by Dan Madryga

Northwestern University is getting a major architectural facelift. Over the past few years, the university has staged several invited design competitions for large-scale building projects on its Chicago and Evanston campuses. A new 152,000 square foot building for the Bienen School of Music and Communication, designed by Goettsch Partners, is currently under construction and slated to open later this year. Meanwhile the 410,000 square foot Kellogg School of Business—for which Toronto firm KPMB beat out Kohn Pedersen Fox, Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill, and Pelli, Clark & Pelli for the commission—is expected to be ready for occupancy in 2016. As large as these projects are, Northwestern’s most recent invited competition dwarves them both in scale, budget, and ambition: a brand new Medical Research Center for the Feinberg School of Medicine.

The new Medical Research Center is a huge undertaking for Northwestern. Once complete it will introduce 1.2 million square feet of state-of-the-art lab space, with which the University expects to attract an additional $150 million a year for medical research, as well as create 2,000 new full-time jobs. Needless to say, the project is at the forefront of the university’s projected master plan.

Of course the architectural evolution of any urban campus necessitates some selective purging of the existing building stock. For the Medical Research Center’s central location on the Chicago campus, this has unfortunately meant the loss of Bertrand Goldberg’s 1975 Prentice Women’s Hospital. This move created no small amount of controversy amongst preservationists and fans of Goldberg’s distinctive, sculptural concrete cloverleaf form. Goldberg was a Chicago architect—a protégé of Mies van der Rohe—who also designed the instantly recognizable twin corncob towers of Marina City. Originally hailed for its innovative engineering and striking form, the Prentice took an innovative approach to organizing medical wards in clusters, thus lending to its distinct form. General reactions have always been mixed: for some it was an iconic work of Brutalism, for others it was simply an eyesore. Either way the hospital was clearly dated by the 21st century standards of functionality, and Northwestern’s development future did not include the Prentice.

Proponents of the Prentice pulled out all the stops to try and save the endangered hospital. Preservationist groups sought to protect it with a Landmark status designation that was ultimately denied. Chicago’s Studio Gang offered up a striking design idea that would save and incorporate the Prentice into the new research center. The efforts even extended to an ideas competition. In 2012, the Chicago Architectural Club organized “Future Prentice” as the timely theme of the annual Chicago Prize Competition. Entrants were challenged to find creative solutions for repurposing the old hospital building, in hopes that thought-provoking design could spark a useful public dialogue about solutions that went beyond full-on preservation or wholesale demolition. In addition to the 71 entries received, the Chicago Architectural Club commissioned designs from ten up-and-coming local architecture firms. Together these 81 ideas were displayed at the Chicago Architecture Foundation’s “Reconsidering an Icon” exhibit in late 2012 and early 2013.

The Future Prentice entries ranged from compelling yet largely grounded adaptive reuse ideas (the first prize entry by Cyril Marsollier and Wallo Villacorta imagines the Prentice’s distinctive concrete shell as a museum presented amongst the boxy volumes of a new research lab facility), to wildly left-field theoretical concepts (the second prize entry by Noel Turgeon and Natalya Egon, where various architectural additions are vertically stacked upon the Prentice to form a “timeline of trends in architecture”). In the end, the competition might have created an interesting dialogue but not with the people who really needed convincing. Given the longstanding plans to demolish the vacant hospital, Northwestern made it clear that all ideas for saving the Prentice would not be seriously reviewed by the University. Like the attempts to enact landmark status, the Future Prentice ideas competition was too little, too late.

Not long after the ideas competition came and went, Northwestern officially released their request for qualifications for the new Medical Research Center, with proposals due in April 2013. The RFQ was sent to 23 architecture firms, six of which were local Chicago firms, and most of which had previous experience in large research and medical projects.

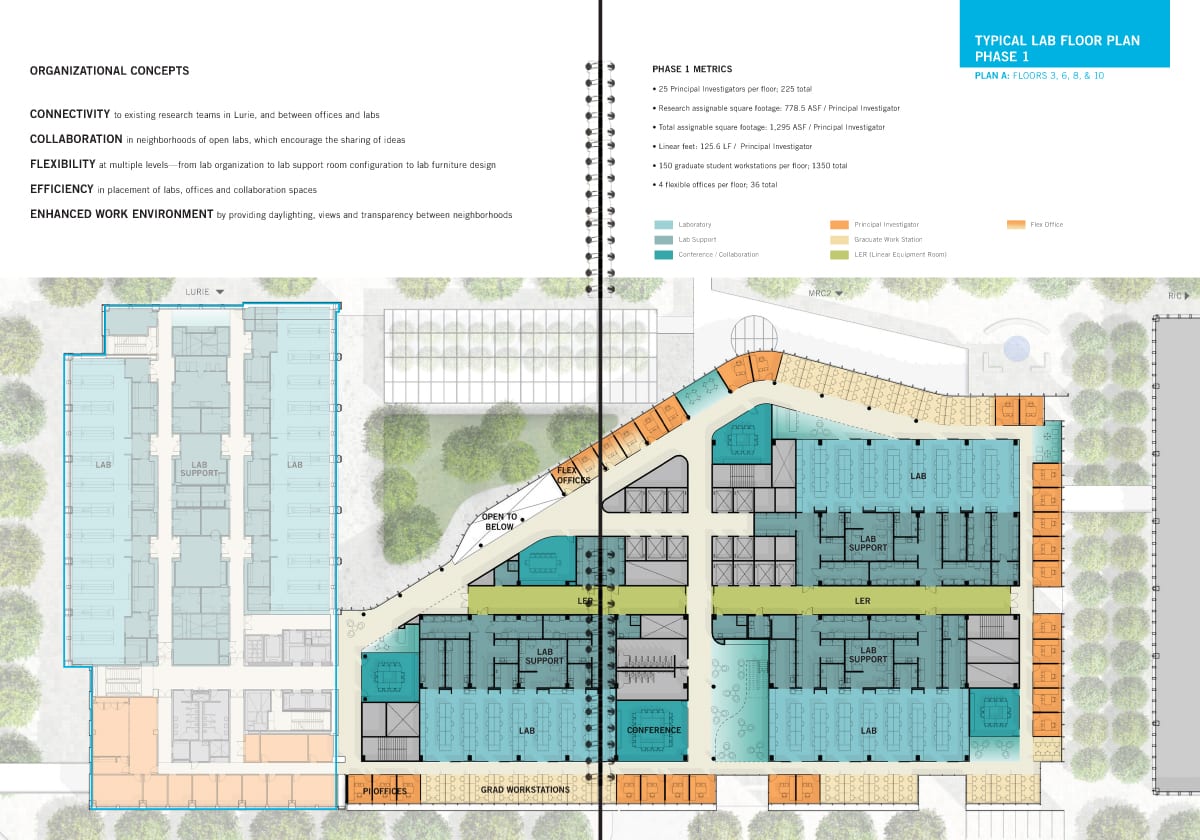

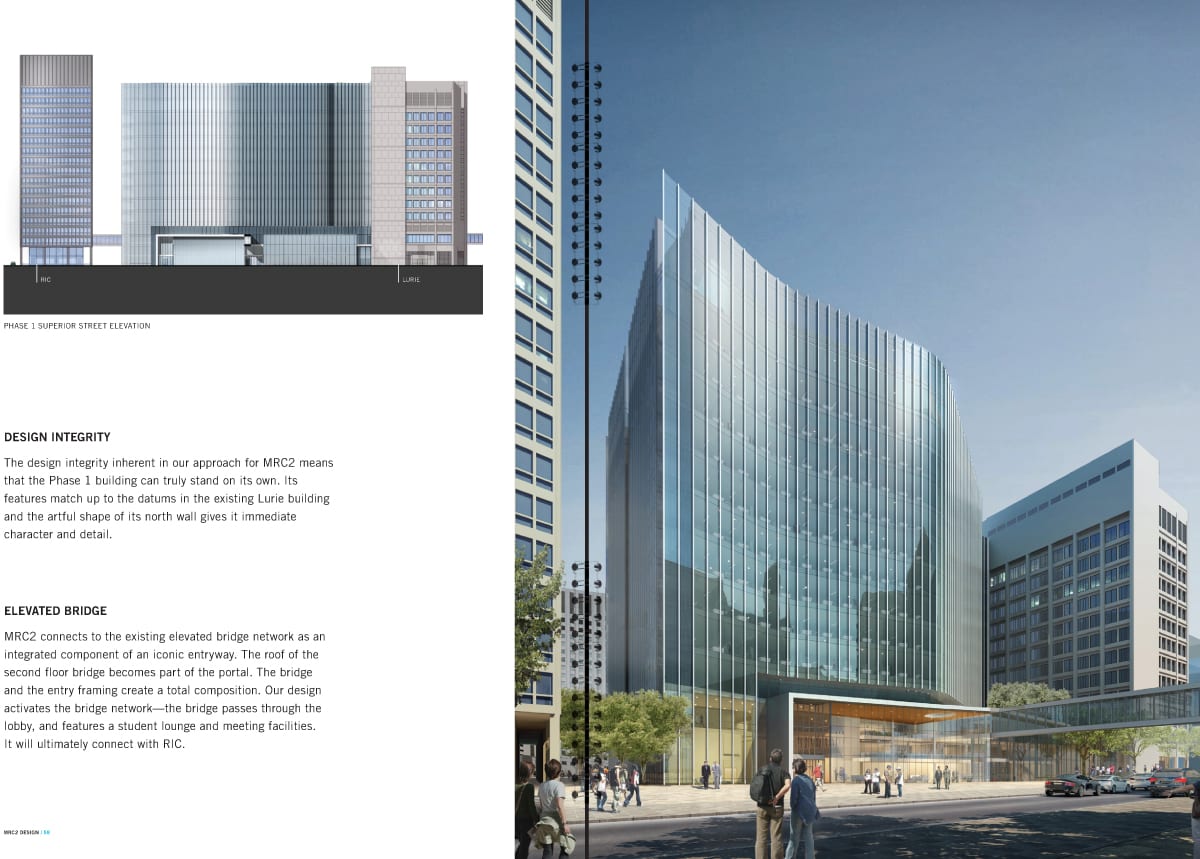

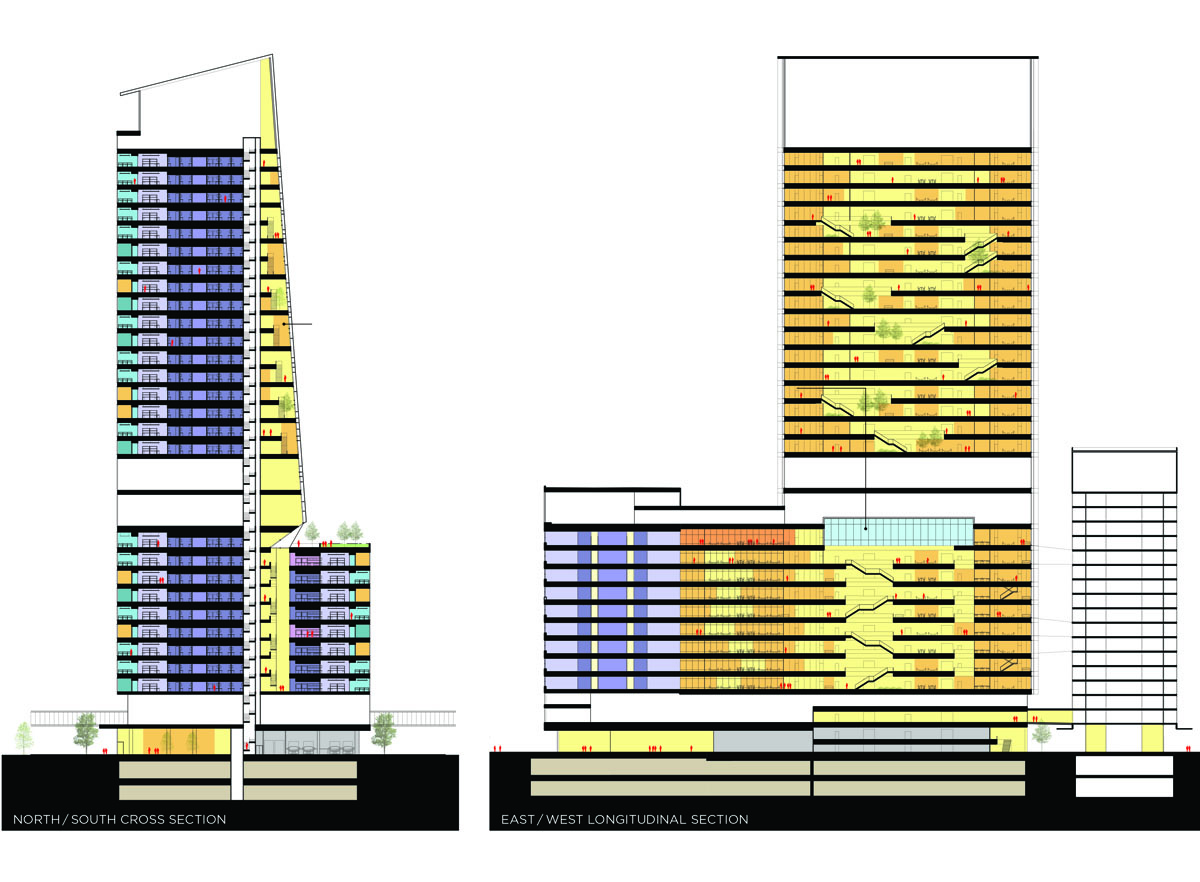

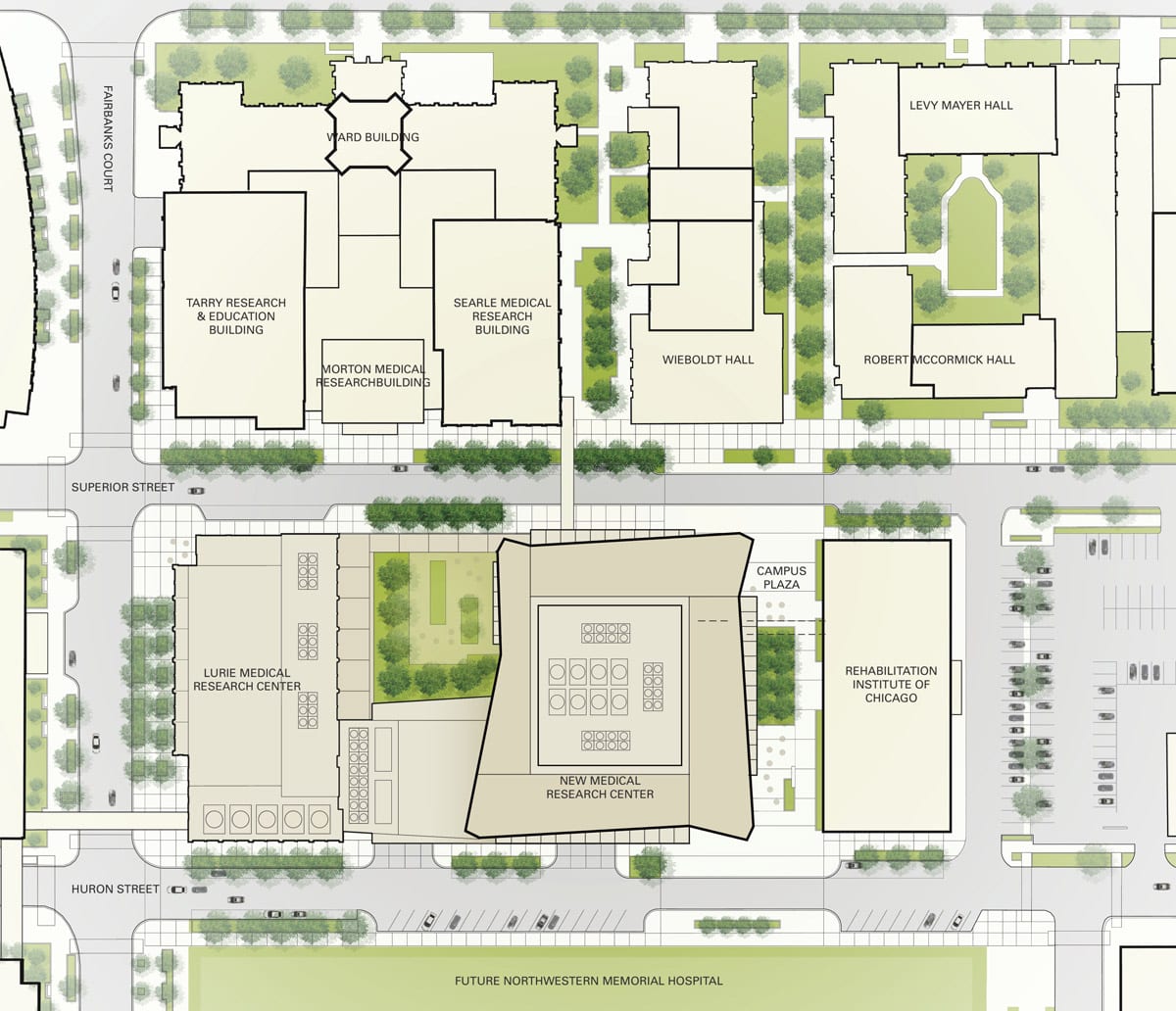

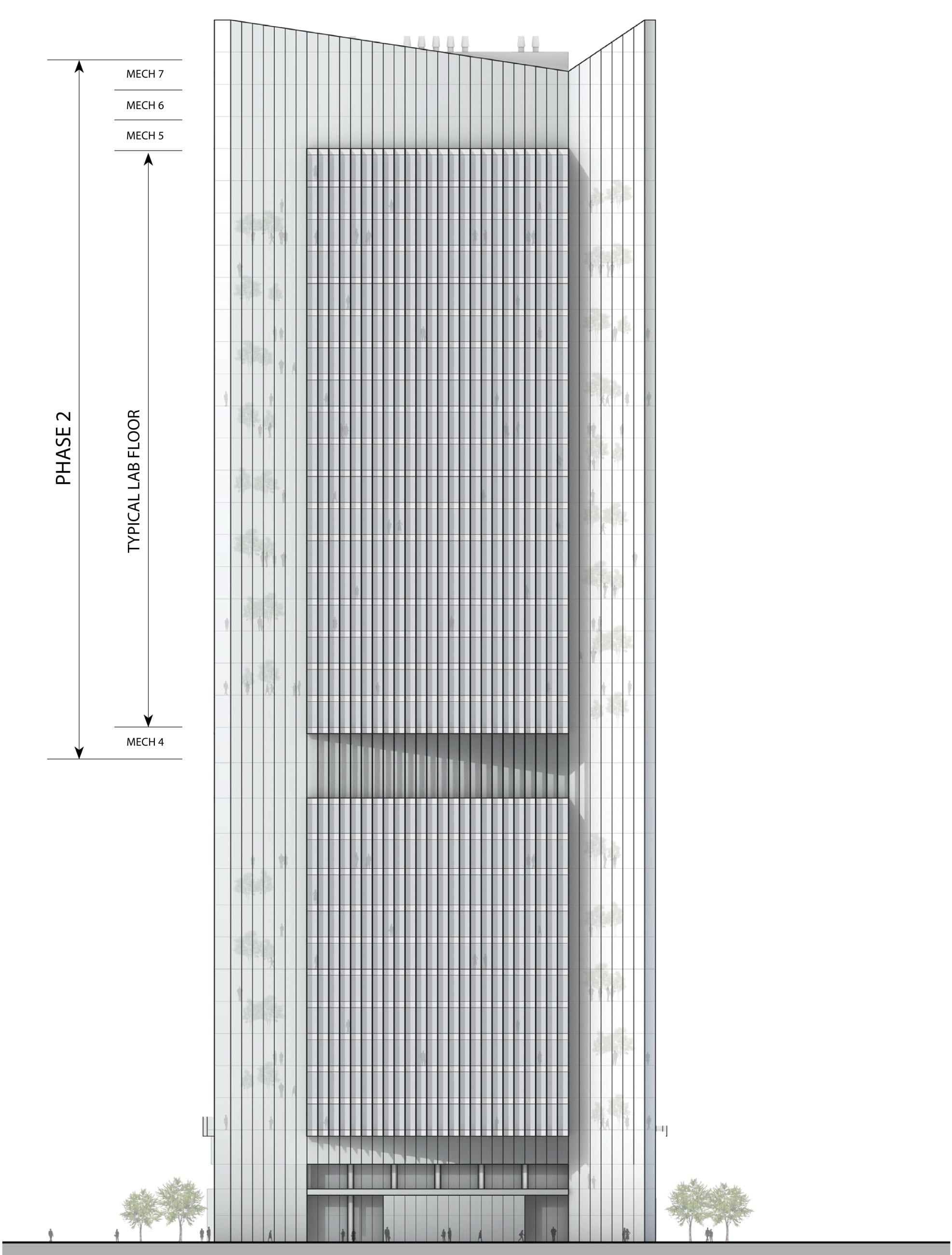

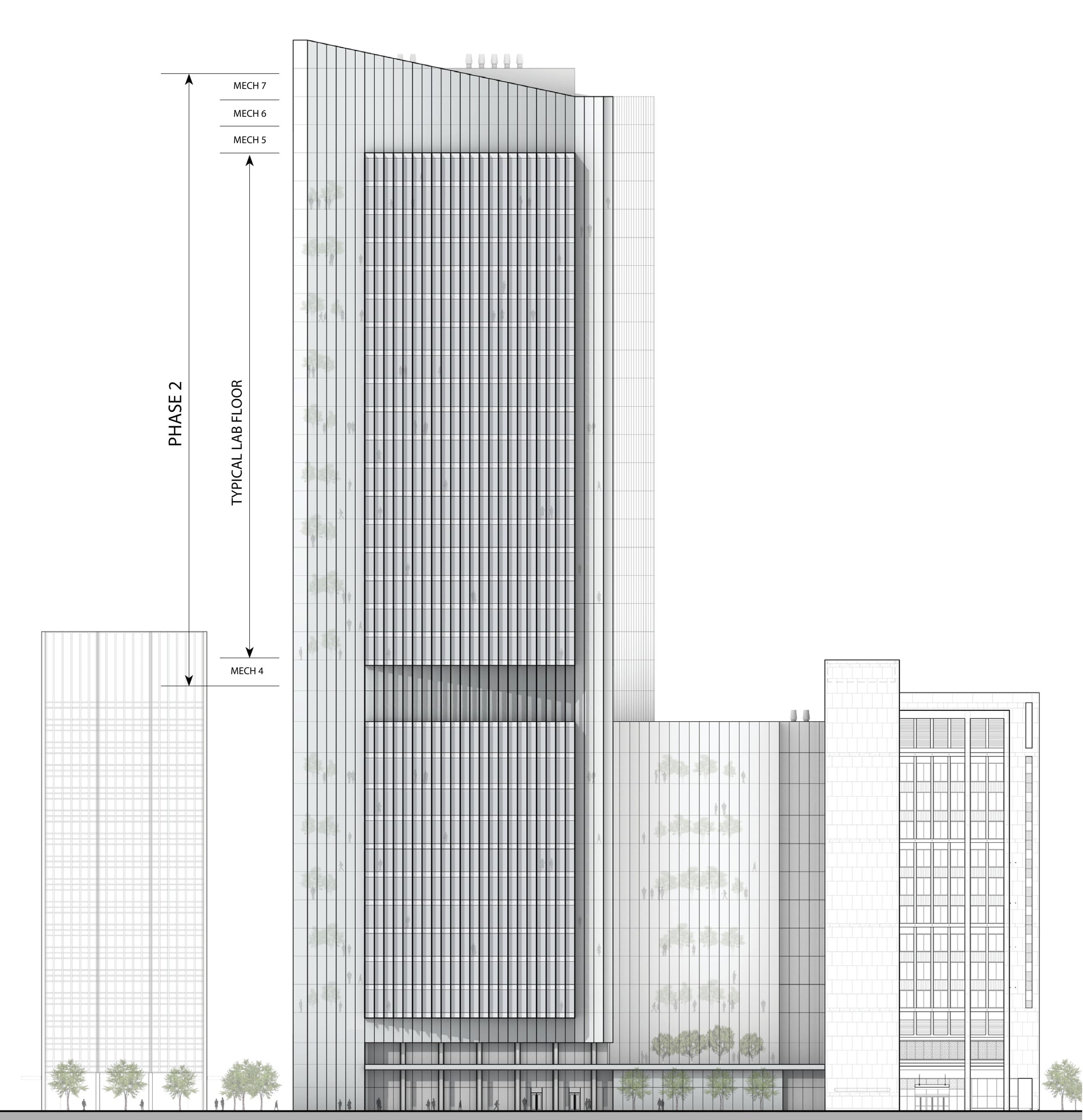

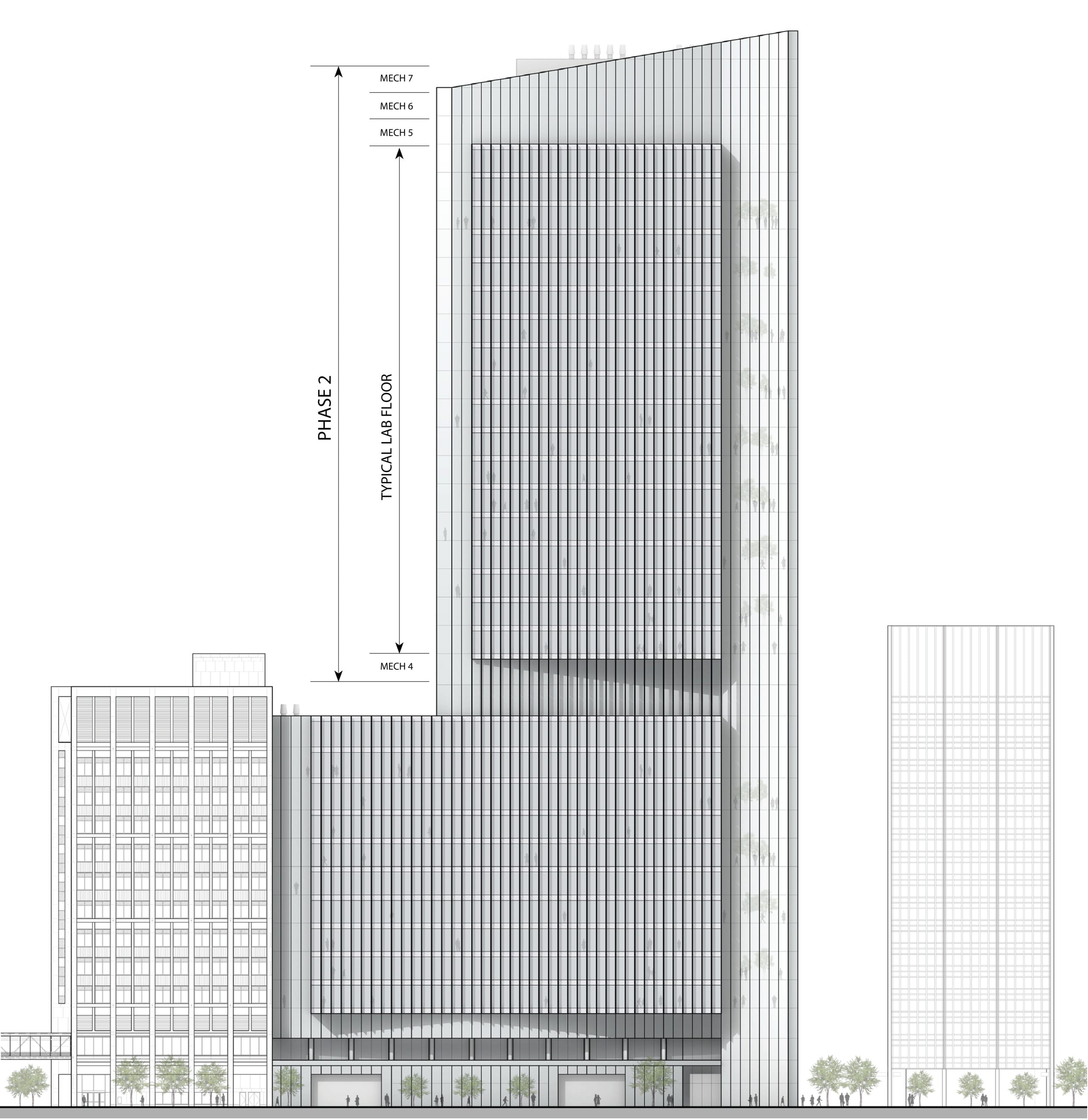

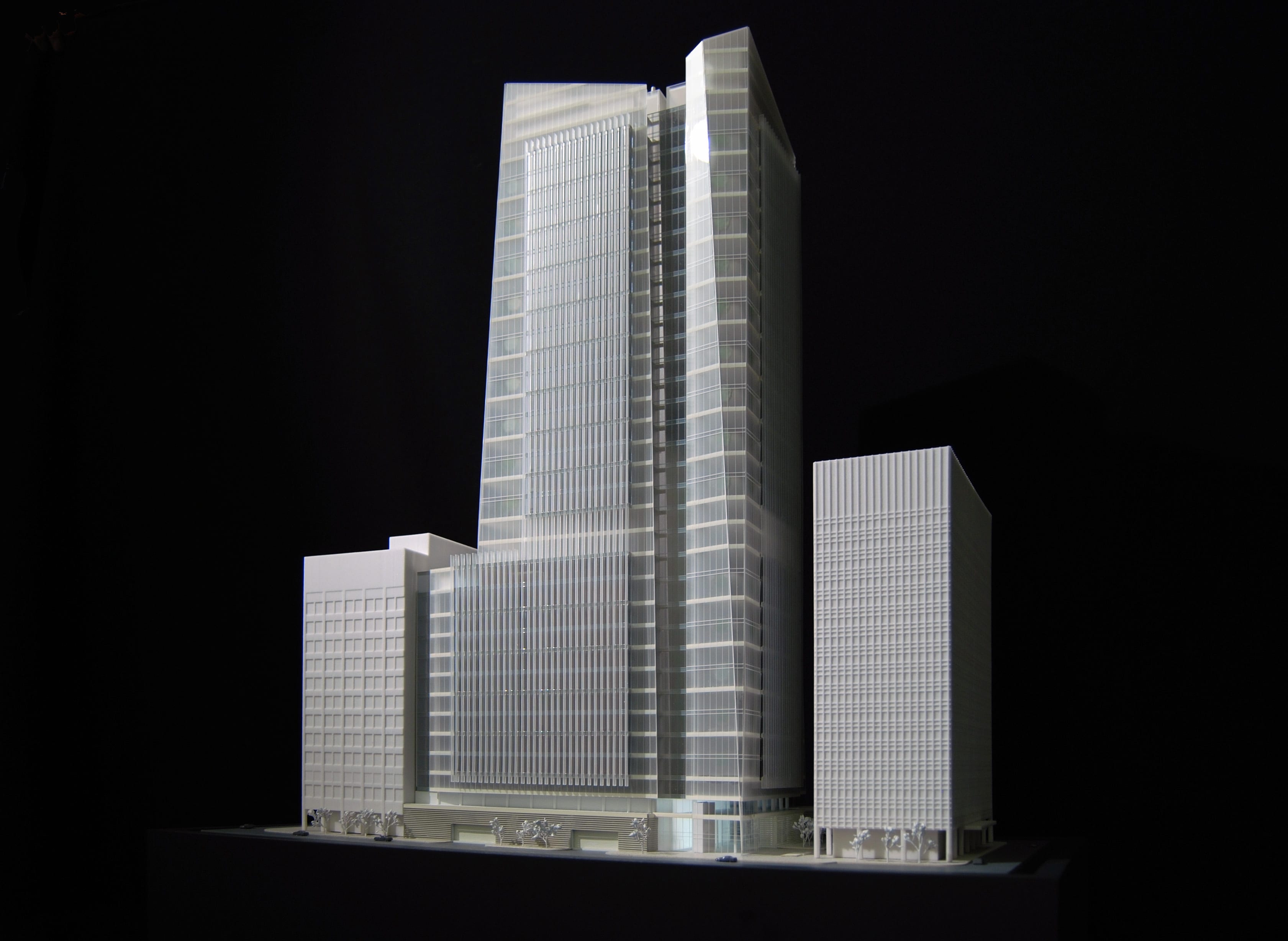

Northwestern’s program called for a research center that would be implemented in two phases. Phase 1 will consist of a 600,000 square foot, 12-story mid-rise complex to fit the former site of the Prentice, with a groundbreaking slated for early 2015 and completion forecasted for 2018 or 2019. It will also serve as a base for the second phase, capping Phase 1 with a multistory tower featuring even more lab space and offices. It should be noted that there is currently no timetable or funding in place for the Phase 2 tower. Thus it is of particular importance that the design for Phase 1 does not end up looking like a vacant pedestal, should Northwestern’s long-term development goals not pan out.

The design criteria included: an iconic design that respected the campus context and would be a major asset to Northwestern, the Streeterville neighborhood, and the Greater Chicago community; a building that best met all the functional needs of the Medical School; a building that could be easily implemented in two phases; a design that respected and enhanced the neighborhood connections at ground level (particularly with the labs of the adjacent Lurie Medical Research Center); and a design that provided extensive green space. The University also expected at minimum a LEED silver ranking.

Similar to Northwestern’s most recent invited competitions, the RFQ procedure was a hybrid between a pure design competition and an interview. Or rather a series of interviews, as the shortlisted teams underwent a series of meetings during the design phase with the client group. The university prefers that the names of this evaluation committee remain anonymous, although Northwestern spokesperson Alan Cubbage has disclosed that the group included members of the University Board of Trustees as well as key administrators of the Feinberg School of Medicine. Two outside architects also sat in as advisors.

During these design meetings, the committee offered comments and critiques to each shortlisted team. Northwestern has chosen to keep the specifics of these meetings confidential, but we do know through reliable sources that the each team felt that the evaluation comments were well founded, and that no single competitor was singled out for criticism.

By November of 2013, the three shortlisted teams final designs were ready for a final verdict. In a gesture of transparency, Northwestern officially unveiled the resulting shortlist designs in an exhibit at the Lurie Medical Research Center. The university welcomed and recorded comments from faculty, staff, students, and other visitors to this public display. The three projects on display were by Perkins+ Will, Adrian Smith+Gordon Gill, and Goettsch Partners. It is good to see that all three firms have local Chicago offices; it seems fitting to replace a building by the indelibly Chicagoan architect Goldberg with a new generation of successors.

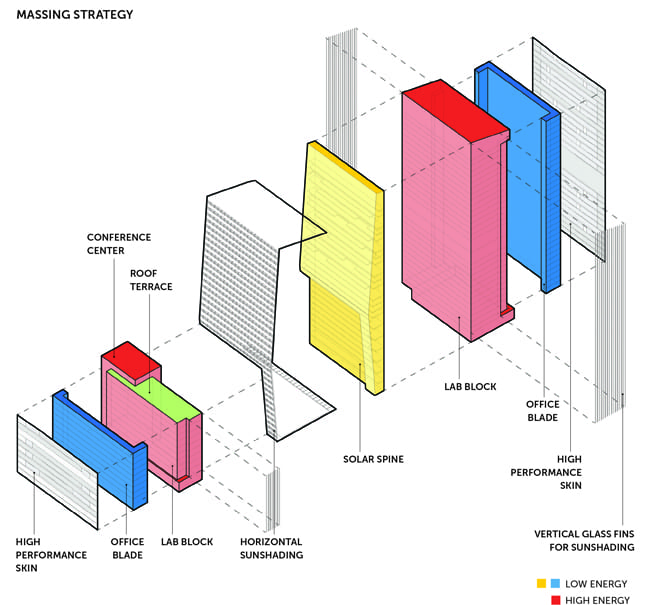

A casual observer of the shortlisted designs could be forgiven for finding them all remarkably similar. In fact, no one design stands out as wildly out of the box, an obvious winner. Instead we see three elegant, highly competent, if rather predictable options. Part of this stems from the nature of the building program—the rigid constraints of medical and research facilities often have a way of confining creativity. There’s also the persistent issue of making glazed skyscrapers energy efficient. Each entry uses high-performance building skins, which give them similar façade materiality and depth, not to mention employment of textbook sun shading techniques (cue the obligatory vertical fritted glass fins on the east and west facades). Just as the chunky Brutalism of the Prentice had become emblematic of 1970s modern architecture, the sleek, crystalline forms of the shortlist are very much of our own time. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it would have been interesting to see at least one unconventional curve ball, even if it had no chance of winning the commission. *

Out of this unsurprising but nonetheless impressive trio of designs, Northwestern ultimately chose Perkins+Will as the winner, making the official announcement on December 6, 2013.

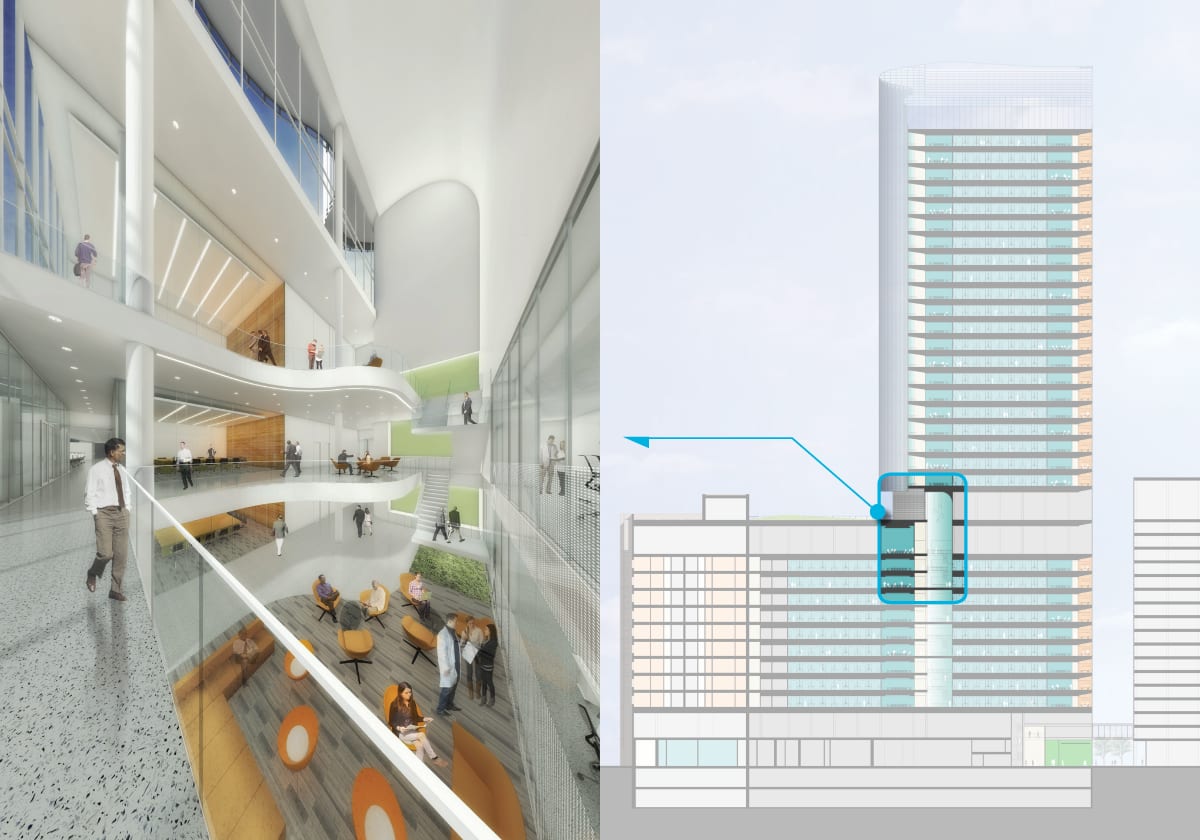

There is a lot to like about the Perkins+Will design, which was spearheaded by Ralph Johnson of the Chicago office. As a whole it is easily the most elegant of the designs. The north side presents a sleekly curved, tapered form; giving the oft-mundane Northwestern campus some much needed skyline appeal. Meanwhile the south and east facades are sharply rectilinear, reinforcing a strong street edge along Huron Street.

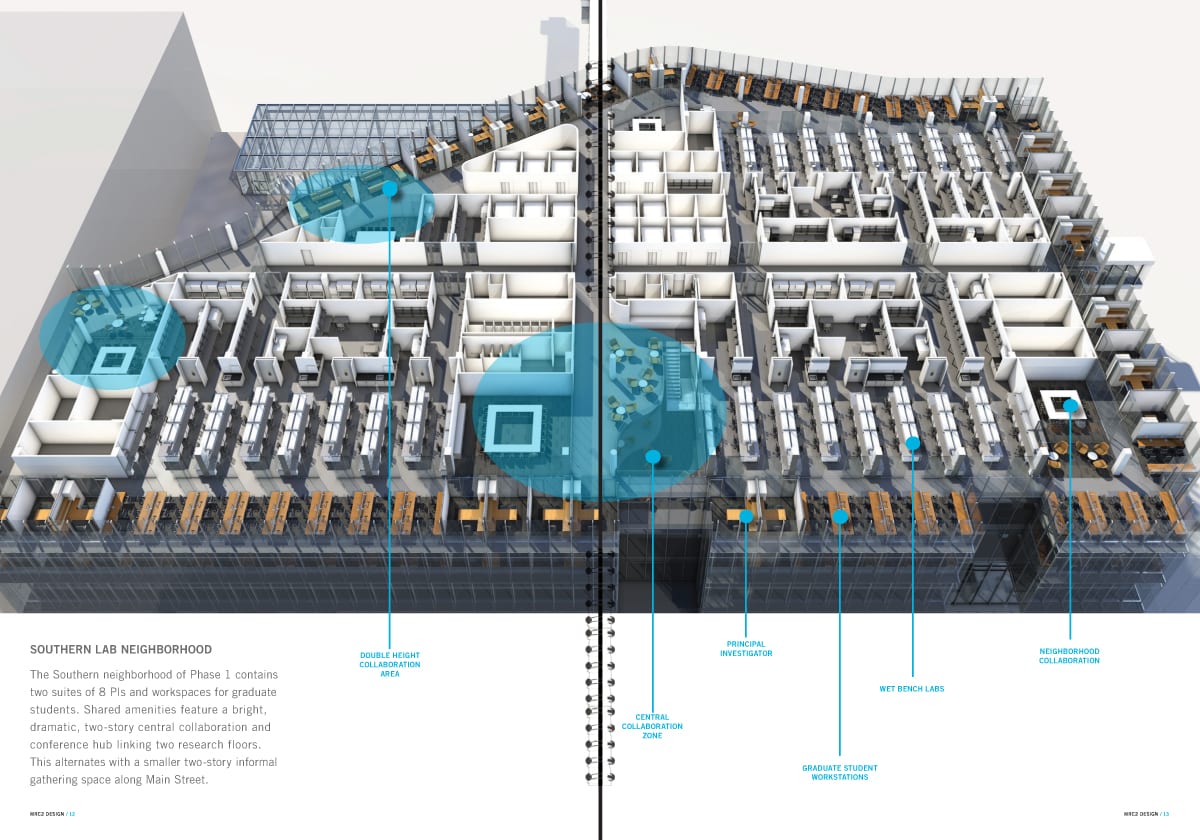

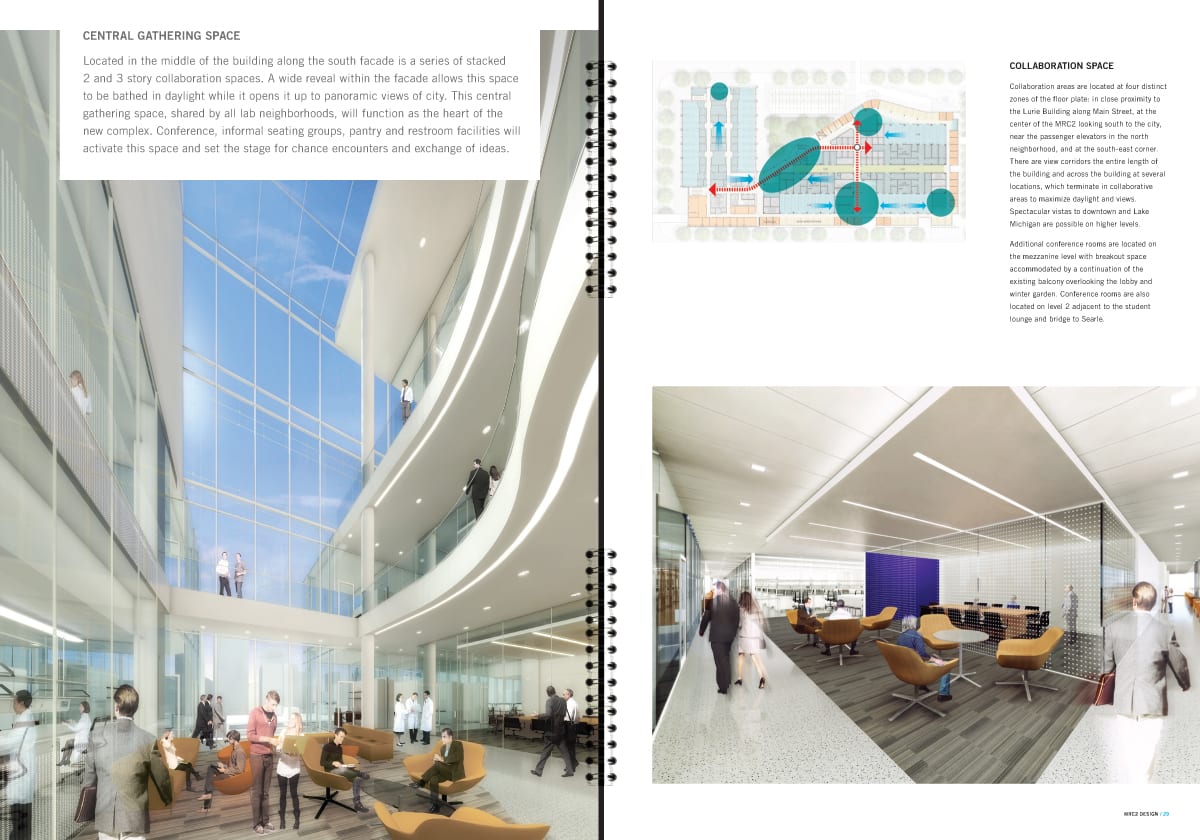

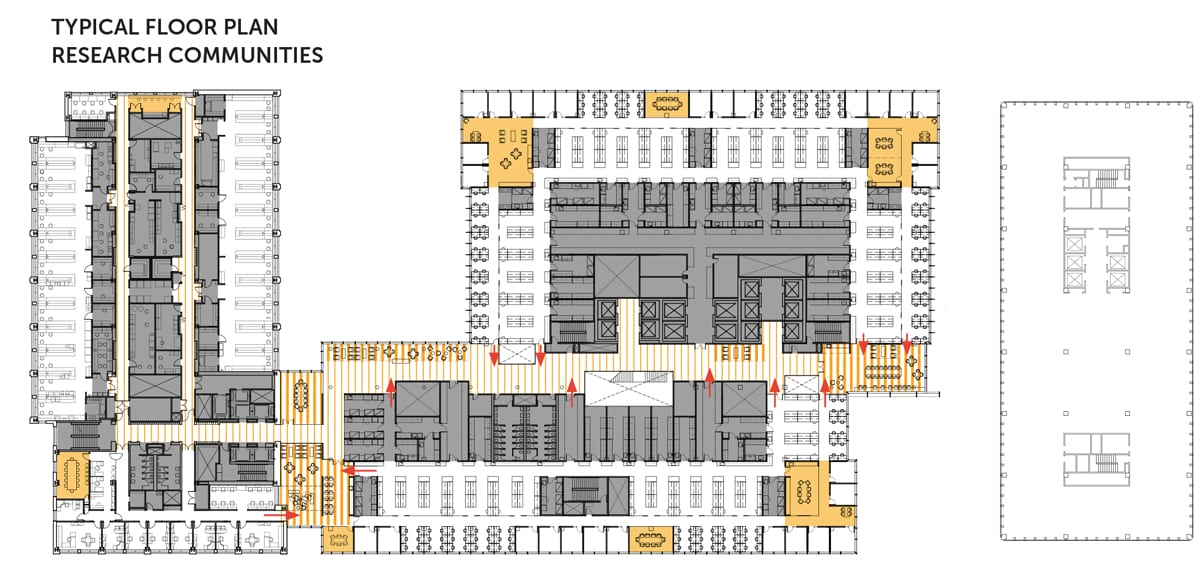

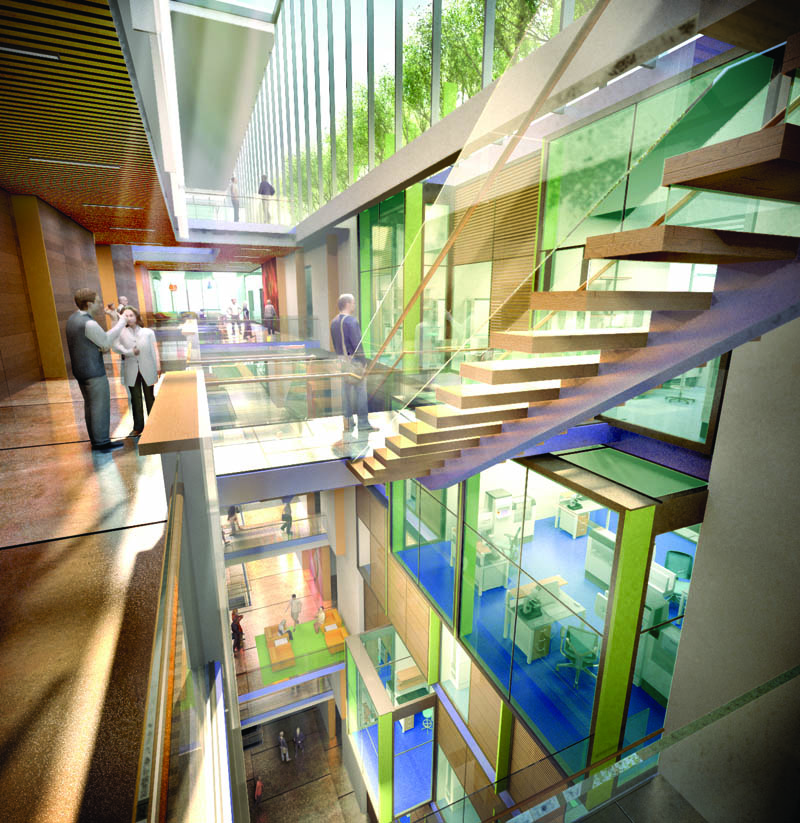

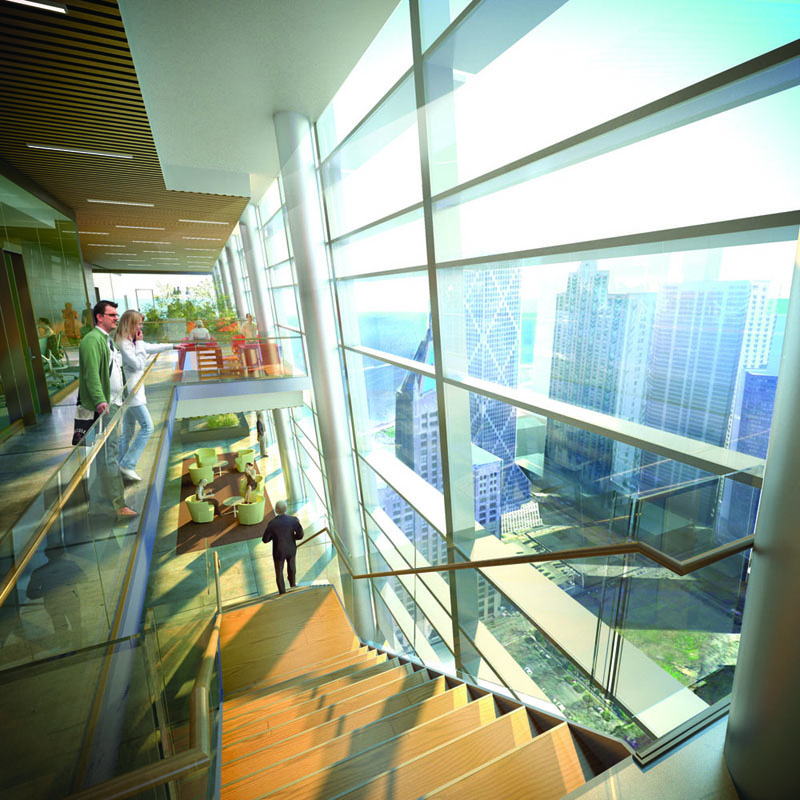

In the spirit of Chicago architects past—Louis Sullivan, Mies van der Rohe and, yes, Bertrand Goldberg—form apparently followed function. As Ralph Johnson noted, “The generator from day one was the lab plan. It wasn’t creating a sculpture and fitting in the plan. It’s all about research and labs and that’s the generator of the idea. By the time you do that, the shape of the building starts to happen.” The carefully detailed layout includes special collaboration areas meant to heighten the sense of community in the rather large building. The collaboration spaces, stacked two and three stories high, are bathed in natural light and boast panoramic views of the city thanks to their locations along the south façade. As the “heart” of the Medical Research Center, these spaces are shared by the entire laboratory “neighborhoods.”

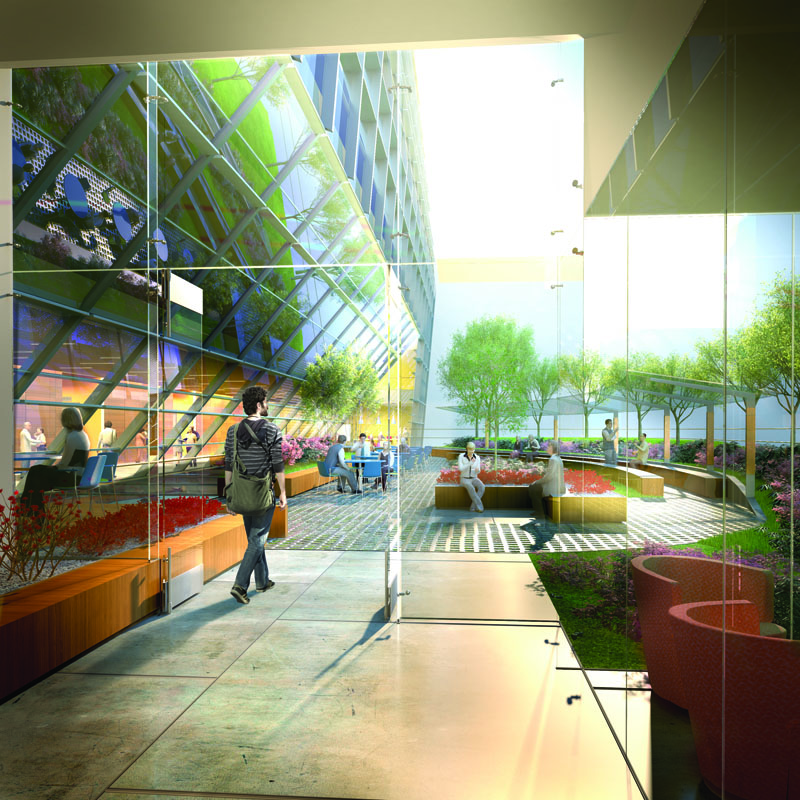

The building is peppered with landscape and vegetation: in gardens between the Research Center and its neighbors, in a Winter Garden that transforms an existing lounge space into a glass-roofed interior oasis, and in a green roof that tops the Phase 1 design. These features, along with the high performance building skin and state-of-the-art mechanical systems make Perkins+Will’s design demonstratively sustainable.

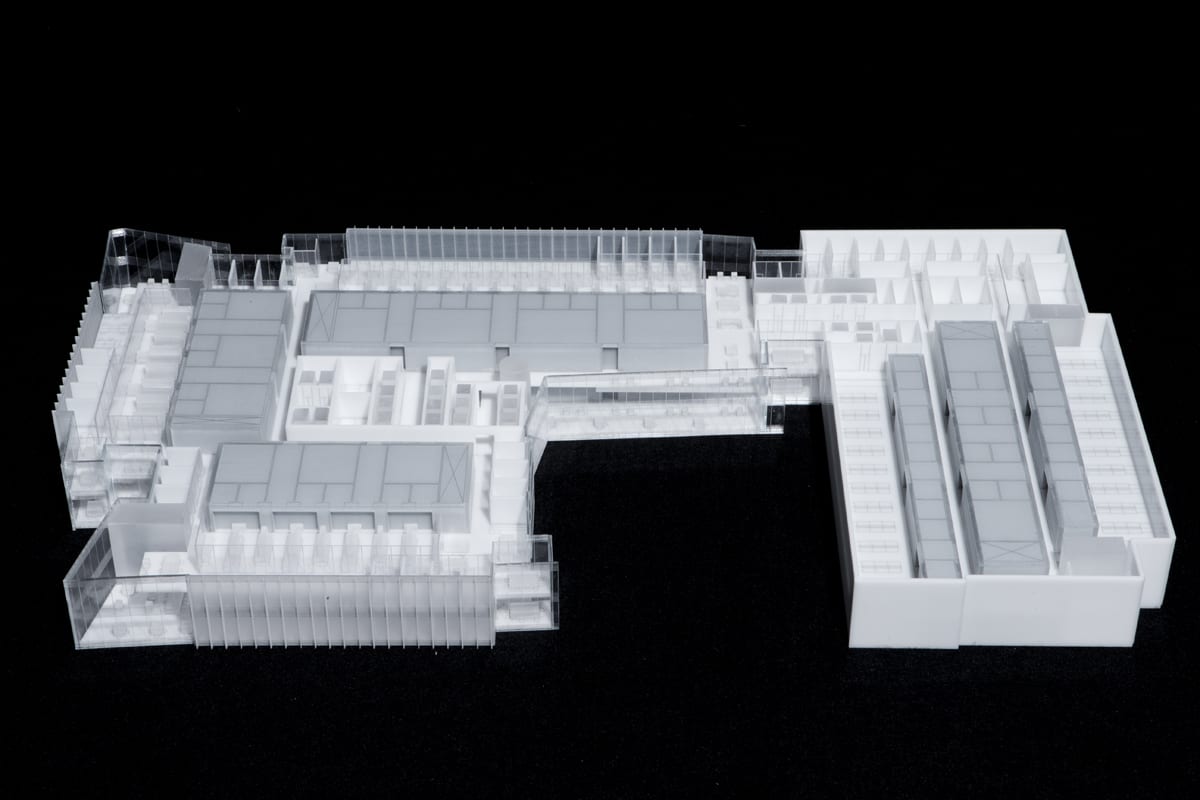

While Perkins+Will’s design may have had the most aesthetically stunning form, the entry by Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill (with Payette) has the strongest parti. The overall massing of their boxy design is defined by two shifted, parallel research bars, running east-west and bisected by a “solar spine.” One of the more intriguing concepts of the shortlist, the solar spine acts as a horizontal and vertical Main Street: organizing the building’s public life, connecting labs, optimizing views to the lake, and, as its name suggests, bringing light deep into the core of the building.

Phase One’s solar spine would extend to Phase Two’s “solar porch,” running along the south side of the tower, shading inhabitants in the summer and bringing in sunshine during the winter months. Smith+Gill referred to it as an “occupiable wall.” While it would have been interesting to see this concept implemented, the overall design of the facility is somewhat clunky, quite possibly a turn-off for the evaluation committee.

Images © Ballinger

While Goettsch Partners bagged the commission for the Bienen School of Music and Communication competition, success eluded the firm this time. Even so, their entry for MRC2 has a compelling floor-plan layout that maximizes the amount of light and views for the labs. Like the Perkins + Will design, there are multistory collaborative spaces creating various shared links between workspaces. A particular highlight is the interior tree-laden commons areas stacked vertically up the building’s northeast and southeast corners, providing pleasant informal gathering spaces on every floor. There are plenty of other great features in the scheme, but they also add up to a rather busy exterior lacking the elegance and clarity of Perkins+Will’s tower.

Is Perkins+Will’s design a fitting replacement for the embattled Prentice? There is some potential for disappointment. This past September, Perkins+Will presented an updated design at a community meeting at the Lurie Medical Research Building. The revised design was notably shorter. This six-story reduction was enough to make the once elegantly soaring tower appear a little stumpy, and the overall reaction amongst attendees was not entirely positive, to put it mildly. Are these concerns justified, or merely the minor grumblings that often occur as an initial design concept is pared down to a more manageable reality? In truth, the Medical Research Center will likely never be met with the sort of extreme reactions the Prentice withstood—mostly either negative or positive and rarely anything in between. Rather Perkins + Will’s design seems destined to fall into that in-between zone that eluded Goldberg’s distinctive hospital. But only time will truly tell.

*Another trait shared by all the designs is the conspicuous absence of the Prentice Hospital, which sat vacant throughout the entire RFQ process, still intact but unambiguously doomed. Reading the design narratives of the shortlisted firms reveals a marked contrast to all the talk of memory and legacy that the Future Prentice ideas competition centered on. Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill vaguely allude to a “strong architectural memory” associated with the campus, but never call out the Prentice specifically. Meanwhile the design by Perkins+Will looks beyond the recent built history of the campus to find design inspiration in the more historic forms of Northwestern’s Neo-Gothic towers.