by William Morgan

The goal of the Add-on ’13 competition was to “seek design proposals for a freestanding, affordable, accessory dwelling unit on outer Cape Cod.” Specifically, the town of Wellfleet, Massachusetts has a bylaw that allows a second living unit–and even up to three extra units–on the lot of an existing home. At the moment, the fishing and resort village has a dozen such accessory dwellings. But the nobler aim of the Add-on competition was to “consider the role of affordable housing” in a non-urban context and to “re-envision the relationship between architecture, infrastructure, resources and the land.” Despite the seeming modesty of the program–800 square-foot, single bedroom units, to cost less than $150,000, Add-on ’13 was a significant contest.

Wellfleet is in the heart of the Outer Cape, the narrow spit of sand that runs to Provincetown from Orleans. The land supports little more than tourism (the Pilgrims, first landed here, but moved on to Plymouth, citing a lack of forests and water). Yet, the area has long appealed to artists and writers, and in the 20th century the area around Wellfleet supported colonies of architects from Boston and elsewhere. Vacationers such as Serge Chermayeff, Marcel Breuer, György Kepes, Florence Knoll, and like-minded designer friends came here. The mid-century modern houses that many of these Cambridge émigrés built are the focus of the work of the Cape Cod Modern House Trust, the organizers of the competition.

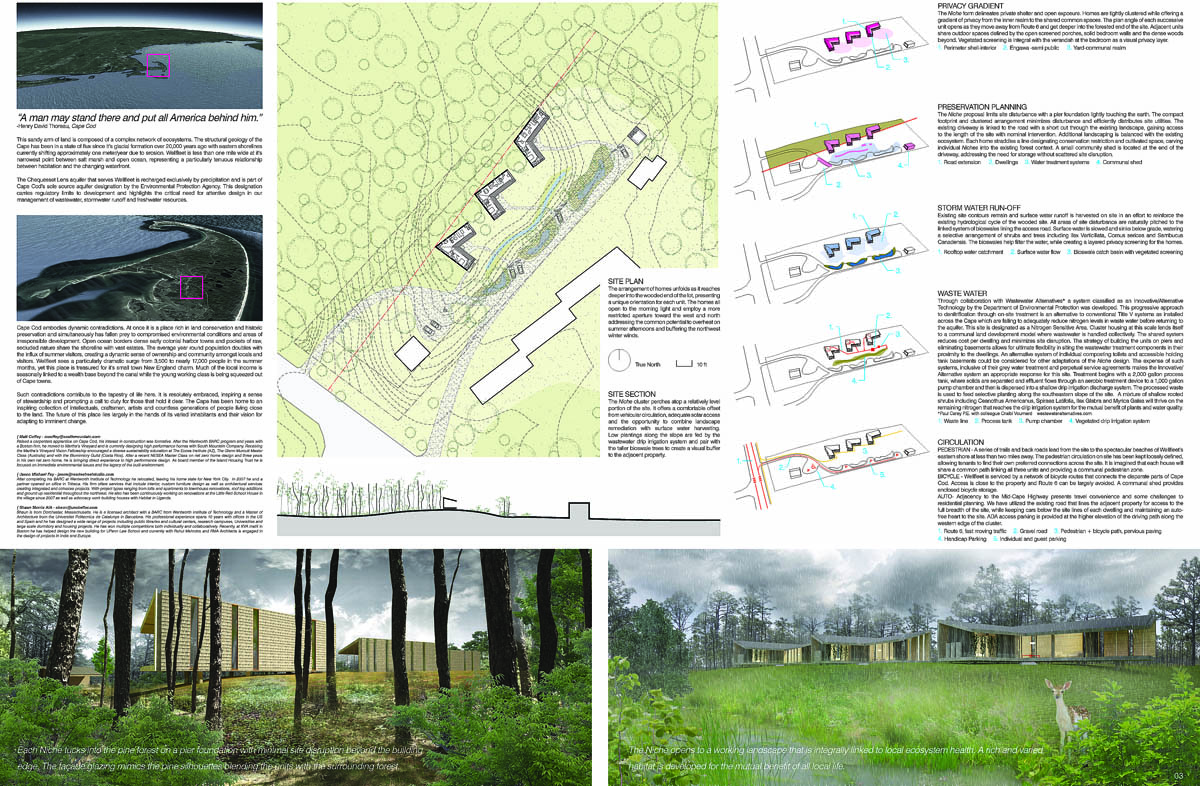

While the Cape Cod National Seashore ostensibly protects much of the Outer Cape, the ecosystem is fragile. The very popularity of Cape Cod as a summer destination has threatened the quality of life that beckons people here. The suburban pattern of one house per building lot has been the rule, resulting in a threatened aquifer, not to mention the scarcity of affordable housing. A single house idea cannot solve all of these problems, but the initial call to submit “innovative designs” for an accessory dwelling unit brought a remarkable response. The contest was open to “designers, architects, builders, and students” in the United States, and over a hundred designs were submitted. Wellfleet offered an empty lot for the competition site.

This is the kind of contest that established firms have neither the time nor the inclination to enter. So, it is no surprise that many of the entrants are young and unknown, which made for an exciting competition. Also, the winning design will be built and perhaps replicated. Nevertheless, the cachet of the Cape and respect for CCMHT founder Peter McMahon led what finalist Michael Shanks called “a terrific jury and very interdisciplinary.” The jury included historian Kenneth Frampton, MIT professor William O’Brien, Jr, Pratt professor Duks Koschitz, Tulay Atak from Cooper Union, Mary-Ann Agresti and Anne Tate from RISD, and filmmaker Malachi Connolly, along with Gary Sorkin of the Wellfleet Housing Authority.

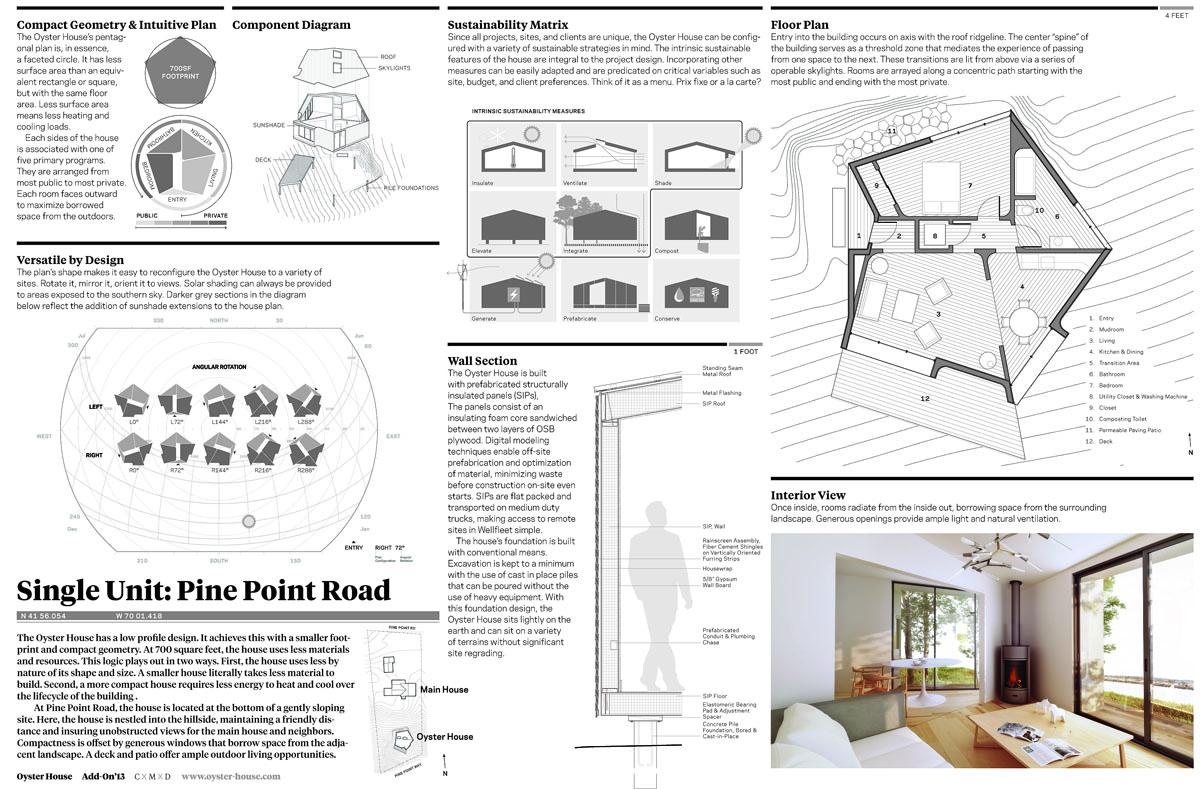

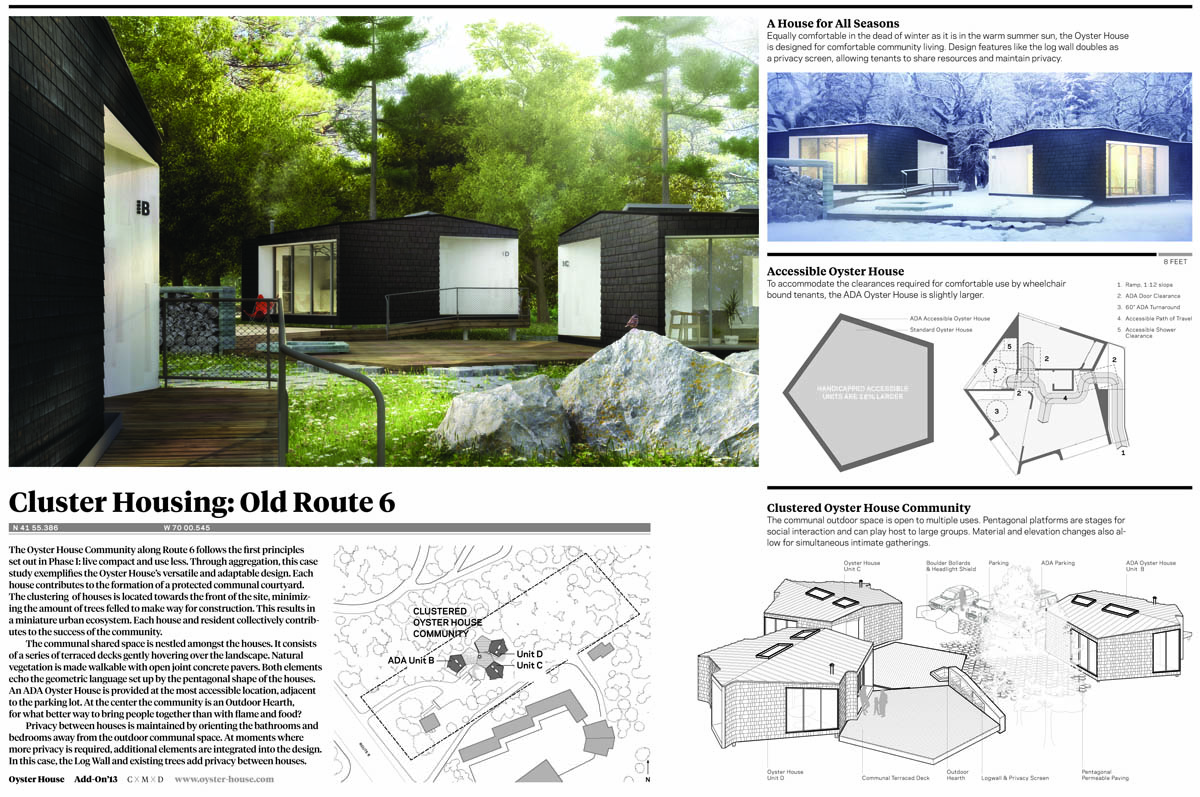

One of the finalists, Eric Rothfeder, said that “as a young architect” he found the two-stage structure of the competition very beneficial, as the first stage did not require a fully developed scheme. This, Rothfeder feels, “allowed more designers to enter the competition and present their ideas, while the second stage yielded schemes that were more responsive to the needs of the community by incorporating their input.” Christopher Lee of the winning team of CxMxD echoed that, noting, “The fact that the competition asked for solutions to address larger issues of housing in Wellfleet made the project more meaningful … We challenged ourselves by asking whether we could create a new and affordable housing type that respected the history of architectural experimentation in Cape Cod.” Lee also singled out the review by Wellfleet residents. “We wanted to make the sure the work was accessible.”

Six finalists were asked to develop their designs, as well as propose construction strategies for local needs. They were invited to spend a week in two of the houses restored by the Trust. Again, Rothfeder wrote, ” … a great ‘prize’ (I think all the finalists were able to take a nice vacation on Cape Cod) but it was also an opportunity to visit the competition site, tour the other modernist houses … and to better understand the affordable housing crisis that prompted the competition.” The finalists met with local planning boards and citizens (the public was encouraged to vote on the designs), while Add-on ’13 invited another thirteen designers to display their proposals. All were exhibited, first in Wellfleet and then at the Boston Society of Architects. It was hoped that such publicity might encourage other Cape Cod towns to pass accessory dwelling laws similar to Wellfleet’s. “At the very least,” competition leader McMahon says, the competition “started a conversation, which suggested all kinds of possibilities.”

The entrants offered up a wide range of affordable housing solutions, from synthetic landscapes to vernacular houses, and variously addressed terms of land use, changing demographics, and community needs, not to mention environmental concerns. The proposals were evaluated on aesthetics, livability, buildability, site strategy, and the social possibilities of clustering.

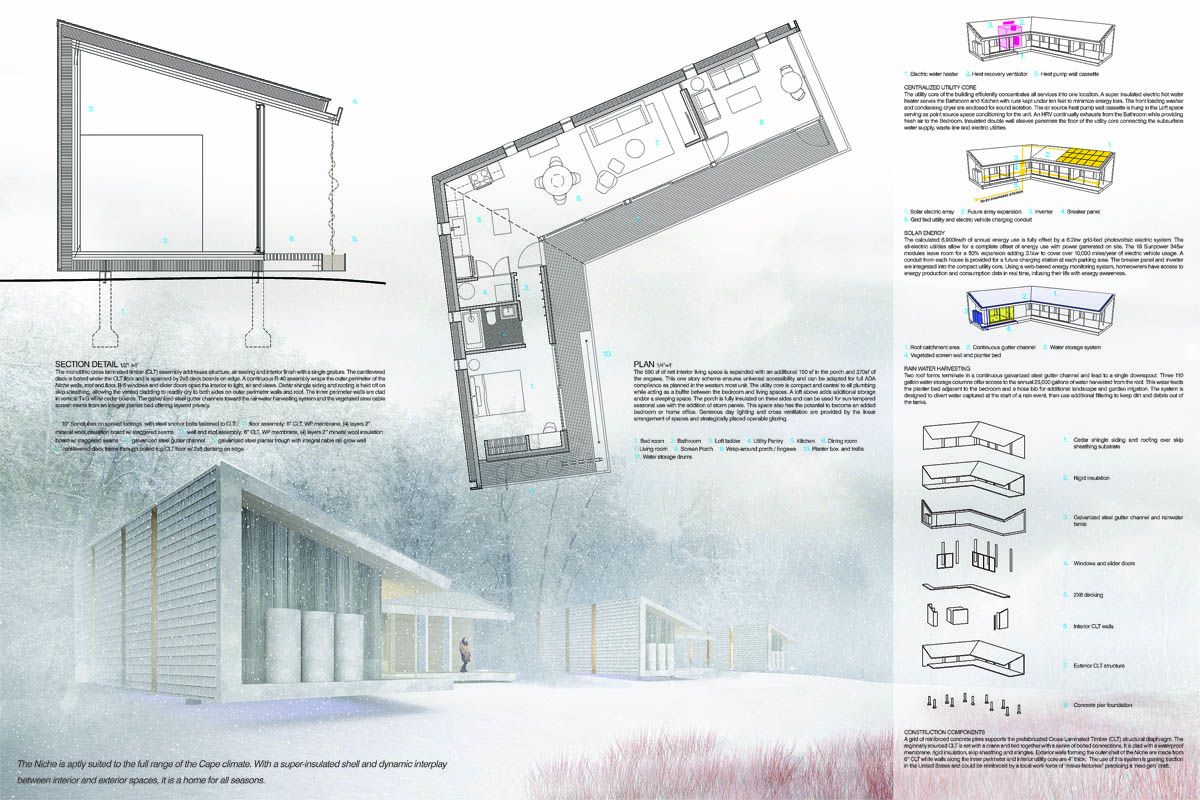

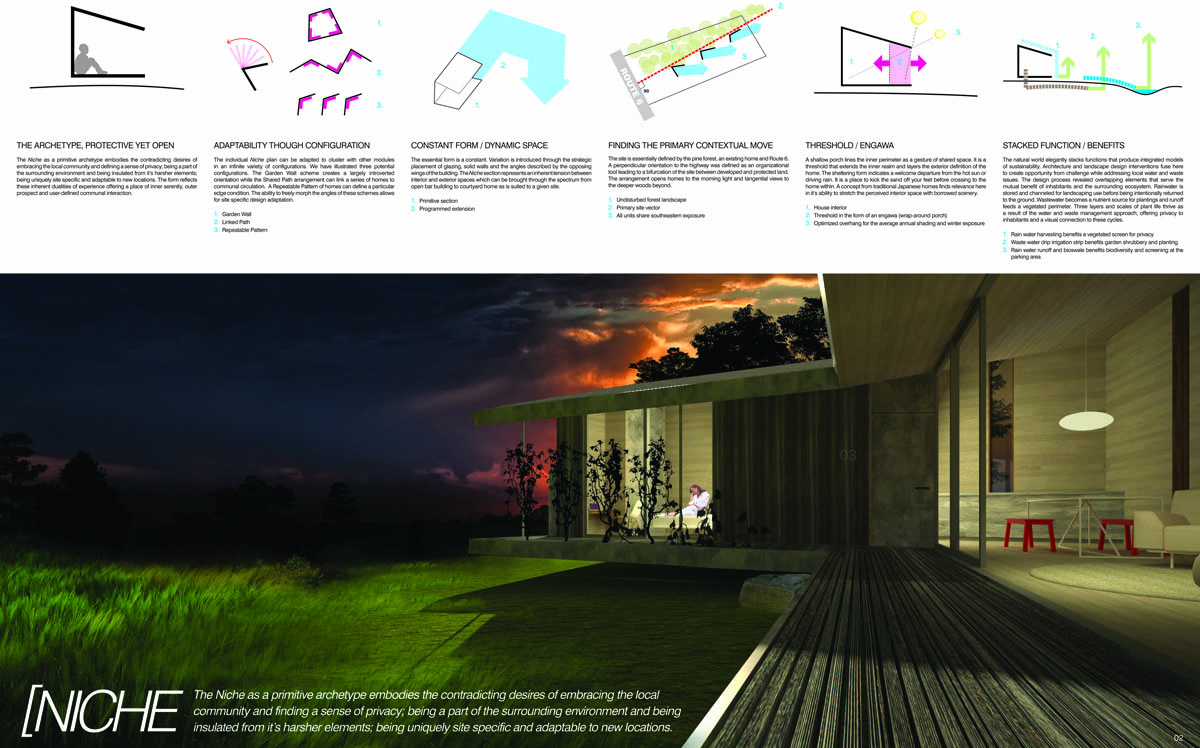

“Niche” by Unshelter was one of the most traditionally modern designs; its L-shaped plan has outer protective walls sheathed in the ubiquitous cedar shingles of the Cape. The other walls are glazed, set behind screens and beneath broad overhanging roofs providing both privacy and openness—500 square feet of living space is augmented by two sizeable verandahs. The team of Shaun Morris, Jason Fay, and Cape Cod native Matt Coffey used Cross Laminated Timber interior walls to act as structural bearing members; CLT can be shipped as pre-fabricated modules. Regardless of the outcome, team leader Morris recalled that he “particularly enjoyed the close, collegial relationship with the competition organizers and the chance to discuss the project with the residents of Wellfleet at the town-hall style meeting … we weren’t just working far away in a design bubble but were personally involved.”

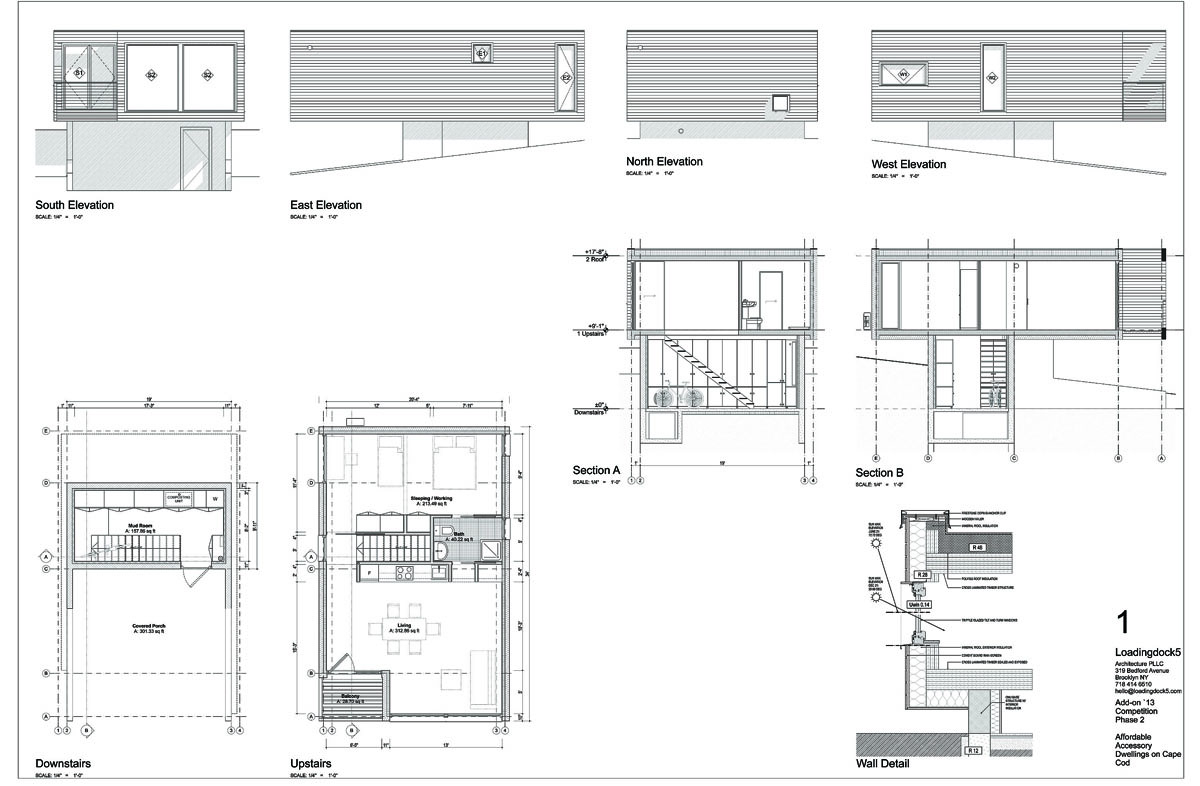

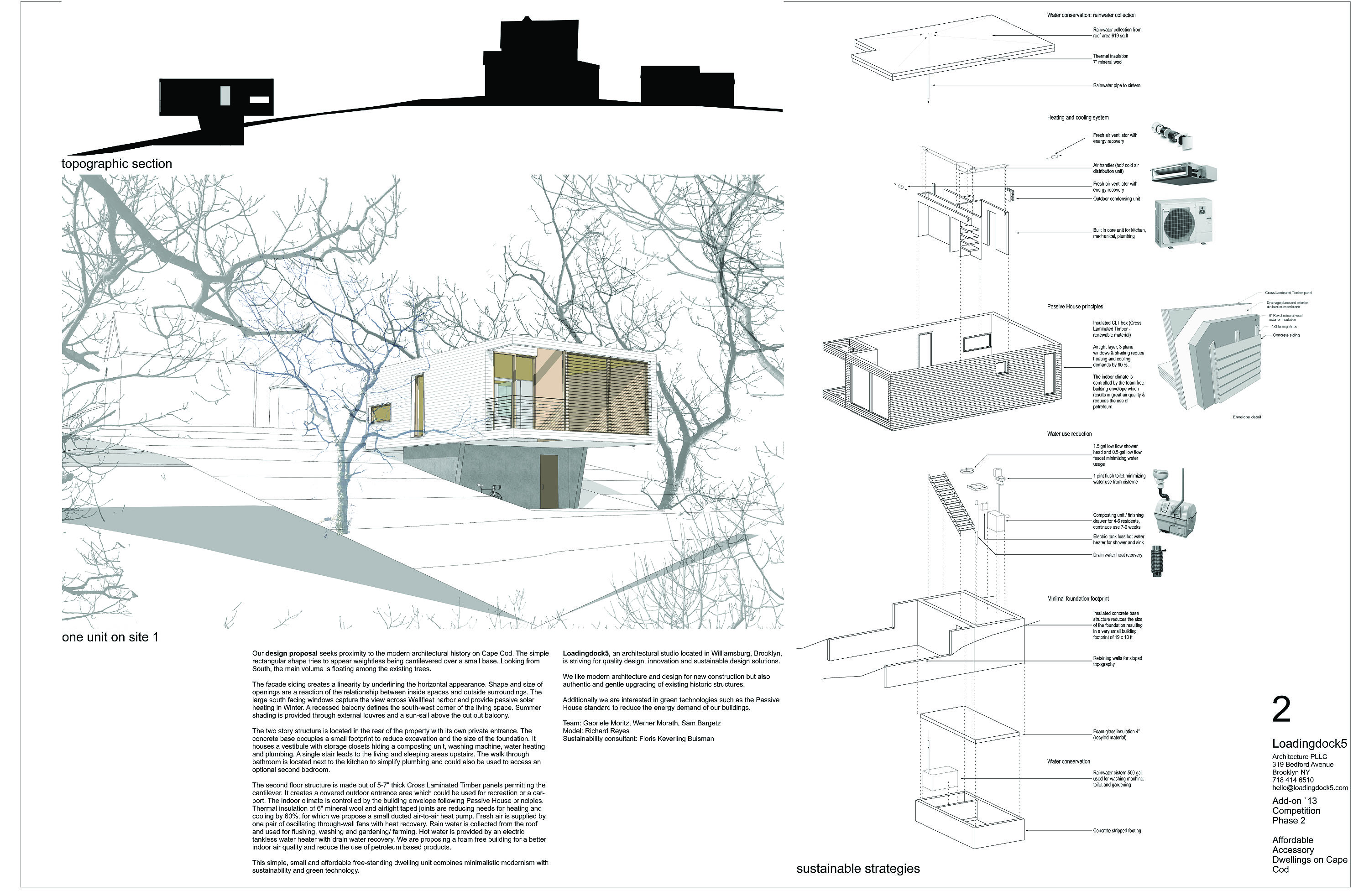

Far more ambitious–or perhaps less contextual–is the Cantilever, the design by two Austrians, Werner Morath and Sam Bergentz, who practice in Brooklyn under the firm name of loadingdock5. Their Add-on house (“minimalistic modernism with sustainability and green technology”) is a rectangular cube cantilevered over a smaller concrete vestibule-base, which has storage closets, a compositing unit, laundry, and utilities. The living-sleeping second story is built of CLT; a wall of glass on the south front provides a European flavor as well as view over Wellfleet harbor.

Passive house principles, as well as rainwater collection for flushing, washing, and gardening, are typical of the thoughtfully green outlook of most of the participants.

“Cantilever” presentation boards by loadingdock5 (click to enlarge)

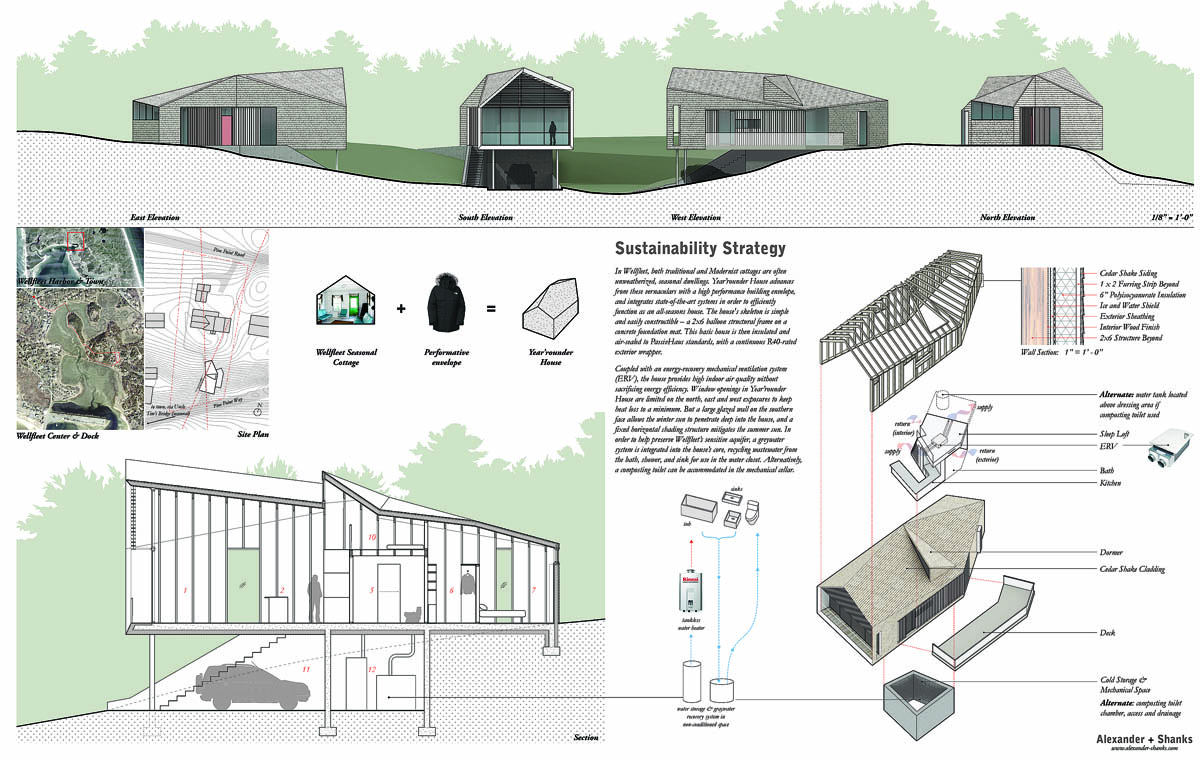

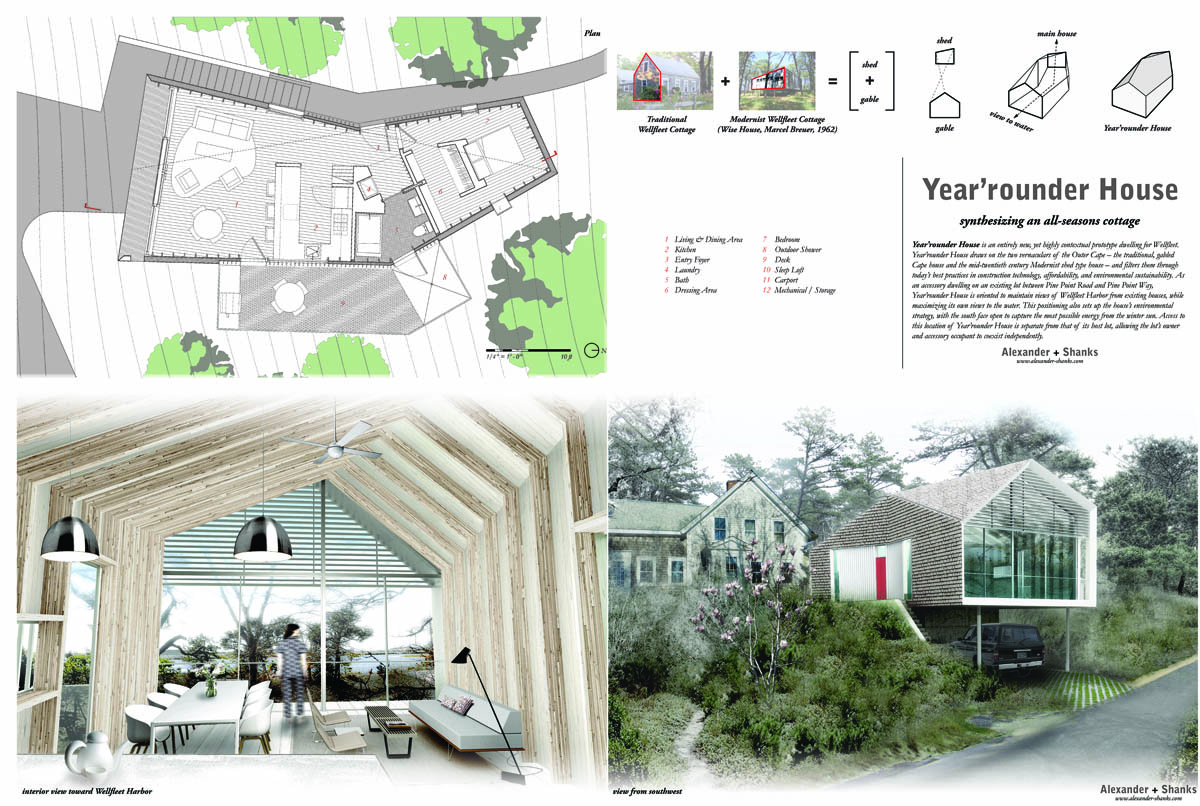

Alexander + Shanks, also from Brooklyn, offered another cantilevered and shingled shelter, called Year’rounder House. They drew upon the “two vernaculars of the Outer Cape–the traditional, gabled house and the mid-twentieth century Modernist shed type house–and filtering them through today’s best practices in construction technology, affordability, and environmental sustainability.” Right on the street in front of the Greek Cape, Year’rounder House projects over a carport. The glass gable front is actually trapezoidal, hinting at the boat-like twisting of the frame/hull. David Shanks and Michael Alexander depict their house as part of a cluster, a prospect that would no doubt lessen the impact of somewhat incongruous shapes for more conservative local palates.

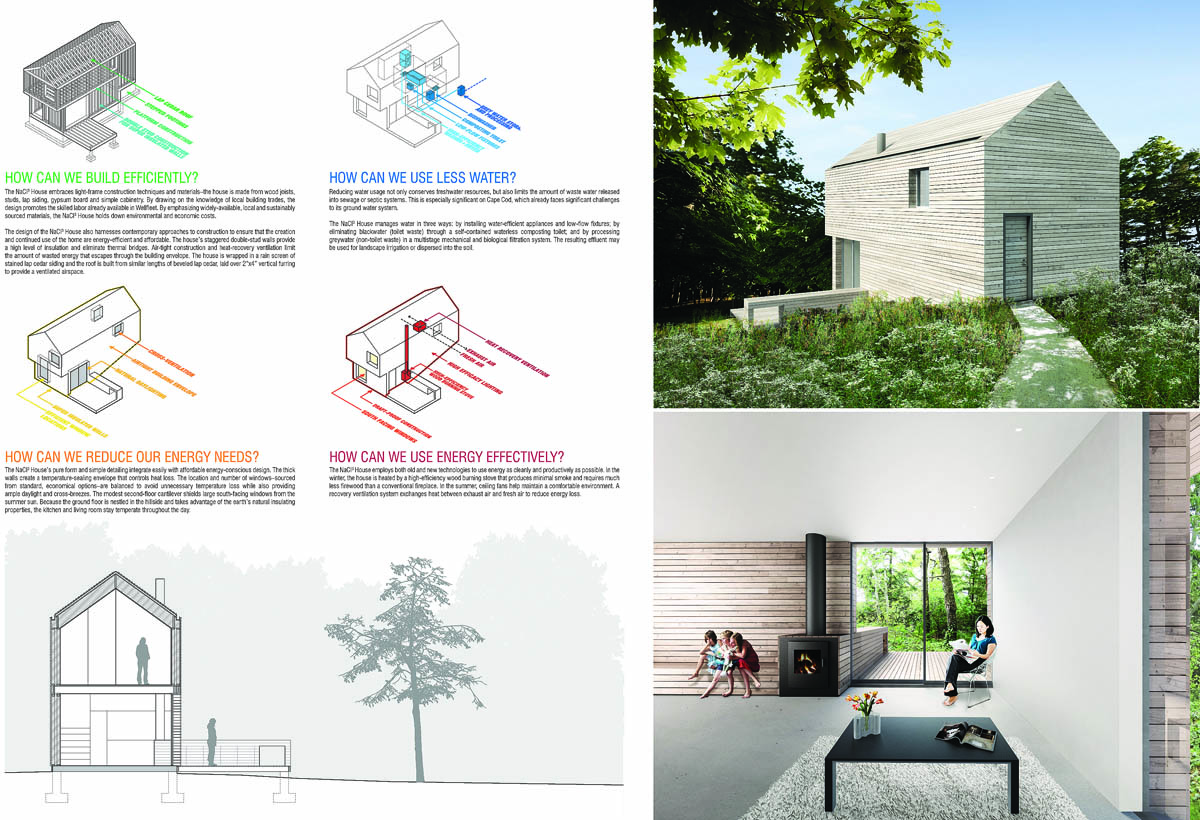

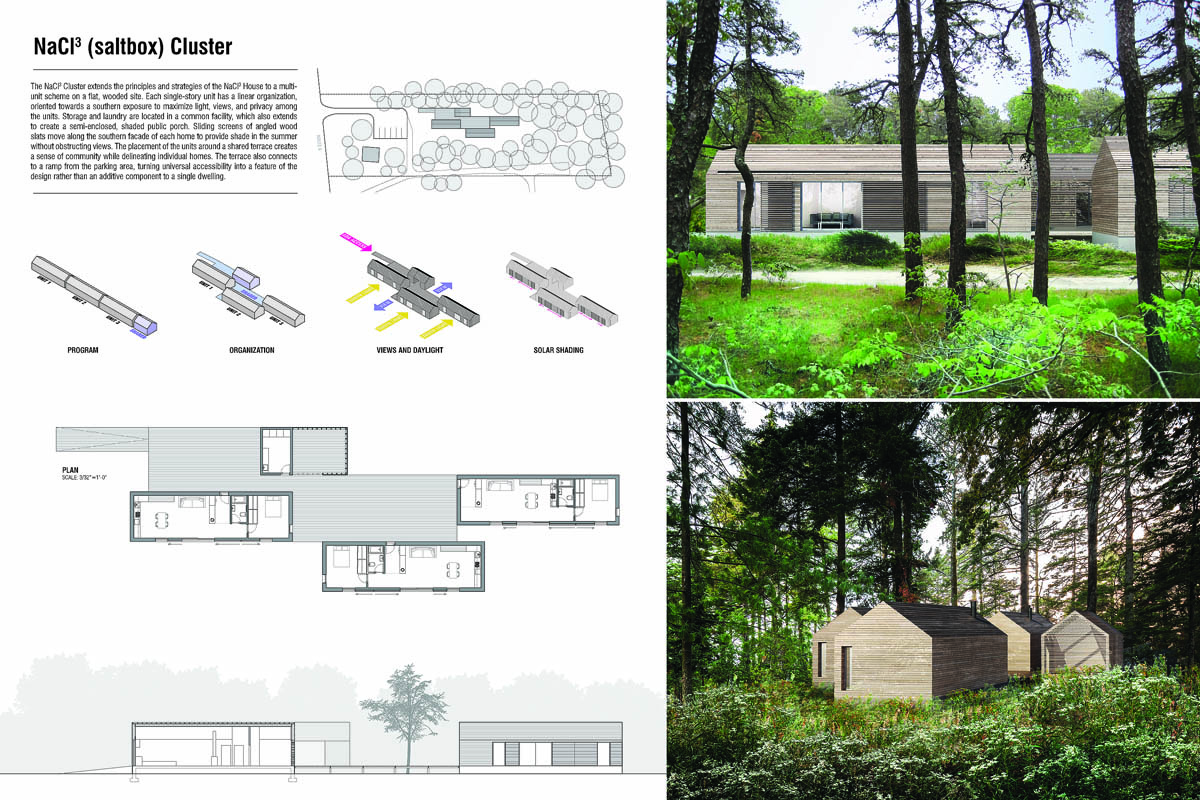

Several of these designs are to be replicated; several rely on the cantilever idea, no doubt due to the slope on the Wellfleet specific site. Eric Rothfelder’s NaC13 also leans over the hill, with its gable end to the road. The house’s shape “recalls the peaked roof and proportions of classic Cape Cods, yet its form is abstract, monolithic and sculptural.” The outline is simple (which contributes to its energy efficiency) and its weathered shingled wrapping would make it easily reproducible. In many ways, NaC13 seems closest in spirit to the Wellfleet vernacular

“NaC13” presentation boards by Eric Rothfelder (click to enlarge)

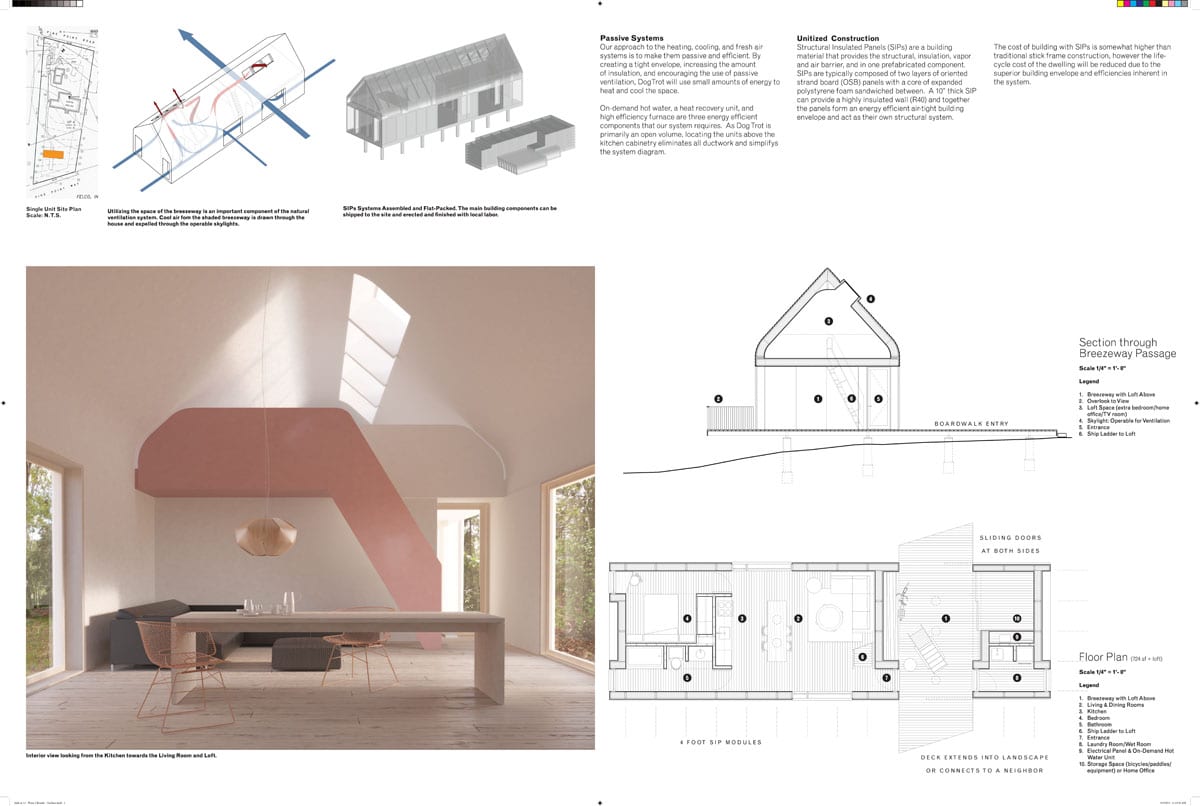

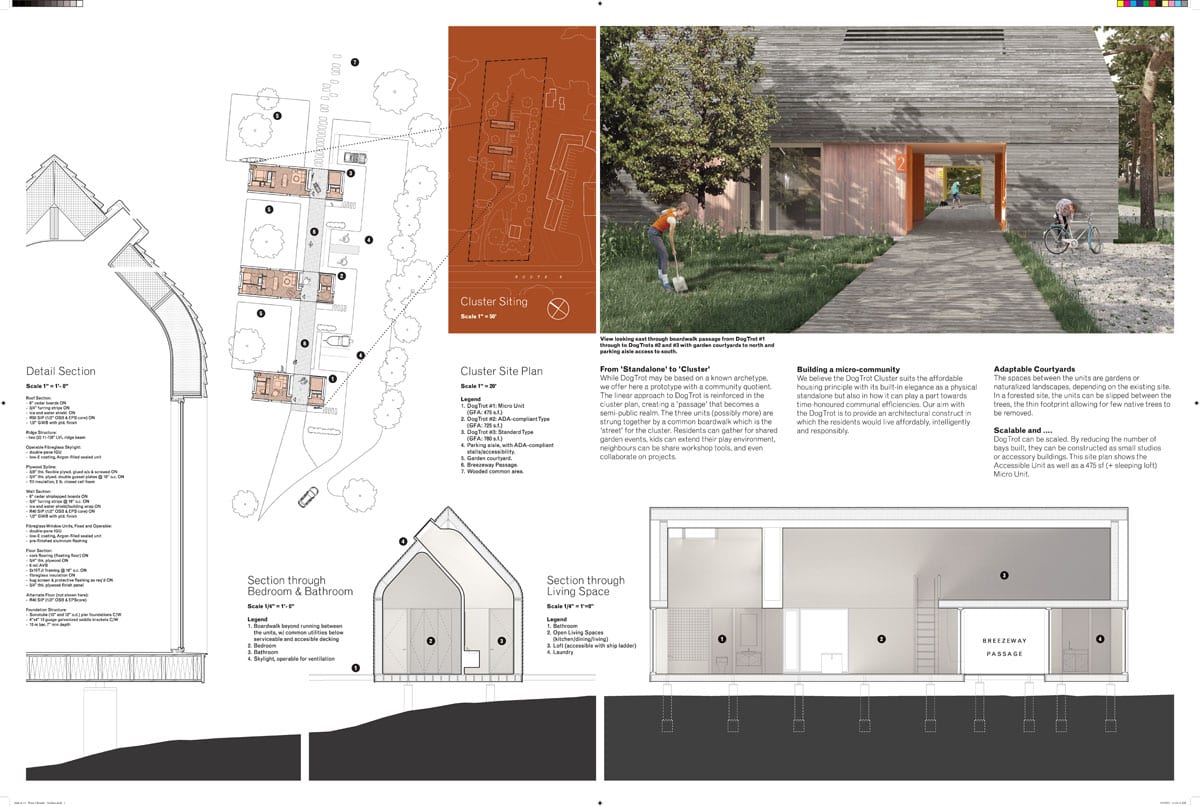

DogTrot by WCA, the Toronto-based firm of Donald Chong and Betsey and Shane Williamson, is also a straightforward rectangular gable barn shape, but with two sides open and a long skylight in the roof. Simplicity often works best, although the prefabricated Structural Insulated Panel facades seen in the renderings might put off some natives. DogTrot is quite sophisticated in terms of passive energy systems. An actual open space, or dogtrot, creates a passage through the house.

“DogTrot” presentation boards by Donald Chong and Betsey & Shane Williamson (click to enlarge)

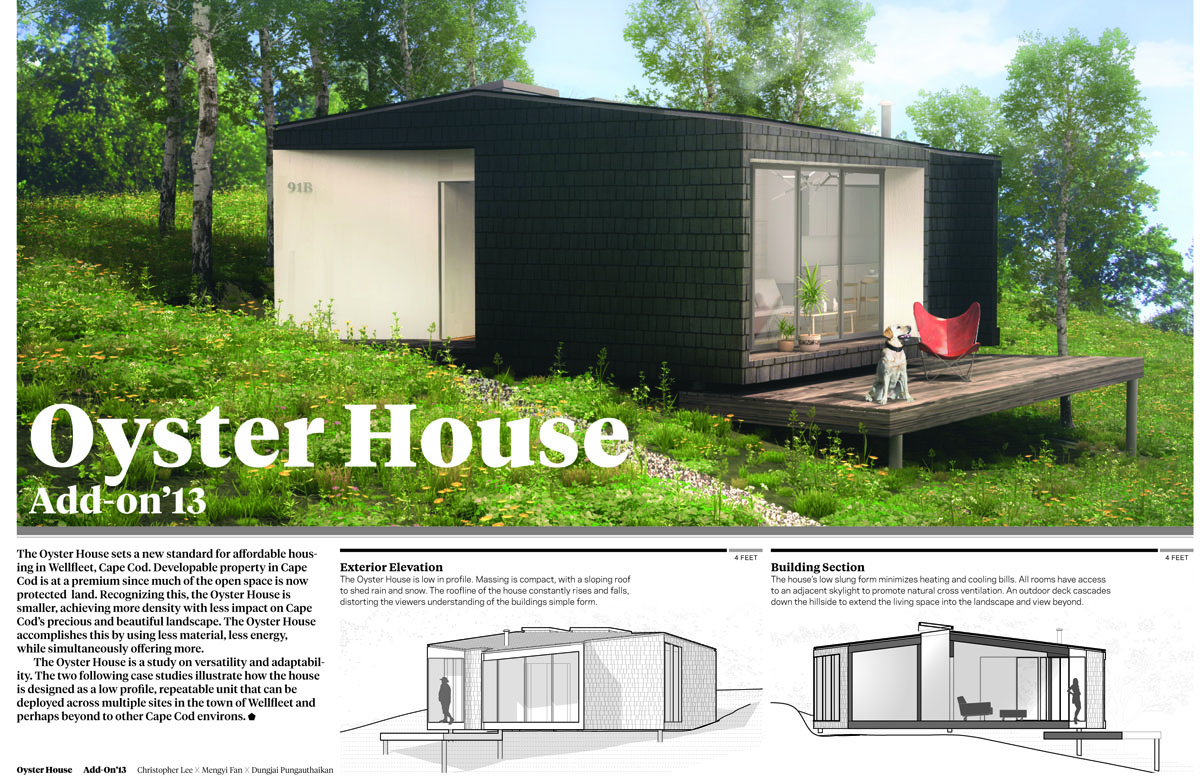

In a contrast to such basic building-block forms, the winning design is characterized by an unusual plan. Oyster House, by CxMxD, is the collaboration of Christopher Lee, Mengyi Fan, and Dungjai Pungauthaikan (two of whom work full-time for SHoP Architects, Lee having been the lead designer for the Barclays Center in Brooklyn). The faceted circle/pentagonal plan offers more floor space than a rectangle. Each room in the ingenious layout faces outward, while the plan makes it easy to “reconfigure Oyster House to a variety of sites” and client preferences. As for architectural expression, the Oyster House may not have been a show-stopper at first glance. But there can be no doubt that the jury was thinking beyond outward appearances to the role the house could play in Wellfleet and across the Cape. They should be commended for not turning this into a simple beauty contest.

“Oyster House” presentation boards by CxMxD (click to enlarge)

Don Spring, the denizen of an older bow-roof cottage and a commentator on everything Cape Cod, declared that the “judges must have been a bunch of Cambridge, trust funder, MIT/Harvard moon bat professors.” Yet given the relative youth and hence more avant-garde flavor of many of the entrants, as well as the reception by the citizens of Wellfleet itself, the quality of the Add-on ’13 competition was incredibly high. As one of the competition organizers (along with McMahon and Koschitz), Tulay Atak recalls that her “favorite part of the entire process was the event at the Wellfleet Library where the finalists presented their designs to the town and the competition committee.” Rather than designing for the moon bat professors, “the designers had the chance to see who they were designing for and hear their questions and concerns.”

Although the town is preparing an RFQ/RFP to provide “a multi-unit accessory dwelling unit cluster,” the winner(s) of this competition will probably not be consideration for this project. Even so, winner Christopher Lee remains acutely aware that competitions “will always be high risk, for little reward.” Yet, Tulay Atak provides the best summation of Add-on 13: “The quality of the entries showed that the competition was a worthwhile cause and that contemporary design can still contribute to the question of affordable housing. For me, the entire event made it apparent that design can play a role in the public realm.” According to Peter McMahon, “The good news is that the Housing Authority discovered they can use the Accessory Dwelling bylaw to build multiple units on single family lots they acquire, which could be a game changer for them.”

Competition Jury

• Mary Anne Agresti, Chair, Boston Society of Architects, Cape and Islands Chapter Principal, The Design Initiative, Hyannis MA

• Tulay Atak, Visiting Associate Professor, Pratt Institute