by Dan Madryga

The landscape of waste: it is a common feature in any big city. Left in the wake of decentralized cities and waning industry, the neglected postindustrial terrain is an unavoidable blemish on the built environment. The desolate, ugly, contaminated vestiges of abandoned factories, overstuffed trash dumps and discontinued mills were pushed out of site and out of mind for decades as Americans sought refuge in suburbia. Yet as urban centers are gradually redeveloped and society expresses increased concern about environmental crises, these harmful, marginalized sites are becoming more difficult to ignore. On Brooklyn’s doorstep lies one such wastescape: the dormant and noxious Gowanus Canal. With help from the recent Gowanus Lowline ideas competition, locals are beginning to seriously contemplate a restorative future for this type of ailing urban environment.

Brownfield redevelopment remains a relatively new urban design issue, and like any formative typology, the strategies and theoretical framework must continue to improve. From landscape architect Richard Haag’s groundbreaking decision to incorporate the industrial remnants of a derelict gasification plant into Seattle’s Gasworks Park in 1975, to the conversion of Vienna’s Gasometer project to retail residential in 2001, the treatment of the postindustrial landscape has been gradually refined as new ideas are pioneered. Or take, for example, Peter Latz und Partner’s 1999 conversion of Duisburg, Germany’s Thyssen Steelworks into the innovative Duisburg Nord Landschaftspark. In contrast to the cordoned-off, stylized nature of Gasworks Park, Latz’s immersive design reappropriates factory relics for new functional uses with a minimum of interventions, creating a more palpable connection between industrial past and recreational present. In this manner the treatment of the postindustrial landscape continues to mature, and now the Gowanus Lowline competition presents a valuable and timely opportunity to carry on this important evolutionary discourse. This sort of challenge is ideally suited to a provocative ideas competition, and the Gowanus Canal provides a perfect case study.

It is not surprising that the Gowanus Canal and its environs constitute one of the few underdeveloped areas of increasingly vibrant Brooklyn, New York. Constructed in the mid 19th century as a key transportation and commercial link between Brooklyn and New York City, the banks of the canal quickly became host to a toxic assortment of gas plants, paint factories, mills, and coal yards. The ensuing decades took their environmental toll and left the waterway brimming with poisonous discharges of industry. The result is a murky, malodorous, literally lifeless waterway that continues to pose serious environmental and health threats long after the factories and mills were boarded up. The EPA has deemed the canal “one of the nation’s most extensively contaminated water bodies,” and in March 2010 added the site to the Superfund National Priorities List to facilitate extensive investigation into its problems.

While the federal government invests its own interest in the troubled site, a steady increase in local efforts has paved the way for the Gowanus Lowline Competition. This open, international ideas competition was organized by Gowanus by Design, a non-profit organization founded by local architects David Briggs and Anthony Deen and committed to seeking creative and restorative design solutions that point to a brighter future for the canal and its neighboring community. The first of a planned series of canal-centric design exercises, Gowanus by Design’s inaugural competition, subtitled “Connections,” revolves around a single question: “How do you define connection(s) relative to the Gowanus Canal and secondly, how is this understanding realized?”

Although this simple premise may seem a bit general, the physical, demographical, and ecological circumstances of the canal site essentially speak for themselves in establishing a design challenge: balancing environmental remediation with the creation of a livable community connected to its urban environs is a top priority. And by keeping the program open-ended, Gowanus by Design attracted a diverse a range of ideas that will hopefully spark an engaging dialogue concerning the future possibilities of this post-industrial landscape.

The competition attracted an impressive response with 188 entries from 14 countries. Local interest was also evident considering that 26 of the submissions were from Brooklyn-based teams. A jury primarily consisting of local talent whittled this sizable collection of ideas down to a First and Second Prize (awarded $1000 and $500 respectively) and four Honorable Mentions. The jury included:

- Julie Bargmann, DIRT Studio, Landscape Architect

- David J. Lewis, LTL Architects, Architect

- Gregg Pasquarelli AIA, Principal SHoP Architects

- Richard Plunz, Columbia University GSAPP

- Andrew Simons, Chairman, Gowanus Canal Conservancy

- Joel Towers, Dean of Parsons The New School For Design

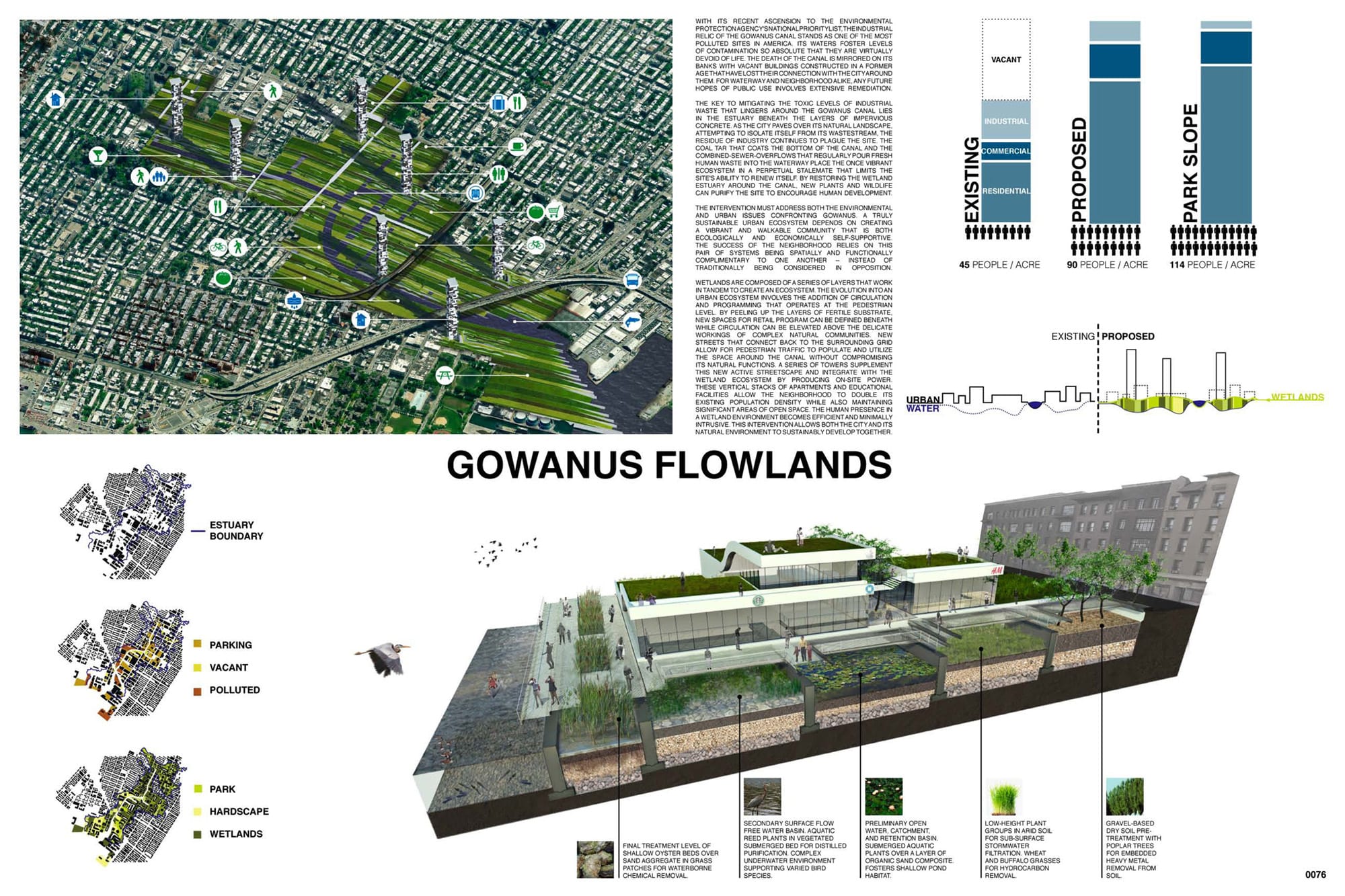

First Place Prize:

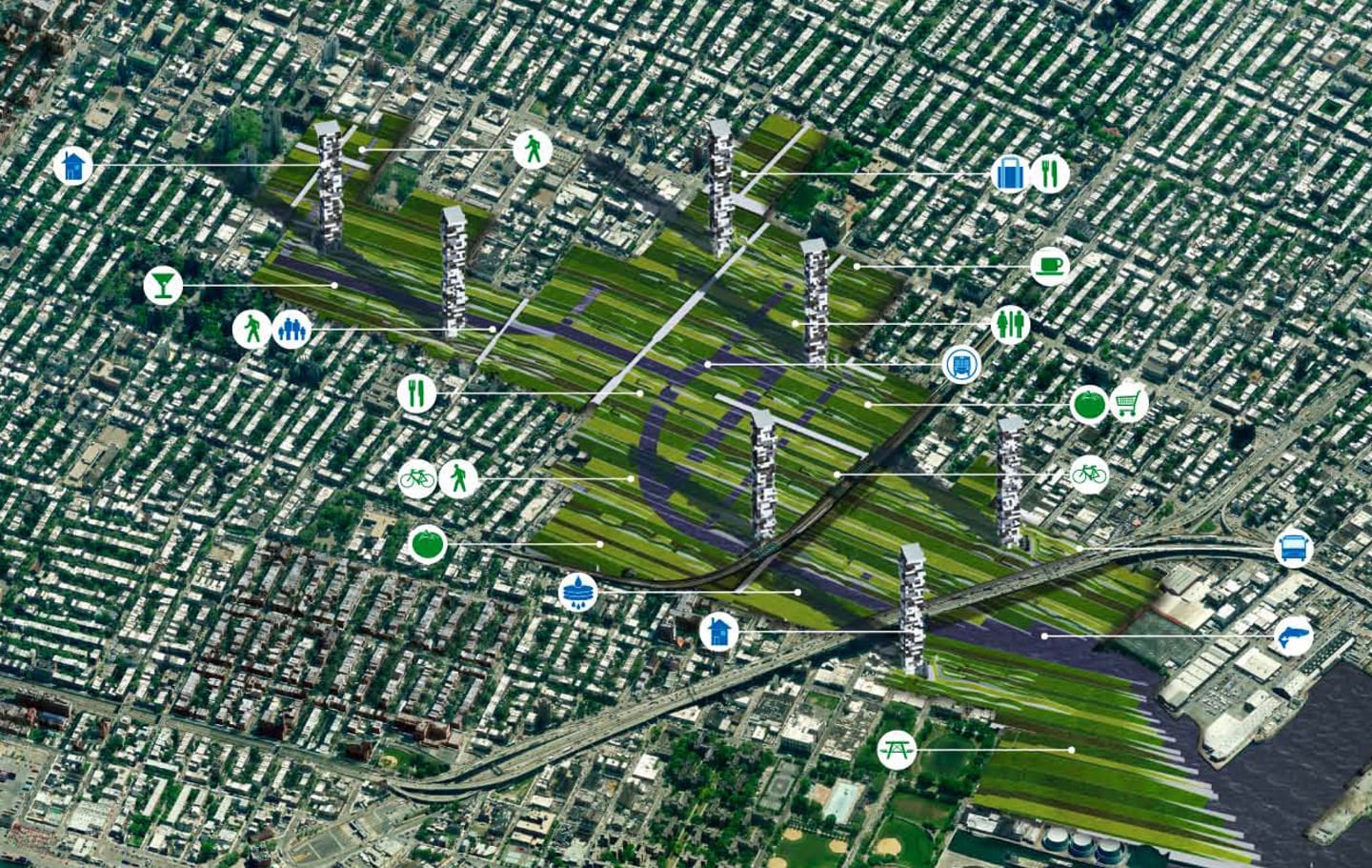

Project: Gowanus Flowlands

Team: Tyler Caine, Luke Carnahan, Ryan Doyle, Brandon Specketer, New York

The winning team, hailing from New York, operated on the premise that a successful intervention must address dual problems of the Gowanus Canal: environmental contamination and urban depopulation. “A truly sustainable urban ecosystem depends on creating a vibrant and walkable community that is both ecologically and economically self-supportive. The success of the neighborhood relies on this pair of systems being spatially and functionally complementary to one another instead of traditionally being considered in opposition.”

The team has essentially created an urban wetland – a complex, well-detailed filtration ecosystem seamlessly interwoven with a network of pedestrian circulation paths, recreational spaces, and retail and commercial buildings tucked underneath vegetated roofs. The jury was pleased with this unique integration, noting that it “presents a more compelling urban condition and suggests a new type of urban landscape that suggests living with remediation.”

The ecological and urbanistic functions in this project are handled so well that the team’s decision to cap this intricate landscape with seven identical, evenly spaced high-rise residential towers seems a bit of a retrogressive misstep. The idea to introduce a bit more population density to the canal site is certainly welcome, but the execution recalls a bit too uncannily the old Radiant City, towers-in-a-park modernist concept of urbanism. Yet given the overall excellence of the design scheme, this is a minor complaint.

Second Place Prize:

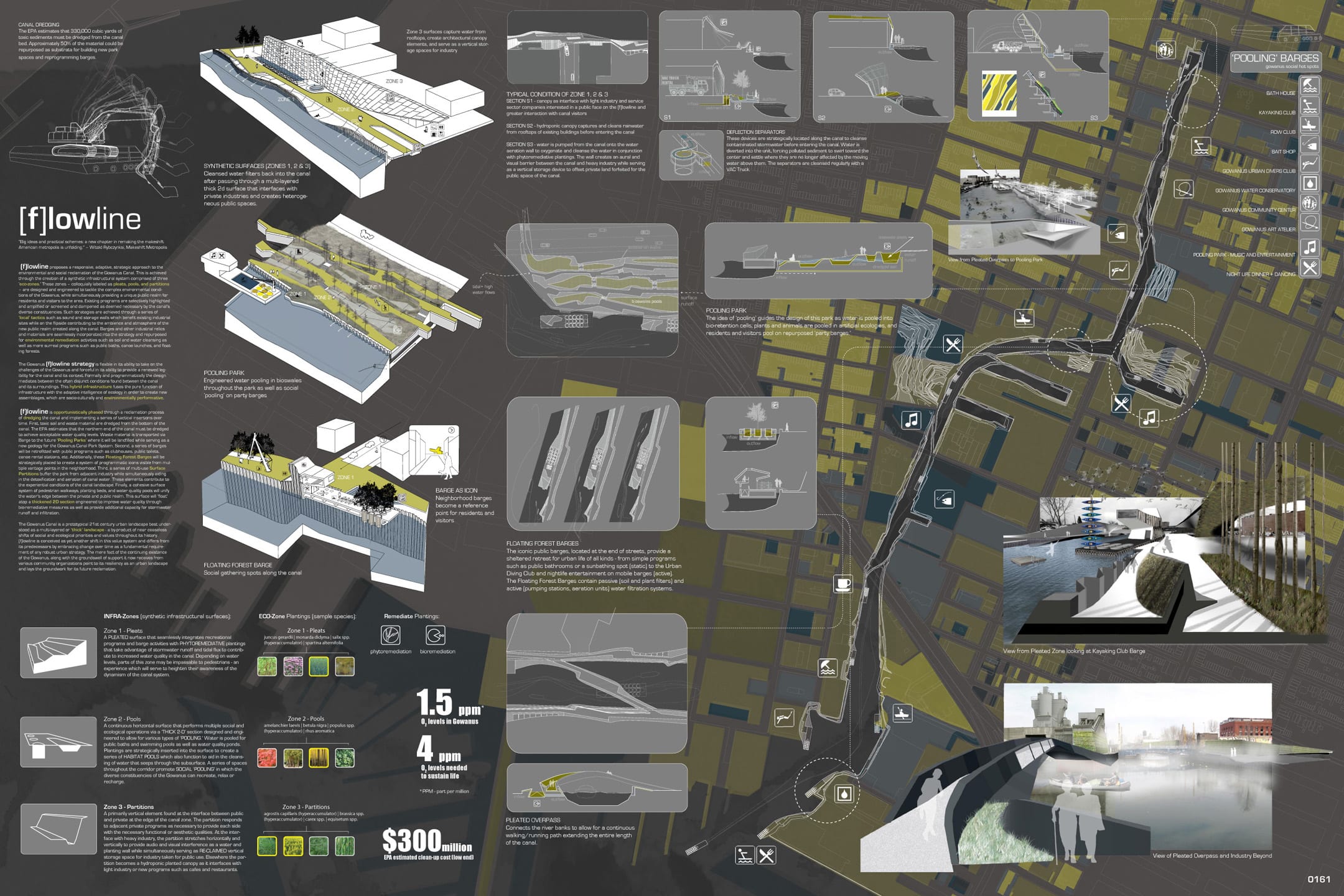

Project: [f]lowline

Team: Aptum/Landscape Intelligence, Switzerland

Members: Gale Fulton, Roger Hubeli, Julie Larsen

The second place team wisely posits a phased design framework that would gradually develop over time as the canal is slowly remediated. Barges would transport waste material generated from canal dredging to create “Pooling Parks,” a system of bioswales creating artificial ecologies long the banks. “Floating Forest Barges” would be stationed along the canal, each holding various social, recreational, and entertainment functions. The jury appreciated the team’s “clever strategy” and “sophisticated, realistic approach to phasing. [It] adapts and responds to changing conditions and offers a vision of the future.”

Honorable Mentions:

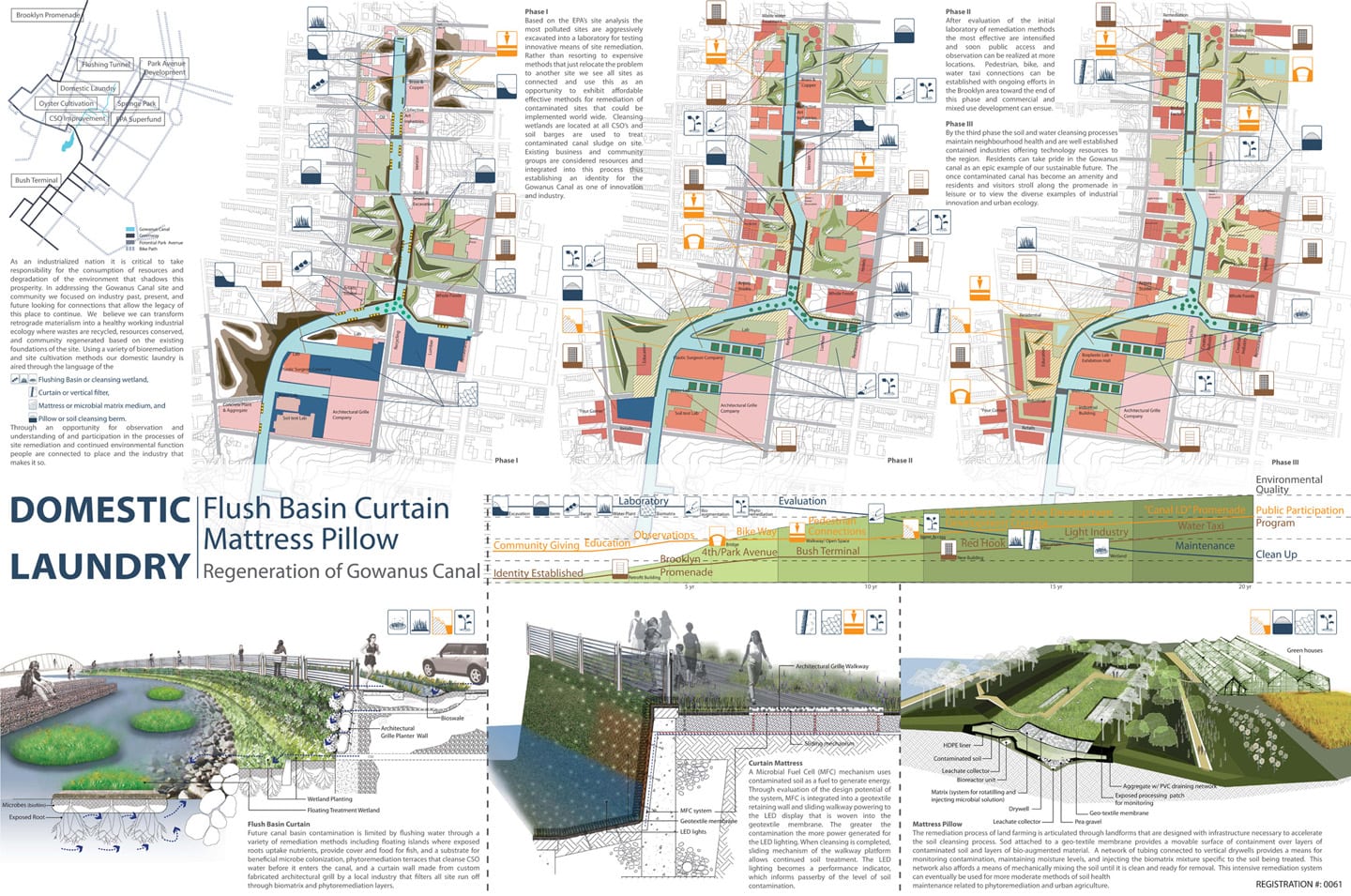

Project: Domestic Laundry: Flush Basin Curtain Mattress Pillow

Team: Agergroup, Boston

Members: Jessica Leete, Claire Ji Kim, Shan Shan Lu, Winnie Lai, and Albert Chung

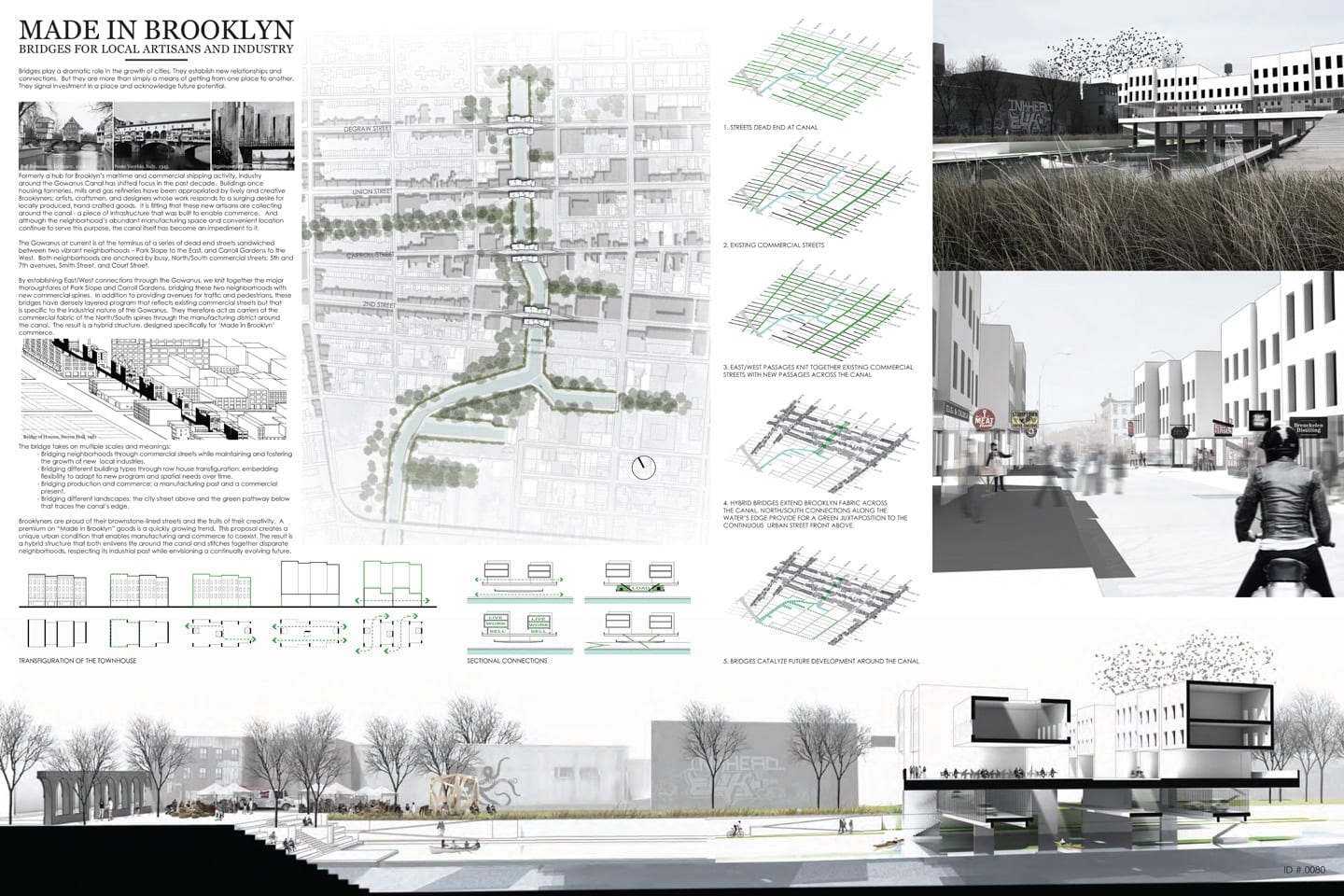

Project: Made in Brooklyn: Bridges For Local Artisans & Industry

Members: Nathan Rich and Miriam Peterson

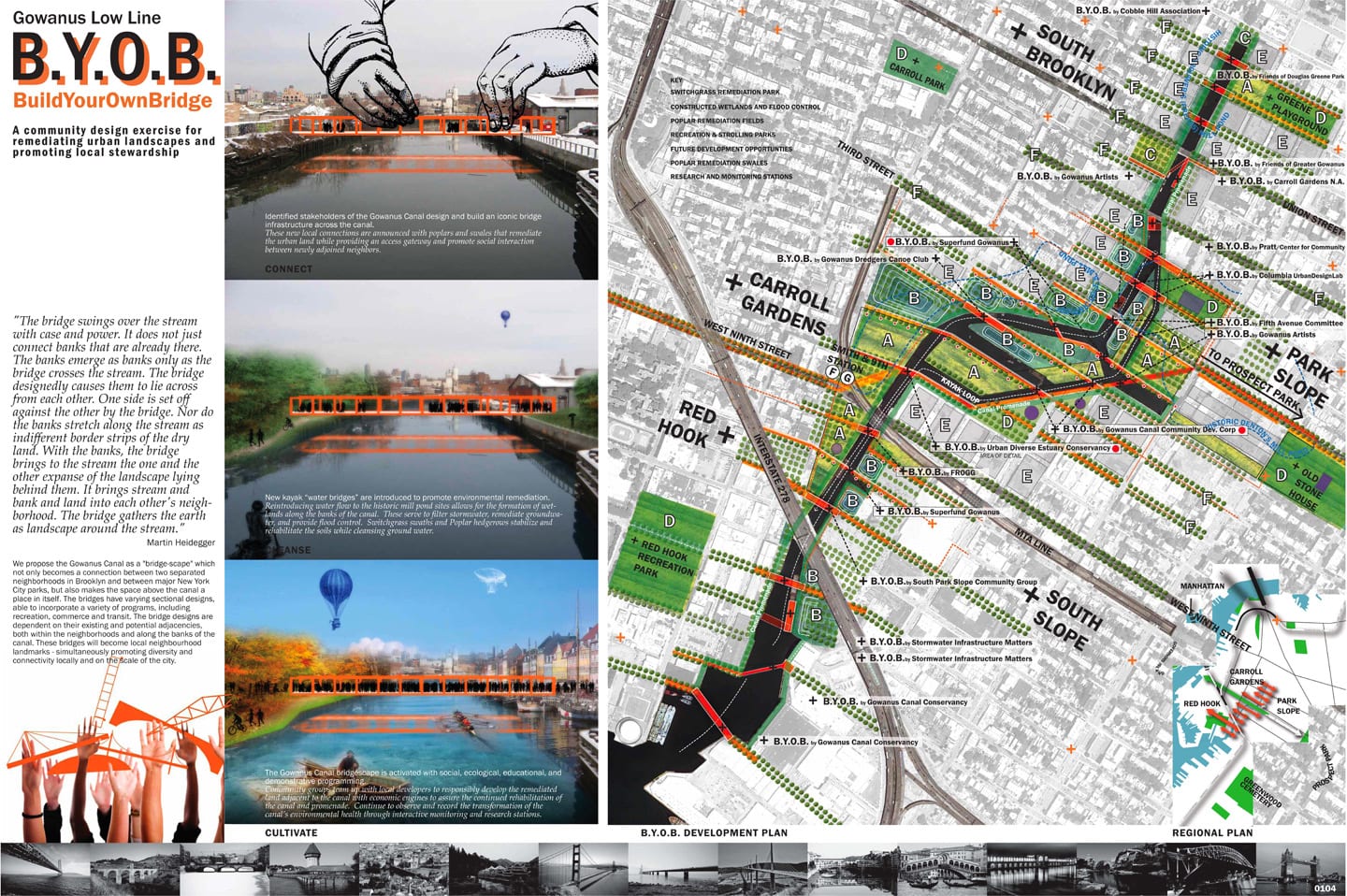

Project: B.Y.O.B. (Build Your Own Bridge)

Team: Austin+Mergold LLC, Philadelphia

Members: Jason Austin, Alex Mergold, Jessica Brown, Sally Reynolds

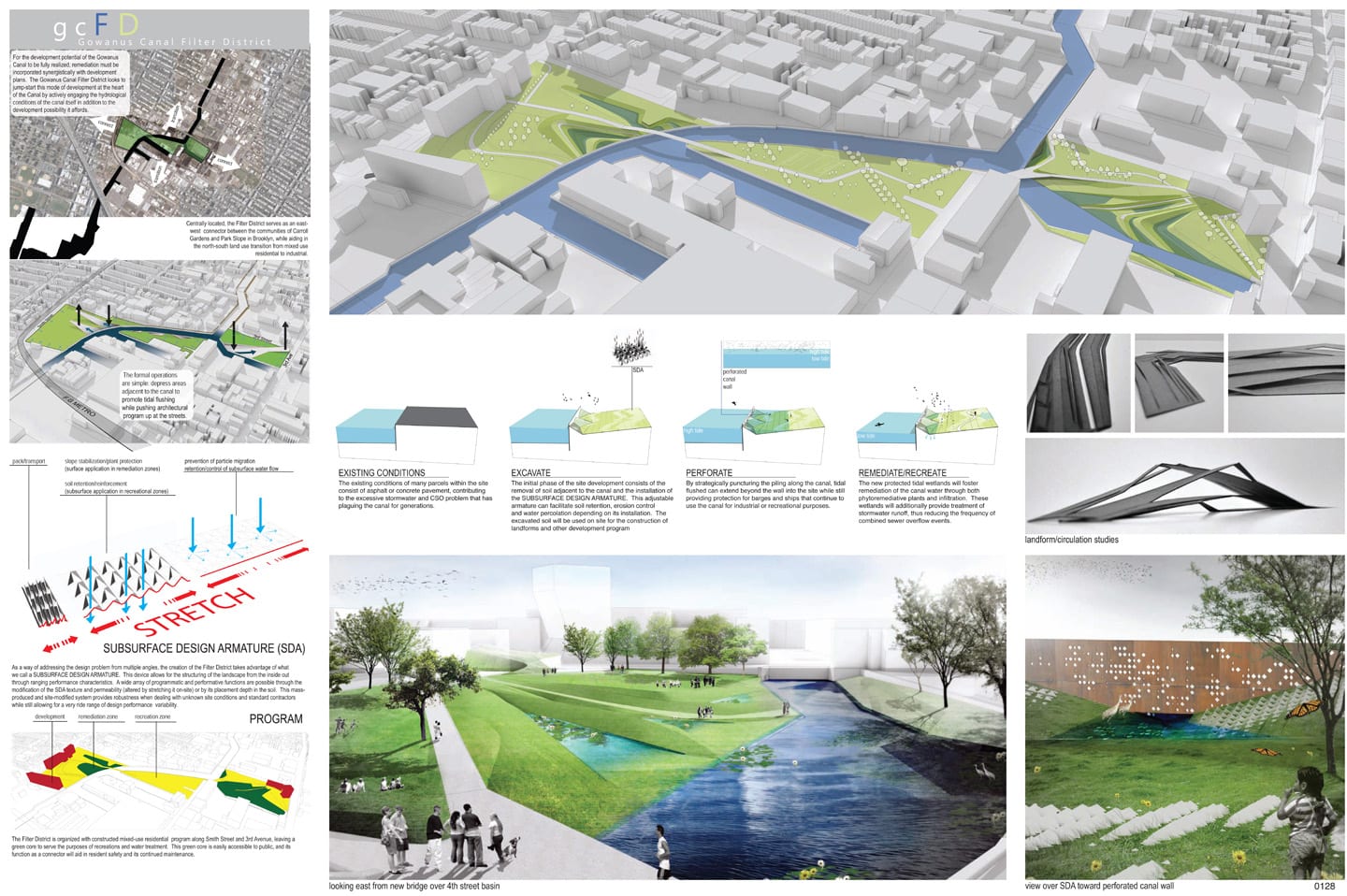

Project: Gowanus Canal Filter District

Team: burkholder|salmons

Members: Sean Burkholder, Dylan Salmons

Taken together, the four honorable mention projects contain a wealth of ideas and strategies. In “Domestic Laundry,” a three-phase clean-up and development plan utilizes a number of well-researched bioremediation techniques for a realistic yet inspiring solution. “Build Your Own Bridge” proposes a “bridge-scape” that helps connect two separated Brooklyn neighborhoods and is set within a network of recreation and remediation parks. “Gowanus Canal Filter District” incorporates natural filtering systems into an attractive park. Meanwhile, “Made in Brooklyn,” the only top choice entry that does not deal explicitly with ecological recovery nevertheless provides an intriguing community development concept: bridges lined with commercial, industrial, and residential functions would help catalyze urban development along the canal and better connect the adjacent neighborhoods.

The first Gowanus Lowline competition rightfully deserves a place in the ongoing discourse surrounding the postindustrial landscape. The most successful entries present truly innovative and exciting ideas as to how to better integrate ecological remediation with the development of a livable, working community. As local and national groups and organizations continue to look at the future of the Gowanus Canal, one can only hope that ideas are culled from the winners and runners up of this valuable competition.

The winning submissions from Gowanus by Design’s inaugural competition Gowanus Lowline: Connections, along with the four honorable mentions, 20 thought provoking “idea leaders” and three winning student teams from the Brooklyn School for Collaborative studies will be on display at the SET Gallery, 287 Third Avenue, Brooklyn for two weeks in September. The show’s opening night is Thursday, September 15, from 6:00 to 9:00 pm.