By Stanley Collyer

On 2 July 2012, the A.M. Qattan Foundation (AMQF) launched an invited competition for the design of a new cultural and education center in Ramallah, Palestine. As a U.K.-based non-profit, which has focused on educational issues with emphasis on the Middle East, the Foundation’s Ramallah center has been located in an existing 80-year-old building for the past thirteen years, but feels that future demand for its services will require substantial expansion. By staging a competition for the new structure, AMQF is also seeking to “raise awareness about the role of built fabric design in improving the quality of urban life in social, cultural and economic terms.”

The A.M. Qattan Foundation serves a diverse community through its programs with a focus on teachers, children (mostly in Gaza through the Qattan Centre for the Child) and artists. Teachers are served through a wide range of training and research activities offered by the Qattan Centre for Educational Research and Development. They also benefit from resource development activities and library services.

Artists from all the creative fields benefit not only from the grants, awards and scholarships offered by the Culture and Arts Program, but also from the facilities and equipment available to experiment, develop and share their artistic productions.

The Centre also sponsors public activities in culture, the arts and education on a regular basis. These include lectures, book launches and discussions, exhibitions, concerts, workshops, theatrical production (on a small scale) and film screenings. Although the library targets teachers in particular, its services are extended to researchers, artists and other interested members of the public.

The Site in Ramallah

Architecture in Palestine has undergone several changes during the 20th century.

With the advent of modern technology, cement replaced lime as a binding material, and steel beams were used for the first time. Buildings in the West Bank and Gaza Strip adopted modern construction techniques, which left an impact on their form and details, though stone was still used in new applications such as external cladding. Until the Oslo accords in 1990 and the arrival of the Palestinian Authority, Ramallah could be characterized as a small town with a population of about 6,000. After the building boom of the past two decades, financed in large part from Palestinians living in the Diaspora, the city’s population now exceeds 30,000, and it has become the main administrative and economic center in the West Bank. Urban sprawl has been one result of this population explosion, much of it similar in appearance to the Jewish settlements.

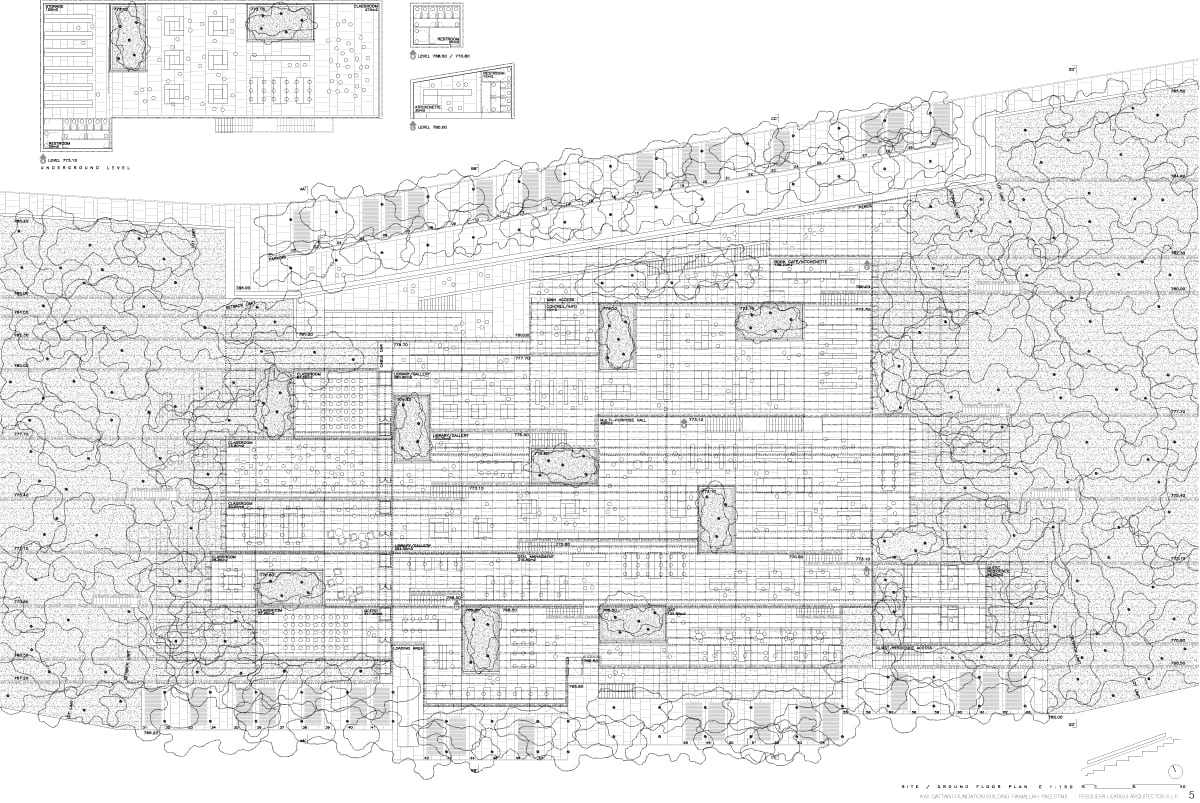

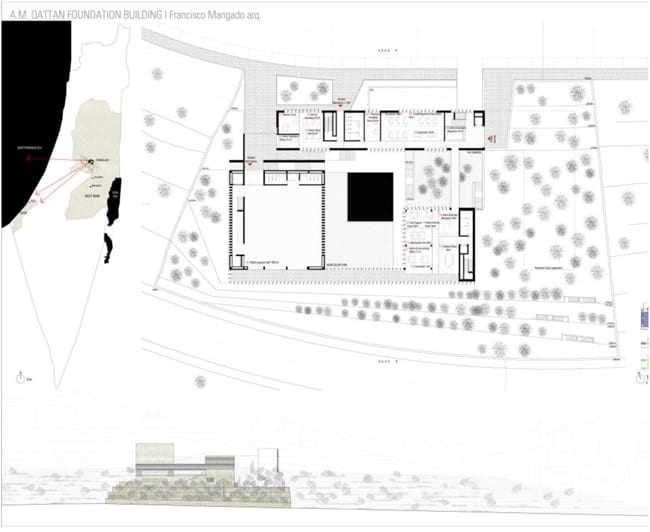

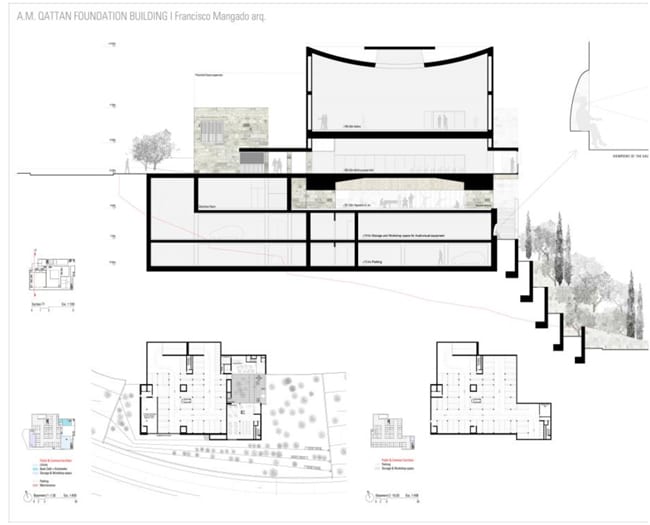

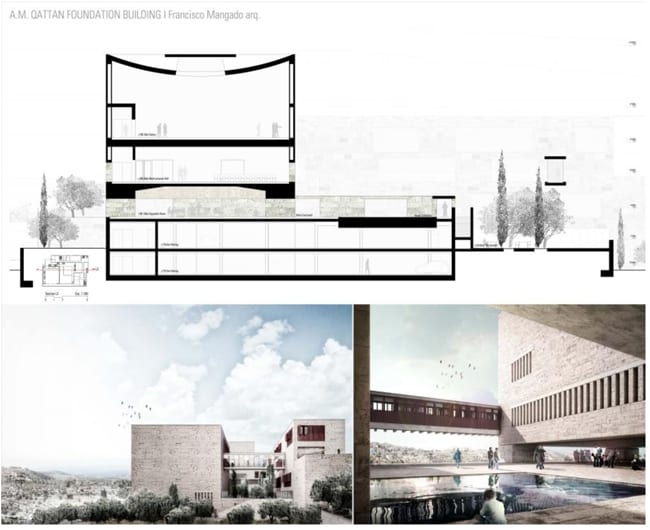

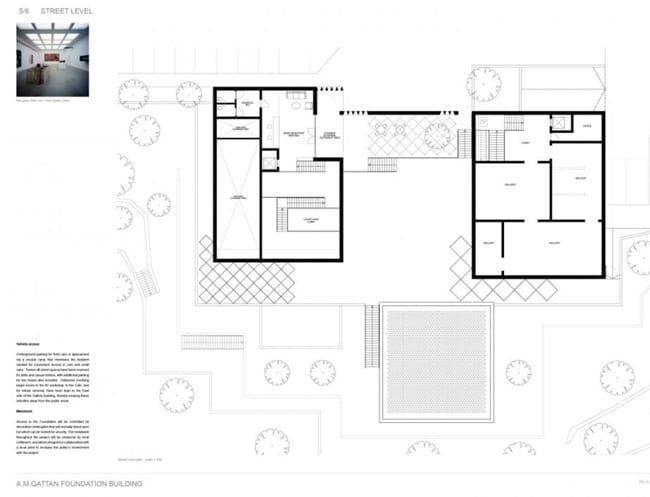

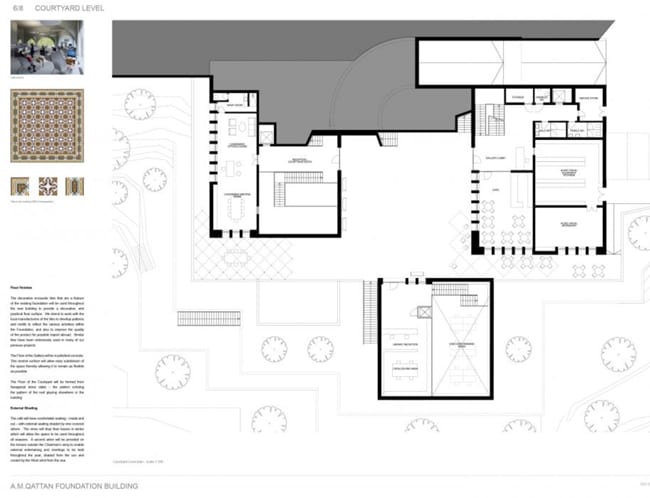

The building site for the competition is a 5,864m2 plot of land owned by the AMQF in the Tireh neighborhood of Ramallah. The site offers unimpeded views to the east, south and west, with the coastal plains to the west visible on a clear day. The lot is on the southern slope of a hill, one of its neighbors being a Women’s Community College.

Program

Besides accommodating the main office for the Qattan Centre, public facilities to be included are a multi-purpose hall, art gallery, library and book café. The building is intended “both as a landmark and a flagship for cultural production and development in which people can freely interact, share, access information and project their ideas. It must embody the values of the Foundation with its forward-looking commitment to innovation, originality and artistic flair while acknowledging the past in all its rich complexities.” Besides allowing for additional construction in the future, there should be strong emphasis on sustainability with the lowest possible environmental impact. To maximize space efficiency, common areas and their components must be flexible so that they can serve both general management needs and individual programs. The anticipated budget for the structure (without architectural fees) is projected at $4.5M.

The Competition

The jury, which met at Birzeit University on the West Bank, was composed of:

• Shadia Touqan (architect);

• Caecilia Pieri (editor at Editions du Patrimoine, Paris);

• Khaldun Bshara (architect);

• Omar Yousef (architect);

• Ziad Khalaf and Omar Al-Qattan (the latter two being respectively the Foundation’s executive director and Board of Trustees secretary).

The four finalists were shortlisted as a result of an RfQ. They were:

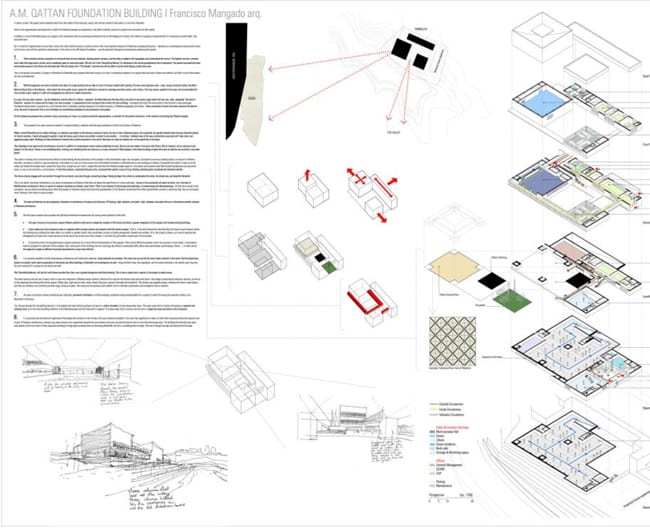

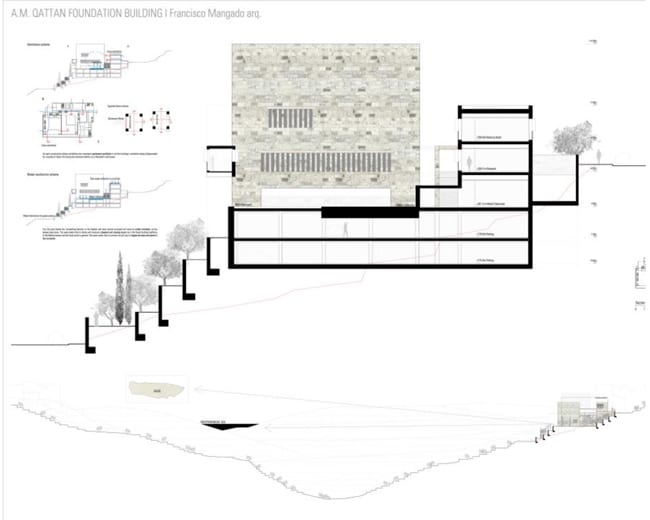

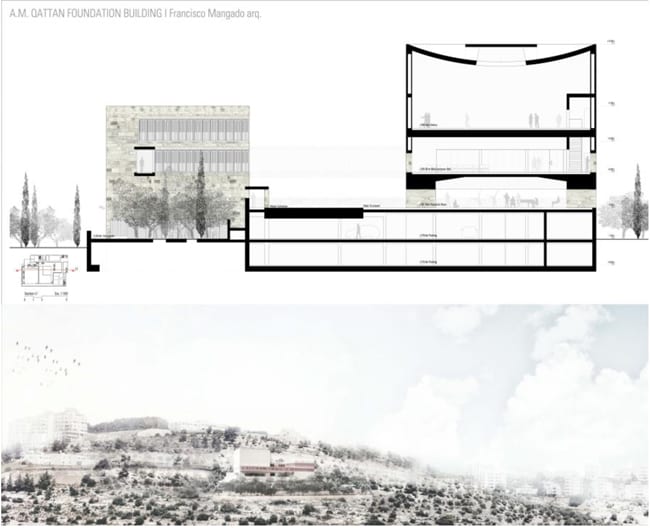

• Francisco Mangado Arquitectos, Pamplona, Spain

• MRJ Rundell and Associates, London, U.K.

• Pesquera Ulargui Arquitectos, Madrid, Spain

• Donaire Arquitectos, Seville, Spain

After the four firms made 90-minute presentations to the jury, the jury convened to discuss the ranking of the projects. The adjudication process resulted in a 5 to 1 vote in favor of Donaire Arquitectos, with Pesquera Ulargui Arquitectos a close second due to the originality of the scheme. The other two finalists were commended for the “depth of their research and the sophistication of their proposals.”

The Winner

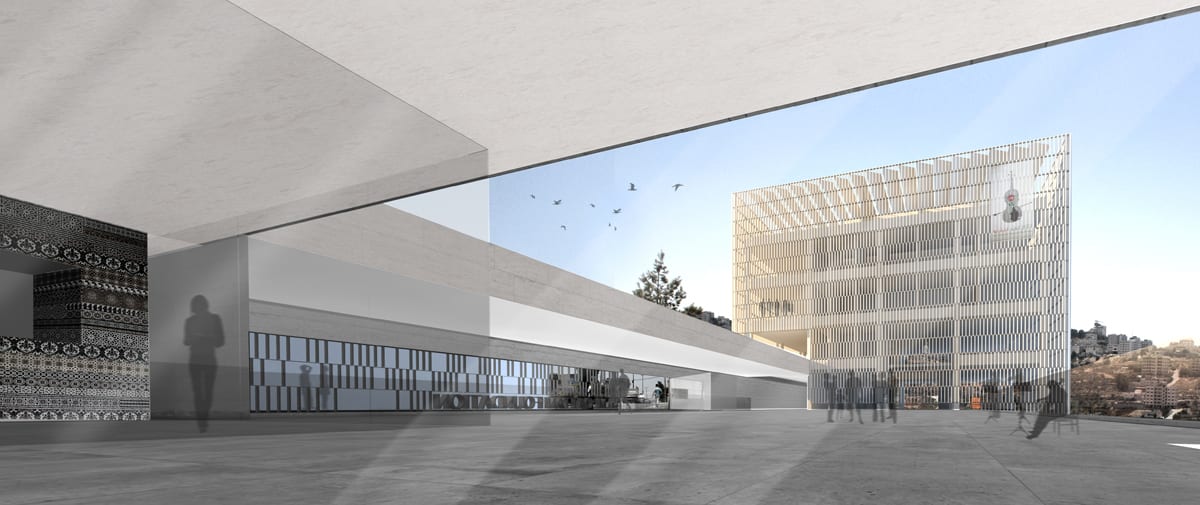

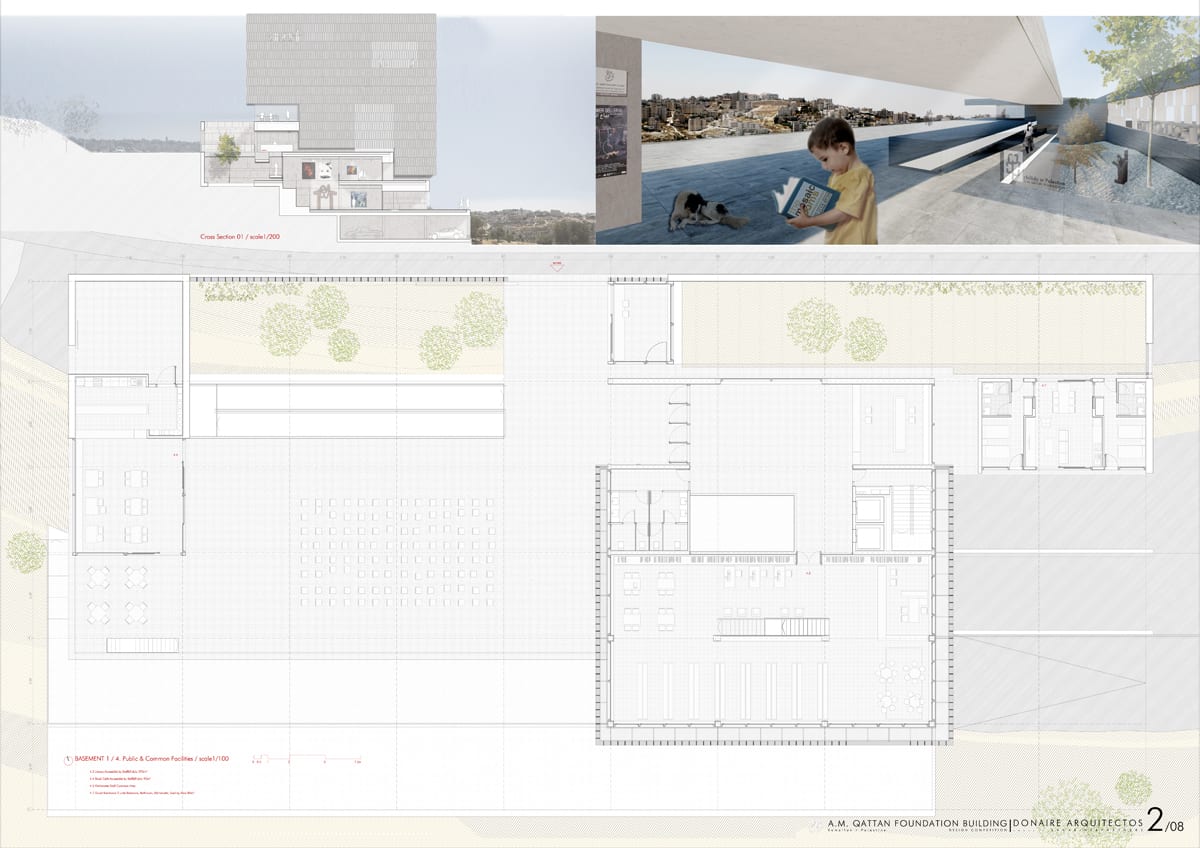

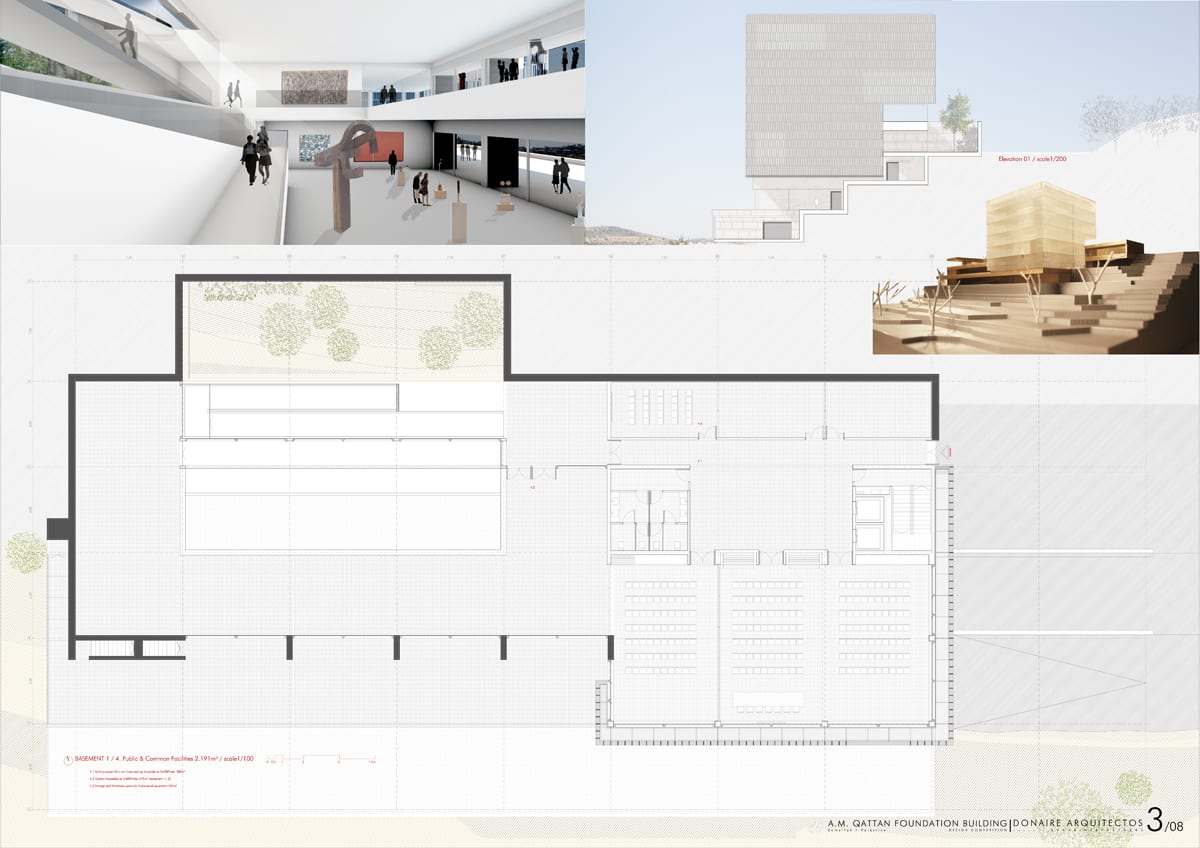

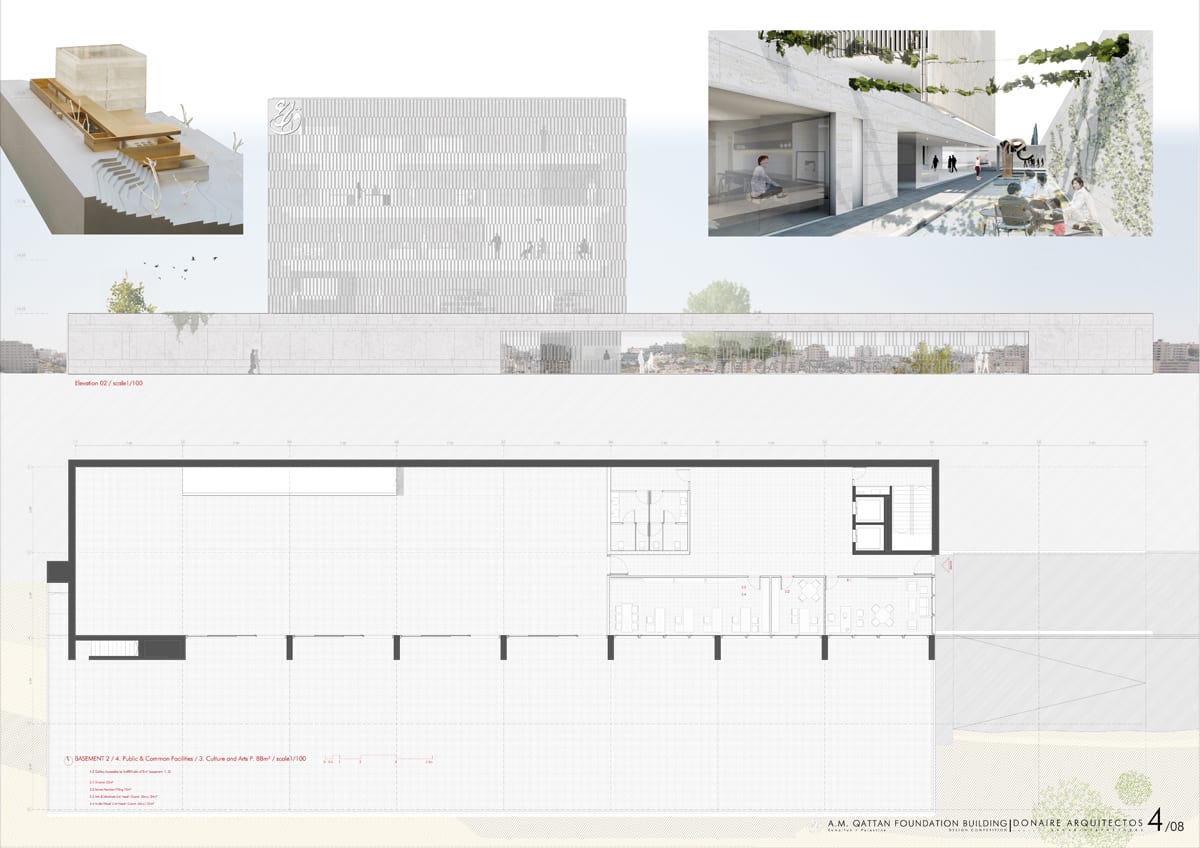

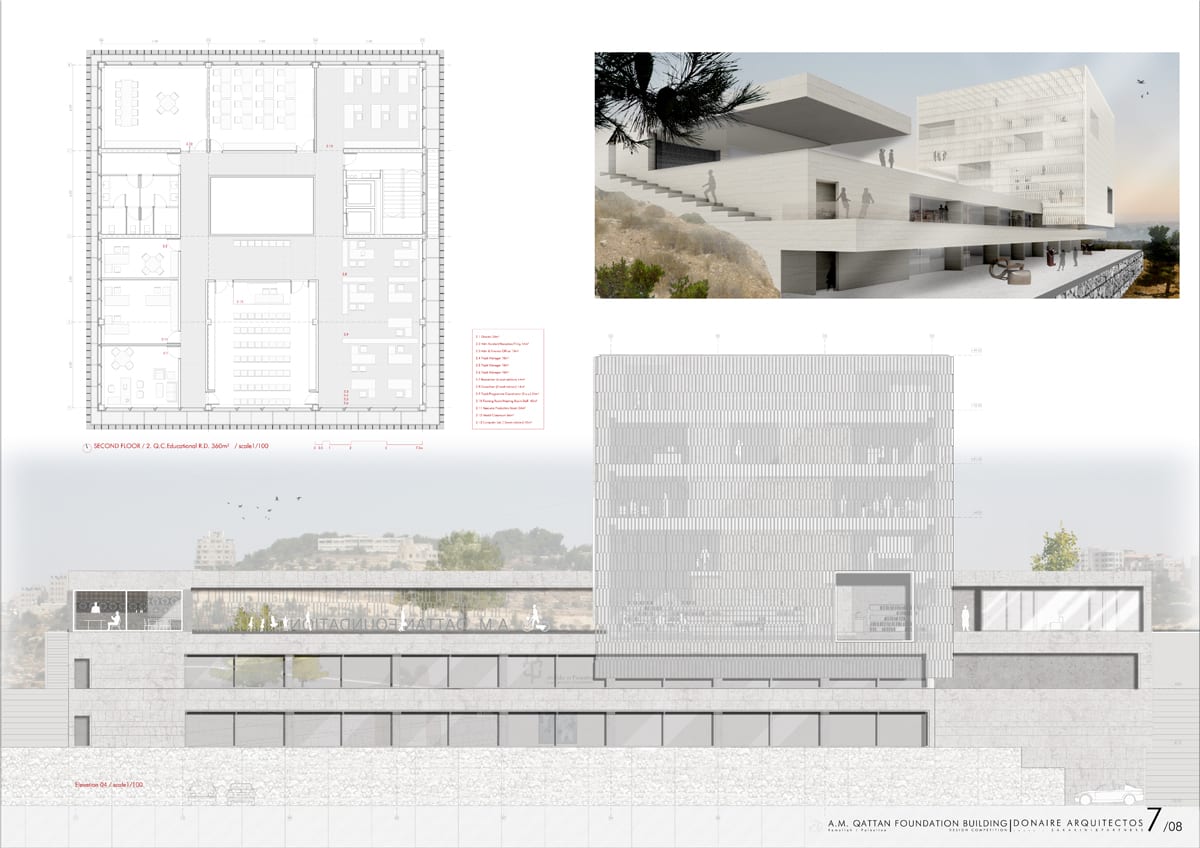

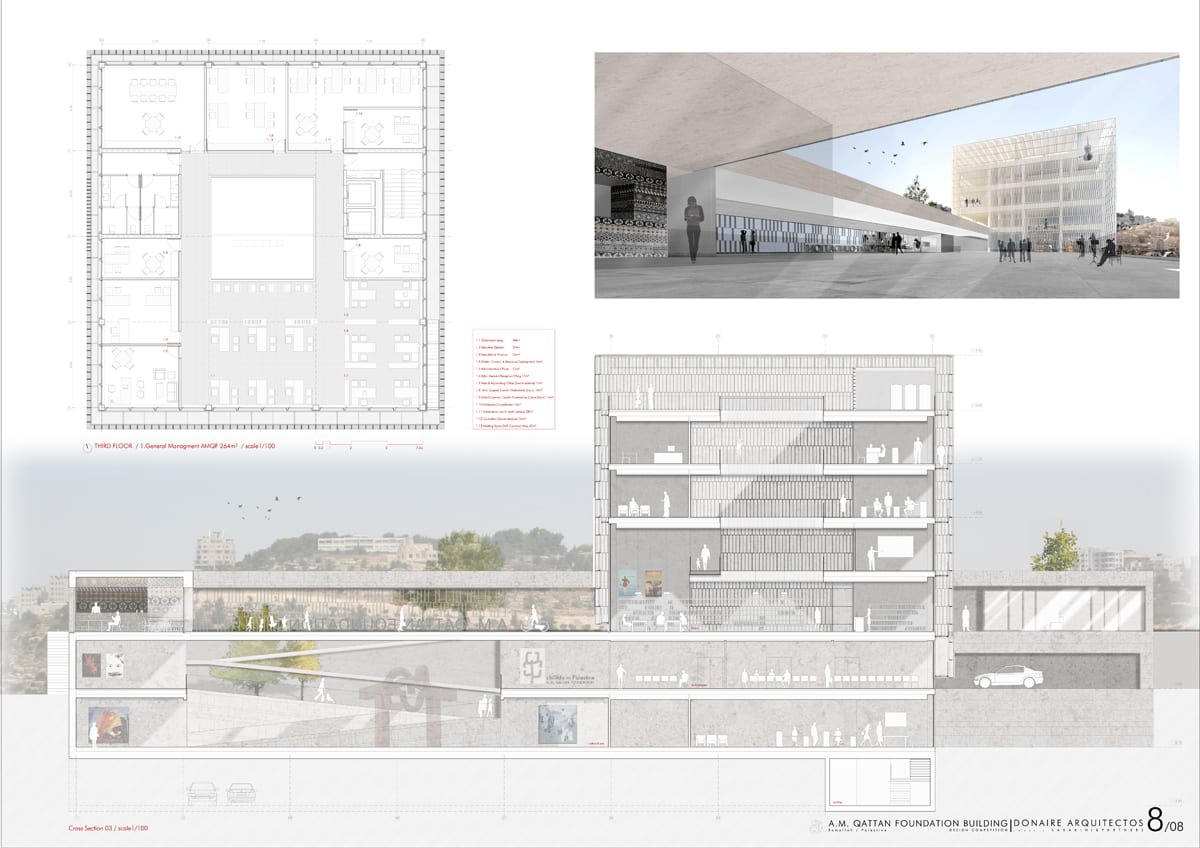

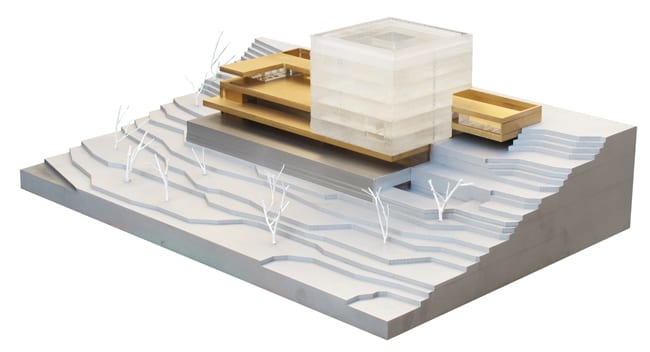

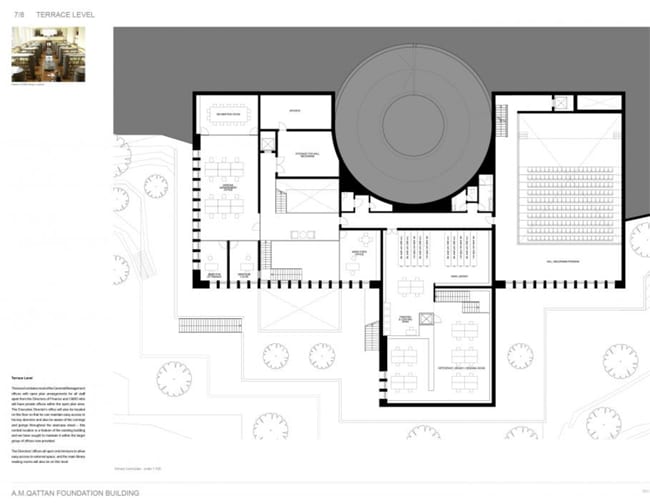

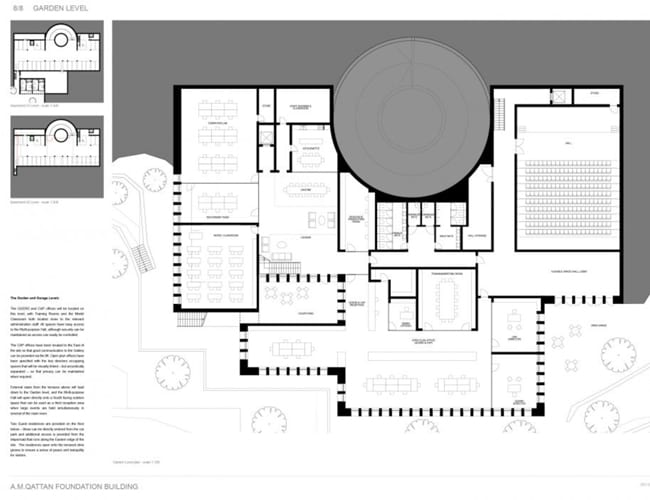

The jury felt that the Donaire Arquitectos proposal was the most functional and flexible of the four designs, while also enjoying a degree of elegance and beauty in a number of its aesthetic choices. The architects had undoubtedly found the best solution for the challenging spatial requirements of the brief, opting for a solution that was neither bulky and overbearing nor over-subtle and unmanageable. Their future expansion scheme was commendable.

Connections between different spaces, particularly the private and public areas and various levels/floors were properly thought through with the user and visitor very much at the centre of the architects’ solutions, rather than any theoretical preoccupations. The Jury also felt this to be a worthy advocate of the Foundation: inviting, elegant, spacious, unpretentious and on a thoroughly human scale.

Among the reservations about their entry were the proposed use of stone louvers on the main block, with a secondary glass façade, which worried the Jury in terms of future heating and cooling costs and carbon emissions. Secondly, the terrace, while visually stunning, also posed its own set of problems, both in winter and summer. There was also concern about the seemingly impractical shape of the gallery.

-Jury Comments

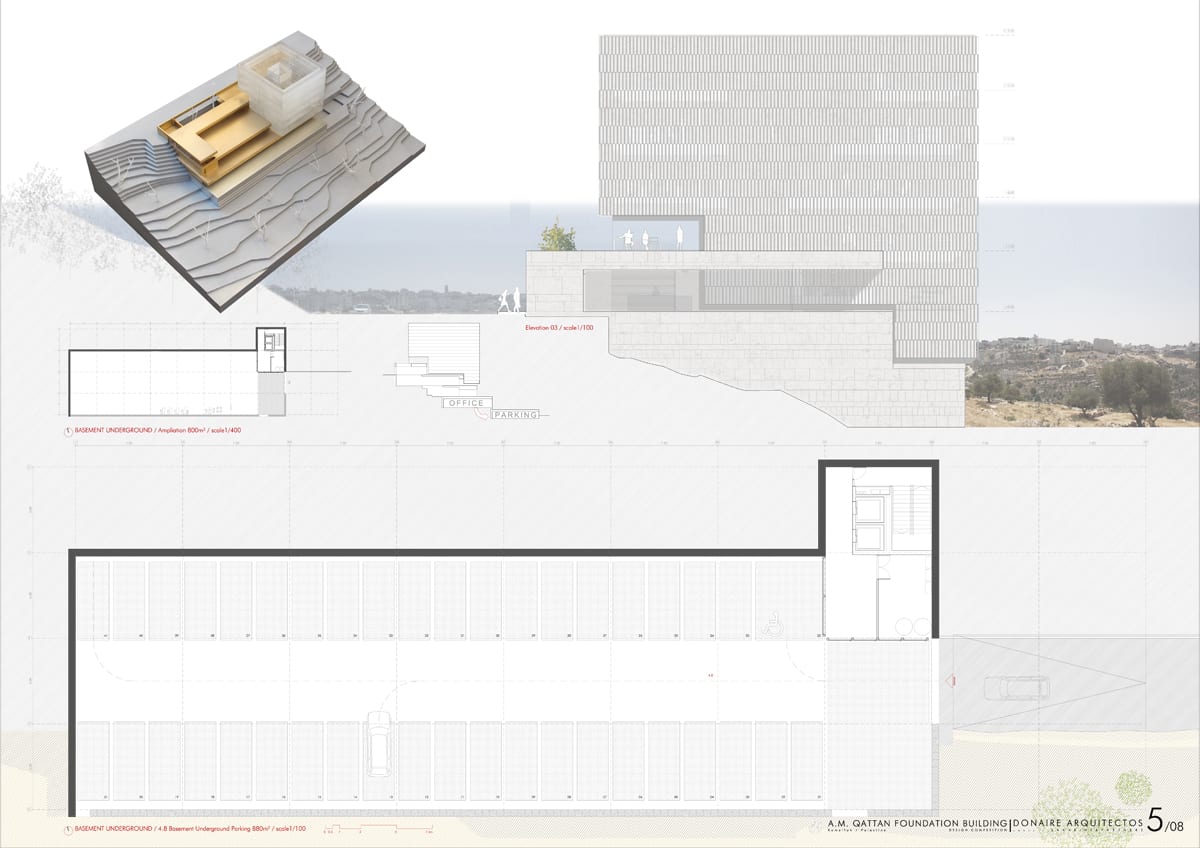

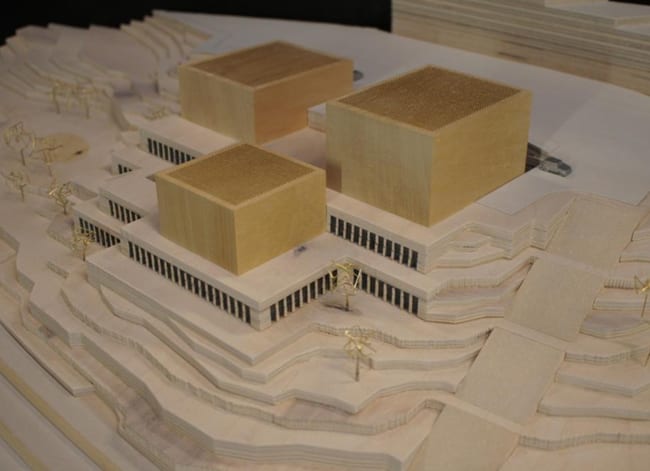

Presentation boards and model by Donaire Arquitectos (click images to enlarge)

Runner-up

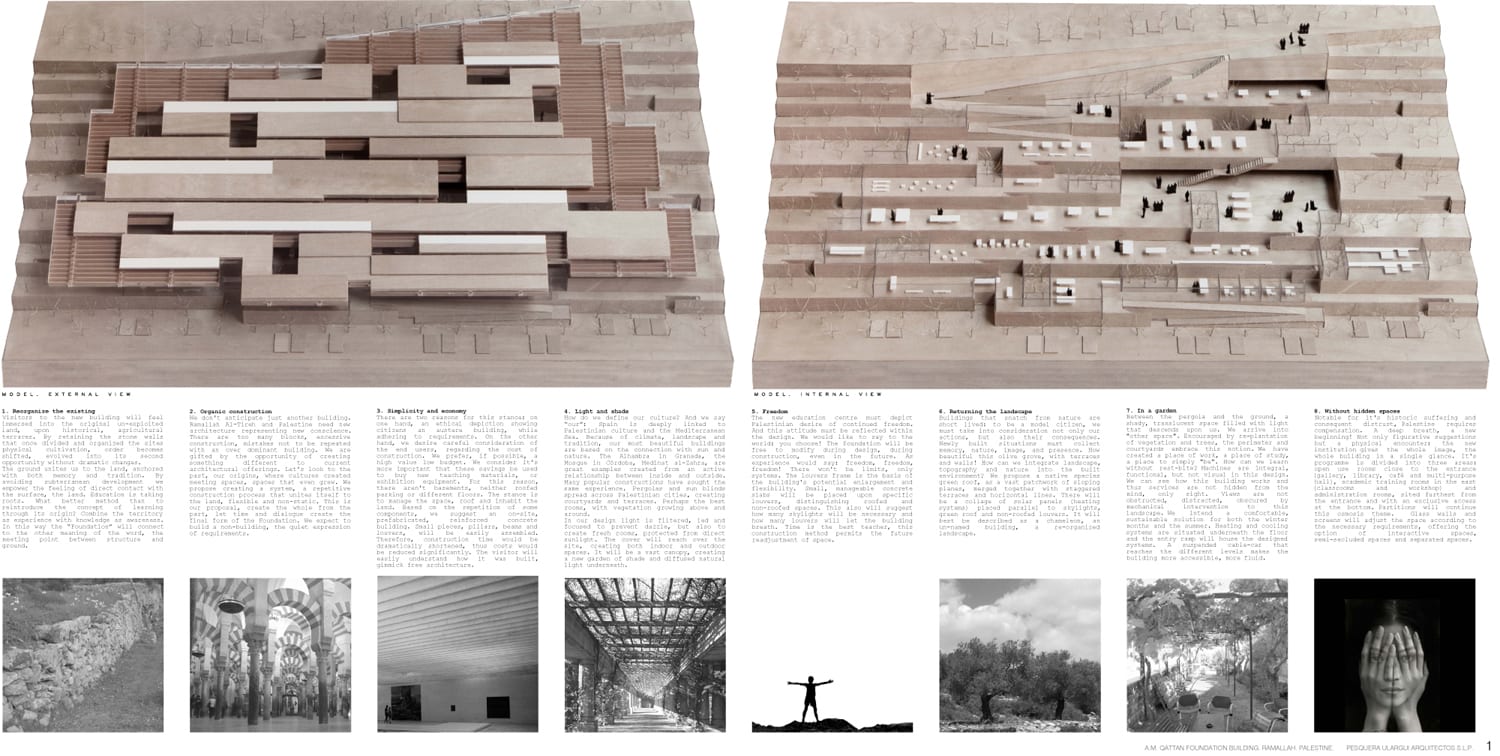

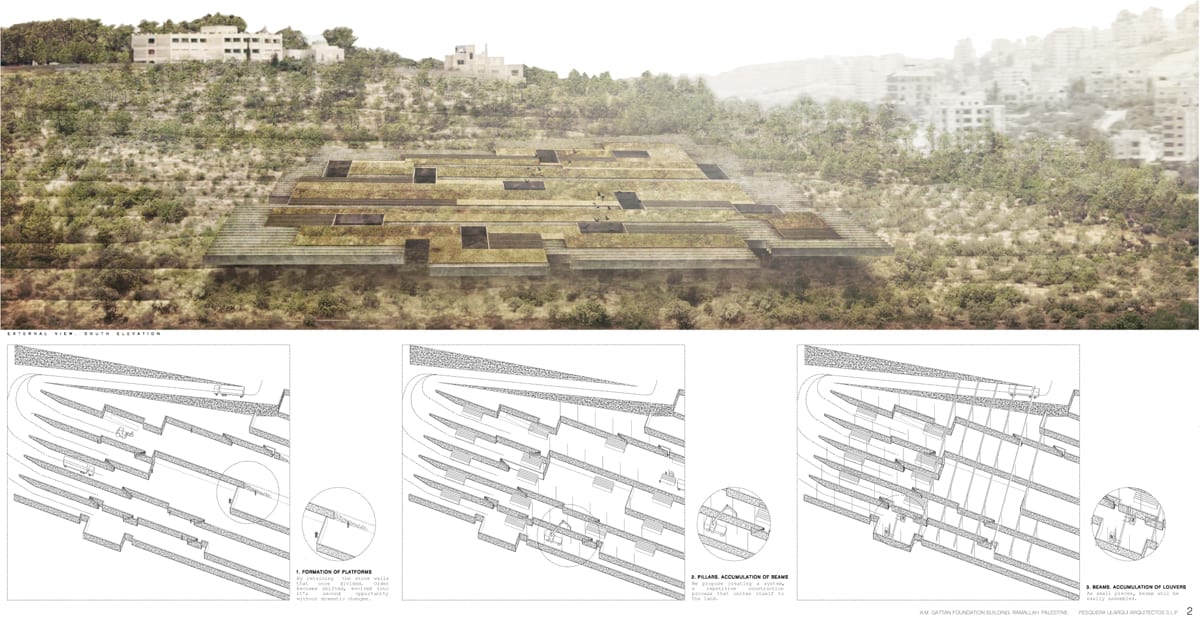

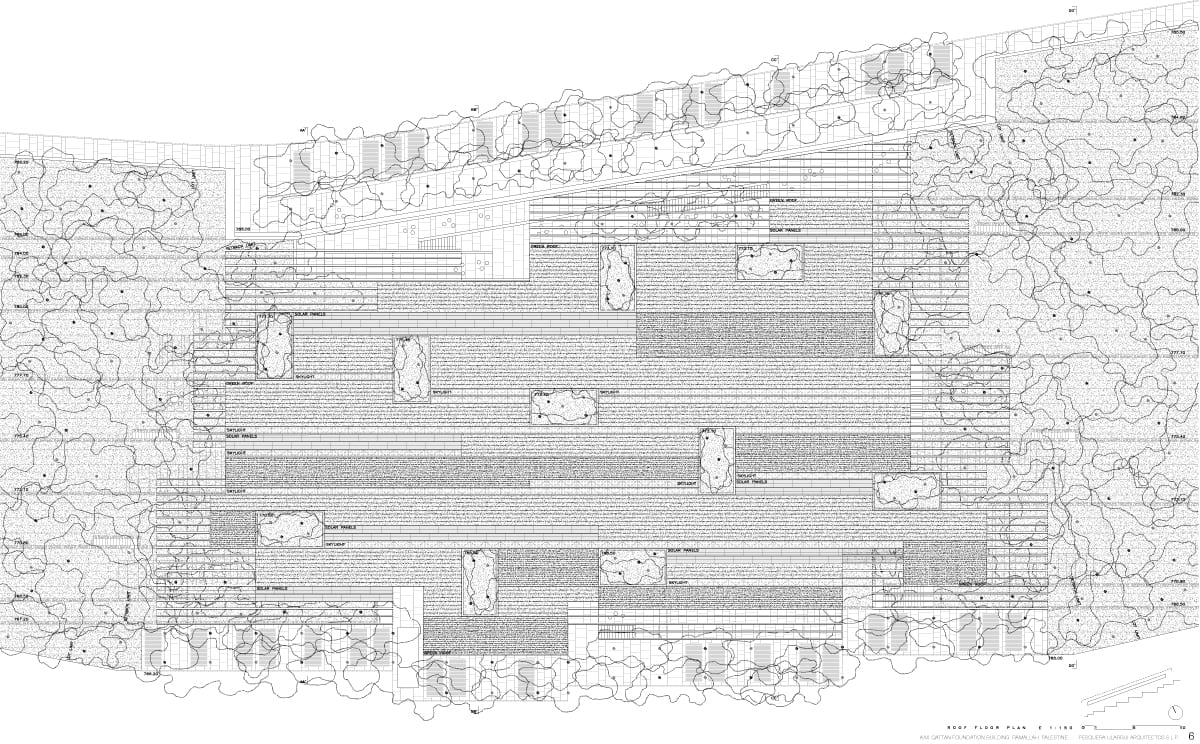

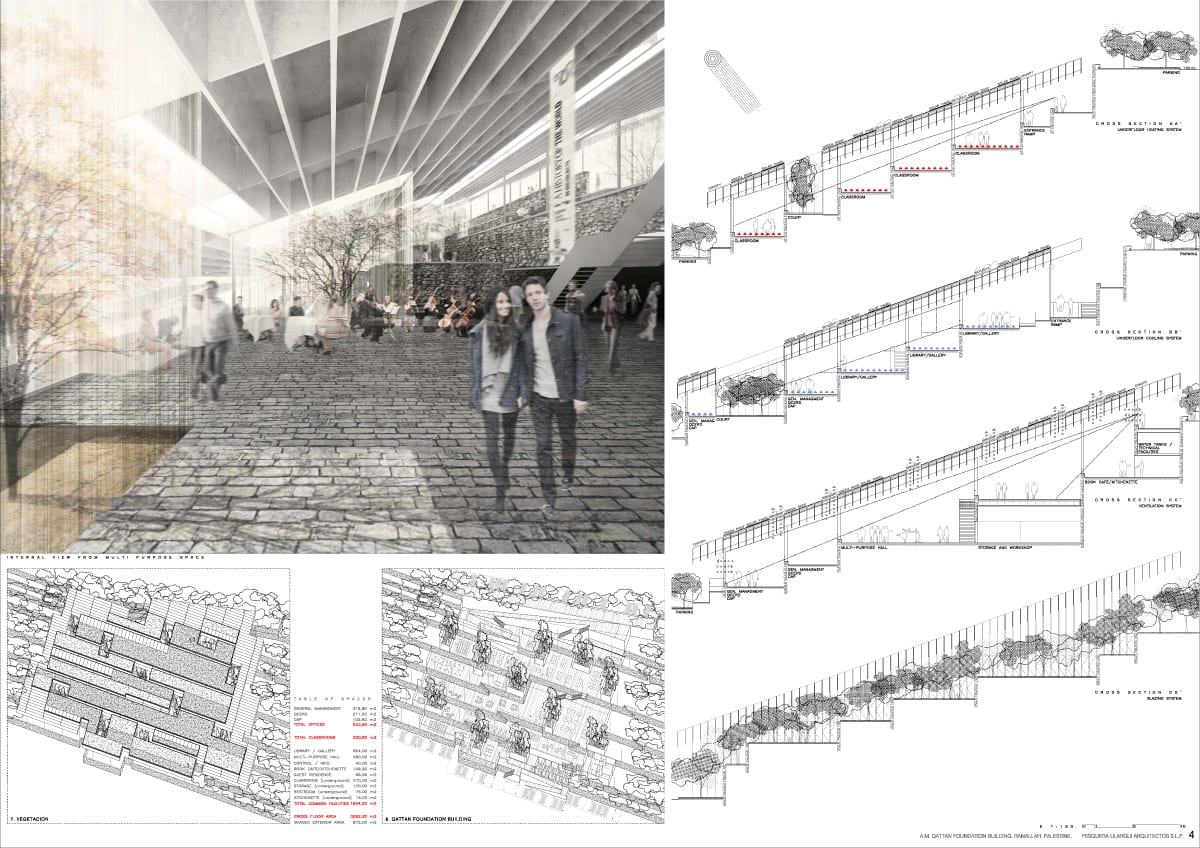

Pesquera Ulargui Arquitectos

The Jury was divided on the qualities of this design, with one group commending its originality, uniqueness, ambition and courage in daring to propose totally unexpected and unconventional ideas and a very special quality to the interior space. Its respect for the landscape and the exquisite subtlety of its design were particularly appreciated.

Some jurors, however, felt that the design’s principle idea was too removed from the local context, or too subtle to make sense in Palestine. However, several factors also spoke against the proposal’s argument. First, while the proposal argued for an “anti-landmark landmark,” which would be characterized by its subtlety in comparison to the aggressive, anti-aesthetic salience of most contemporary buildings in Ramallah, some jurors felt that it was antithetical to the brief’s requirement for the building to have an unmistakably visible (rather than an over-subtle) identity.

Secondly, there was strong concern about local ability to build such a building, with its very precise specifications for prefabricated components. Other major concerns were about insulation, airflow and convection in a building that would be so open yet simultaneously populated by both office workers and visitors. The building seemed also to have no “spine” and the proposed highly visible elevator would only have been a continual distraction for its users. Finally, the distribution of spaces struck the Jury as highly impractical.

While the Jury felt confident that the architect would be more than capable of finding some solutions to these problems, given their previous record, there were too many other serious concerns with their proposal. Therefore, with the exception of one vote, the Jury decided to exclude it.

-Jury Comments

However, the “surprise” idea, though intriguing, did not seem to have been fully articulated in the actual circulation, which struck the Jury as confusing. The divisions between programs and between the public and private office spaces were not always clear. The café and garden seemed isolated, while the guest residences were positioned strangely adjacent to the front entrance. Other major concerns included the lack of a foyer outside the multi-purpose hall; and huge spans which appeared to the Jury as both technically and financially onerous. Finally, on a purely aesthetic level, the fortress-like structures appeared forbidding rather than inviting, and the inclusion of a long footbridge to connect the structures seemed unappealing and wasteful.

–Jury Comments

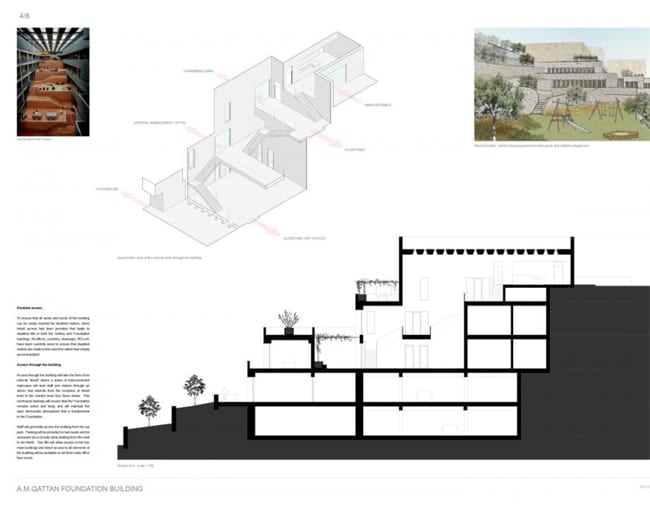

Finalist

MRJ Rundell and Associates of London were complimented by the Jury for the quality of their research into the local and regional idioms, particularly traditional building techniques and materials, although it was occasionally confused by alternate references to Egyptian and Turkish-Ottoman architecture. This proposal struck the Jury as highly pragmatic and detailed, with relatively simple and functional ideas. Of the four designs, the Jury also felt that this had made the best use of the site. The team also proposed careful and sensible solutions for shading and an interesting use of mass.

However, the Jury felt that the design lacked in vision and panache what it offered in pragmatism. The central courtyard idea, for example, seemed academic and dry. It also failed to use the views to the valley by placing a building in front of the visitor’s line of vision, without achieving the elegant coziness of a traditional courtyard.

Once again, the fortress-like aesthetic seemed forbidding rather than welcoming and the wall-like entrance, with its adjacent parking ramp, made the building uninviting.

-Jury Comments

Presentation boards and model by MRJ Rundell & Associates (click images to enlarge)