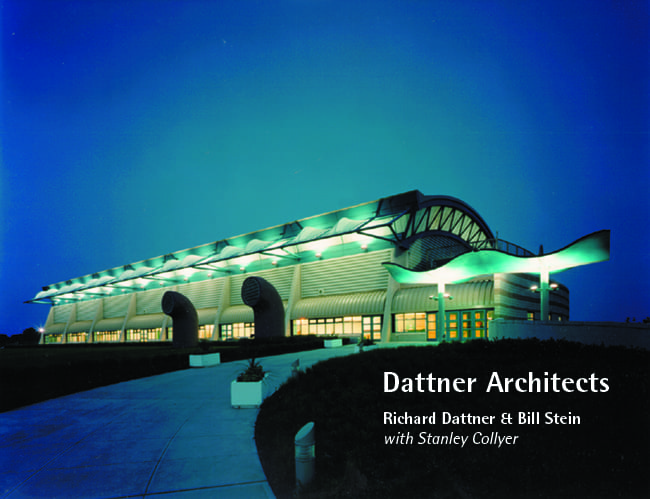

Goodwill Games Swimming and Diving Complex, New York, NY (Photo: Peter Mauss/ESTO)

COMPETITIONS: What led you to choose architecture as a profession?

RICHARD DATTNER: It’s a little like Dustin Hoffman in the movie The Graduate. I already wanted to be an architect in the seventh grade, when I was building architectural models. When I was in high school, somebody whispered to me “electronics.” “Since architects don’t make money, you should study something that has a real future.” So I actually went to MIT thinking I would become an electrical engineer. I realized you couldn’t see any of those little things zipping around—the electrons, etc. My next door dorm-mates, actually three architects from New York,–Andy Blackman, Peter Samton and Jordan Gruzen, were three years ahead of me and were having a lot of fun—building models, beautiful girls came in and out of their dormitory rooms. I thought, “I’ll have what they’re having.” Luckily, at MIT, the first year is the same for whatever your major will ultimately be; so I switched back to my original love. From there, I never looked back.

COMPETITIONS: MIT was different than Harvard when you were there. At Harvard, where they had very strong deans—Gropius and Sert—everything that the students turned out looked pretty much the same. At MIT it was different.

RD: MIT was a kind of ‘Let a Hundred Flowers Bloom.’ They had some wonderful people, some of whom were rejects from Harvard, .i.e. Joseph Hudnut, who had been the dean at Harvard. Other great professors included Lewis Mumford, Kenzo Tange, Leonardo Ricci, Georgy Kepes, Richard Filipowski, Lawrence Anderson, etc.

COMPETITIONS: What effect did your stay at the Architecture Association in London have on you?

RD: During my junior year at MIT, I had an opportunity to take the middle year of my 5-year stay at MIT at the AA. There I had a similarly interesting roster of people—James Stirling and many of the British “brutalists.” It was a good antidote to America. In those days in America, Edward Durrell Stone was the hero, producing a kind of “surface architecture,” which by the way is probably going on today. So what goes around, comes around. When I was in London in 1957/58, London was still recovering from the war—there were still bombed-out sites. So architects were much more brutal and honest—Corbusier was a hero. The London County Council was doing incredible social housing, some of it based on the Unité d’habitation of Corbu. There was a lot of fascinating school design going on. As an interesting time, it was a real kind of antidote to the postwar, feelgood (trend) then current in the United States.

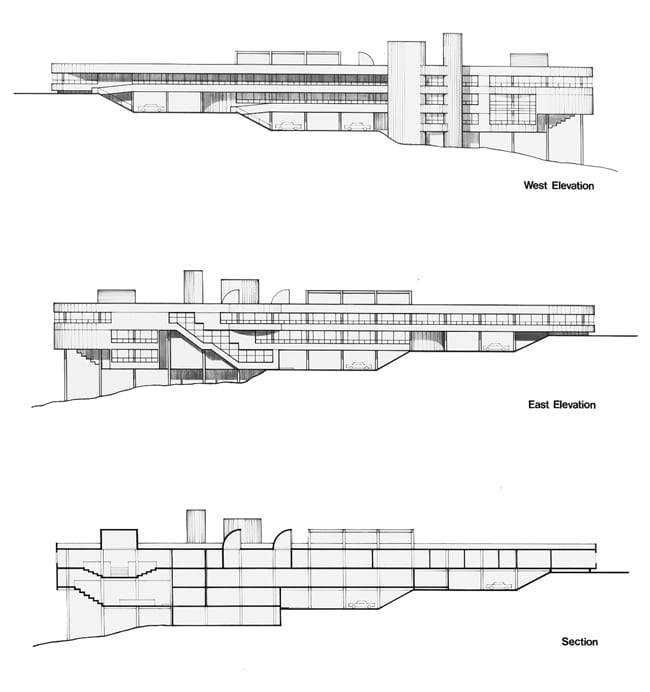

Courtlandt City Hall, Courtlandt, NY – Winning Competition entry, 1976 (unbuilt)

COMPETITIONS: When you started your own firm in New York, you were doing a lot of playgrounds. Is there some kind of logical progression from that genre to designing schools?

RD: I started my career in playgrounds in the 1960s, worked for a number of offices in New York (and got laid off by many of them). It was difficult for me to work for other people and I got the opportunity in 1964 to design the Estée Lauder factory with Sam Brody—we were both teaching at Cooper Union at the time. Shortly after that, the Lauder Foundation asked me to design the Adventure Playground. From those two projects, both for Estée Lauder—the factory won a national AIA Honor Award when I was 27 years old—most of my work subsequently flowed. The industrial/commercial work resulted from the factory, and the public work really flowed from the playgrounds. After I did the playgrounds, I was put on a list for a public school in New York City, and I was awarded a public school in 1969 when I had a tiny office. From those beginnings we’ve grown to an office of some 70 people.

Estee Lauder Laboratories, Melville, New York – 1972 (Photo: Kevin Chu + Jessica Paul)

COMPETITIONS: How did the Estée Lauder project come about?

RD: It all started with a kitchen renovation in a brownstone, which I really didn’t want to do; but my wife encouraged me to go ahead with it. So I went ahead and designed this kitchen. After that a family saw my kitchen and asked me if I would like to do their brownstone. I did the renovation of the brownstone, and the contractor who did that job mentioned to me that he had a neighbor who wanted to build a factory. “Had I ever done a factory? No, but I could do one.” Since I was working out of my living room, I joined up with my colleague at Cooper–Sam Brody–who then had a small office of five people, and we made a presentation to Leonard Lauder who had a small company of about 50 employees in New Hyde Park. He was interested in doing a warehouse/office/factory building on Long Island and narrowly picked us over somebody that was just going to build him a speculative building. Our design was a porcelain enameled round-cornered building. That is when won a national AIA Honor Award and we got a lot of publicity from that. The continuation of that story is that next month I am going to Belgium to design the second phase of a factory for Lauder—we did the first phase 25 years ago. So that relationship has continued since 1964—always together with Davis Brody. Sam Brody passed away some ten years ago, and I now work with Steve Davis. Now Lauder has 15,000 employees, and they are all over the world.

Estee Lauder Distribution Center, Lachen, Switzerland – 1998 (Photo: Courtesy Dattner Architects)

COMPETITIONS: Your firm only enters competitions periodically. I assume it’s one of those pick and choose scenarios.

RD: The downside of competitions are: [1] you might have 800 entries, and [2] the project may never get built. When I started practice, there were no computers, so entering a competition as a single person was questionable; but now, a single person with a computer can turn out anything. They may not be able to actually produce the project; but they can certainly produce the design.

COMPETITIONS: When established firms ask if they should enter a competition, my response is usually the following: Entering can be justified if it is a building type they have never built but are interested in. It’s a learning process which can provide the firm with expertise in that area.

COMPETITIONS: Recently, the Behnisch office in Stuttgart mentioned that morale in the office improved when they began putting three or four people on competitions all the time as a standard practice. This during a long period when the entire office had been consumed with a mega-bank project.

Bill Stein: That’s great if you can afford to finance that. Architects love competitions and are never happier when they are working for no money.

above and below: No. 7 Subway Line Extension, New York, NY (renderings: Courtesy Dattner Architects)

New York City Subway – 7 Line (diagram: courtesy Dattner Architects)

New York City Subway – 7 Line (Photos: ©David Sundburg/ESTO)

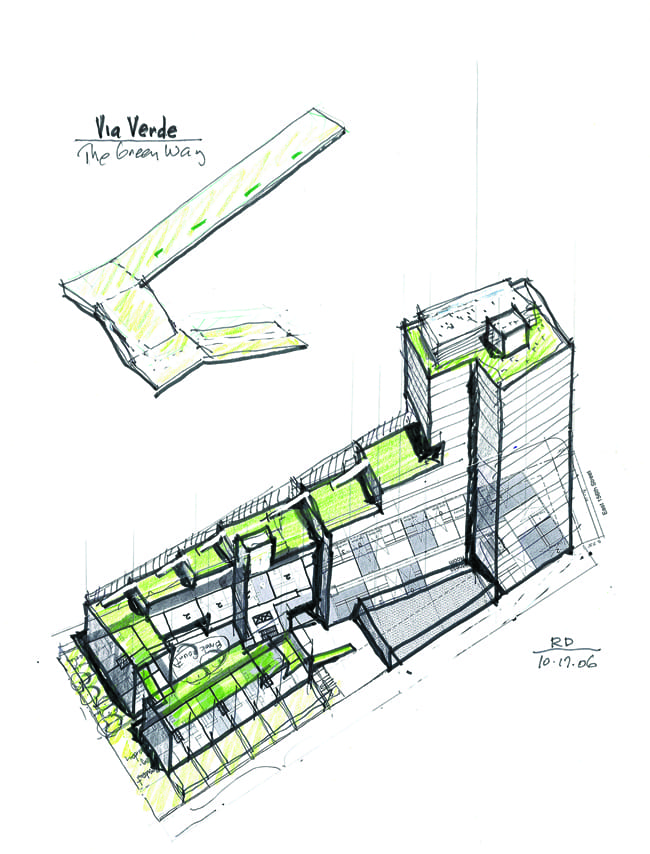

“Via Verde” First Place New Housing New York Competition (2006) (all photos:©David Sundberg/Esto )

BILL STEIN: There was a similar dynamic among the client group. Phipps is more of the nuts and bolts, understanding the real problems of maintaining and operating housing, whereas Jonathan Rose Company, although they have certainly done building and understand the reality of building, may have more of an visionary approach, although very practical at the same time.

RD: So that combination resulted in a scheme that was both fresh and innovative, but constructible. There were 8-10 architects working on this, which should give you an idea of the economics of the competition process. One thing we were very firm on was, “we’ll enter the competition and sort of bet the ranch, but we want to make sure that the ranch is built if we win it. We didn’t want to do a pie-in-the-sky design that could not be realized.

BILL STEIN: I think the other team members felt the same way.

COMPETITIONS: There must have been compensation on the front end?

BILL STEIN: $10,000. You have to understand that that is a tiny amount of money from the architects’ point of view; but from the city’s point of view this was almost revolutionary. For them to lay out money for a design competition—I think they were very proud of being able to do that—so what they did was a two-stage competition, the first being a solicitation of qualifications from developer/architect teams. They got 38 responses, and from that they short-listed five teams, and each team received $10,000. From the city’s point of view it was breaking new ground. From our point of view, the compensation was very minimal.

COMPETITIONS: In most limited competitions, firms have an eye on their competitors, and often think about how they can differentiate themselves from them. In this case did you just think about doing your own thing and ignore what others might do?

BILL STEIN: I can well imagine in another case, not in a competition, where an another architect might do this, so we might do that. In this case, we didn’t take that approach at all. We just thought about the problems and our best response to the site and the program.

COMPETITIONS: Any idea what might have tipped the scales in your favor in this case?

RD: I think it was a combination of practicality—that it could actually be built—and yet the kind of interesting approach of varied scale, varied kind of housing, the solar access of the building, stepping down from north to south. I think our clients helped to tip the balance, because they are people who can both build and operate this kind of project.

BILL STEIN: I think we had a great design, and people probably appreciated that; but this was not purely a design competition. It was a competition that the City actually wanted to see built.

RD: Bill has a point. Often one wins a competition with a scheme that is so dramatic, and basically unbuildable without raising two or three times the amount of money that a normal scheme would. So it’s all or nothing. The client can say, “this is fabulous; we’re going to raise $100M to do it.” But three or four out of five times they can’t do it; and very often it sinks under its own weight. This (NHNY) was a competition also, not in the sense of an (open) design competition; we were the small local firm which won.

Bronx Library Center, New York, NY (Photo: Jeff Goldberg/ESTO)

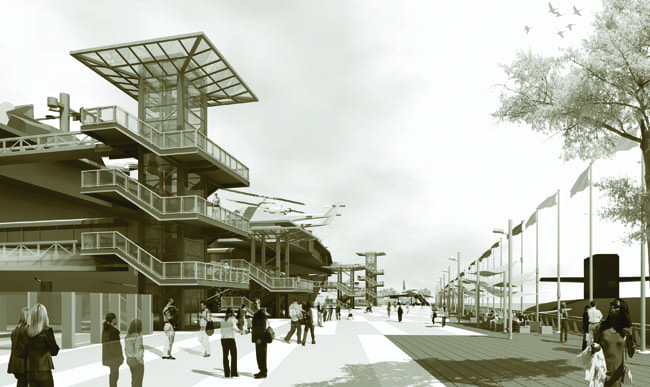

USS Intrepid Sea, Air and Space Museum Master Plan & Renovations, Bayonne, NJ

One of these projects was a limited competition, where four groups submitted proposals for Pier 40, the old Holland American Line. Our competitors are proposing things such as the Cirque du Soleil, an entertainment complex and movie multiplex and shopping mall. The community is very up in arms against it because of the traffic it will bring. My group, the CampGroup and Urban Dove, propose a much smaller intervention with recreation space pretty much like Riverbank State Park, which we designed. There is another competition for Piers 92 and 94; we’re working with SMWM for Vornado Realty Trust and Merchandise Mart from Chicago to do an exhibition/conference center for (trade) shows like NEOCON. The city’s Economic Development Corporation sponsored this, invited bids, and has narrowed it down to two teams.