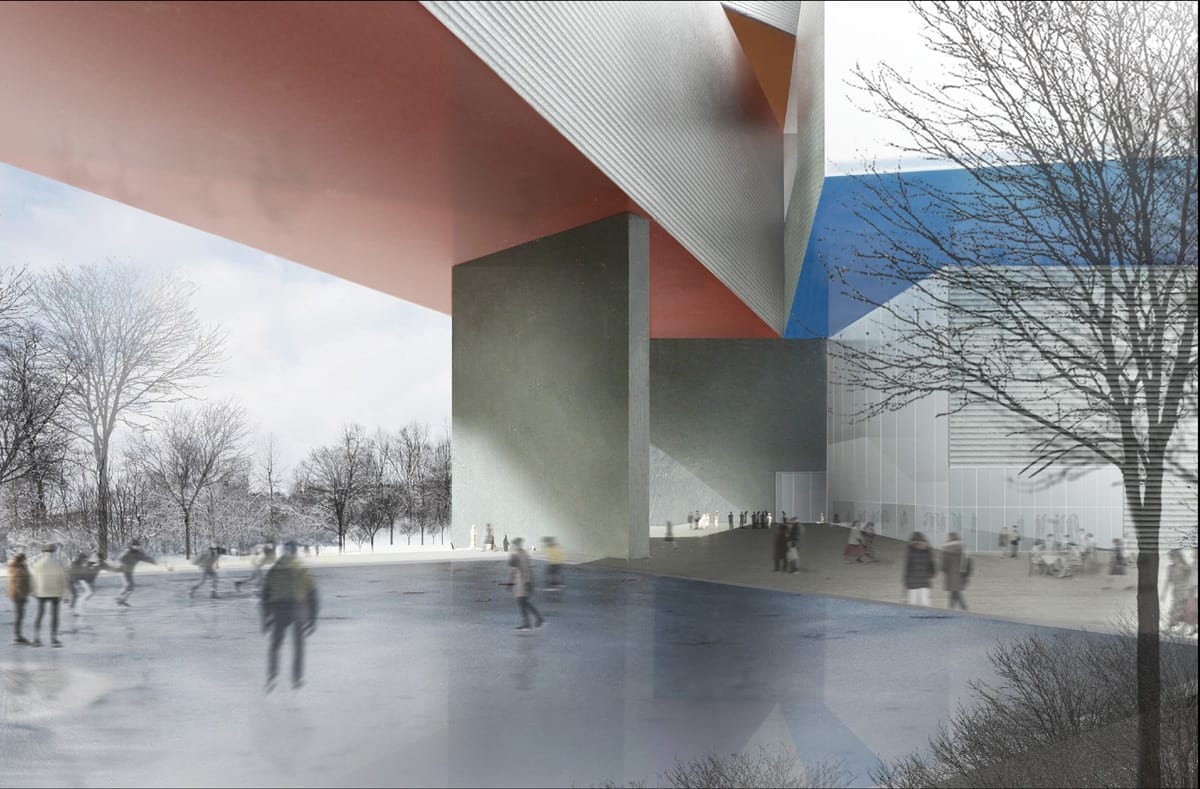

Melorama (MEL) suggested a raised platform functioning also as an elevated park to accommodate a number of pavilions housing the different permanent and temporary exhibits. This concept recalls Richard Meier’s Getty Museum, perched on a park-like setting in Los Angeles, and also featuring a number of separate pavilions. The intention is to allow visitors to go from one exhibit to the next, using the elevated park as the connecting element. There is only one problem here—one which Los Angeles does not have—and that is the weather. Although Muscovites are used to cold weather, moving from one location to another in January could present a problem. In this instance, the horizontality of the plan manages to somewhat obscure the shopping center to the rear—a potential plus, depending on how stark the façade of the shopping center turns out to be (It was still under construction at this writing.)

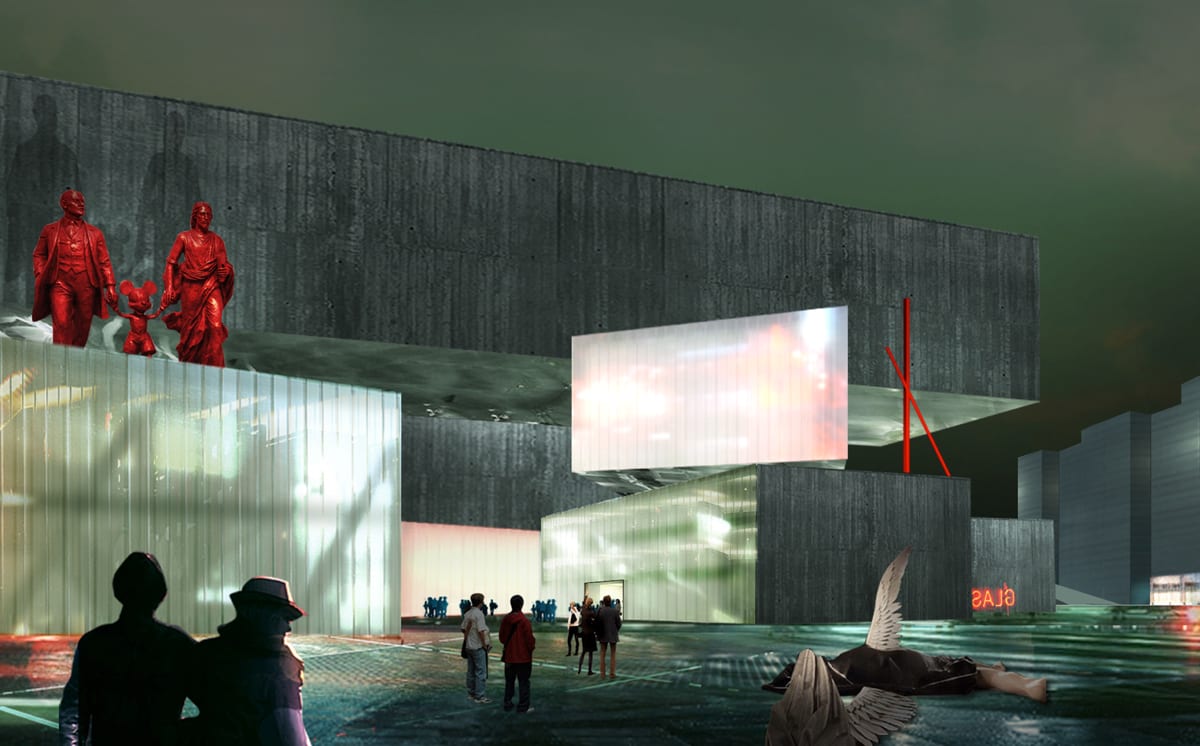

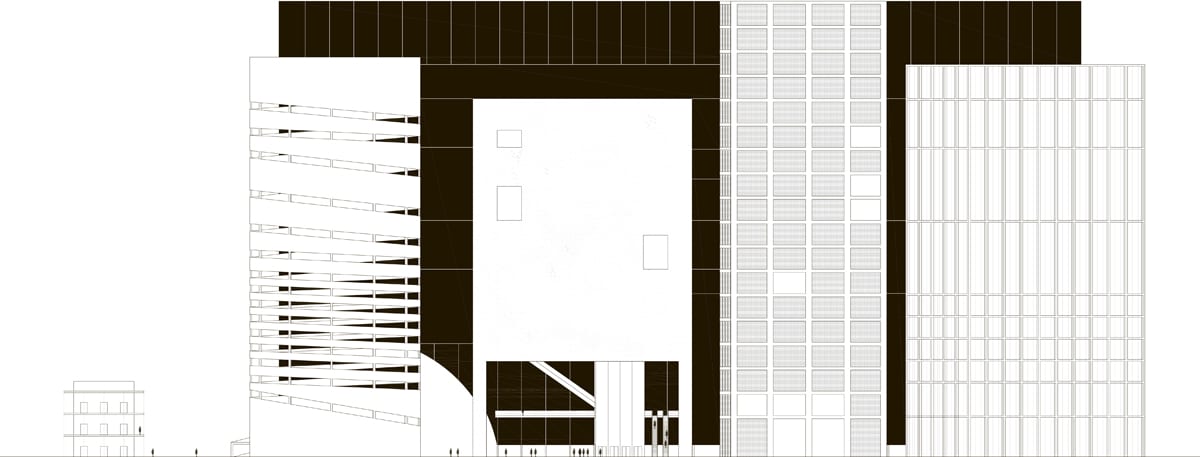

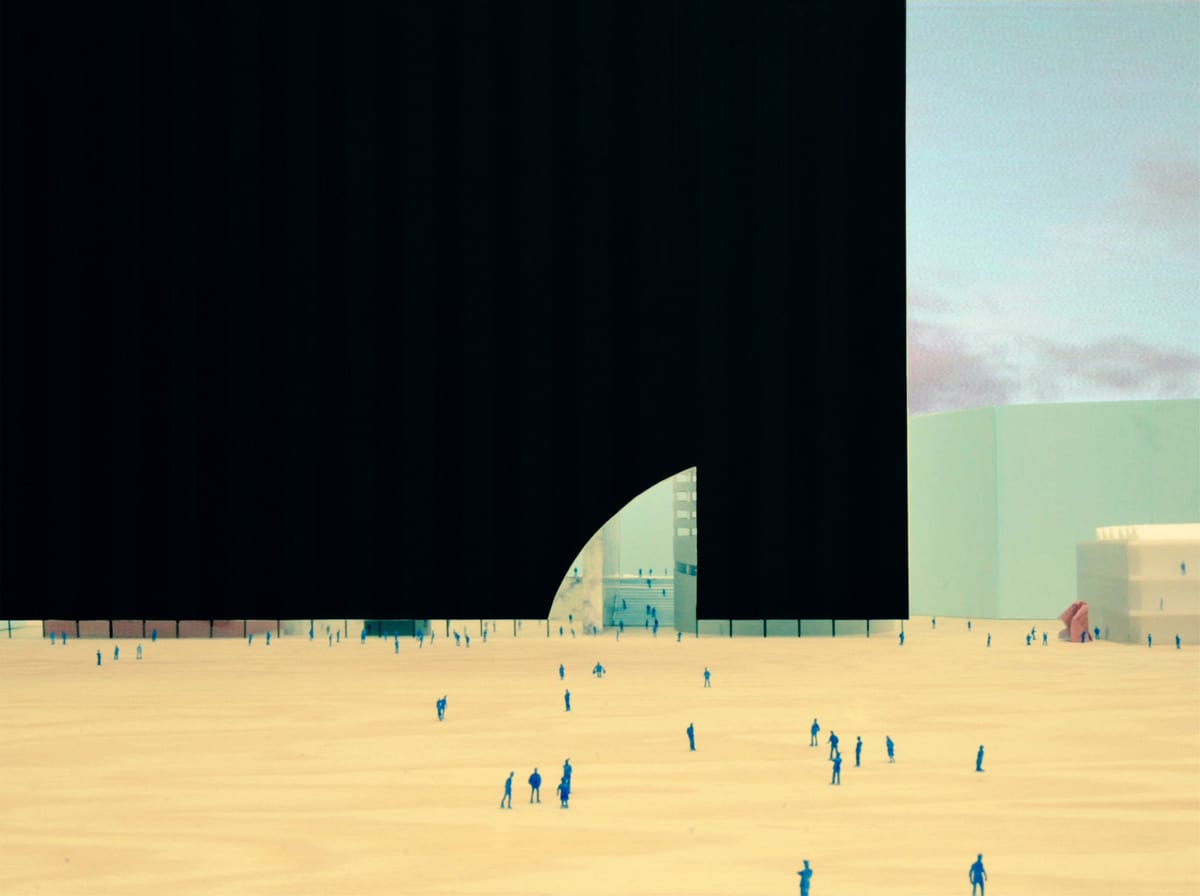

Third Place – Nieto Sobejano Arquitectos (Spain)

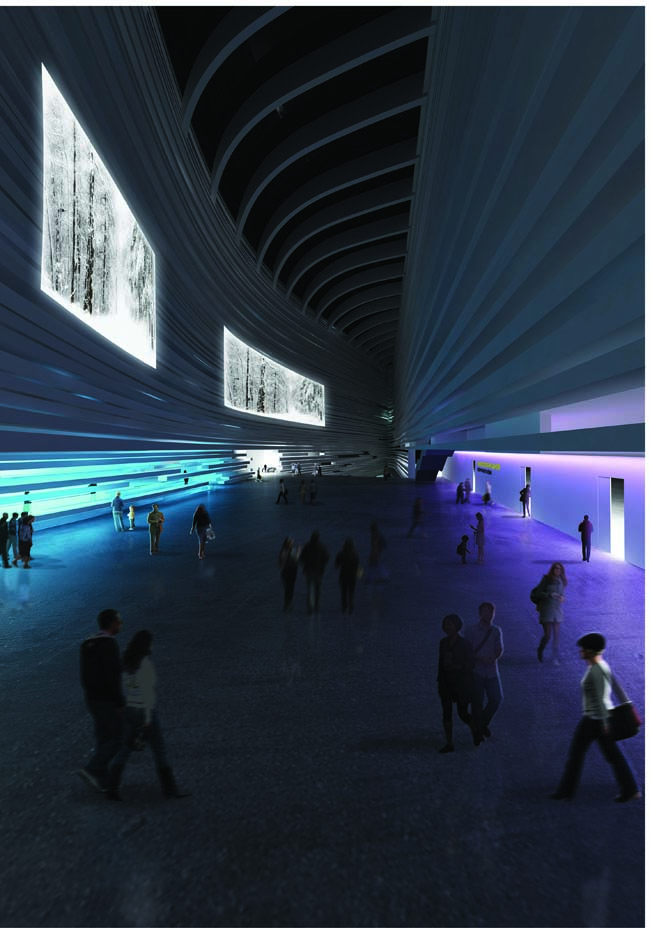

This was another variation on a theme: the authors suggested a series of cylindrical forms on a platform, whereby the structures are the result of permutations of these “cultural silos.” Again, there is no central focal point, but it is more like raising a curtain on a performance stage. Here, an elevated public foyer is the connecting link between the separate pavilions. The organization of the spaces is described thusly: “The artist’s workshops and residences are located on the upper floors of the last silo, which also incorporates the parking. The largest volume, situated by the major public entrance, houses the main auditorium. Conceived as a “Black Box”, this versatile platform offers a dramatic setting for theatrical performances, conferences, films, and unique audiovisual exhibitions. The striking façade panels facing the park enable media installations that have been specifically conceived for this purpose and context.”

Finalist – WAI Architecture Think Tank (China)

Finalist – Ghirardelli Giancarlo Architect (Italy)

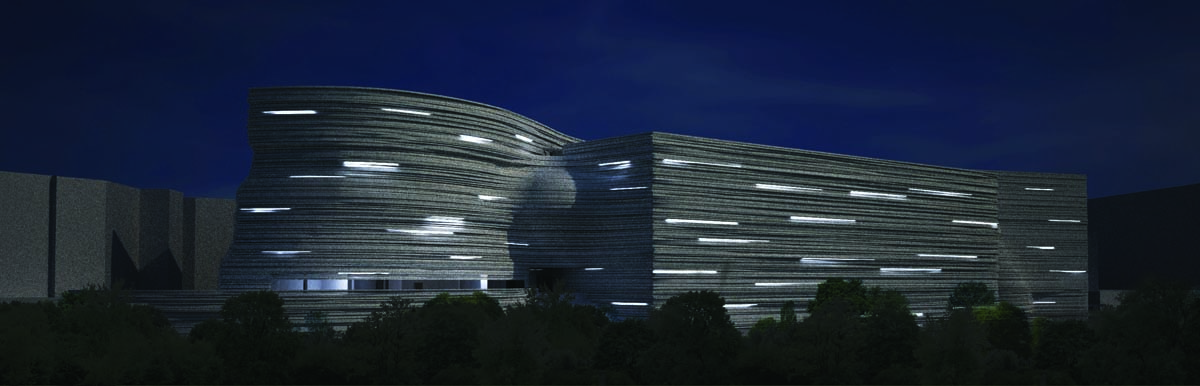

Finalist – Steven Holl Architects (USA)

Finalist – 51N4E (Belgium)

Finalist – Alejandro Aravena (Chile)