by Stanley Collyer

The U.S. government funding design competitions abroad? Especially when it has almost been absent in supporting such programs at home? It was not too long ago that the U.S. Congress passed a law stating that no federal funds could be used to fund U. S. international expo pavilions, let alone competitions to determine their design. So those who are wondering that our federal government is spending tax dollars on foreign soil to promote good design should know that its funding for for the Place Lalla Yeddouna redevelopment competition in Fez, Morocco was mainly the result of an economic redevelopment grant from the U.S. Government, and that the competition was only a peripheral add-on.

By its very nature, this competition was not the type of project to attract star architects. While the competition concentrated on upgrading a dilapidated neighborhood where a number of structures are to be replaced, this project was more about giving a boost to local economic development than it was about visuals. Here the existing housing stock, built primarily of masonry, went a long way in determining the parameters of the infill program. Moreover, the site has been a UNESCO world heritage site since 1981. So there was little emphasis on the super modern, especially in view of the constraints resulting from the very nature of the site. As a result, the usual cast of star architects was nowhere to be seen. Rodolfo Machado, a juror and frequent participant in foreign competitions, stated that “the usual luminaries were missing, and I didn’t recognize any of the participants.”

The Planning Process

The competition was conducted in the context of an international development program funded by the United States of America, acting through the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC). In accordance with a 2007 agreement, between the United States and the Kingdom of Morocco, the idea of this project is to “stimulate growth by leveraging links between the craft sector, tourism and the Fez Medina’s cultural historic and architectural assets; strengthen the national system for literacy and vocational education (to benefit artisans and the general population); and support the design/construction of historic sites in Medina. The total MCC commitment for the project’s three sites—Place Lalla Yeddouna being one of them—was US$111,87M. The budget for this site, including the cost of the competitions was $30+M. To organize and assist in the coordination of the competition, the sponsor engaged the Berlin-based firm, (phase eins), led by Benjamin Hossbach. Both stages of the competition were conducted anonymously.

The jury was made up of seven architecture experts and six technical experts. The architecture-related experts were:

• Matthias Sauerbruch, Berlin, Germany (Chair)

• Marc Angélil, Zurich, Switzerland

• Meisa Batayneh Maani, Morocco

• Mohamed Habib Begdouri Achkari, Morocco

• Dr. Stefano Bianca, Geneva, Switzerland

• David Chipperfield, London, U.K.*

• Rodolfo Machado, Boston, USA

With the exception of Richard Gaynor of the Millennium Challenge Corporation (Washington, DC), the expert jurors were mostly local:

Youssef El Mrabet, Mohamed Hassani Ameziane (Architect), Mohammed Msellek, Fouad Serrhini and Abdelkader Nadri (Architect).

•David Chipperfield was only present for the first stage of the proceedings.

The Judging Process

Conducted in two stages, the discussion focussed on four entries in the final phase of adjudication. According to the jury report, “expert jurors and Institutional representatives” remarked on the on the “variety and inventiveness of the submitted proposals and acknowledged that the competition had achieved its intended goals.” Together with the other jurors they attested to the general depth of investigation and the remarkable quality of the presentations, particularly in light of the relatively short time between the first and second phase of the competition.

The key issues which informed the final decision were the successful integration of a new intervention into the organic fabric of the city, the exploration of the site as a location for contemporary activity, the buildability of the proposals and the apparent professionalism of the team. After much discussion, the jury agreed on the following ranking:

1st Prize (US$55,000)

Mossessian & partners, London/UK

with Yassir Khalil Studio, Casablanca/Morocco

2nd prize (US$40,000)

Ferretti-Marcelloni, Rome/Italy

with Bahia Nouh, Fez/Morocco

3rd prize (US$25,000)

Moxon Architects, London/UK

with Aime Kakon, Casablanca/Morocco

The other finalists were:

Giorgio Ciarallo, Milano, Italy

with Emiliano Bugatti, Istanbul/Turkey and Cabinet Hadmi, Safi/Morocco

hanse unit, Hamburg/Germany

with Zine El Abidine Lasouini, Fez/Morocco

kolb hader architekten, Vienna/Austria

with Kubik Studio, Meknes/Morocco

Bureau E.A.S.T., Los Angeles/USA and Fez/Morocco

with Atelier3AM, Toronto/Canada and Hashim Sarkis Studio, Beirut/Lebanon

By its very nature, this competition was not the type of project to attract star architects. While the competition concentrated on upgrading a dilapidated neighborhood where a number of structures are to be replaced, this project was more about giving a boost to local economic development than it was about visuals. Here the existing housing stock, built primarily of masonry, went a long way in determining the parameters of the infill program. Moreover, the site has been a UNESCO world heritage site since 1981. So there was little emphasis on the super modern, especially in view of the constraints resulting from the very nature of the site. As a result, the usual cast of star architects was nowhere to be seen. Rodolfo Machado, a juror and frequent participant in foreign competitions, stated that “the usual luminaries were missing, and I didn’t recognize any of the participants.”

The Planning Process

The competition was conducted in the context of an international development program funded by the United States of America, acting through the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC). In accordance with a 2007 agreement, between the United States and the Kingdom of Morocco, the idea of this project is to “stimulate growth by leveraging links between the craft sector, tourism and the Fez Medina’s cultural historic and architectural assets; strengthen the national system for literacy and vocational education (to benefit artisans and the general population); and support the design/construction of historic sites in Medina. The total MCC commitment for the project’s three sites—Place Lalla Yeddouna being one of them—was US$111,87M. The budget for this site, including the cost of the competitions was $30+M. To organize and assist in the coordination of the competition, the sponsor engaged the Berlin-based firm, (phase eins), led by Benjamin Hossbach. Both stages of the competition were conducted anonymously.

The jury was made up of seven architecture experts and six technical experts. The architecture-related experts were:

• Matthias Sauerbruch, Berlin, Germany (Chair)

• Marc Angélil, Zurich, Switzerland

• Meisa Batayneh Maani, Morocco

• Mohamed Habib Begdouri Achkari, Morocco

• Dr. Stefano Bianca, Geneva, Switzerland

• David Chipperfield, London, U.K.*

• Rodolfo Machado, Boston, USA

With the exception of Richard Gaynor of the Millennium Challenge Corporation (Washington, DC), the expert jurors were mostly local:

Youssef El Mrabet, Mohamed Hassani Ameziane (Architect), Mohammed Msellek, Fouad Serrhini and Abdelkader Nadri (Architect).

•David Chipperfield was only present for the first stage of the proceedings.

The Judging Process

Conducted in two stages, the discussion focussed on four entries in the final phase of adjudication. According to the jury report, “expert jurors and Institutional representatives” remarked on the on the “variety and inventiveness of the submitted proposals and acknowledged that the competition had achieved its intended goals.” Together with the other jurors they attested to the general depth of investigation and the remarkable quality of the presentations, particularly in light of the relatively short time between the first and second phase of the competition.

The key issues which informed the final decision were the successful integration of a new intervention into the organic fabric of the city, the exploration of the site as a location for contemporary activity, the buildability of the proposals and the apparent professionalism of the team. After much discussion, the jury agreed on the following ranking:

1st Prize (US$55,000)

Mossessian & partners, London/UK

with Yassir Khalil Studio, Casablanca/Morocco

2nd prize (US$40,000)

Ferretti-Marcelloni, Rome/Italy

with Bahia Nouh, Fez/Morocco

3rd prize (US$25,000)

Moxon Architects, London/UK

with Aime Kakon, Casablanca/Morocco

The other finalists were:

Giorgio Ciarallo, Milano, Italy

with Emiliano Bugatti, Istanbul/Turkey and Cabinet Hadmi, Safi/Morocco

hanse unit, Hamburg/Germany

with Zine El Abidine Lasouini, Fez/Morocco

kolb hader architekten, Vienna/Austria

with Kubik Studio, Meknes/Morocco

Bureau E.A.S.T., Los Angeles/USA and Fez/Morocco

with Atelier3AM, Toronto/Canada and Hashim Sarkis Studio, Beirut/Lebanon

The Winning Designs

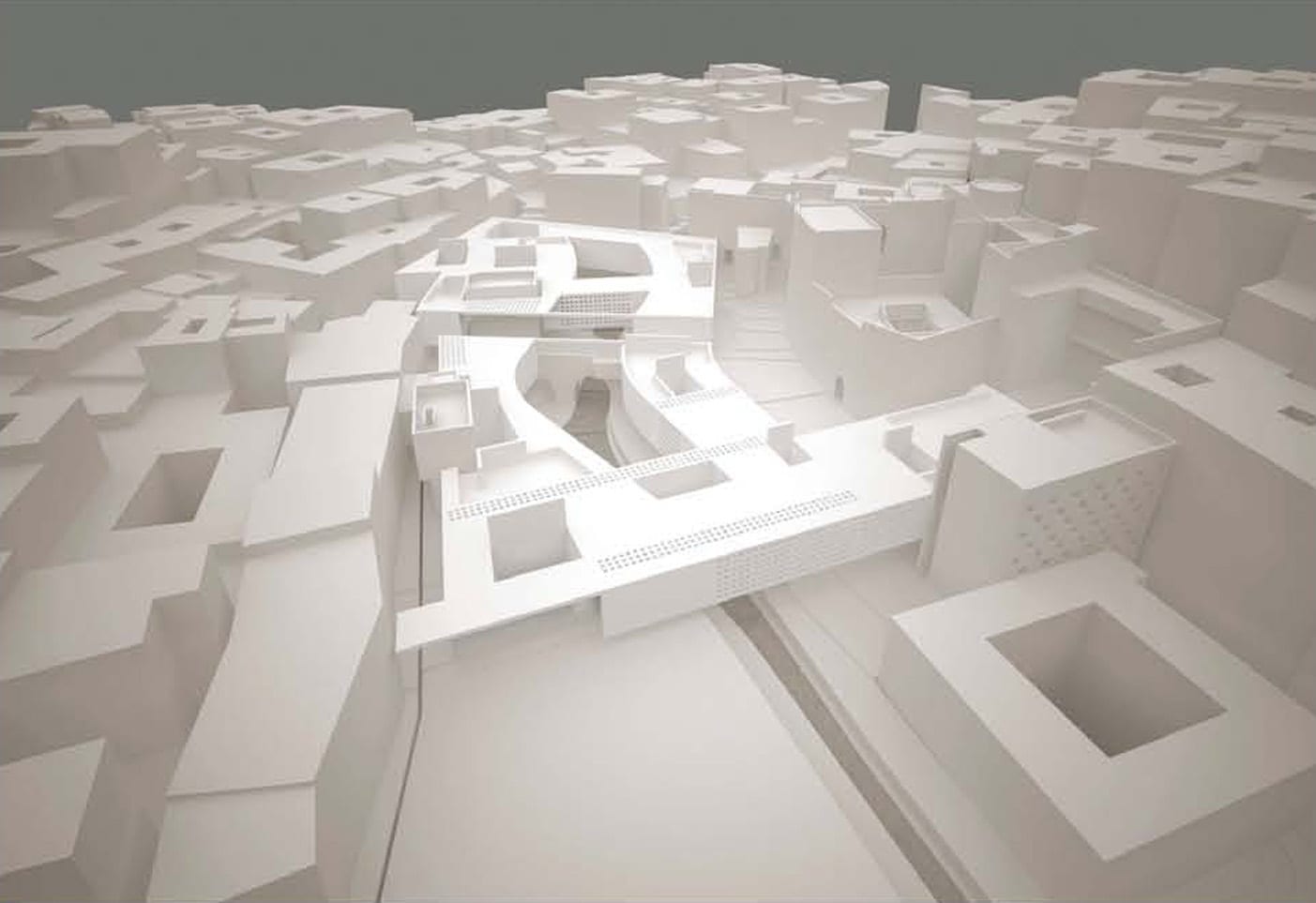

1st prize: Mossessian & Partners, London/UK

|

|

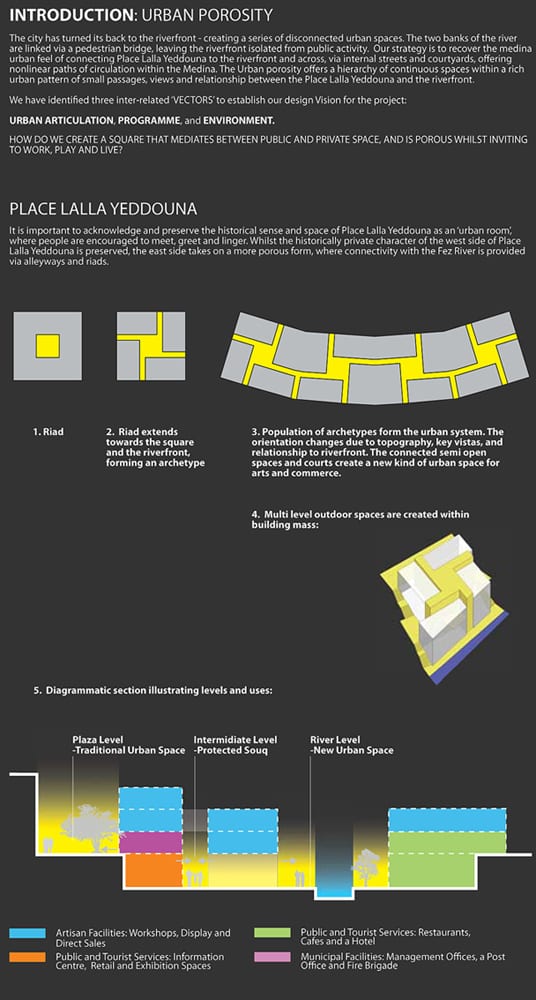

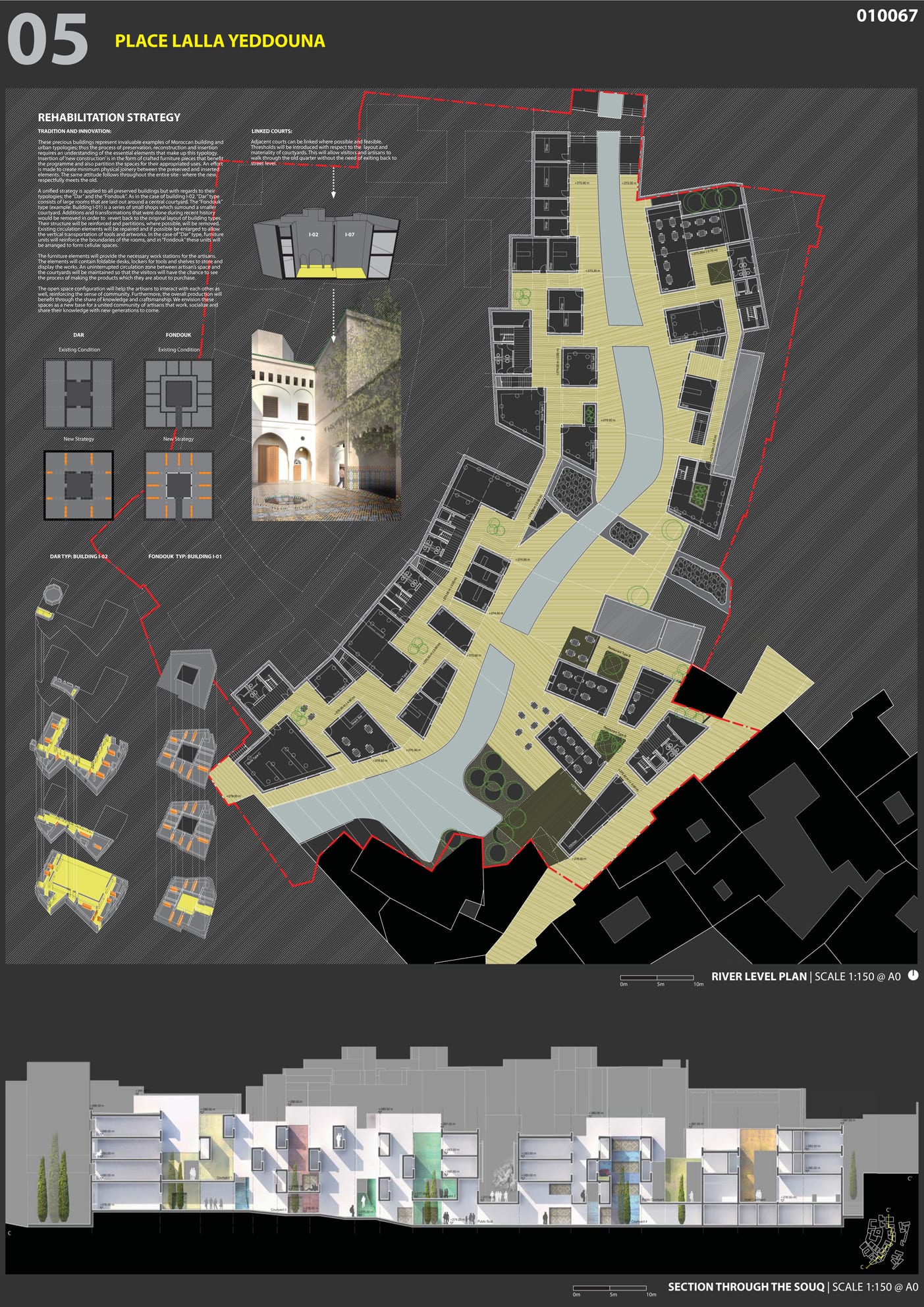

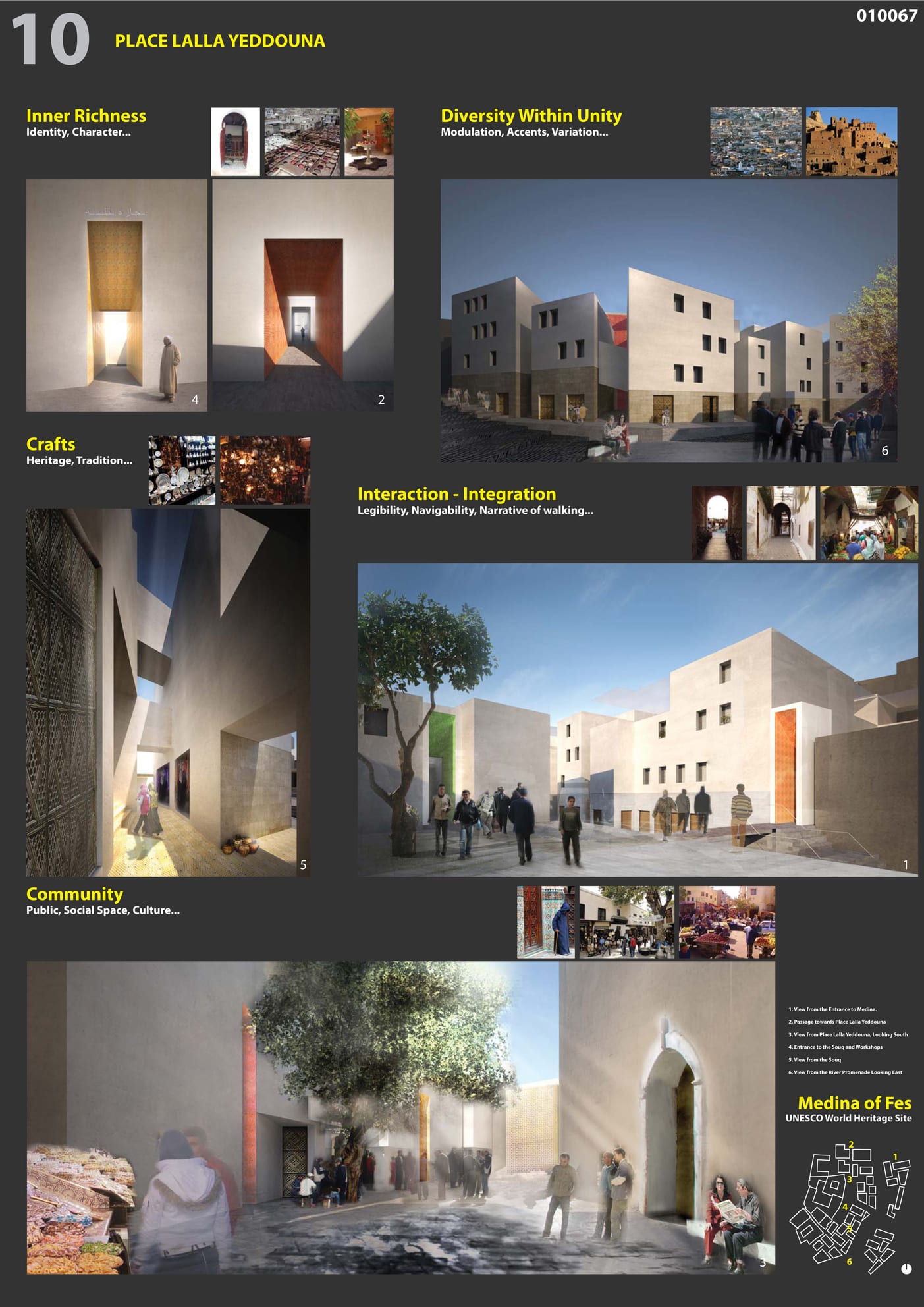

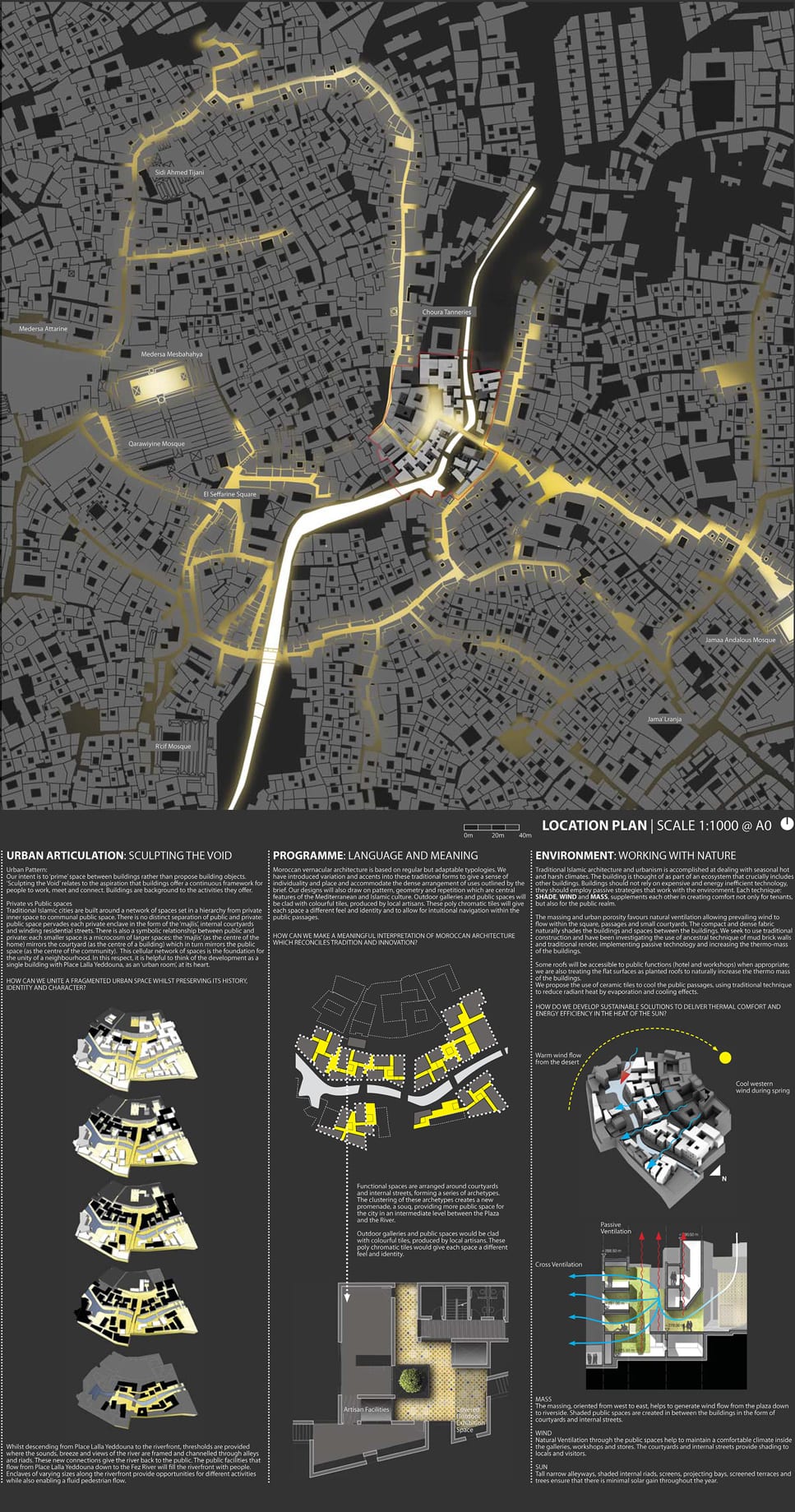

At first glance, the winning entry by Mossessian & Partners might place it in the category of the “traditional footprint.” Upon closer examination, their scheme showed a sophisticated understanding of the program, using a network of paths and passages to link the main site with both the city and the river, “integrating the riverbanks into the traditional street network of the Medina.” Aside from the main access streets from the rest of the city, the internal passages linking small courtyards were not in a continuous linear configuration, thus creating a more interesting flow, and an intimate spatial setting for local residents. The jury also felt that “the simple cuts in the buildings and color-line gateways were a powerful instrument to introduce contemporary spaces into the scheme.

Additionally, the jury agreed on “the supreme feasibility of this complex urban form within the constraints of local building methods and materials.” The materials submitted attested to the high level of professionalism of the team, and the restoration techniques and attention to construction details gave every indication that the project could be built well within time and budget.

Some of the reservations which some members in the jury had concerning the winner probably had more to say about some of those juror’s design agendas than the winner’s response to the program. For instance, some jurors were concerned that the design might be too much of a departure from the “typical” appearance of the “Medina,” noting that it should avoid a possible suggestion of “touristic ‘cuteness.’” Moreover, an excessive use of color in the courtyards, which they considered atypical of the Medina should be avoided in favor of the local palette. This criticism would seem to be exaggerated, as this area is suppose to be, at least in part, a tourist destination where local artisans can sell their wares. As juror Machado noted, “there are plenty of other neighborhoods in Fez where there is quite a bit of color.” On the other hand, the jury’s critique of the same random fenestration proposed using the same windows had more validity.

2nd prize: Ferretti-Marcelloni, Rome/Italy

|

Authors: Laura Valeria Ferretti, Maurizio Marcelloni, Valeria Botti, Sveva Brunetti, Filippo De Dominicis, Benedetta Di Donato In collaboration with: Bahia Nouh, Fez/Morocco Author: Bahia Nouh Freelance collaborators Matthieu Gabay, Alessandra Ienca, Valeria Leoni, Davide Palmacci, Lorenzo Senni Consulting engineers Landscape Architecture: OSA; Environmental Engineer: Gianluca Vanin; Advisor on Restauration: Mutsuko Sato |

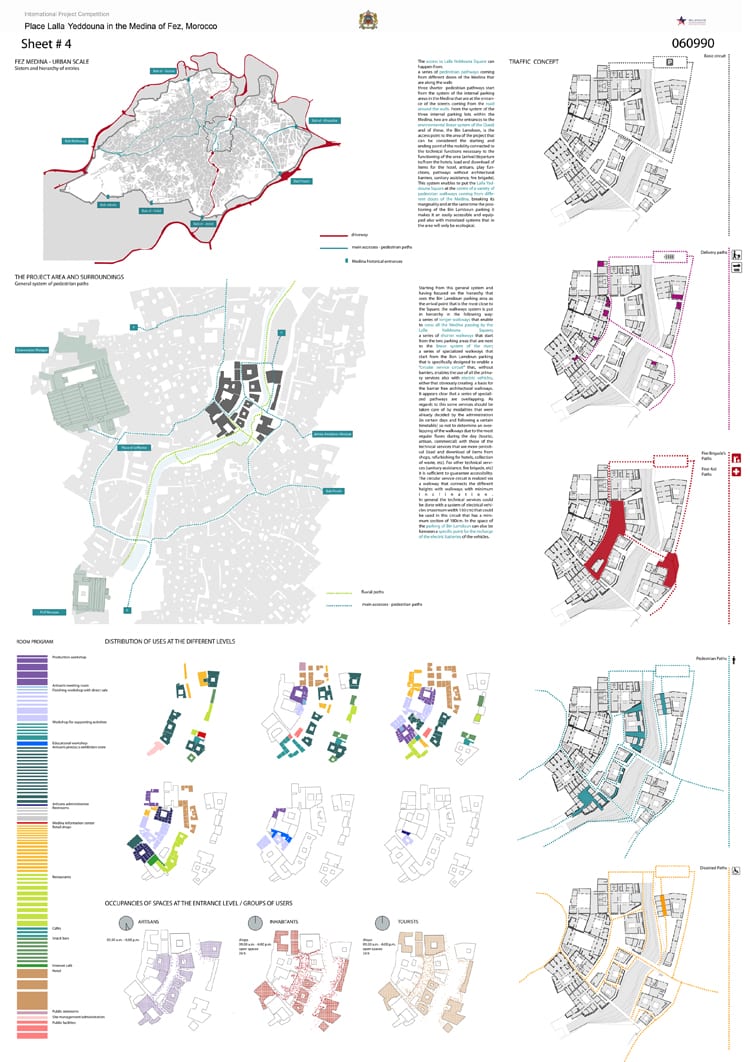

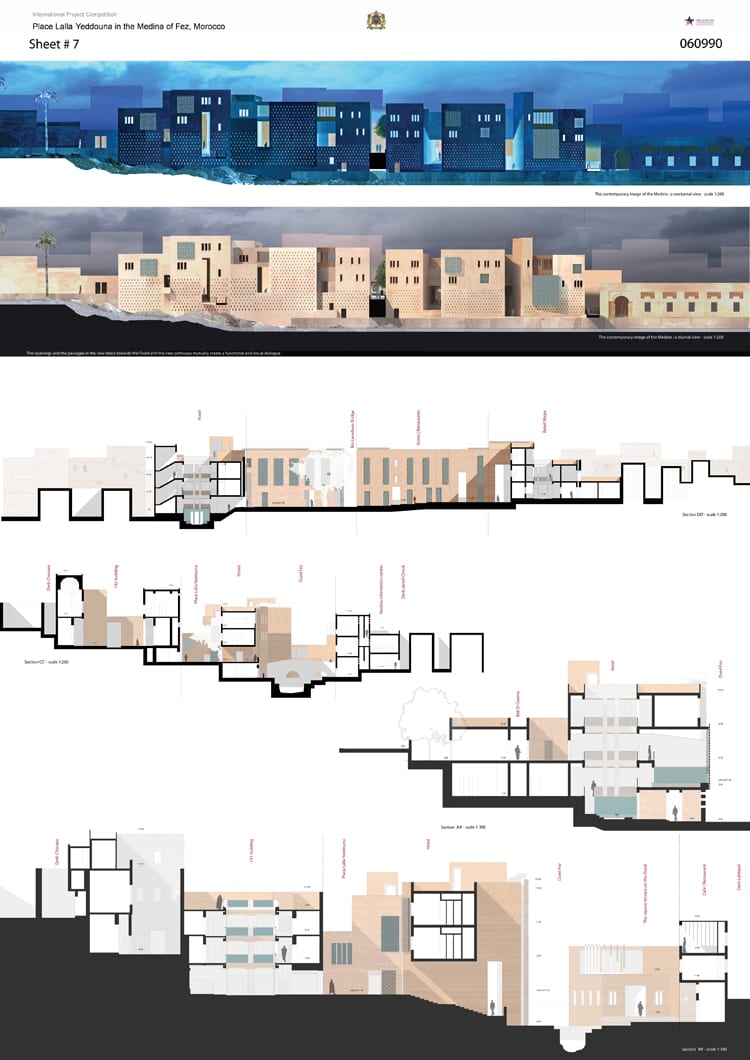

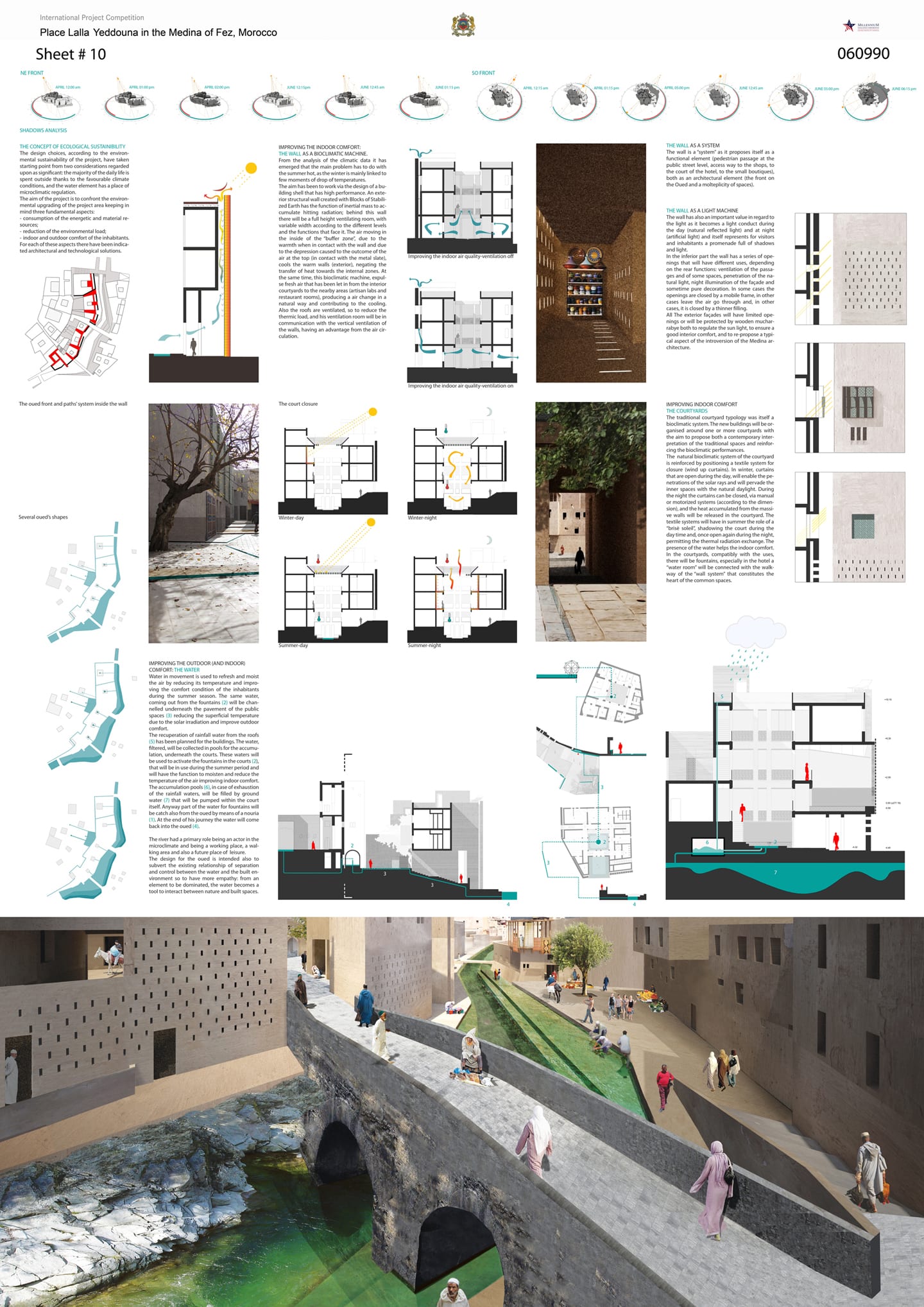

The second-place Ferretti-Marcelloni entry received high points from the jury for its “good volumetric integration into the historic urban fabric, the clever use of existing site opportunities and the implementation of a contemporary language that is based on local typologies and materials. Using a “hard” vertical edge at the river’s edge not only provides the project with a sense of high density; the way in which it is penetrated from the river might suggest a sense of discovery once one is inside those walls and a different level of sophistication in urbanity from the outright winner. There are a number of sustainability features, including the use of fountains to lower the heat factor in the summer and light shafts in the structures, enhancing livability in the interior. When speaking of the project’s architectural expression, the jury hit the nail on the head by describing it as having “a consistent formal language without being monotonous. Here it was not just about upgrading the existing; the architectural language here is North African in massing, but pushing toward the modern in architectural expression.

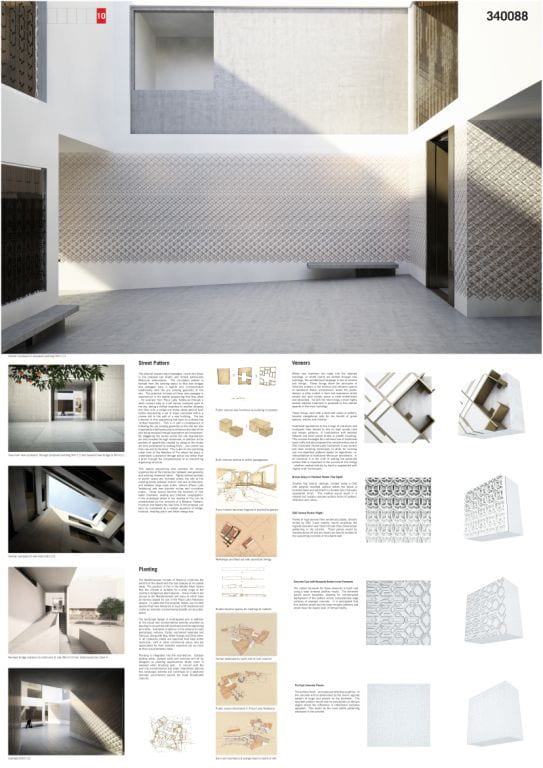

3rd prize: Moxon Architects, London/UK

|

|

Moxon Architects was praised for its examination of the role of historic preservation within contemporary culture. They emphasized ‘subtleness’ as a principle posture in relating the new and the old, with a focus on the craft of intervention. “Existing buildings are retained where possible and new building fit preexisting footprints — in this way the scheme is above all else one of conscientious repair to the precious fabric of the medina.” As with the winner, the care with which the organization of the circulation pattern into public, semipublic, and semiprivate was in the forefront. On the other hand, the jury found that “certain design propositions at the detail level appear to be out of context and partially overdone in terms of the composition of elements and their ‘cleanness’ or ‘coolness’ in style. Overall, the proposal offered “an extremely interesting solution to the competition brief and presents a highly valuable strategy for addressing the transformation of historic urban fabric.

Round 2 Finalist: Bureau E.A.S.T., Los Angeles/USA and Fez/Morocco

|

Authors: Takako Tajima, Zineb Medaghri Alaoui |

Jury Comments:

The jury interpreted the project as a very valuable attempt to establish a plausible symbiosis of the new and the existing. On an urban level the reflection of the basic site topography as the generating factor in the development of a sophisticated internal space is as interesting as the proposed coexistence of two public spaces as different as Place Lalla Yeddouna and the contemporary “soft-edge” river park. The jury also much appreciated the attempt to find principles of social intervention in a very demanding context. One jury member remarked in the proceedings that “Fez was not a plan but a history” and this project was seen by some as the one most suited to continue in this way of thinking. However, there were also serious misgivings about the architectural resolution of the scheme. The plans seemed generally underdeveloped, the design of the hotel too diagrammatic. For those in the jury who thought the establishment of principles of development to be of higher importance than final form the project still made a very strong contribution. However, given the time constraints and the “real” nature of the undertaking it did not convince a majority. The scheme was voted into the shortlist but finally wasn’t awarded a prize. It did, however, make an original and wellconsidered contribution to the discussion around this type of intervention in general and Place Lalla Yeddouna in particular, that was much appreciated.

Round 1 Finalist: Kolb Hader Architekten,Vienna/Austria

|

Author: Christian Hader |

Jury Comments:

The jury values the ambitious urban strategy of the project. It is based on a single, large architectural intervention, in a way, a new type of mega structure, being no object building. In fact, it is a segment of an architectural tissue raised above the ground and objectified – turned into a mega structure. As such, it contains many courtyards and intimate streets. In this transformation lies the novelty of this project. The project is clear and rigorous, offering a very good urban elevation towards the arrival from the parking to the north as well as a very interesting small-scale series of elevations to the Place Lalla Yeddouna itself. The jury appreciated, in particular, the roof landscape with its potential for public use. However, regarding feasibility the project carries too many doubts, which led the jury to the decision not to award a prize to the project.

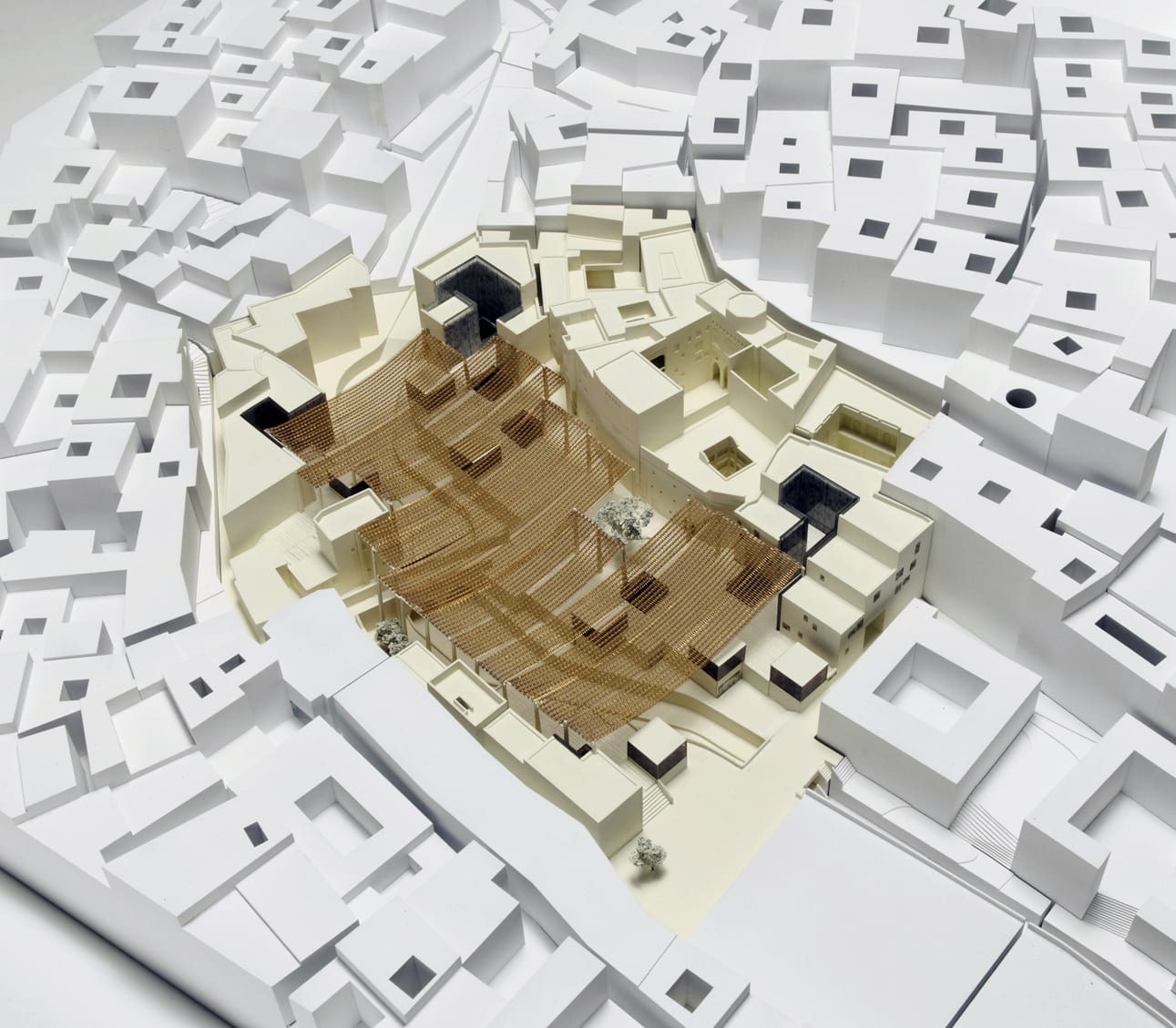

Round 1 Finalist: Hanse Unit, Hamburg/Germany

|

Authors: Carsten Venus, Ole Flemming, Rüdiger Ebel, Bert Bücking, Volker Halbach, Patrick Ostrop |

Jury comments:

The quality of the scheme much depends on the idea of a large canopy connecting all the new buildings into a continuous roof-top promenade for tourists. Morphologically this presents an attractive idea as this large-scale element meets a contemporary mode of use but also isolates and frames one urban typical situation within this 1000-year-old city. However, the jury is in doubt whether the fundamental idea will work. To “reroute” some of the activities and the associated pedestrian traffic from the ground onto the roof might weaken the typical street life and introduce a relationship to the city that –at least some of the local jurors- find alien. Secondly the success of the idea will largely also depend of the quality of the roof itself. It is shown on the drawings as a light veil but the authors fail to explain how they want to achieve this impression in the face of their own ambition to make this roof the carrier of some major technological components. Once wind and seismic requirements have been considered as well it might end up considerably more solid and hence much more present in a way that could not really be imagined to be in keeping with the world heritage of the site. Neither the relatively predictable floor plans nor the dutiful quotation of a collection of local materials reassured the jury that this might be a scheme that might excel beyond the one –admittedly at first sight seductive- scheme of the rooftop promenade. The idea of a decorative ‘Garden of Eden” that cannot be entered 364 days a year located in the middle of a busy artisan’s district where access to the water is essential seems to reinforce the reading of this site predominantly from a tourist’s perspective.

Round 1 Finalist: Giorgio Ciarallo, Rho/Italy

|

Authors: Giorgio Ciarallo, Marco Spada Compagnoni Marefoschi, Paolo Spada Compagnoni Marefoschi |

Jury Comments:

The jury appreciated the ambition of the project to create a new urban space as a very positive strategy. Furthermore, the jury appreciated the relatively high level of resolution of the proposal and the desire to engage and interpret traditional construction techniques, materials and architectural language. However it criticized the scheme for being rhetorical. The jury remained unconvinced of the new public space given the compromised nature of its ground surface. The enclosure of the river and the surrounding embankments is actually designed as a space to look at rather than to be in. In turn, the public space that people would actually occupy is reduced to a mere corridor. This was seen to be in fundamental conflict with the architects stated intention to create a Gran-Fondouk and therefore regarded as a major weakness.

Round 1 Finalist: Arquivio Arquitectura, Madrid/Spain

|

Author: Daniel Fraile |

Jury comments:

The jury appreciated the clarity of the scheme, and the bold idea not to rebuild the existing structures and to offer a piazza instead that could serve as a recreation area and a place to meet, reflect and share, also for festivities like a traditional “Saha”. The proposal also offers a generous space on the lower level to be used for commercial activities. A simple grid articulates the space and makes it easy to construct. This is a project that celebrates Fes as the city on the river, with the new piazza interacting with the water on two levels. However, the quality of the scheme fundamentally depends on the realization of the large hanging roofs as they provide essential climate moderation, and give scale as well as spatial definition. Given the available budget and the complexity of its construction this element was called into question even though the jury appreciated the intent to involve local craftsmanship in its production.

Summary

Although some may find this competition lacking as real design challenge, there are some lessons to be learned here. Although architects were not asked to design a mega-structure as part and parcel of this program, the plethora of solutions for urban infill should provide all urban planners with food for thought. Although very site specific, the research and thought given to this infill process might well be emulated by planners in other parts of the world. Based on the results of Place Lalla Yeddouna redevelopment, the road to such solutions can reside in carefully planned and executed design competitions.