Mesa’s Answer to Urban Sprawl: The Major Redesign of a City Center

by Stanley Collyer

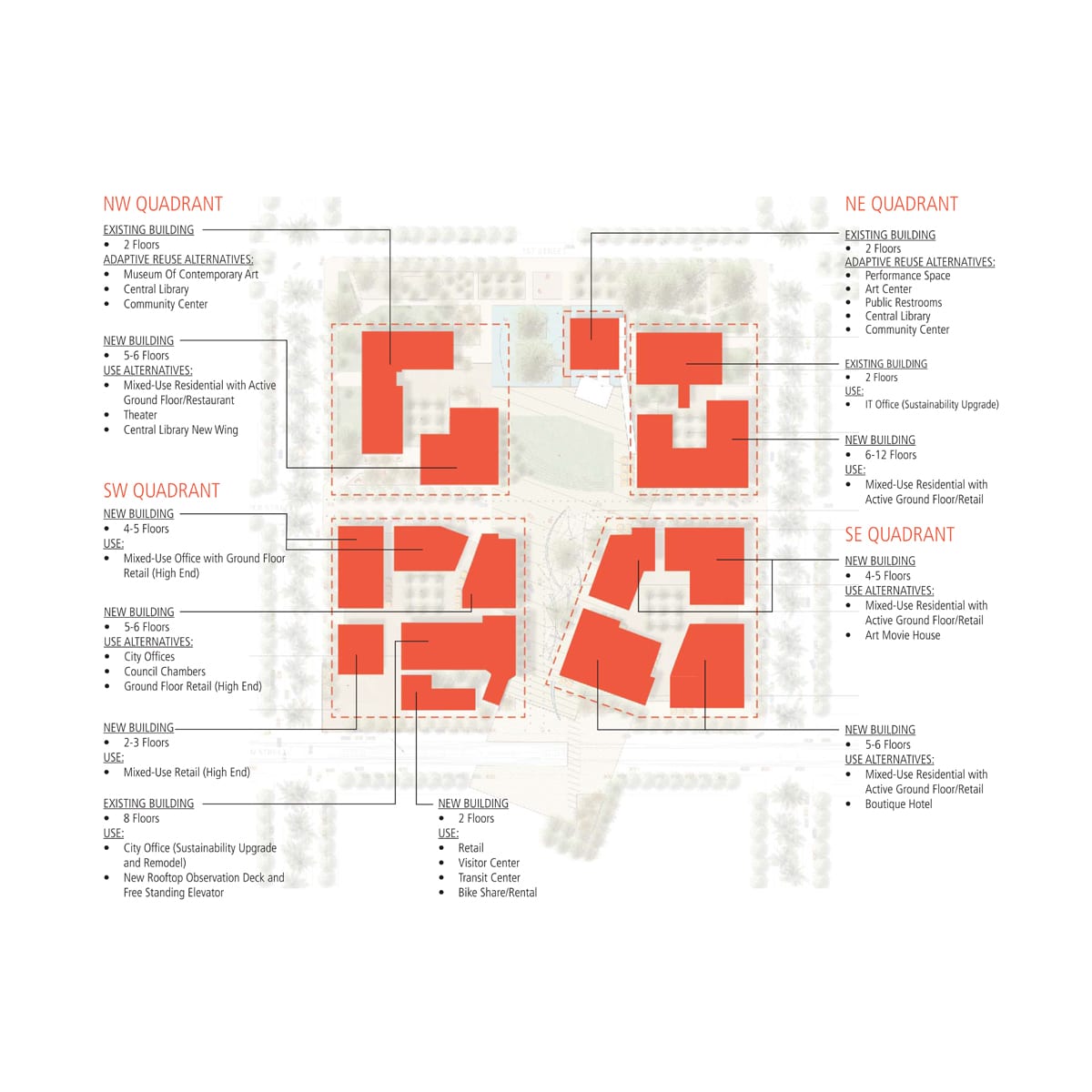

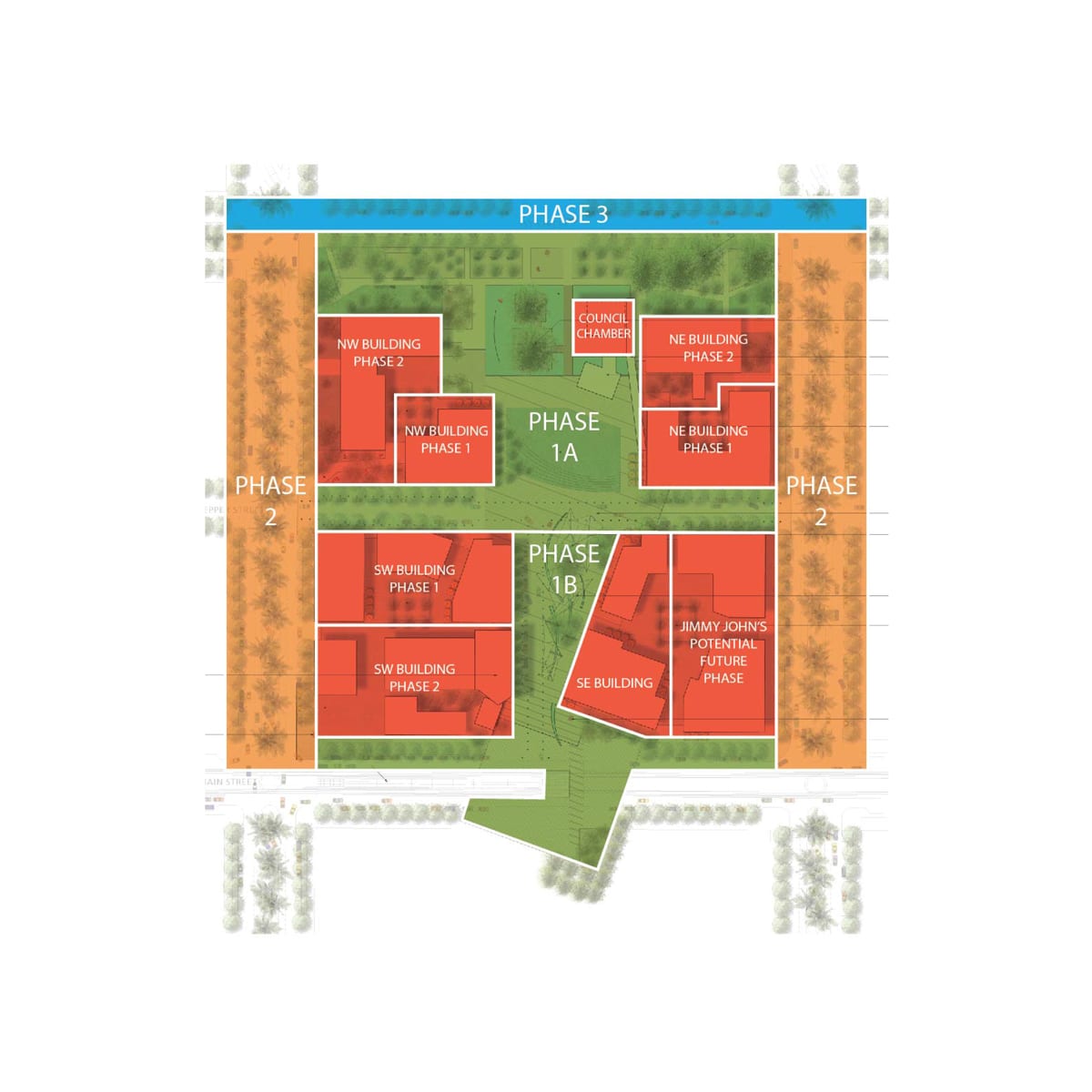

Winning Entry – Image courtesy Colwell Shelor Designing a city plaza as a “people place” is no small challenge. One only has to recall the various redesigns that Pershing Square in Los Angeles went through, or Seattle’s Pioneer Square, to recognize how intent and reality were often in conflict. In both of these temperate climate municipalities, the image of an otherwise welcoming destination was tarnished by an unforeseen presence of the homeless. The City of Mesa, in sunny Arizona, believes that a new plaza, well connected to the surrounding urban environment, can present “a signature public space” that will not only serve as a destination for public activities, but also as a catalyst for downtown revitalization. It would appear that a number of favorable conditions already exist: city administration buildings are located directly within the two block site area; Arizona’s largest art center borders the area to the south; and the city library is in the block immediately facing the site to the north. With this kind of built-in pedestrian activity, the site should be well positioned to attract a higher-than-average number of locals and visitors. To flesh out the best design for the 18.3-acre site, the City decided to stage an invited design competition. The first step was a call for expressions of interest, to which 18 firms responded. Of these, three were shortlisted to compete in the subsequent design competition. The competing teams were undoubtedly aware of the passage of a $70M City bond issue, which is allowing Mesa to allot $750,000 for design of the plaza site. Because this was a real project, each firm was to receive $25,000 upon completion of their entry. Under the supervision of Jeffrey McVay, a planner and the Manager of Downtown Transformation, a committee made up of principals from the City administration with only one exception—the Director of the Downtown Mesa Association—convened to arrive at a shortlist for the competition. It consisted of:

- Jeffrey McVay, AICP – Manager of Downtown Transformation

- Christine Zielonka – Director, Development and Sustainability Department

- John Wesley, AICP – Planning Director, Mesa

- Marc Heirshberg, CPRE – Director, Parks, Recreation, and Commercial Facilities

- Cindy Ornstein – Director, Arts and Culture

- Zac Koceja, RLA – Landscape Architect, Engineering Department

- Vincent Bruno – Engineering Designer, Engineering Department (At time of competition, he represented the Transportation Department)

- Lori Gary, CEcD – Project Manager, Office of Economic Development

- David Short – Executive Director, Downtown Mesa Association

The selected finalists were:ÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ

• Woods Bagot, Sydney/Portland (lead) with Surface Design, INC., San FranciscoÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ

• Colwell Shelor, Phoenix (lead) with West 8 urban design & landscape architecture, Rotterdam/New York and Weddle Gilmore, Scottsdale, Arizona

• Otak, San Francisco (lead) with Mayer Reed, Portland, Oregon ÂÂ

This initial phase of the competition was replete with site visits and public forums and left no stone unturned when it came to interaction between the competing firms and the client and public. The City thought this phase of the process worked well, and the Colwell Shelor team was especially active in fielding public input during this phase. Each team then had to translate those public priorities into a feasible design concept. As they say, this is where the rubber hits the road.

The Finalists Otak / Mayer Reed

Image courtesy Otak The primary strategy of the Otak / Mayer Reed team was a “Living Room Plaza,” featuring a great lawn, significant pool as water feature, and generous structural shading providing outside seating for leisure and café-style areas. A performance area featured a “Digital Light Bar” for viewing and enough paved area to accommodate outdoor market activity. Minimizing the paved area was one of the strong features of this proposal, and generous tree plantings were extended to the main thoroughfares bordering the site. On the other hand, there was the suggestion that a number of additional buildings be added to the site, configured in a way to form several courtyards. At first glance, the presence of a great lawn suggested high water usage in a climate noted for its short supply of this essential source. But according to McVay, sustainability was a high priority, and the irrigation issue could be solved by recycling rainwater and by using filtered grey water. This proposal appeared to be somewhat generic in that the features presented were exactly what one might anticipate in a large public plaza. Although this team’s plan was a straightforward approach, the addition of numerous structures to the site would have suggested some long-term planning. Images courtesy Otak (click to enlarge) ÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ ÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ Woods Bagot / Surface Design

Image courtesy Surface Design

Navigating through this scheme could only be characterized as adventure. To attract a younger crowd, a large shed (“The Hanger”) as dominating site feature was placed on the original Pepper Street site, as a performance and exhibition area and also containing sports facilities for below-grade soccer, etc.—a facility that any YMCA could only dream about. A series of winding pathways and “Hydro Rooms” as connectors were the primary landscape features, designed to lead people from the perimeter to their interior destinations. Due to the complexity and significant new structures to be added to the site, this proposal undoubtedly had to be realized in phases. Images courtesy Surface Design (click to enlarge) ÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ

The Winning Entry Colwell Shelor / West 8 / Weddle Gilmore

Image courtesy Colwell Shelor (click to enlarge) The winning design’s main feature, “Wind Dancer,” is a sculptural iconic element, which can accommodate festivals, performances and forms of recreation. As a central iconic structure, it is intended, much as Millennium Park in Chicago, to visually attract people to the center of the site. Thus, the focus of the landscape plan, replete with generous plantings of trees for shade, is to draw people to the center of the site. Then there are those gathering places within the site—plazas within the plaza—such as Neon Plaza and the Beer Garden. This approach is very simple and direct with no overreach, and with the iconic feature says, ‘we are the City Center.’ Because of its simplicity, there is little doubt that the design can be accomplished in a single phase. Aside from those important forums with the public, Principal Michele Shelor mentioned that bringing West 8 onto the team was essential in opening up the discussion to some new ideas, which hadn’t been considered initially. Although Shelor did not credit West 8 specifically with the major design features, she did suggest that the input provided by West 8 was a major contribution in tipping the balance in their favor. Below is an excerpt the memo to City Management stating the Selection Committee’s reasoning for choosing Colwell-Shelor/West 8/Weddle Gilmore as the competition winner and as the winner of a design contract to further refine and detail their design.

- The method of public engagement during the design workshops was creative, engaging, and fun for the participants, and public engagement will continue to play a key role in further design.

- Interaction with City officials and staff has been professional, engaging, and thorough.

- The design concept was an exciting, innovative, and iconic reflection of the feedback received during the design workshops.

- The design concept reflects a solid understanding of Mesa’s culture, heritage, and vision for the future.

- The design concept has been well received by the general public as evidenced by the results of surveys completed by attendees of the design reveal event.

- The design concept report is extremely thorough, even including an estimate of maintenance costs and a discussion of alternatives to fund maintenance to be explored with further design.

- City staff has confidence that a positive and effective working relationship will be cultivated with the design team during further design efforts.

Images courtesy Colwell Shelor (click to enlarge)

At this writing, of the $750,000 allotted for this project by the City, the administration of the competition cost $150,000, leaving $600,000 toward construction of the site. As this will only cover 30% of the anticipated budget, the City intends “to use the results of the competition as a basis of the funding campaign.” |

1st Place: Zaha Hadid Architects – night view from river – Render by Negativ

Arriving to board a ferry boat or cruise ship used to be a rather mundane experience. If you had luggage, you might be able to drop it off upon boarding, assuming that the boarding operation was sophisticated enough. In any case, the arrival experience was nothing to look forward to. I recall boarding the SS United States for a trip to Europe in the late 1950s. Arriving at the pier in New York, the only thought any traveler had was to board that ocean liner as soon as possible, find one’s cabin, and start exploring. If you were in New York City and arriving early, a nearby restaurant or cafe would be your best bet while passing time before boarding. Read more… Young Architects in Competitions When Competitions and a New Generation of Ideas Elevate Architectural Quality

by Jean-Pierre Chupin and G. Stanley Collyer

published by Potential Architecture Books, Montreal, Canada 2020

271 illustrations in color and black & white

Available in PDF and eBook formats

ISBN 9781988962047

Wwhat do the Vietnam Memorial, the St. Louis Arch, and the Sydney Opera House have in common? These world renowned landmarks were all designed by architects under the age of 40, and in each case they were selected through open competitions. At their best, design competitions can provide a singular opportunity for young and unknown architects to make their mark on the built environment and launch productive, fruitful careers. But what happens when design competitions are engineered to favor the established and experienced practitioners from the very outset? This comprehensive new book written by Jean-Pierre Chupin (Canadian Competitions Catalogue) and Stanley Collyer (COMPETITIONS) highlights for the crucial role competitions have played in fostering the careers of young architects, and makes an argument against the trend of invited competitions and RFQs. The authors take an in-depth look at past competitions won by young architects and planners, and survey the state of competitions through the world on a region by region basis. The end result is a compelling argument for an inclusive approach to conducting international design competitions. Download Young Architects in Competitions for free at the following link: https://crc.umontreal.ca/en/publications-libre-acces/

Helsinki Central Library, by ALA Architects (2012-2018)

The world has experienced a limited number of open competitions over the past three decades, but even with diminishing numbers, some stand out among projects in their categories that can’t be ignored for the high quality and degree of creativity they revealed. Included among those are several invited competitions that were extraordinary in their efforts to explore new avenues of institutional and museum design. Some might ask why the Vietnam Memorial is not mentioned here. Only included in our list are competitions that were covered by us, beginning in 1990 with COMPETITIONS magazine to the present day. As for what category a project under construction (Science Island), might belong to or fundraising still in progress (San Jose’s Urban Confluence or the Cold War Memorial competition, Wisconsin), we would classify the former as “built” and wait and see what happens with the latter—keeping our fingers crossed for a positive outcome. Read More…

2023 Teaching and Innovation Farm Lab Graduate Student Honor Award by USC (aerial view)

Architecture at Zero competitions, which focus on the theme, Design Competition for Decarbonization, Equity and Resilience in California, have been supported by numerous California utilities such as Southern California Edison, PG&E, SoCAl Gas, etc., who have recognized the need for better climate solutions in that state as well as globally. Until recently, most of these competitions were based on an ideas only format, with few expectations that any of the winning designs would actually be realized. The anticipated realization of the 2022 and 2023 competitions suggests that some clients are taking these ideas seriously enough to go ahead with realization. Read more…

RUR model perspective – ©RUR

New Kaohsiung Port and Cruise Terminal, Taiwan (2011-2020)

Reiser+Umemoto RUR Architecture PC/ Jesse Reiser – U.S.A.

with

Fei & Cheng Associates/Philip T.C. Fei – R.O.C. (Tendener)

This was probably the last international open competition result that was built in Taiwan. A later competition for the Keelung Harbor Service Building Competition, won by Neil Denari of the U.S., the result of a shortlisting procedure, was not built. The fact that the project by RUR was eventually completed—the result of the RUR/Fei & Cheng’s winning entry there—certainly goes back to the collaborative role of those to firms in winning the 2008 Taipei Pop Music Center competition, a collaboration that should not be underestimated in setting the stage for this competition Read more…

Winning entry ©Herzog de Meuron

In visiting any museum, one might wonder what important works of art are out of view in storage, possibly not considered high profile enough to see the light of day? In Korea, an answer to this question is in the making. It can come as no surprise that museums are running out of storage space. This is not just the case with long established “western” museums, but elsewhere throughout the world as well. In Seoul, South Korea, such an issue has been addressed by planning for a new kind of storage facility, the Seouipul Open Storage Museum. The new institution will house artworks and artifacts of three major museums in Seoul: the Seoul Museum of Modern Art, the Seoul Museum of History, and the Seoul Museum of Craft Art.

Read more… |