COMPETITIONS: I am presently here in London to talk to my editor about a ‘how to’ book we are doing on competitions.

JOHN MCASLAN: And how not to do them, I hope.

COMPETITIONS: You’re familiar with one of those?

JM: We recently did one—Middlesborough Town Hall. It caused a real furor here.

COMPETITIONS: Usually the RIBA competitions are well organized.

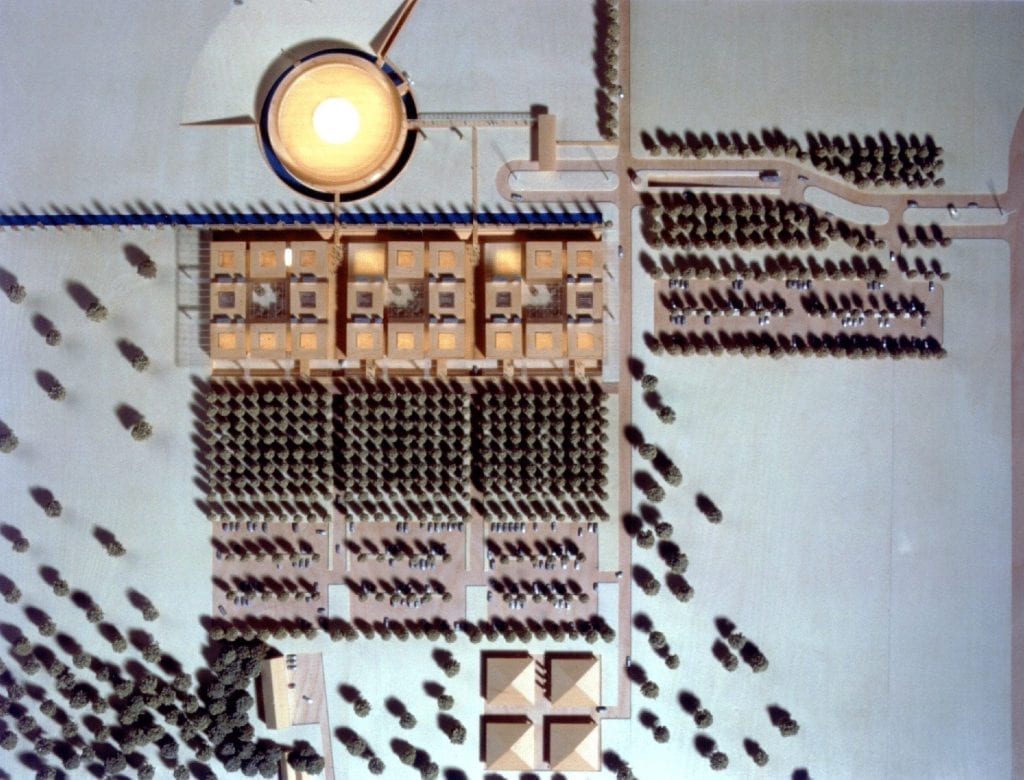

Science Center, Florida Southern College (1996-2001)

JM: This was an open, non-RIBA competition to re-market (rebuild) the Town Hall in Middlesborough, a town which had quite a good artistic tradition. About ten years ago they commissioned Claes Oldenburg to design a sculpture. There was also a competition for a museum there—which we didn’t get. And then there was the competition for the Town Hall, where we got to the last six. It was chaotic, as to what was to be submitted. There was a lot of to-ing and fro-ing, because the terms of reference weren’t clear. And then there were long delays before the interviews. Finally we were asked to submit a tender(fee bid). But of the six tenders, only four arrived on time. Because of that, the two late tenderers were eliminated. I thought, ‘well, you know you have to get them in on time.’ But then one of the jurors walked out, because she thought it unfair that these two had been eliminated. Then it came out that they had opened the bids before the interviews took place.

We were only runners-up; but the whole thing has caused chaos because of the sloppiness with which the whole thing was organized. They should have selected the preferred team , then opened the bids.

You asked about the RIBA competitions. We have won some and lost a some. But you can say that they are always immaculately organized—very transparent, no confusion over what is required when. If a competition is badly administered with lots of criticism, it doesn’t help at all, especially with funding.

Science Center, Florida Southern College (1996-2001) Lab interior (left) and model (right)

COMPETITIONS: You were recently in the Fresh Kills competition in the U.S.

JM: The Fresh Kills competition, which we didn’t win—we were the second team—was run by Bill Liskamm. The whole competition was superbly organized. One thing I like about the American competition system is that the second-ranked team is in line for negotiating a contract if an agreement with the preferred firm cannot be reached. Here it is simply a matter of the team with the lowest tender.

Fresh Kills only fell down once: we found out after having been interviewed (Bill was no longer involved) for the shortlisting, but before the final stage, that the preferred team—just after the announcement of the rankings—made a private presentation to senior officials on Staten Island. This was in advance of the final bidding stage. If all three teams rate on an equal level—albiet that Field Operations went into the final stage ahead—surely we should all get a chance to present.

COMPETITIONS: How about your overall experience with competitions?

JM: Our success rate in competitions is so varied and so unpredictable that I think we are getting to a point as a practice where our reputation will get us on shortlists. As for the different types of competitions in this country, we have the competitive interview—which is the one we like. You don’t have to do a great deal of work, and you try to win it on, ‘they like you; they like the experience and the team you bring.’ It’s the least time-consuming.

The second is to compete on a short, sharp brief. We just won a competition about two weeks ago (not yet announced at the time of the interview -Ed) for a school which was part of the Government City Academies Program and takes poor inner-city areas as locations for new secondary schools, often by amalgamation of other schools. It’s a combination of public and private funding, which is quite unusual in this country.

It was a good competition because you are a participant in a 30-firm framework, and each firm gets an opportunity to be interviewed several times for a variety of the projects. But in our first interview we did terribly. We actually didn’t even visit the site, which was criminal. But there was no program; nothing was asked for. In the second one we did an approach which just didn’t work. At that point we decided that ‘this was three strikes or you’re out,’ as you say in the U.S. We made quite an effort, just developing a little model—of what it could be. I could tell once I saw the finished model that we should win. When we went into the interview, it was thought we weren’t the preferred team because of our lack of secondary school experience. But we won it because we were energized, especially for the interview, and the jury also found the model compelling. I felt we were very comfortable with what we had developed and that we were the right team. But it wasn’t weeks and weeks of work.

Then there is the competition where you slog your guts out for a scheme, and you don’t win. That’s such a waste of creative time and very frustrating. Then there is the rare situation where it is a fee bid only. Normally they are a combination of fee bid and design. I think the client should go to the preferred team (before opening up the bid) and try to negotiate with them to make it work, rather than opening up the bids beforehand., which prejudges and colors people’s opinions. If the preferred team’s bid is ridiculously high, negotiate the fee down, or eliminate them because they have underestimated the scope and prepared an unrealistically low bid.

COMPETITIONS: What about competitions outside the U.K.?

JM: We love international competitions, and I must mention here that we just won one in Beijing for a mixed-use, office-retail building for a developer, Suntrans. There we won the competition for one building in a larger complex. The masterplan was by SOM. There was a recent one for the Stavanger Concert Hall, in Norway. It’s a good competition; but we can’t afford the time right now. It’s important to be ruthless about ones which you can’t afford. We realized we just didn’t have time to do it well.

Finalist: Nairobi Al Jamea Campus Competition (2013)

Clockwise from left, above: Mosque entrance, plan, main square, view to Al Jamea gateway

COMPETITIONS: How do you estimate the cost of doing a competition, and how do these financial considerations come into play?

JM: One other thing we’ve begun to do—and consultants don’t always like this—is tell the engineers, etc. who are part of our team that we are going to split the costs relative to their fee. So let’s say that the architect’s fee is 40%, the engineer’s is 30% and the others are 20%. Ours includes the cost of the vision and model and carry all of our time. But we must all share the cost of the deliverable. It’s amazing how people run away from that. Very good firms like Davis, Langdon and Everest, who are the best cost consultants, say that they don’t have a budget for competitions. I say, ‘You have a huge company with hundreds of people, and we only have sixty people here. Why should we be funding the whole competition. If you are part of our team, and you are going to be appointed, then you must carry your share of the cost. Arup needed to be persuaded kicking and screaming; but they generally go along. They did it with Fresh Kills. Compensation was $50,000, and our costs were several times that. So we carried our time, but split the production costs. Unfortunately we couldn’t persuade our other consultants to do that. Some firms may be able to afford to do otherwise.

COMPETITIONS: Some firms like Rafael Viñoly have a financial cushion after doing well in a competition like Tokyo Forum.

JM: Everyone needs a golden nugget. Historically, we have had a few projects like that. When we are on resource-based fees, every hour we work, we earn, and it bankrolls the practice for competitions/

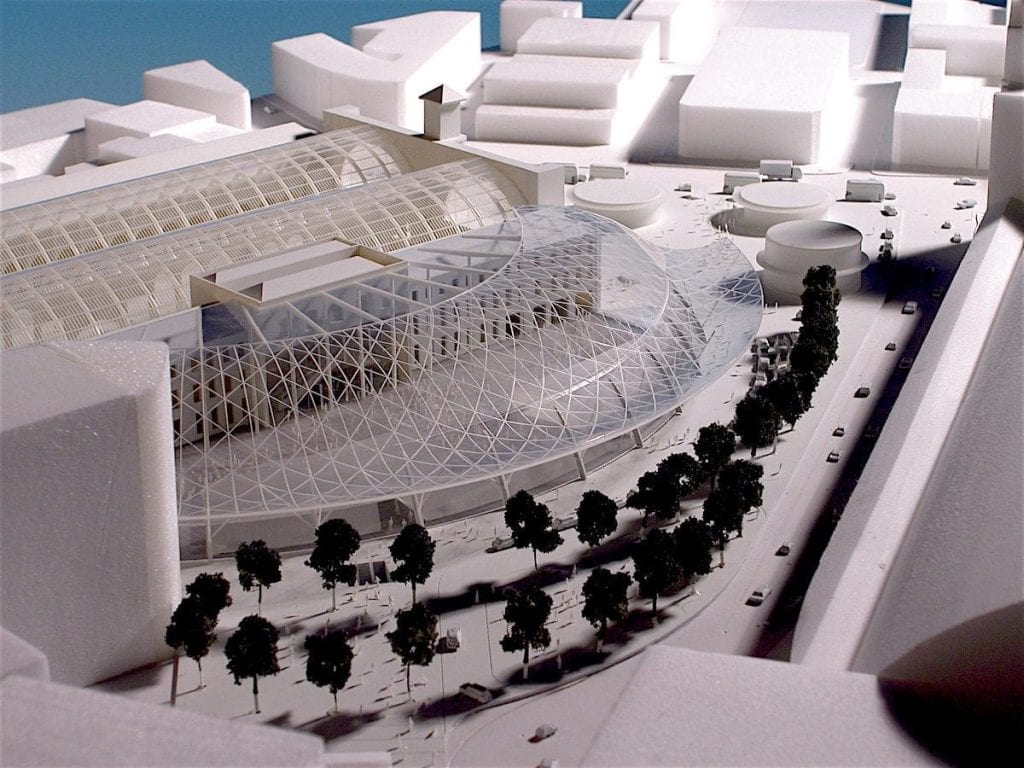

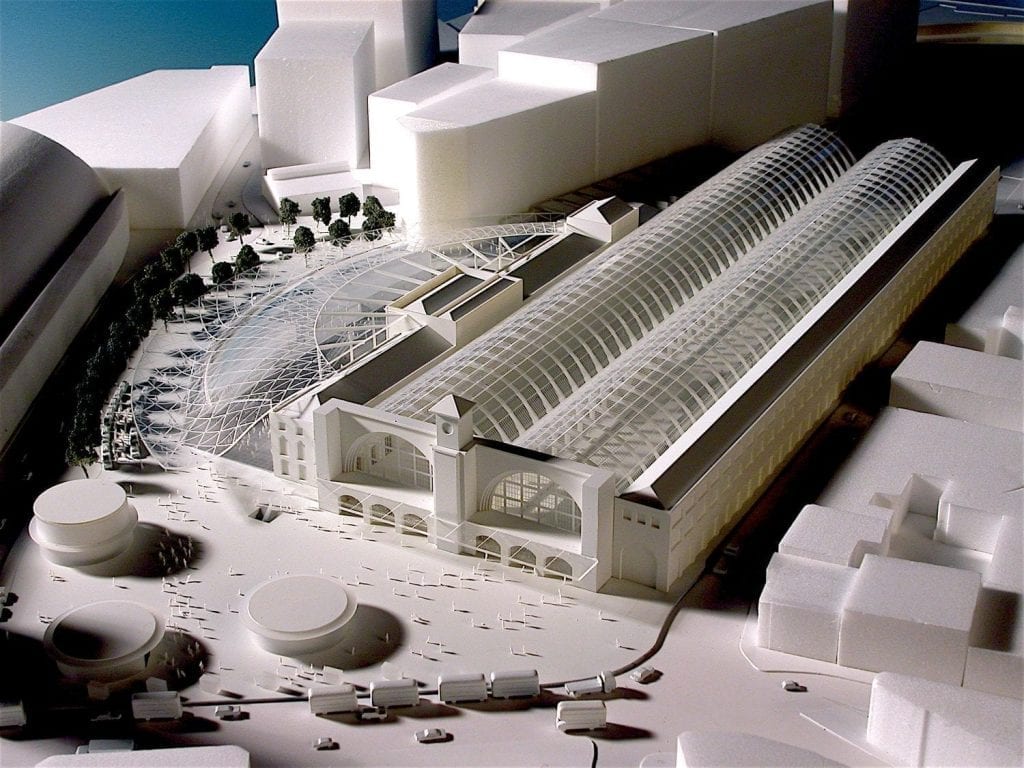

King’s Cross Station (Competition 1998; completion 2011) Competition models (above)

King’s Cross Station (Competition 1998; completion 2011) Upper level rendering

COMPETITIONS: Do you get many contracts on a non-competitive basis?

JM: Most of our work comes from competitions. It’s amazing when a job comes along which you are not competing for. We are doing a couple of projects in Manchester with a very good residential developer, Dandara, both of which came directly to us. I had to ask them at some point, ‘We aren’t competing for this, are we?’ They said, ‘No, it’s your project.’ For us this is almost unheard of—that a client will offer you a project uncompetitively.

A lot of our work is long-standing. Our biggest project, which is King’s Cross Station, we won in a competition in 1998, and that project is now really only coming to fruition—5 years later—and won’t be completed until 2011. When you think of the gestation period, the various permutations, and the master planning, we’ve worked through the client’s business case; it’s changed from Railtrack to Network Rail; a whole different set of scenarios in terms of how the interchange will be resolved. After five years, we just now have the design resolved.

A project which we just finished—the headquarters for Max Mara Fashion Group—a campus with showrooms, offices, and distribution, is from a competition which we won in 1995. To sustain a project in an office for that length of time is hard work—and letting the client feel that you are still concerned with their project. But we did it, and the client is very happy with the result.

COMPETITIONS: Sometimes the client can change.

JM: In some of these long projects, we are the only people who are still around. The De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill, an Eric Mendelsohn building from the early 1930s, was a competition we won back in 1991. We are the only people still left. When we won it, it was before the National Lottery, and Bexhill was a town with no money. The man who was a socialist mayor of Bexhill in the 30s, organized the competition; Thomas Tate, a well known Scottish architect, was the senior assessor; and Mendelsohn with Serge Chermayeff won the anonymous competition. We won the competition by telling them that ‘There is no point in us coming to you to tell you how you are going to transform this building, because there is no money, no artistic program in the building. You have to develop a plan to take this building, which has bled the authority for over 50 years, to minimize its losses.

We won another competition for the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama after a very good, rather lighthearted interview, although we were up against very good people. We won it on a miserable answer I gave to a question. The last question—which is the one they said won it—was ‘What is the single most important thing that you think you can do for us?’ I thought a long time about this and, knowing that the school was very worried money, answered that ‘My key responsibility is never exposing you to risk.’ And we won it on the basis that they thought they could trust us to look after them—not make them spend money they couldn’t afford. The first stage includes demolishing some of the existing buildings and designing a new concert hall, which is about to begin construction.

COMPETITIONS: What happens in a case like Middlesborough, when you believe you have the best idea but don’t win?

JM: The best thing you can do when you have done a competition is to put it away, and never think about it. Frank Gehry said, ‘If they want you, they want you. If they don’t they don’t.’ I share that view of the world. Our generation of architects competes against the Fosters, etc., and you have to offer a distinctive product which sets you apart.

The “Roundhouse” is a competition which we won about six years ago. It was an old engineering building, a fantastic cast-iron structure. At first the client who had bought the building went straight to Foster and worked with them for about a year. In order to get public funding they had to go to the public board. Foster entered, we entered with a number of name firms. I was amazed when we were appointed. I never asked, but I think we won it because we were right at the time, and the budget—about £15M—was too high. I told him that he should be spending no more than £8M. I said, ‘This building has a raw kind of energy. Don’t try to overdress it.’ And I think again that we got the job because we were very cost-conscious and would protect the budget, while responding to the essence of the project.

COMPETITIONS: How has past experience determined the composition of your firm?

JM: In the late 70s I was in the States—with Cambridge Seven. There I really liked the mix of disciplines I saw. Then I went to Richard Rogers, and that was a single head studio. Both were good environments to work in. I always thought if I opened an office I would like it to be a ‘loose’ studio, non-hierarchical, and give people a sense of ownership. Here we have a multi-skilled, multidisciplinary practice—architecture, landscape, urban planning, our own visualization team, model-building, research units.

I’ve always liked the idea of a multidisciplinary design studio. I was amazed, for instance, to learn that SOM here, with 120 people, has only one landscape designer, one model-builder. We have three model builders and five landscape people on staff. We also have a profit-sharing scheme, where everybody shares in the profits of the practice. This year was profitable, so I hope that the people here will be surprised and pleased when they receive their bonuses.

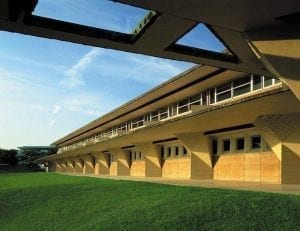

Next year I’d love to win a commission in America. I have connections there, as my wife is from there, and we did finish a project there last year (Florida Southern College). We have a lot of experience doing educational facilities; so why shouldn’t we be doing something there? Some architects travel well—as in working overseas. We are like that.