by William Morgan

2017 will mark one hundred years of Finland’s independence from Russia. It says much about the culture of this small but vibrant Nordic country that its official centennial project is not a trade center, a conventional hall, an arena, or a war memorial, but a library. Even better, this most architecturally astute nation has chosen the designers of this new library from an international open competition.

This is not so surprising considering the newly independent but resource poor Finland believed that education and literacy–hence libraries–were key to nation building. Architecture, too, has always played a major role in establishing the Finnish sense of identity; particular styles were employed as psychological weapons against Russian dominance in the years leading up to the revolution. Not long after the break from the Tsars, Alvar Aalto’s Viipuri Library announced Finland’s embrace of Modernism.

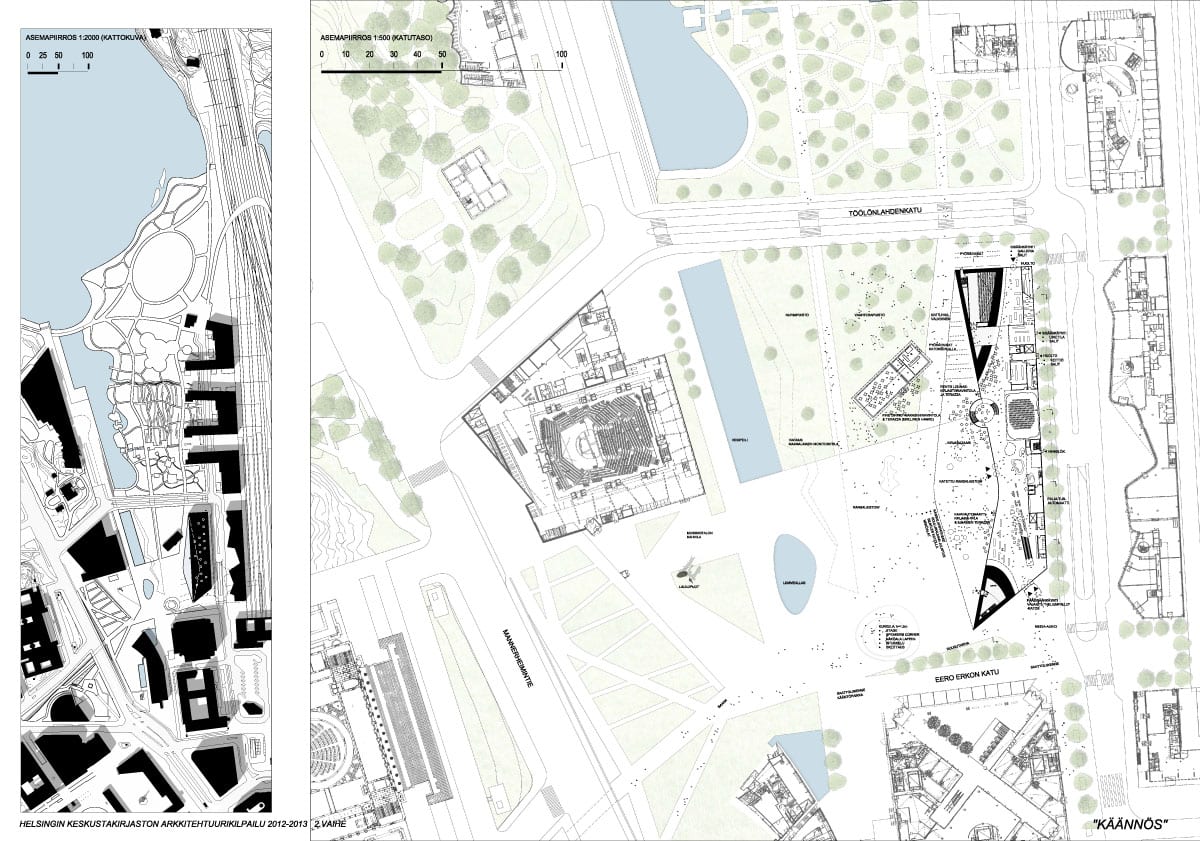

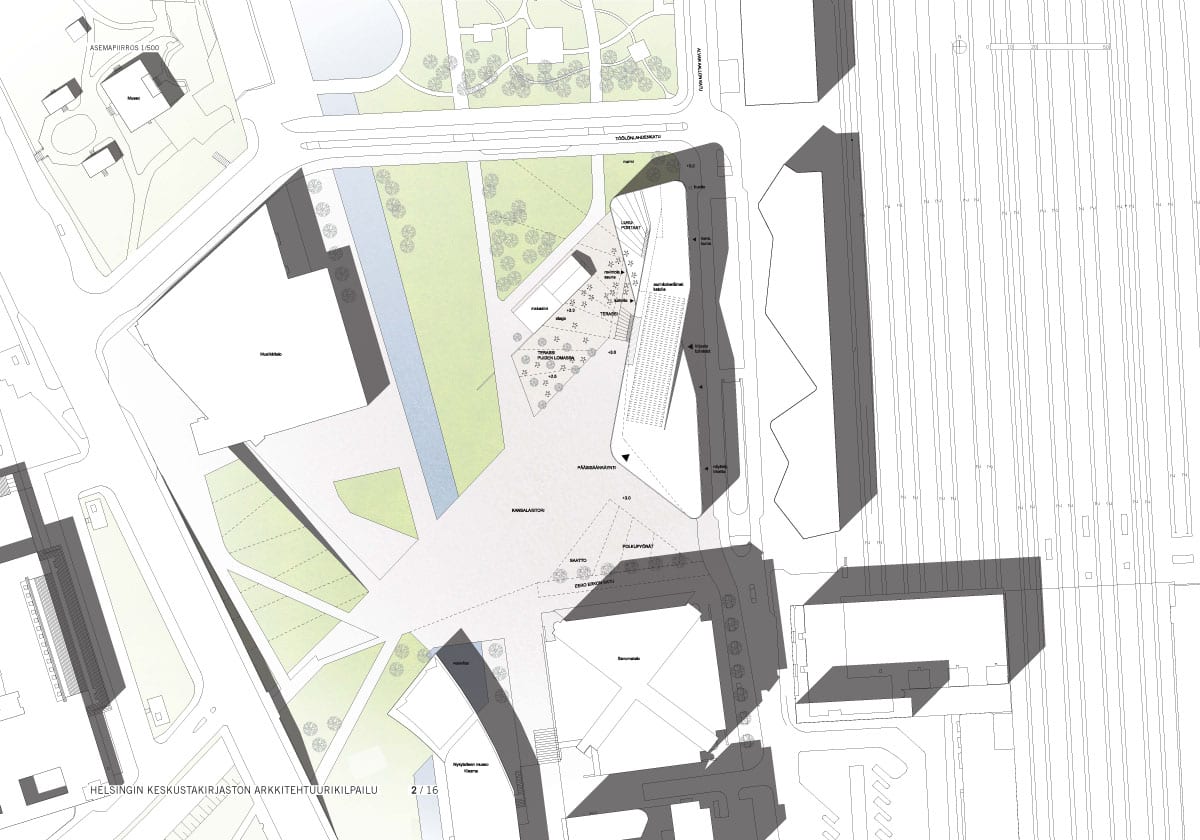

Libraries have played a role in Finnish society in the 20th century akin to that of the church in earlier times. Today, libraries throughout the country act as full-service community centers. So it is to be expected that the new City of Helsinki Library was envisioned as a major building of architectural and political importance. Its visible location is in the heart of Finland’s capital–opposite Parliament, next to Steven Holl’s Contemporary Art Museum, close to Eliel Saarinen’s iconic railroad station and Aalto’s Finlandia Hall.

All public buildings in Finland are designed by competitions and the Helsinki Library is no exception. The Finns, thus, do competitions well, and everyone from the struggling student hoping for the big break or the established master like Aalto has to be tested by the crucible of the competition. Ever since the competition for the contemporary art museum was controversially opened to a handful of non-Finns and won by Holl, foreigners have been slowly contributing wider choices. (The recent competition for the Serlachius Museum in Männtä attracted 579 entrants from 41 counties, and was won by MX_SI Architectural Studio from Barcelona.) In the case of the Helsinki library contest, there were 544 entries, although the jury report does not list either the names or the countries of origin for any of the entries that did not win a prize or an honorable mention. But one can assume that many Finnish firms would have entered, and the rest would be European, with a smattering from the rest of the world (two of the honorable mentions were awarded to Americans). But as the Helsinki modernist Mikko Heikkinen noted, “Superstars hardly ever enter competitions. They don’t need to, they have better things to do.”

The open, two-stage competition, in Finnish and English, was sponsored by the City of Helsinki. The 25,000 to 50,000-Euro prizes were probably less of a draw than the chance to build in such a prominent location in the heart of a city known for its architectural excellence. Entering teams had to have an expert in technology and had to have “experience of implementing the design of at least one pubic building larger than 5000 square meter during the last ten years.” The boilerplate design challenge asked for a “high quality and long-lasting solution, which fits into the cityscape,” as well as being “ecologically efficient and technologically and economically feasible” (it probably sounded less clichéd in Finnish).

The ten-person jury, chaired by the deputy mayor, included the library director, municipal department heads (real estate and planning), and a representative of the Minister of Education and Culture. The Finnish Association of Architects was represented by Vesa Oiva, designer of the new University of Helsinki library, and the distinguished modern designer Käpy Paavilainen. Kjetil Thorsen, the director of the Norwegian firm of Snøhetta was an “international expert.” In Finnish democratic style, the public was asked to review the five final schemes and to vote on them; a website, as well as touch screens around the city, were set up to facilitate the voting. The jury’s eventual unanimous jury winner polled second behind the “Diagonal Agora,” the Spanish entry in the citizen referendum.

That four of the six finalists were Finns is not surprising. Finns indubitably made up a large chunk of the entrants, plus it can be argued that native contenders had an advantage in their knowledge of climate and zeitgeist. One prominent Helsinki architect close to the competition noted that many of the entrants did not seem to understand the customs of the Finnish library as an institution, and “perhaps the Finnish competitors had a bit of an advantage in having thorough knowledge and experience of the system that is central to their education and everyday life.” He also suggested that knowledge of the site was essential, and this thus at the outset “created a difference between local and foreign offices.”

More notable is that this competition reflects the erasing of the decades-old fault line in Finnish architecture between rationalism and the organic–the Functionalism advocated by Aulis Blomstedt and exemplified by the “international Style” of early Aalto versus the freer forms of late Aalto and especially Reima and Raili Pietilä (themselves authors of a great library at Tampere). Only a dozen of the Stage I entrants marked for commentary submitted what could be called Miesian glass boxes. There were a number that could be perceived as tributes to the idea of Aalto, and even one Corbusian library that was part Villa Savoye, part Chandigargh. One design, called “Papersheets,” was a glass box wrapped with wavy sunshades to look like a giant book. Rather, the competition reflected current European trends: there was a lot of wood, not much color, and abundant scrim wall treatments; there were lots of “blob and fold” and few straight lines. Herzog & de Meuron seemed to be the architects most imitated. Mecanoo’s Birmingham Library had some progeny, too.

Those 30 designs that conceivably had a chance were called Upper Class, while the others were grouped into the kindly named Middle Class, and the unfortunately labeled Lower Class. Since no one except the finalists were identified, the jury criticism is often blunt. The goal was simply to find the best solution for what the City of Helsinki calls a “150-year solution.” Two Americans received Honorable Mention, Monica de Leon and a small firm from Charlottesville, Virginia called Kutonotuk.

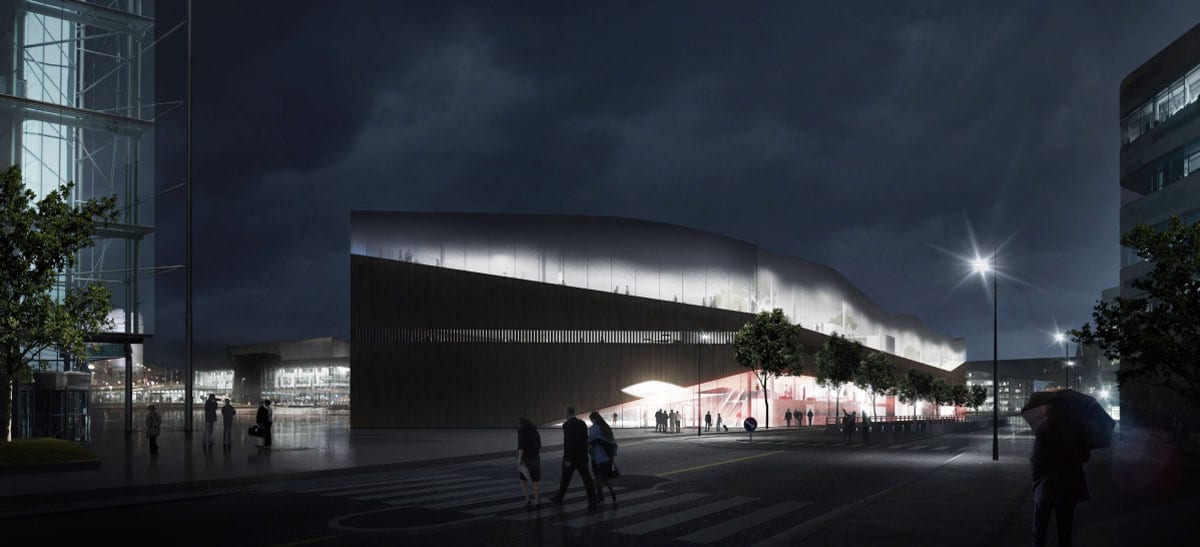

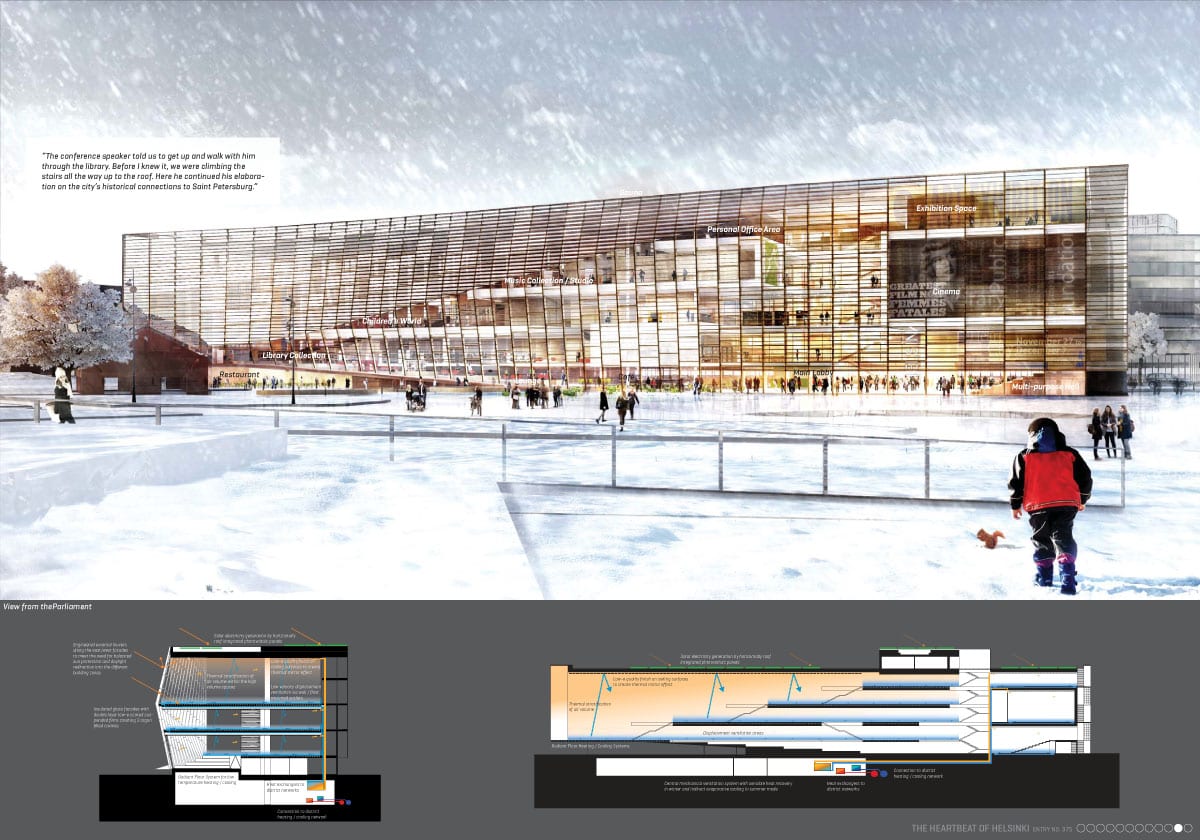

The late Henning Larsen (who once worked for Jørn Utzon, speaking of memorable competition winners) reached Stage 2 and was thus a finalist, but garnering an honorable mention with “Heartbeat of Helsinki.” The Larsen design features a long undulating façade formed by handsome wooden screens that the architect poetically called lamellas. Except for losing out on the cash prize, the Dane’s design was a notable contender.

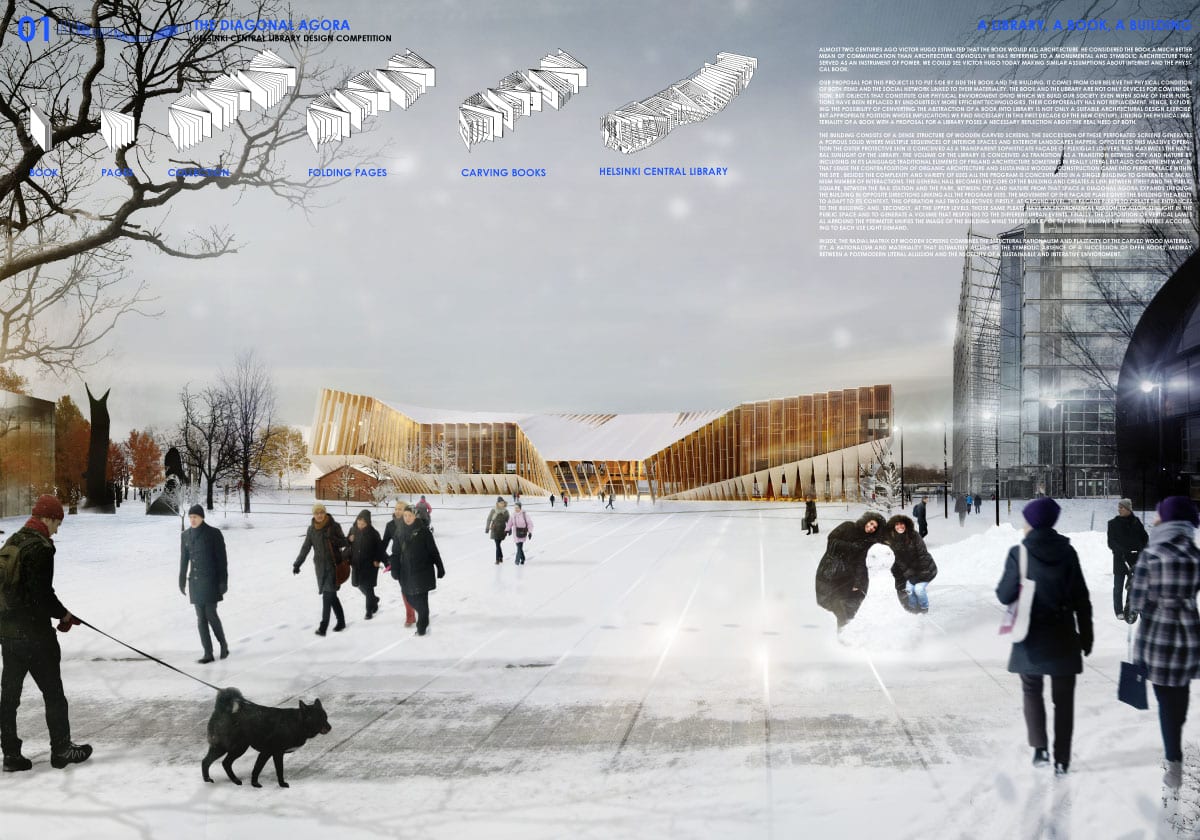

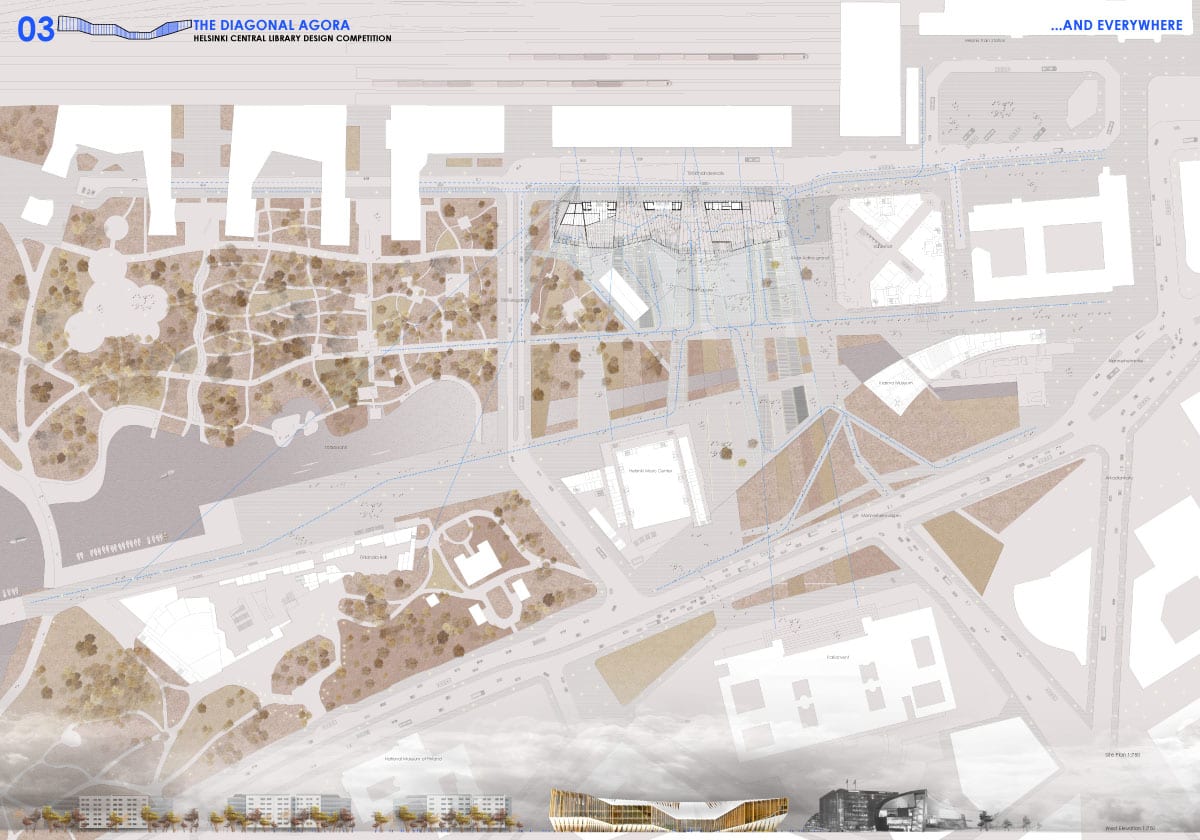

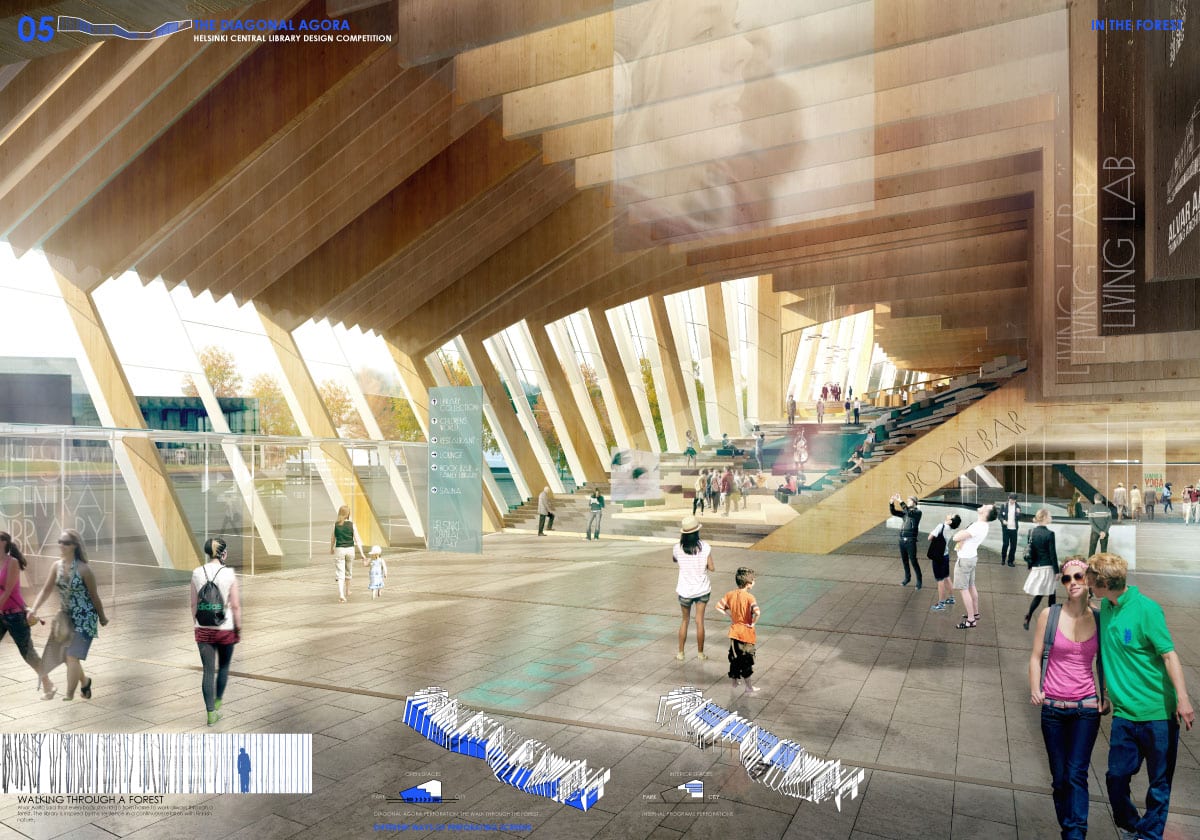

The other non-Finnish entry among the finalists, a group of six young Spaniards who banded together to do this competition, produced the intriguing design that won the public poll. “Diagonal Agora” is an undulating accordion of a building, with the result that roof construction would have been unnecessarily complex. Also, the jury was disappointed in the changes made from Stage 1; they found the new design to be more agitated with a challenging structural system (it does seem the most tortured of the seriously considered projects). But the interior earned high marks for impressive spatial planning. It seems to be a lively design whose rounded shapes would have been perhaps a little too close (in proximity) to Steven Holl’s “Kiasma” next door.

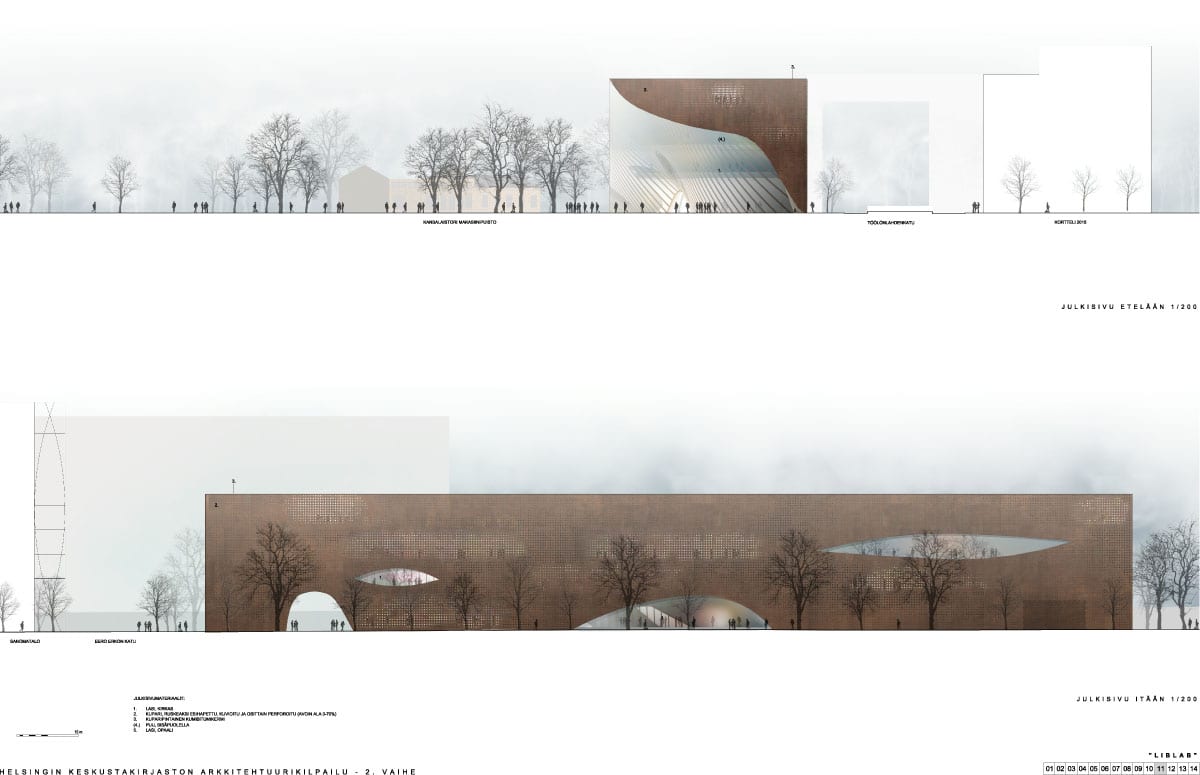

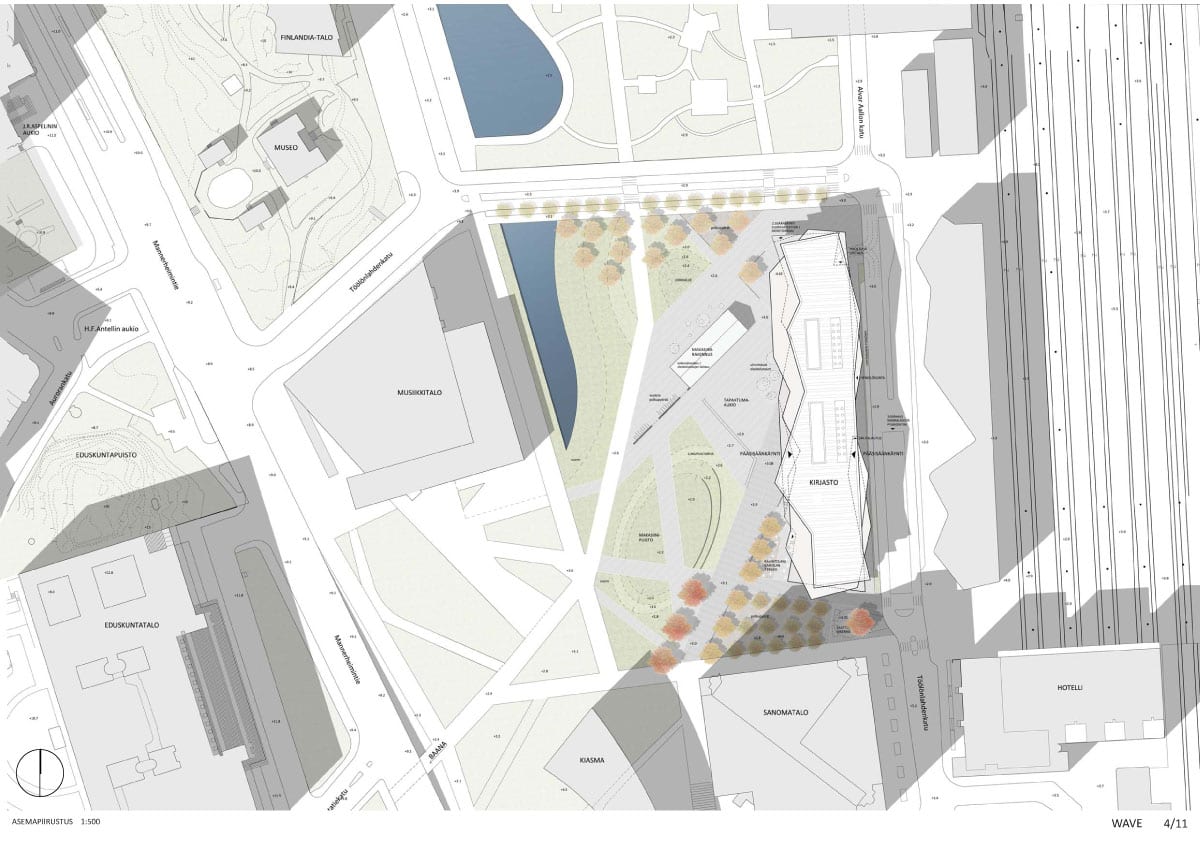

“Wave” (or actually “Wave/1,” as there were other waves–Aalto means wave in Finnish) is the work of Huttunen-Lipasti-Pakkanen, a young Helsinki firm that has garnered a lot of press for houses, churches, and commercial work. The scheme relies upon a series of stacked boxes “with considerable amount of glass surfaces” that could have made indoor climate control problematic. Here again, the jury felt that changes effected after Stage 1 made this design–hitherto “modest, restrained, and rather enclosed”–one in which “composure has been decreased,” with a resultant “disintegration of the totality.” Changing Stage 1 wood to metal (and one that is treated to prevent patinization) “created a harsher look for the building.” Preliminary stage jury comments seem to have created some counterproductive angst within the design teams, as “Wave/1” “is a unique and exceptional proposal, where the further development, however, did not completely fulfill expectations.”

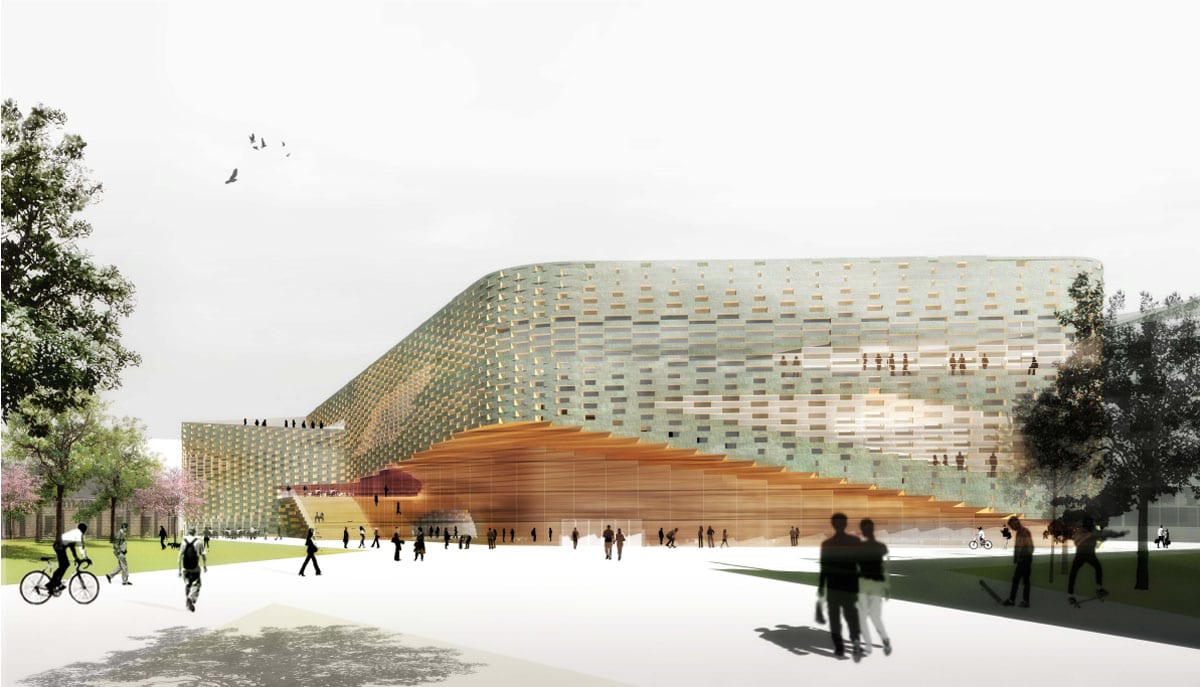

Instead of awarding second and third place prizes, two projects were paired at third place. “Kasi,” by the Helsinki firm of VERSTAS Architects (who won another open international competition to expand Aalto University in Espoo), earned favor from the jury for its changes from Stage 1. The sensuous infinity symbol plan is the most stretched–and the most Zaha-like, yet it is contained within a wood scrim. The jury cites “Kasi” for being “inviting and easy to approach,” and “spatially confident and informally stylish.” The projecting entrance is formed by curving layers of wood that may be an homage to Aalto’s Finnish Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair of 1939, but it is dramatic regardless of its lineage. There is a handsome combination of Expressionism and monumentality that would have made for a notable library.

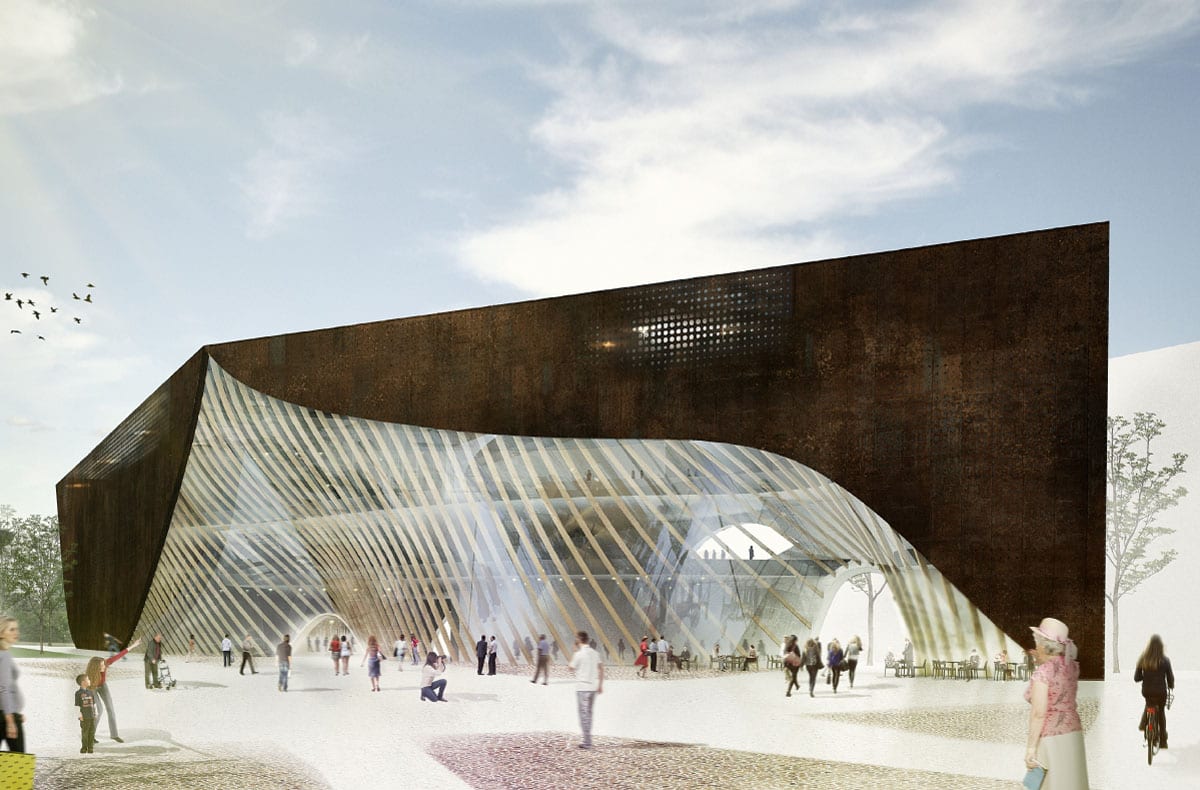

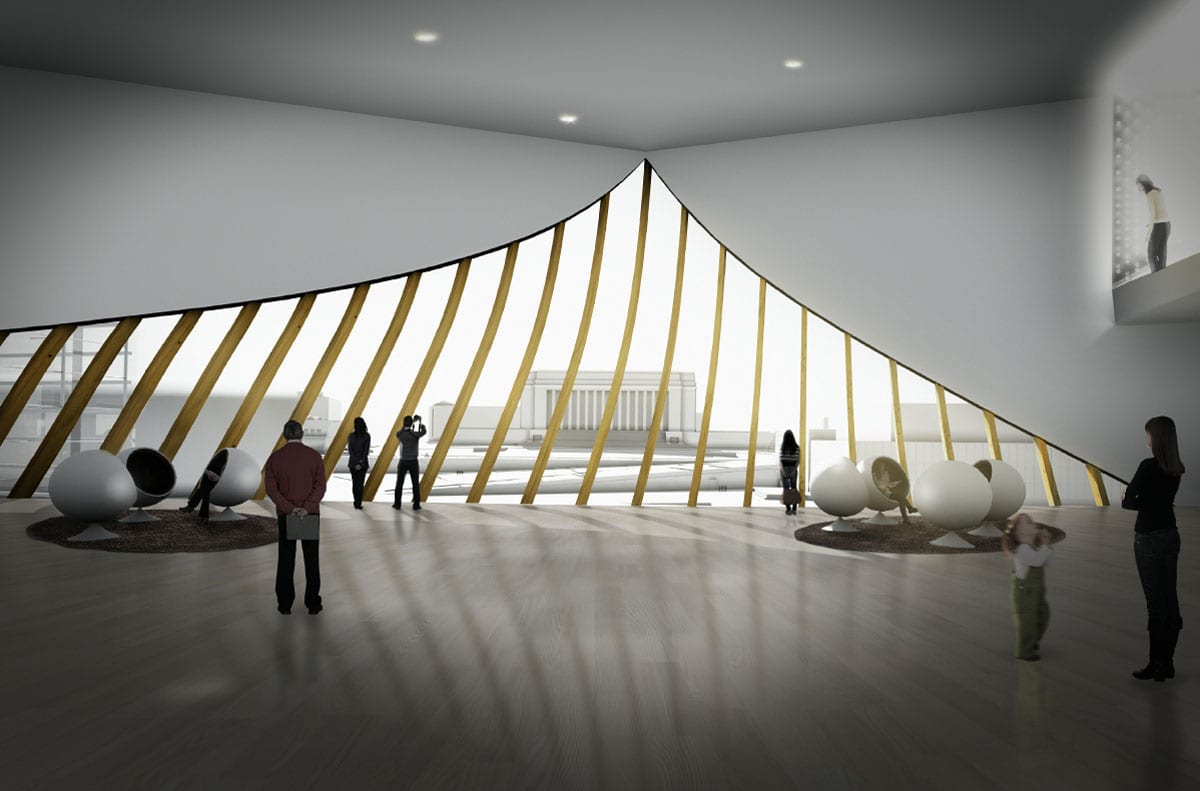

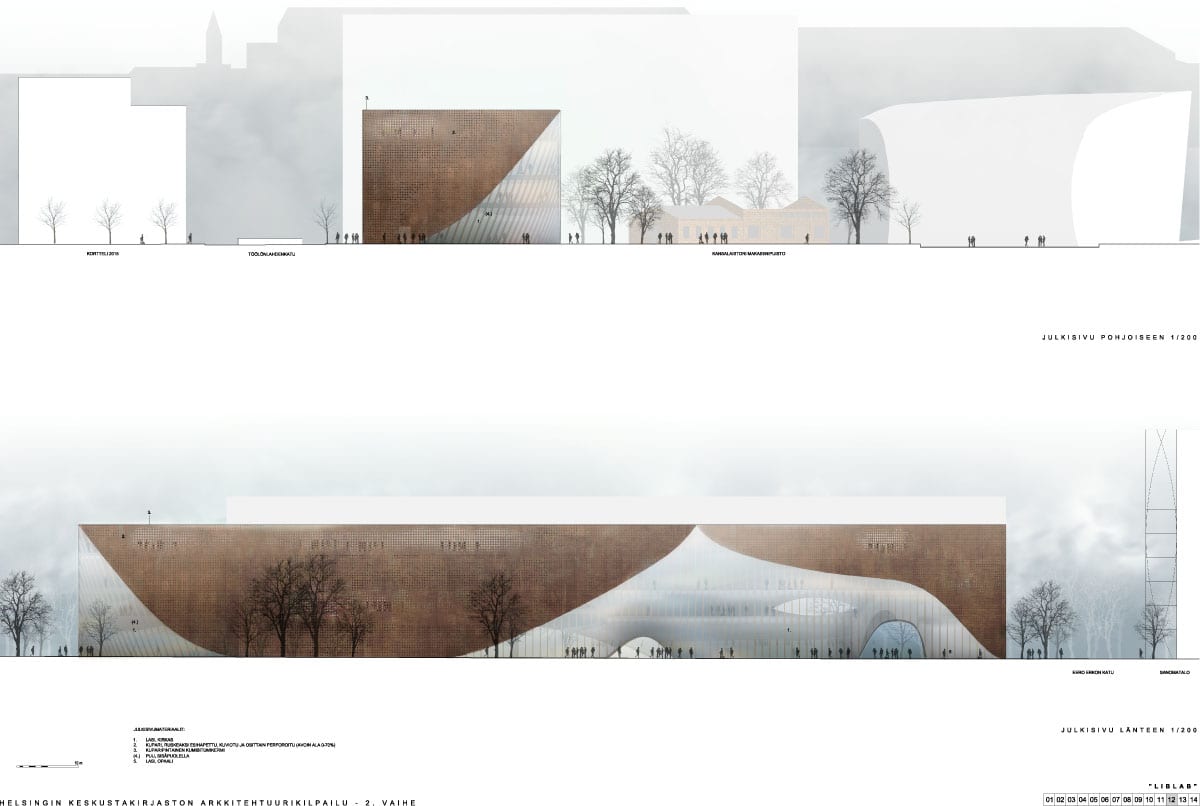

Another young Helsinki firm, Playa Architects, that does primarily domestic work and housing, shared the 3rd Prize with what may be the most fun–or outrageous–design. The plan and basic configuration of “Liblab” form a straightforward rectangular block. But the entire building is wrapped in a sculptural dark copper skin that contrasts with huge amounts of open glass. Some on the jury perceived the sharp corners where the edges met as “frightening and threatening.” This is yet another Stage 2 proposal that the jury liked better in its Stage 1 form. Still, the building received high marks for planning and its sense of monumentality. The patinated and perforated brown copper surface that forms the opaque organic bits is reminiscent of the heavy eaves at Le Corbusier’s Ronchamp. With the wooden structural beams behind the glass acting a skeleton, the building’s main opening suggests the baleen of a whale. Of all the final designs, this is the most joyous, the one that would have been the most iconic, and the one that would most easily have garnered a nickname while giving Helsinki a new symbol. Chandigargh meets Moby Dick.

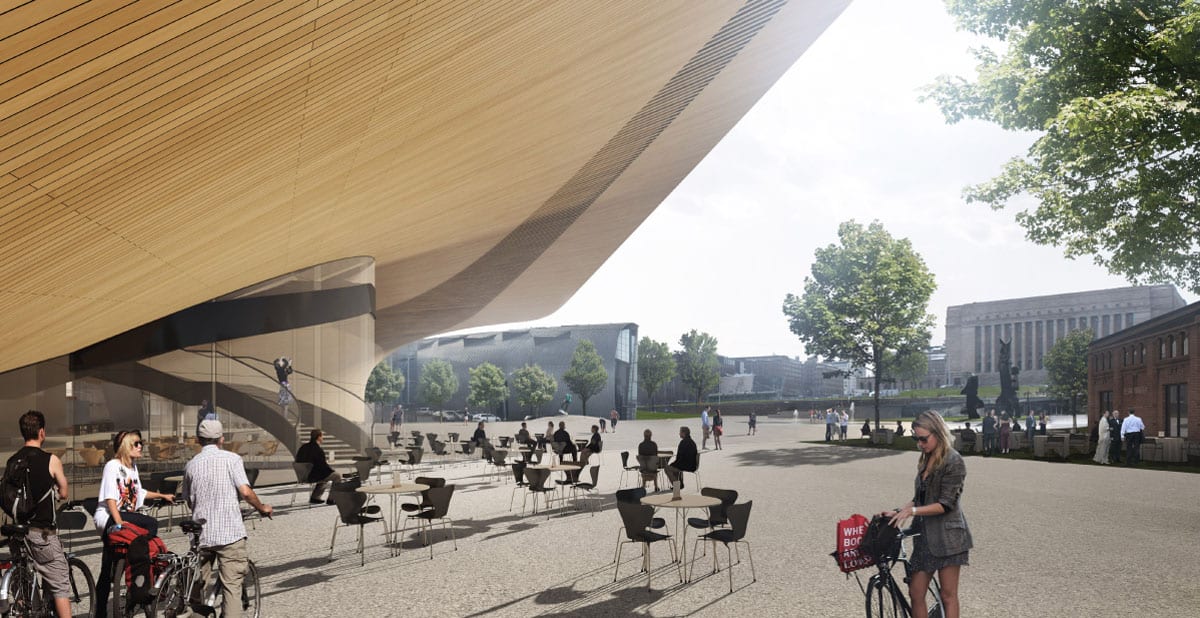

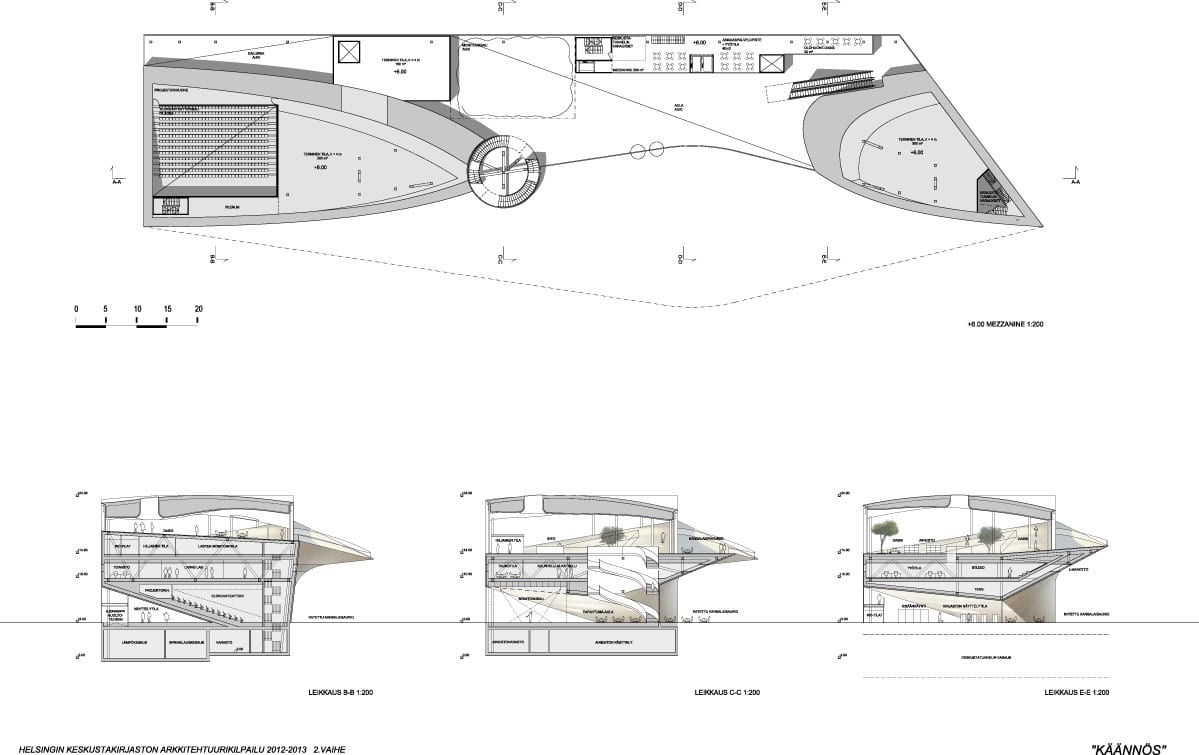

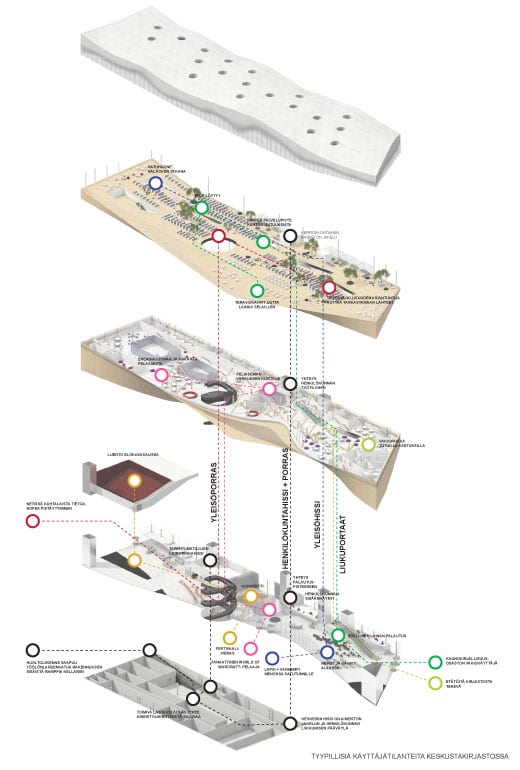

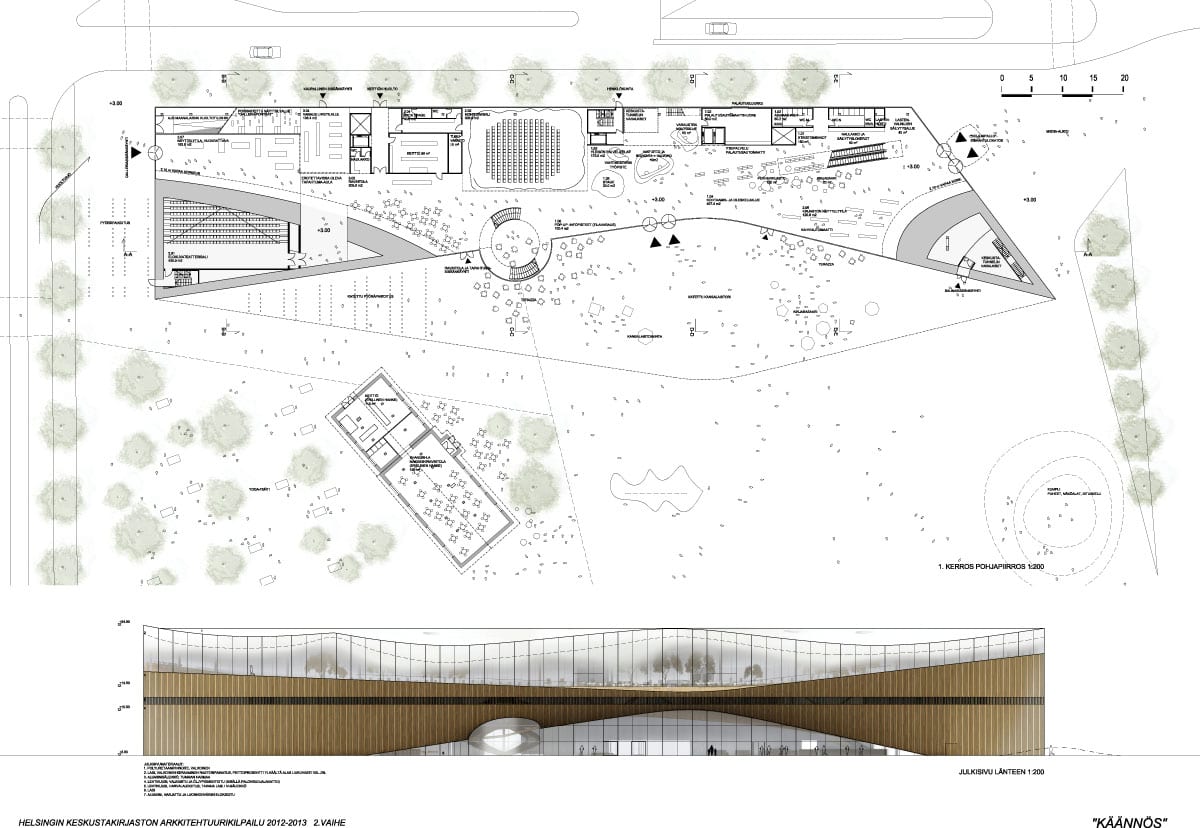

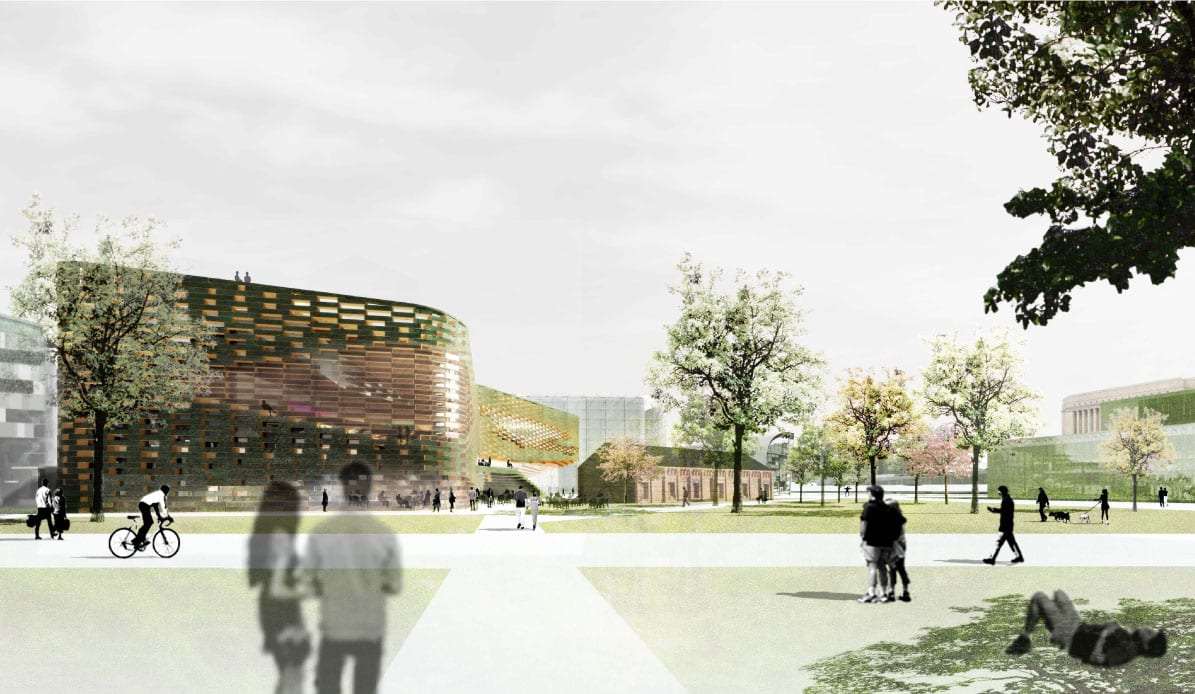

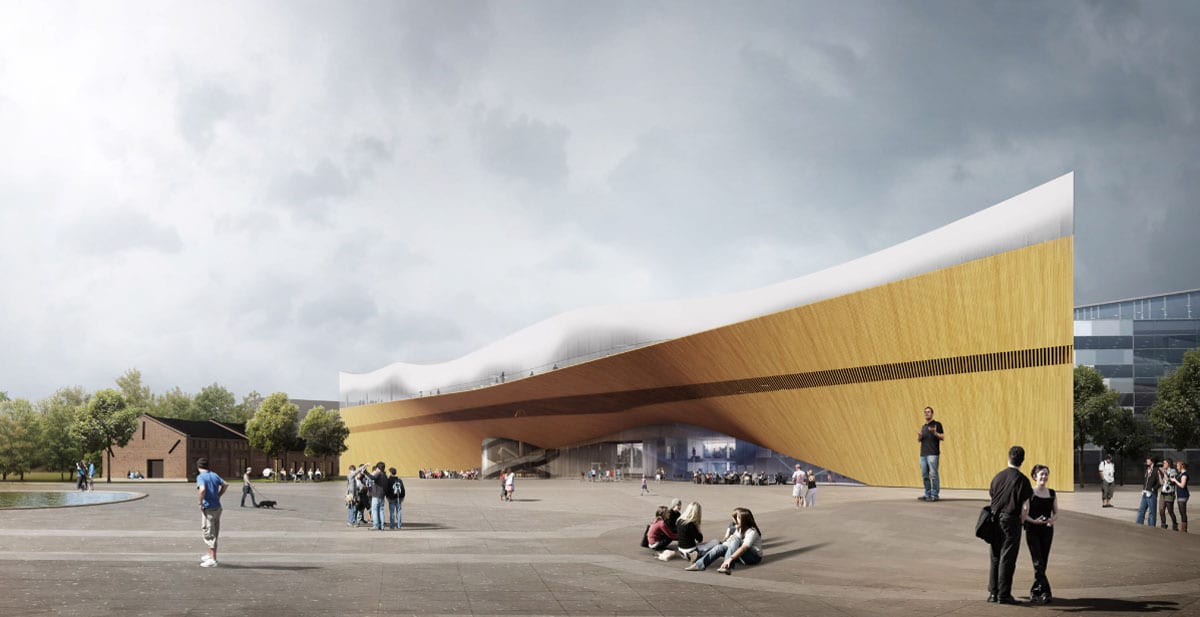

“Käännös” by ALA

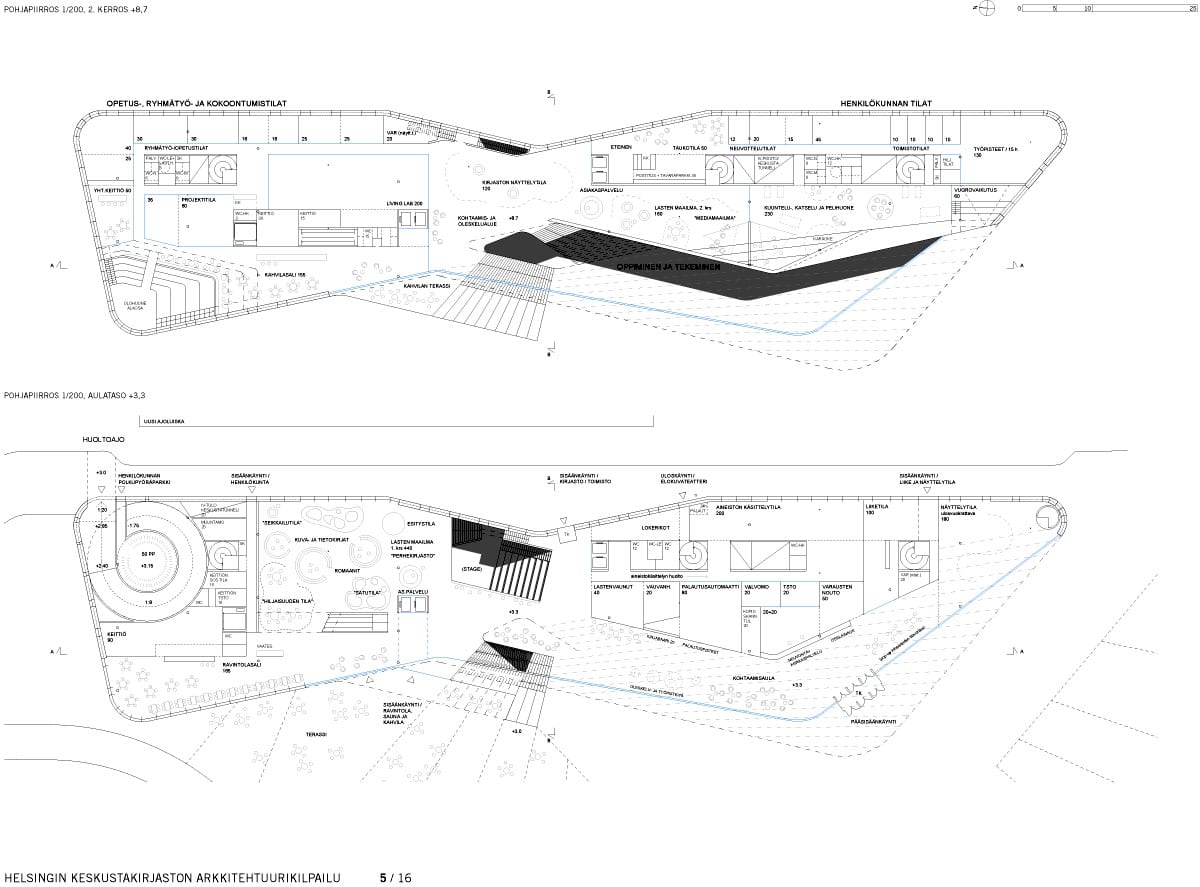

“Käännös” by ALAThe winning scheme, Käännös, is made of wood (a bleached Siberian larch) and it also has the requisite wiggly bits. Although two sides of the buildings are straight lines, the front corners fold under to create a central entrance, plus a wavy translucent roof looks like clouds (inspired by Herzog & de Meuron’s Elbe Theatre in Hamburg, according to some critics). The winners are yet another Helsinki firm, ALA, fifth place winners in the Aalto University contest and the renovators of the Pietiläs’ Finnish Embassy in India. ALA earned high marks for being the only Stage 1 firm that markedly improved its project for Stage 2 (“the overall concept is increasingly clearer”). Combining both the organic and the practical, “the building is inviting, easy to approach and identify with.” The peeled back ground floor allows the entrance to become part of the public square around the library, linking the building to the park and making it seem more accessible.

Inside Käännös, the parti relies on an old fashioned idea of a grand stairway which reaches to what the jury cites as the “workshop-like character” of the second floor, with its diverse functions of activities, meeting rooms, “citizen’s balcony,” and even a public sauna. The top floor, with its magnificent views of the city, heavenly firmament roof, and quiet reading room aspect will be a wonderful sanctuary within the center of the capital.

Although not as much fun as “Liblab,” the ALA scheme has the merits of solid planning, sustainability, and a healthy mix of Finnish history and psyche, as well as enough monumentality and novelty to make for a terrific addition to this remarkable city. Despite the understandable domination of Finnish designers, this contest achieved what it set out to do. As Antti Noujöki of ALA said, “Our initial question has been: can we create a public space which is relevant and rewarding in the digital age.” With “Käännös” Helsinki ought to have the symbolic library it seeks.

Winning Entry: “Käännös” by ALA (Helsinki)