by John Bentley Mays

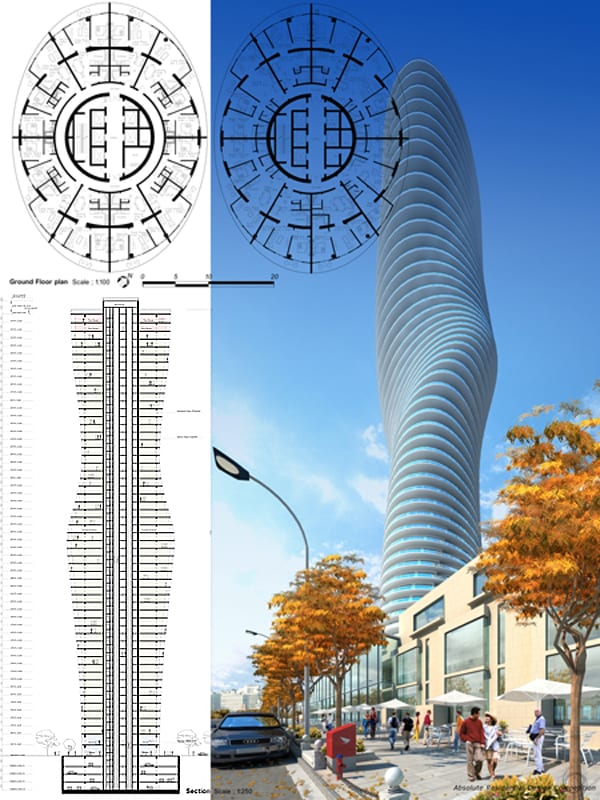

Completed towers (photo ©TomArban)

From Hans Scharoun’s Romeo and Julia high-rises in Stuttgart to the World Trade Towers in New York, the interplay between two high-rises has always provided a fascinating challenge for architects. Such an opportunity presented itself with The Absolute Towers competition in Mississauga, Ontario, announced in November, 2006, which drew ninety-two entries from around the world. Six entries were shortlisted for a second stage, and the winning design by a young Chinese firm, MAD was announced on March 28, 2007. The project was recently completed, and the following article by John Bentley Mays, which appeared in Canadian Architect (August 2013), recounts much of the circumstances surrounding the selection process by an international jury. -Ed

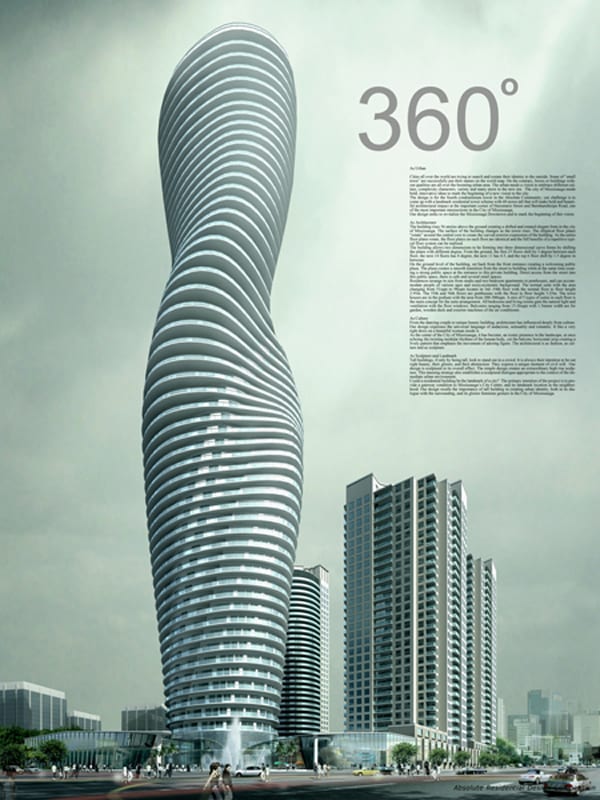

Six years ago, when Yansong Ma’s design for the first lyrically sculptural, curvaceous Absolute World condominium tower was unveiled, some critics predicted the project would never be built at its intended location, an important crossroads in the rapidly growing Toronto edge city of Mississauga—or anywhere else. According to the naysayers, the technical hurdles involved in raising a structure this unconventional in shape would prove insurmountable. Even if someone figured out a way to put it up, they argued, doing so would be unaffordable for the Toronto-area backers, Fernbrook Homes and Cityzen Development Group. It was further alleged that investors and prospective homeowners would never buy into a residential scheme so dramatically different from standard cereal-box apartment blocks.

“There were many doubting Thomases,” Cityzen’s president and CEO Sam Crignano told me recently. “Criticism came from my peers in the development community, and everyone had a reason why—cost reasons, structural reasons, marketing reasons, technical reasons. There was always an expert out there who had reasons why this could never happen.”

Other voices, however, quickly rose to the defence. Some media observers in Canada and abroad, for example, hailed Ma’s scheme as a breakout from the standard design template that had dominated the art of the residential high-rise in North America since the Second World War. Hazel McCallion, Mississauga’s popular, much-elected mayor, early on declared herself a supporter. And key players in the real-estate industry joined the pro-Ma chorus when the structural engineers recruited by the developers pronounced Ma’s striking plan doable for a reasonable price and within an acceptable time frame. Crignano estimates that executing the design cost him and his partners “around 20 percent” more than raising an ordinary condo stack. Profits were acceptable, however, due to the increased prices the project could command.

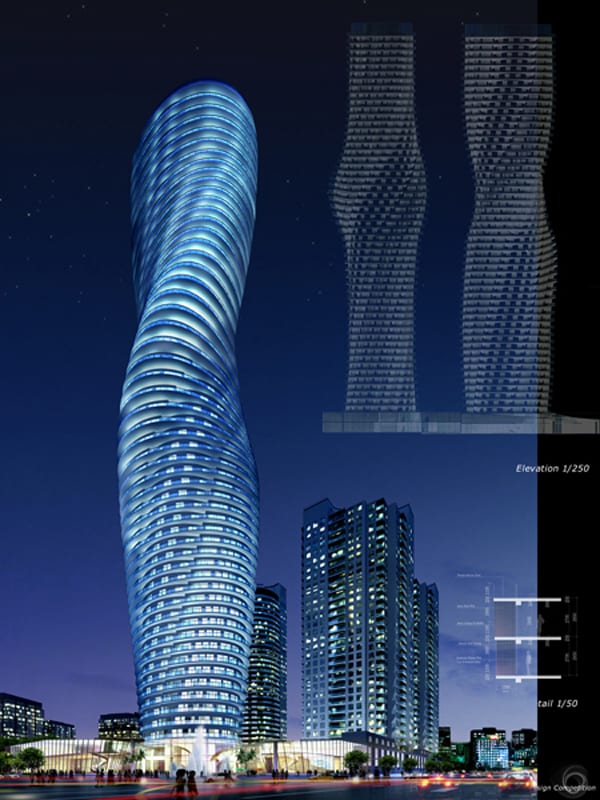

It was the condo scheme’s success in the marketplace that ultimately silenced the opponents. Investors and brokers finished snapping up the product only a couple of days after it appeared, even though the price of $450 per square foot was markedly above average (around $400) for Mississauga. Popular demand to own a suite in Marilyn Monroe—as pundits instantly nicknamed the building in homage to the pneumatic movie star it resembled—was in fact so fervent, the developers immediately put its young, Yale-trained and Beijing-based architect to work on a second adjacent high-rise. This one, like the first, sold out rapidly.

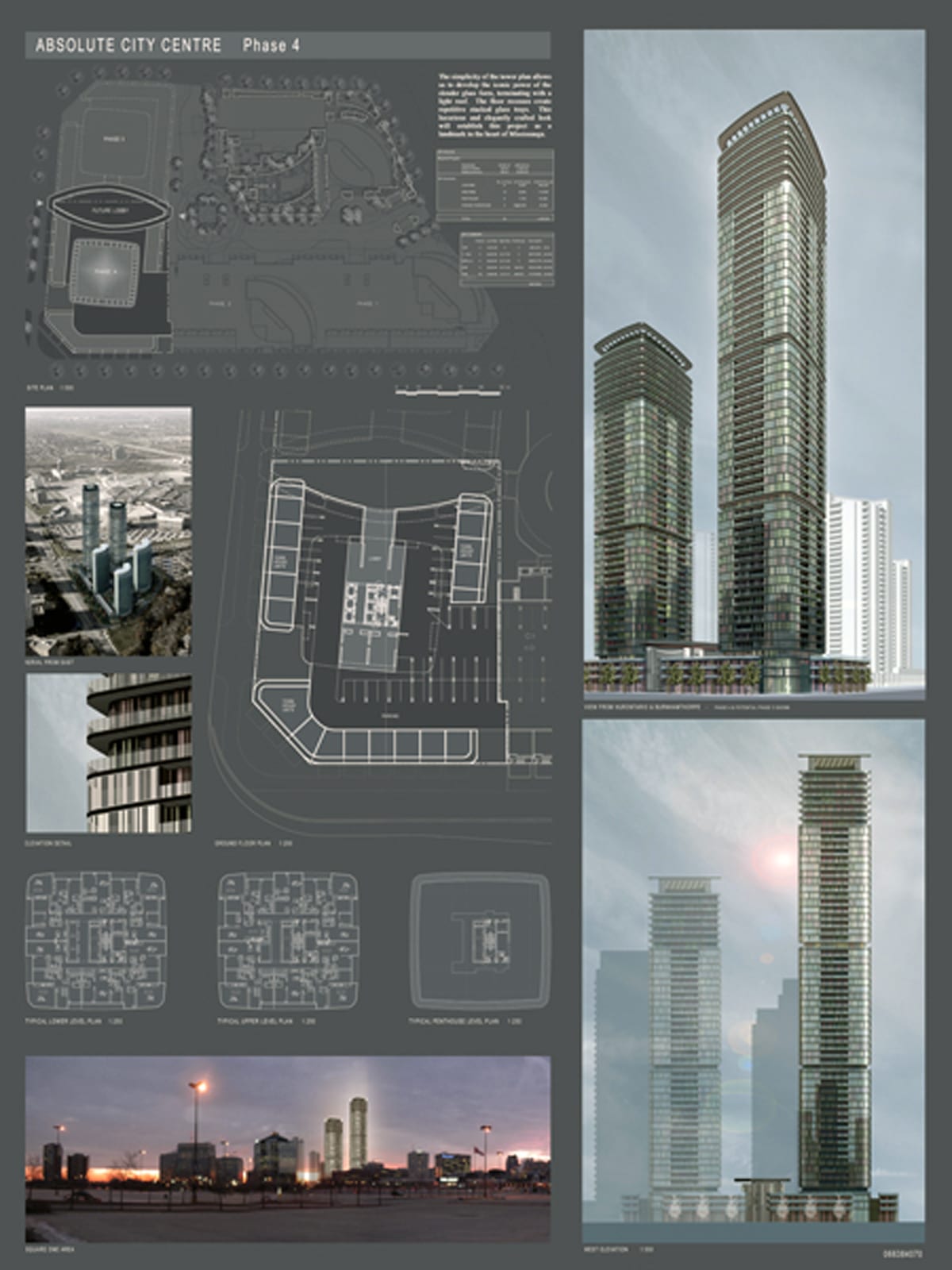

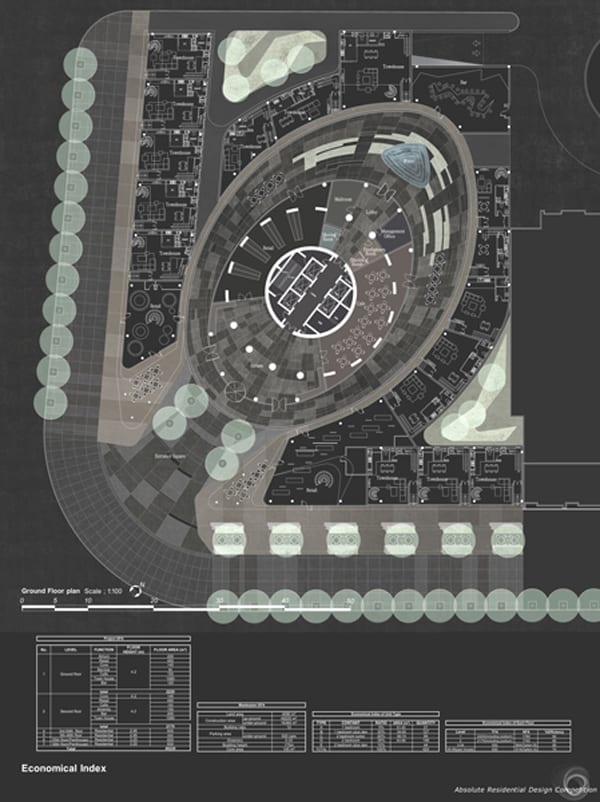

Last year, the spotlight fell again on Absolute World, when a jury of experts assembled by the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat—a widely respected non-profit research and advocacy group headquartered in Chicago—named Yansong Ma’s now-completed project the “Best Tall Building Americas” for 2012. With this award, the Absolute towers won the same admiring recognition from the design professionals that they had long enjoyed in the mass media. (For the record, the residential component of Absolute City Centre, as the entire master-planned development at the corner of Burnhamthorpe Road and Hurontario Street is known, consists of three shorter, conventional towers designed by the Toronto firm formerly called Burka Varacalli Architects, and the two structures by Ma, which are together called Absolute World. There are about 1,850 units in the entire complex.)

Now that both buildings are up and occupied and the cheering has largely subsided, it is surely time to ask what, if anything, these much-praised towers have contributed to the contemporary discussion about architectural practice, about cities, and especially about the role tall buildings should play in the intensification of the world’s largest metropolitan areas. Everyone knows the towers are unusual, and public opinion seems to agree that they are beautiful. But so what?

So this, for one thing: they have shown private-sector developers that design competitions for high-rise residential schemes, which are nearly unheard of, can—with good will and broad vision on the development side—effectively summon forth ideas that are both artistically exciting and commercially viable.

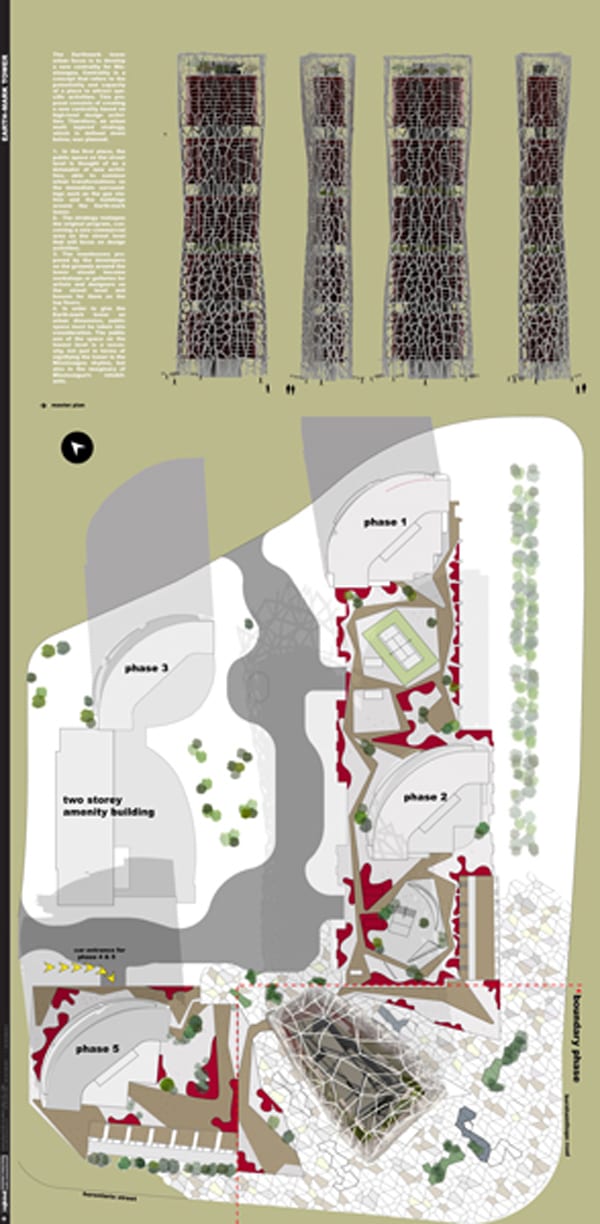

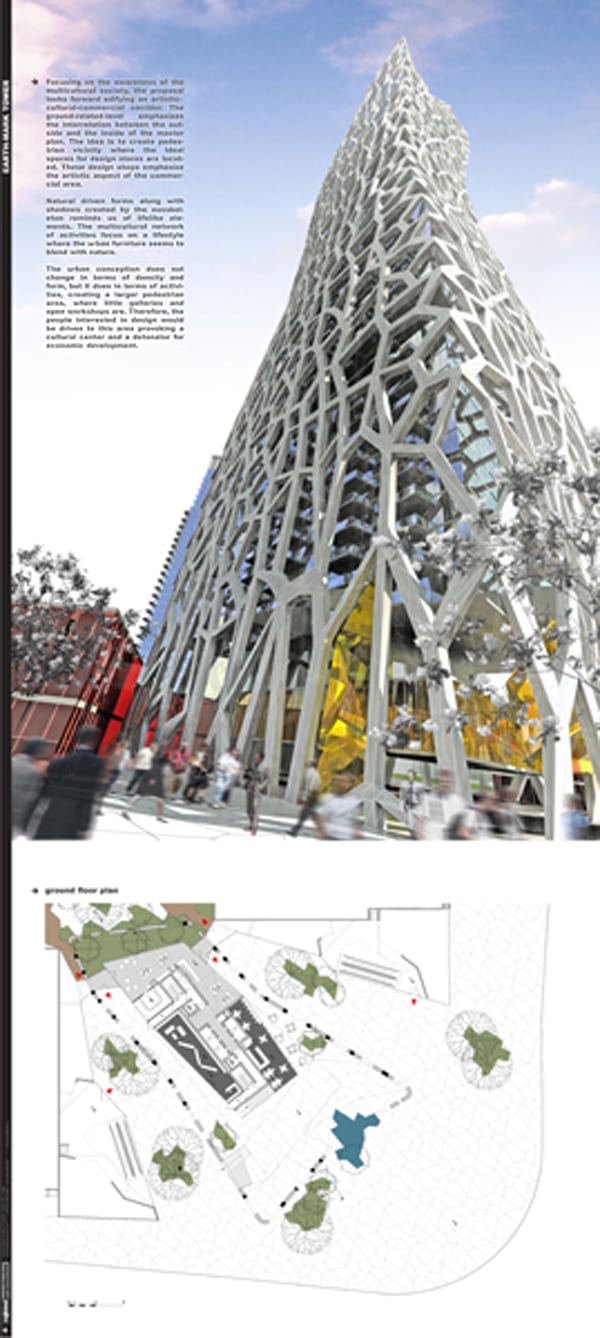

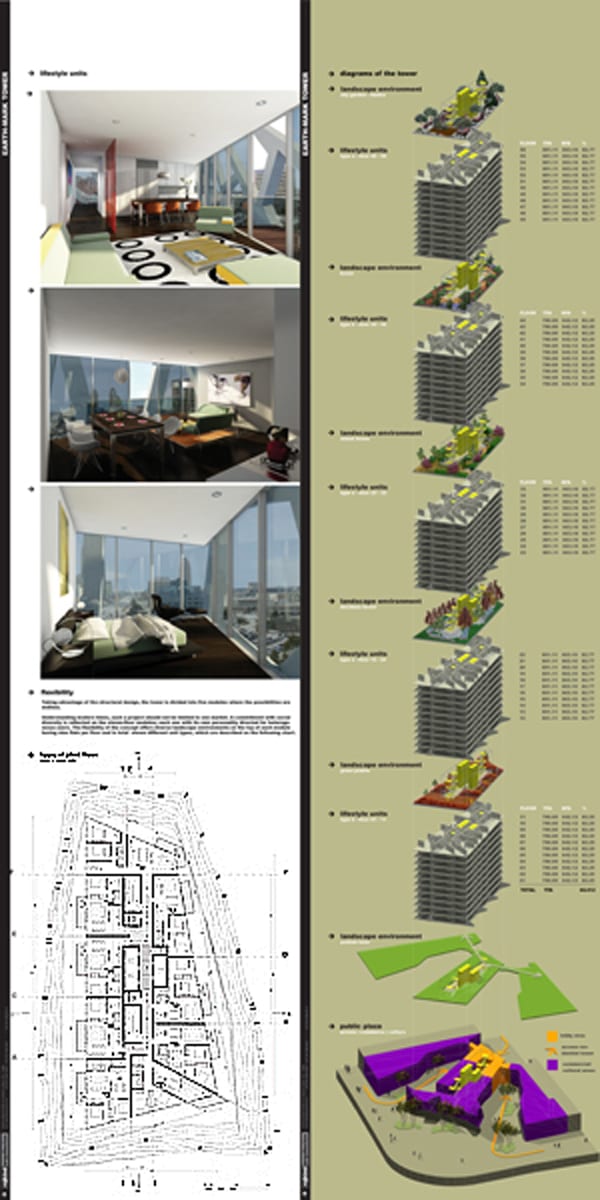

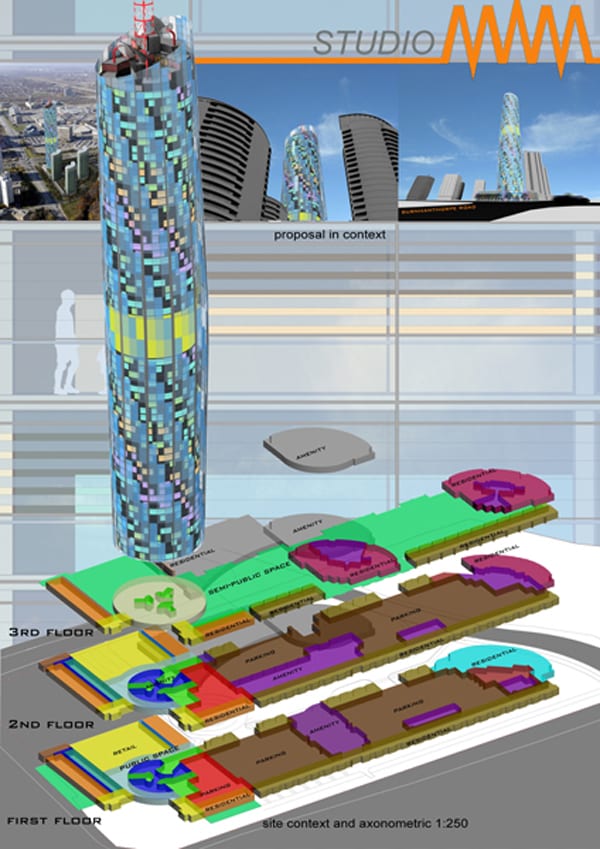

The call for proposals broadcast by Cityzen and Fernbrook (via a website) and the subsequent juried selection process were the work of people largely unknown in the great world beyond Toronto, but they had a well-defined, easily understandable objective: to set down a large, unignorable exclamation mark in the sprawling, very indifferent low-rise and mid-rise suburban landscape that rings Toronto. Because Mississauga’s zoning bylaws imposed no restrictions on height or density at that time, potential competitors were given wide licence to let their fancies roam; the developers’ brief only laid down the size and number of apartments that were expected. As it happened, the contest (launched in late 2006) attracted more than 600 expressions of interest from firms and individuals in 70 countries, and 92 actual submissions.

Why all this attention? “I think,” Crignano recalled, “it’s because of the novelty of a design competition for a residential condominium project, the fact that it was made available to anyone and everyone. It stimulated a lot of conversation and got a lot of people interested. It was highly unusual.”

As the public discovered when the six finalists were announced, in early 2007, the quantity of this keen interest did not translate into a uniformly high level of quality. The eight judges (picked from a mostly Canadian pool of developers, urban planners, architects and critics) had settled on a disappointing mixture of some advanced ideas (such as those put forward by Yansong Ma and Mexican designer Michel Rojkind) and entirely routine tower schemes.

That Ma’s plan won at all was perhaps due to the enthusiasm it generated among the developers. For their part, Crignano said, the business partners had made up their mind going in that whatever went up on the site they owned in central Mississauga “would have to be something that made a statement. From the first time I set my eyes on [Ma’s] design, I immediately took to it—so did the mayor. Visually it was so strong. It stood out among the others.”

In addition to proving that a competition can work even in a part of the real-estate industry where it’s uncommon, the completion of the towers, in much the same shape that Yansong Ma originally envisioned them, demonstrates that architectural design can be radical while simultaneously respectful of the laws of physics and economics.

Shortly after its selection, Ma’s plan was handed off to Toronto’s Burka Architects and structural engineers Sigmund Soudack & Associates. Under orders from Crignano and his partners not to tamper with the art of what Ma had done, the Canadian consultants set about turning the non-orthogonal, fluid scheme into something that could be built.

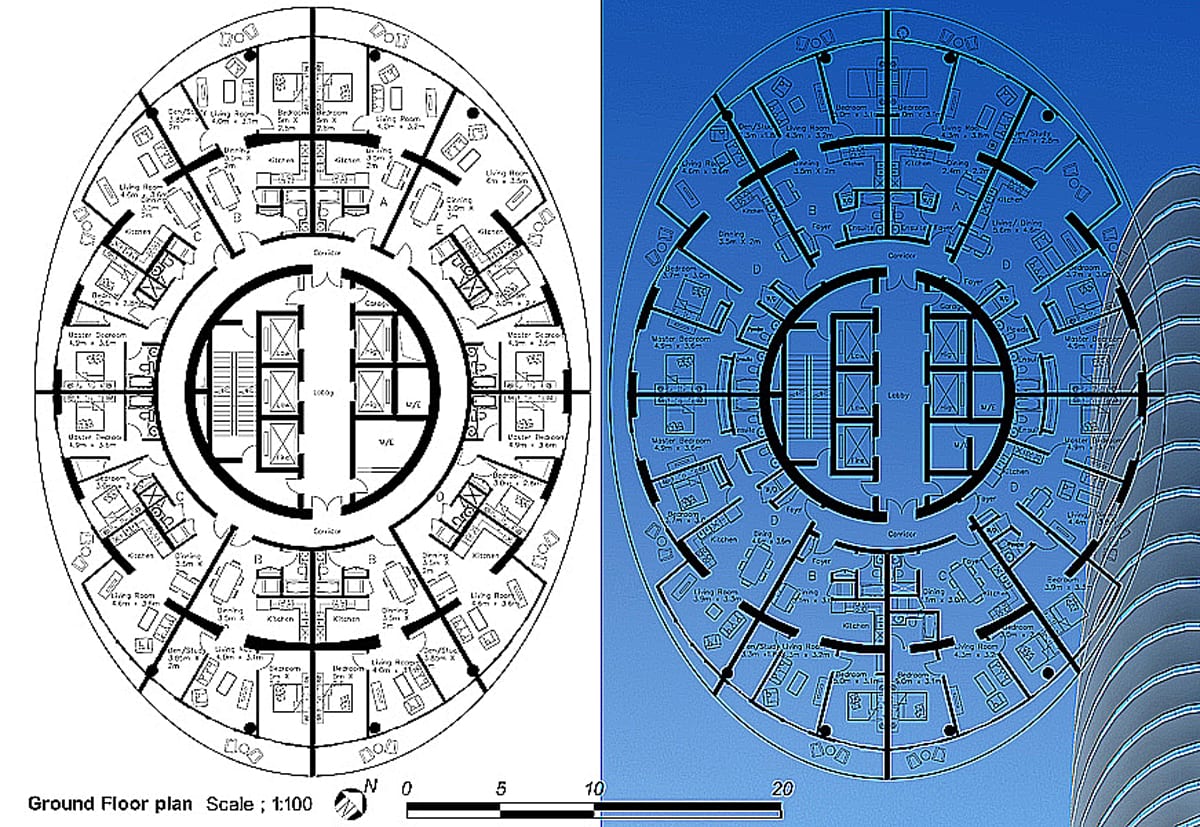

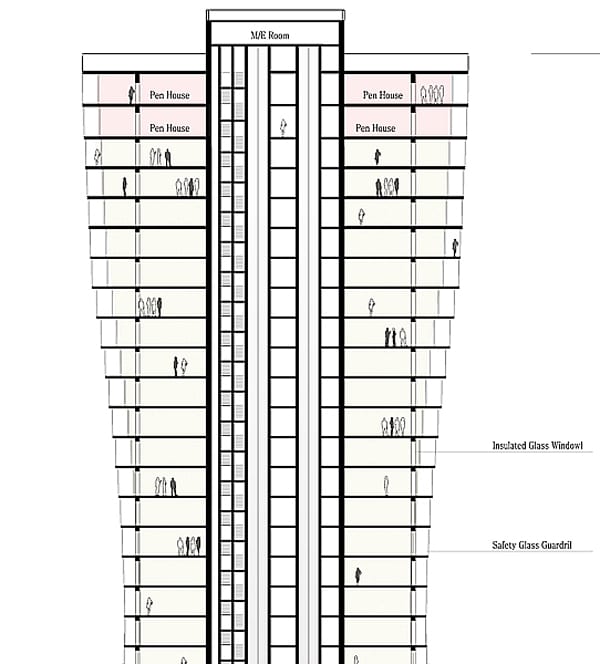

They were able to do so in about a year—longer than it takes to complete working drawings for an ordinary tall building, but still a feasible time frame—because Marilyn and her sister tower were actually less unusual than they looked in Ma’s renderings. Though every floor would have to be different from all the rest, each building was an uncomplicated composition of a central core, a relatively commonplace structure, and a façade that could be fashioned from ordinary window walls. “The skeletons are basically concentric,” Sigmund Soudack said, “and the only thing that articulates is the outside façade. In order to create the shape, we made the shear walls and columns move in and out, depending on the floor.”

The sinuous profiles of the towers—which are complementary, not identical—are created by rotations of the elliptical floor plates, between two and eight degrees per floor in the 56-storey original building, and four per floor in its 50-storey companion. These novel forms did invite some problems, Soudack said. One involved guaranteeing allowances for the high number of load combinations—more than 200 in all—that the buildings would have to withstand. Another consideration had to do with the marriage of the continuously wrapping balconies with the thermal joints under each window.

But, the engineer noted, with only a few exceptions—the concrete forming posed special challenges, for example—the systems, materials and technologies employed in ordinary high-rise construction were adequate for this job. Also, in most respects, Ma’s vision survived intact its transition from idea into reality—though not exactly. In the renderings supplied for the competition, Marilyn seems slender, sleek and tall. What was finally built is surely tall, but slightly more buxom than she was at the beginning. While remaining feminine and as zaftig as ever, she put on a little weight around the hips during the time she was being readied for her debut.

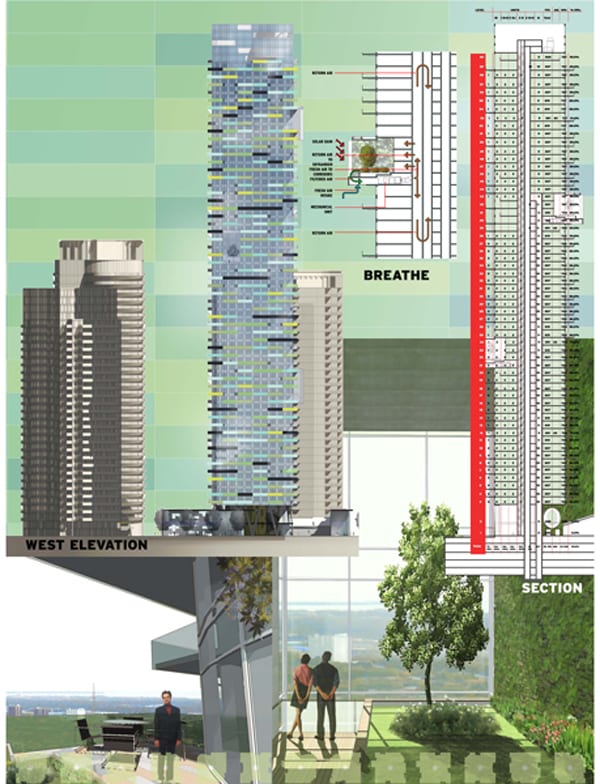

Be that as it may, the erection of the Absolute towers has indelibly imprinted on the Toronto-area fabric a controversial creative statement about the contemporary city that Canadian architects—especially the numerous “green” ones—should attend to.

“Green is good, we all like green,” Yansong Ma said in a telephone interview from his office in Beijing. “Green, sustainable buildings are very good, and we need them. But they are not enough. Cities now need nature, which is not only about sustainability.”

When Ma uses the word “nature,” I discovered over the course of several interviews with him, he means at least two things. One is actual greenery—trees and shrubs—stitched into the physical weft and warp of architectural objects. More importantly, however, the word signifies the incorporation of emotionally charged forms inspired by mountains and waterfalls and flowers, and, of course, by the contours of the human body. Nature, then, is “the spiritual dimension of reality,” an orchestration of naturally occurring shapes whose deployment aims to address the “emotional and spiritual needs of people, which are priorities now, as opposed to 50 years ago.”

In the architect’s view, contemporary cities in both East and West have become zones of alienation, because the large structures in them fail to echo the rhythms of natural things and processes. “I think there were great high-rise buildings many, many years ago, when people started building them. The high-rise became the symbol of the power of cities, and a great city needs tall buildings. But now, in the modern world, building high-rises…is not about a dream. It’s just a memorial for capital. When we build a strong building in a city, it is so cold. People feel disconnected from high-rises, since there is no concern for the human in them. Future cities do need high-rises, but they should be architecture for all people, gardens in the sky, and less about the mechanical.”

Ma regards Mississauga’s Absolute towers, which launched a career back in China that has been outstandingly successful, as eloquent digests of his beliefs about nature, architectural design and the city. His only regret—one shared by the developers—lies in the fact that no one in Toronto has pushed the initiative forward along the artistic and technical trajectory suggested by Absolute World. Another private-sector competition has not been held. No local real-estate company has inaugurated a condominium project that matches Absolute’s aesthetic daring.

Toronto developers, it should be said, belong to a notably risk-averse tribe: it would probably take more than a pair of towers to convince them of the market viability of voluptuous skyscraper forms. And, even if one could show that its formula has become stale (as Ma and other critics maintain), the orthogonal tall structure has an illustrious history as a city-building tool that seems far from exhausted. Western cities, at least for a while, will probably go on being as “square” as they’ve long been. It remains to be seen whether Ma’s large, decidedly non-square projects completed or under construction in China—some of them remarkably naturalistic and picturesque—will have any artistic impact beyond his home country’s borders. They just might: Ma`s office, MAD, is not yet 10 years old, after all, and the practical embodiments of his notions about nature have only just begun to emerge.

Meanwhile, Yansong Ma is pleased as can be by the commercial and critical success of Absolute World. “A lot of people live in there, so the towers don’t belong to one family or company, like a normal office tower,” he told me. “They show that a high-rise can avoid being a symbol for power. It can be place for people, and at the same time become an image for the city—an image about nature and the human. In these buildings, I was criticizing the boxes around them—not just in Mississauga, but also in North America, and also in China. I would like to see this project as a starting point to create new ideas about nature in the city.

–John Bentley Mays is an architecture critic and writes regularly for The Globe and Mail.

Client: Fernbrook Homes & Cityzen Development Group

Architects: MAD: Ma Yansong, Yosuke Hayano, Dang Qun, Shen Jun, Robert Groessinger, Florian Pucher, Yi Wenzhen, Hao Yi, Yao Mengyao, Zhao Fan, Liu Yuan, Zhao Wei, Li Kunjuan, Yu Kui, Max Lonnqvist, Eric Spencer; BURKA

Structural: SIGMUND, SOUDACK & ASSOCIATES INC.

Finalists

Roland Rom Colthoff, Quadrangle Architects Limited, Canada

Michel Rojkind, Rojkind Arquitectos, Mexico

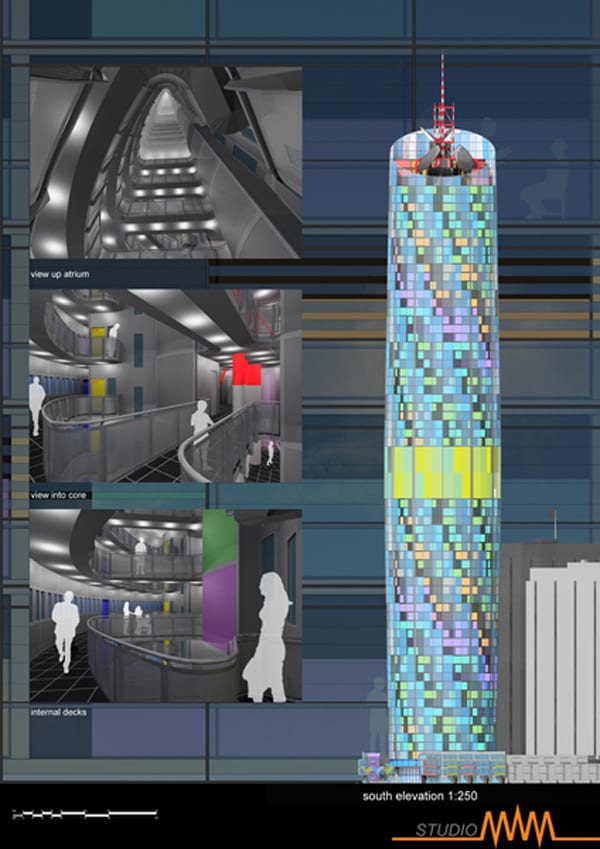

Sebastian Messer, Studio MWM, United Kingdom

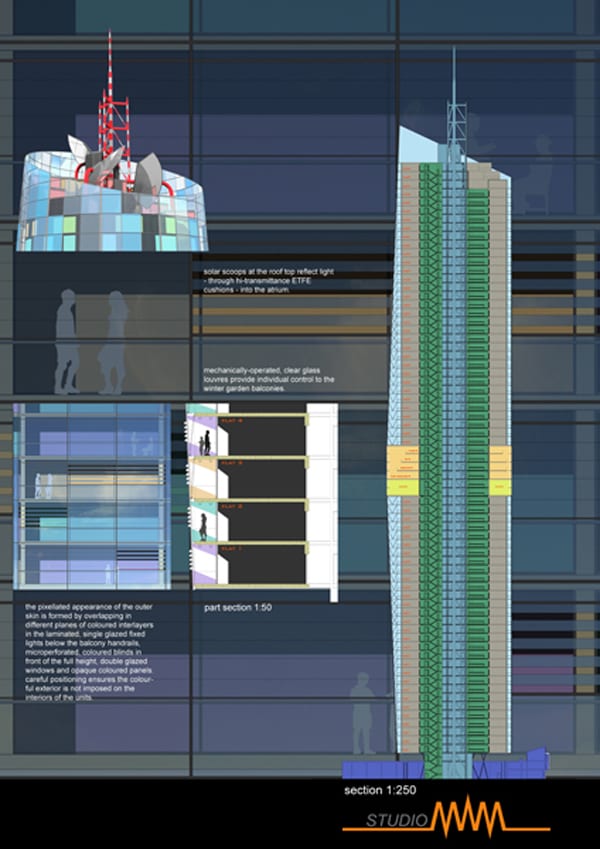

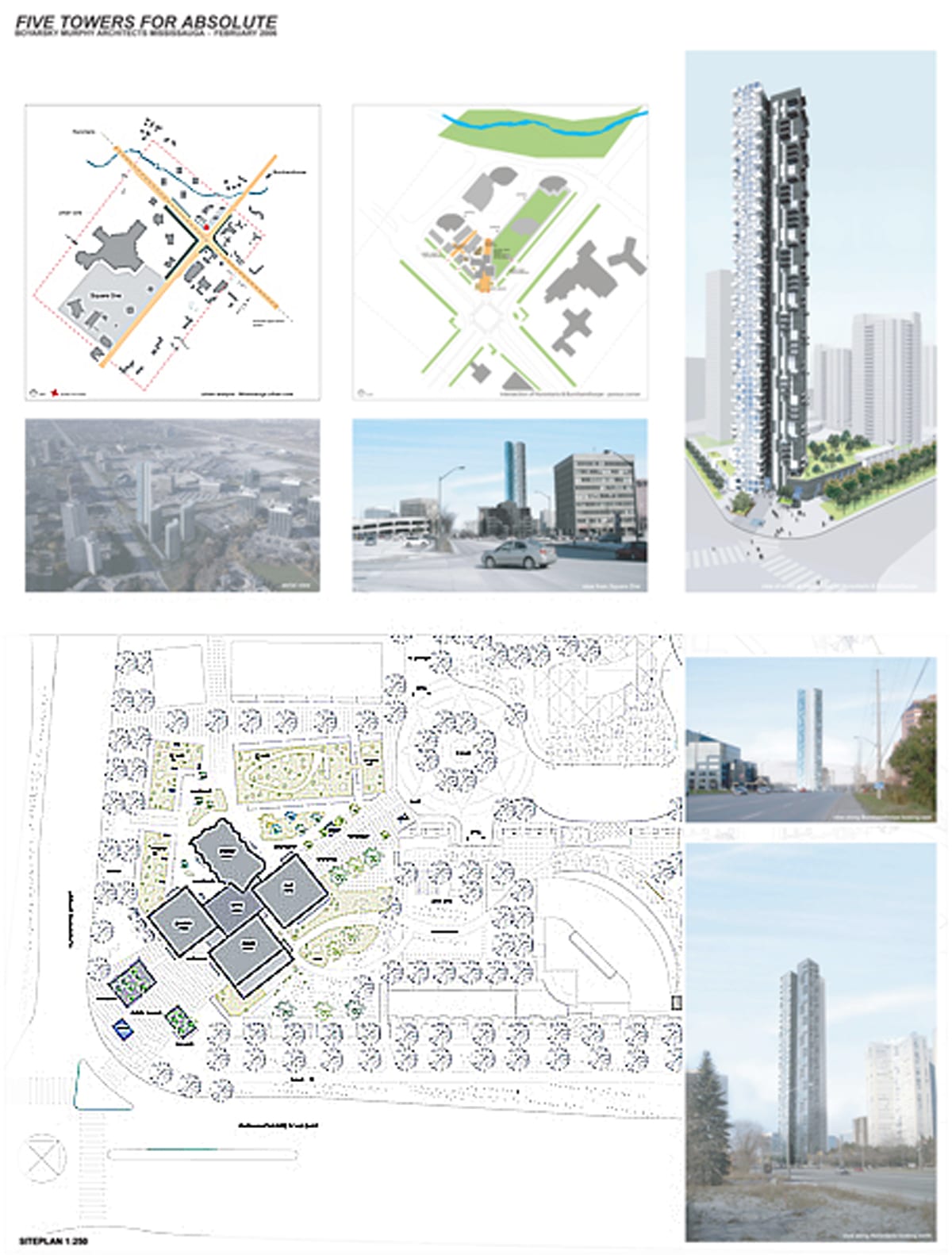

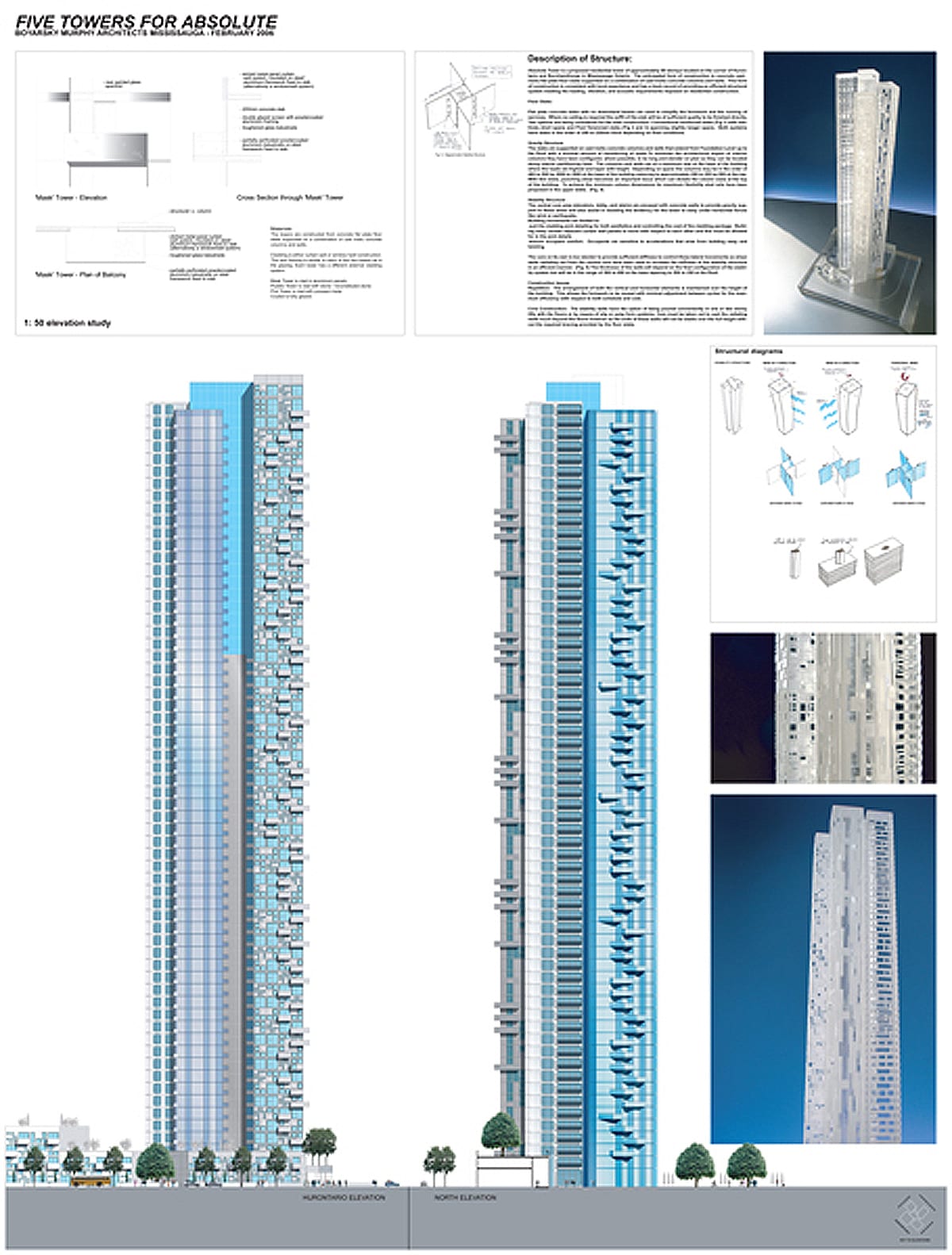

Nicholas Boyarsky, Boyarsky Murphy Architects, United Kingdom

Tarek El-Khatib, Zeidler Partnership Architects, Canada